Let the Chinese cars in

There's a way to do it so that the benefits outweigh the costs.

It might come as a surprise that I’m writing a post advocating that the United States allow Chinese cars to be sold here. First of all, it’s well known that I view China as both an economic and a geopolitical threat to the U.S.; I’ve repeatedly praised the U.S. export controls that stop China from buying American chips and chipmaking equipment. I’ve urged Europe to use trade barriers to make sure that sudden waves of subsidized Chinese goods don’t forcibly deindustrialize its economy. And when it comes to tariffs, I’ve argued that targeted tariffs on final consumption goods (e.g. cars) are less economically harmful and more effective than other kinds of tariffs.

Given all of that, you wouldn’t think I’d write a post saying “America should buy Chinese cars after all.” Yet here we are.

This post was precipitated by Canada’s decision to almost completely eliminate tariffs on Chinese-made EVs, as part of a trade deal:

Under the arrangement, Canada will slash its tariff, currently 100%, to 6.1%, and allow Chinese electric vehicle imports of 49,000 units, rising to 70,000 over five years. Half of the annual quota is slotted for EVs costing less than CA$35,000. Beijing will also make a “considerable investment” in Canada’s auto sector over the next three years, Mr. Carney said. In return, China will slash its tariff on canola seed, one of Canada’s most important agricultural exports, from roughly 84 percent to about 15 percent.

This is not part of a general free trade deal between China and Canada — it’s a targeted agreement. But politically, it’s a big break between Canada and the U.S. Back in 2024, when Biden imposed 100% tariffs on Chinese EVs, Canada followed suit — no doubt worried about losing its crucial American markets and displeasing its indispensable ally.

Now, with Trump constantly threatening steep tariffs on Canada, relations between the two countries generally deteriorating, and U.S. auto investment in China in a long secular decline, Canada’s leaders don’t see as much downside from breaking with the U.S. policy line. (The move might even serve as a signal that if Trump starts threatening Canada the way he’s been threatening Greenland, Canada could geopolitically reorient toward China for protection.)

This is another illustration of how Trump’s bullying tactics often produce unintended consequences. But in fact, Canada’s move is one the U.S. should copy — with some added provisions. Currently, the U.S. has a total tariff of 125% on Chinese-made EVs, along with a ban on cars that are connected to Chinese software ecosystems.

The U.S. should follow Canada’s lead on EV tariffs, slashing them to a very low level while initially limiting the number of annual imports. While Canada’s deal involved only vague promises of Chinese investment in the Canadian auto industry, the U.S. should require far more firm commitments, along with strong incentives for local sourcing of components like batteries and motors. And the dangers of espionage and sabotage can probably be minimized through additional measures.

There are a number of reasons that this would be in America’s own self-interest.

America needs Chinese EVs because it needs more EVs

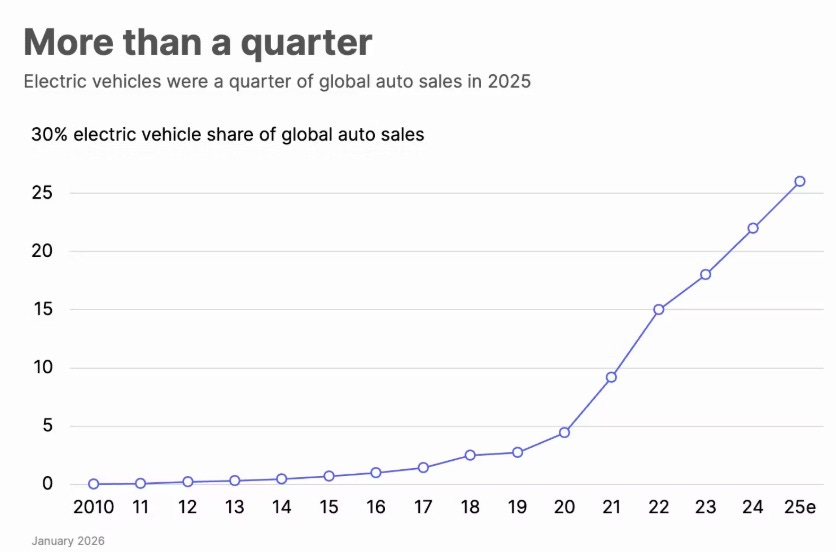

The main reason to let in Chinese EVs is that the United States needs to embrace EVs in general. The world as a whole is doing this:

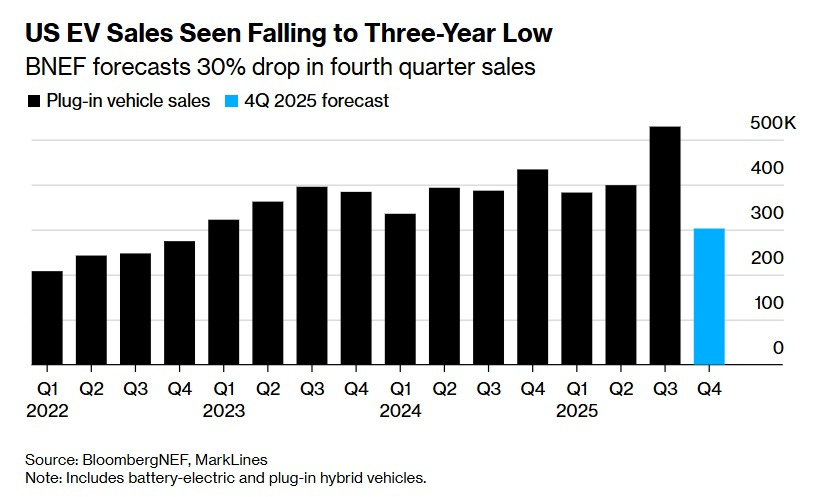

But in the U.S., the transition to EVs has stalled:

Part of this is due to Trump ending subsidies for EVs. Part of it is Tesla’s unpopularity; the company still dominates U.S. EV sales, but its image has suffered enormously as a result of Elon Musk’s right-wing politics and erratic behavior. But on top of all that, the traditional big U.S. automakers — Ford, General Motors, and Stellantis — have simply been unable or unwilling to compete in the EV space so far:

Ford Motor Co. announced $19.5 billion in charges tied to the retreat from an electric strategy it vowed to go all in on eight years ago…General Motors Co. recently incurred $1.6 billion in charges tied to paring EV production capacity, and flagged more such moves may be in the offing. Stellantis NV has scrapped plans for a fully electric Ram pickup…

For Ford, the eye-popping charges the carmaker expects to record are linked to moves including the cancellation of a planned electric F-Series truck line, shifting production toward gas and hybrid vehicles and repurposing battery plants to produce energy storage systems instead of EVs.

But this is very bad for the U.S. First of all, if the U.S. keeps driving combustion cars while the rest of the world switches to EVs, American automotive technology will be orphaned from the rest of the world. Currently, GM and Ford both make almost a fifth of their revenue from overseas sales; if they only make gasoline cars that the world has no interest in buying, those export markets will be cut off, and the U.S. companies will be confined to their home market. This is known as “Galapagos syndrome”, because it’s as if the U.S. car industry lived on an isolated island.

Second of all, the U.S.’ turn away from EVs will make it a lot harder for the country to develop an indigenous Electric Tech Stack. Batteries and electric motors are the key to lots of future technologies, including all-important military hardware like drones. Currently, the U.S. can’t build many batteries or motors; if this situation continues, American military power will wither.

On top of that, lots of physical technologies — transportation, electronics, robots, and others — are converging on a standardized package of components that includes batteries and electric motors. A country that has no electric supply chain will lose an increasing number of manufacturing industries as more and more devices switch to the Electric Tech Stack. By providing the single biggest source of demand for batteries and electric motors, EVs allow producers of those components to attain large scale, thus driving down costs for a bunch of other manufacturing industries.

In other words, the more Americans learn to like EVs, the more EVs they’ll buy. And if some of those EVs are made in America, it’ll create local demand for American-made batteries and electric motors — especially with joint-venture requirements and local content incentives. That, in turn, will help the U.S. become a producer of batteries, motors, and other electric technologies, which will help the country stay competitive in manufacturing across the board.

Some Americans would buy Chinese EVs if they could

Obviously, this won’t work if Americans shun EVs from BYD and Xiaomi, the way they’ve started shunning EVs from Ford and GM. But there are reasons to think that won’t happen. First of all, Chinese EVs are very cheap, partly because of subsidies, but partly because China has essentially the entire EV supply-chain in-country, and has attained massive scale. A lot of Americans would love a cheap nice car.

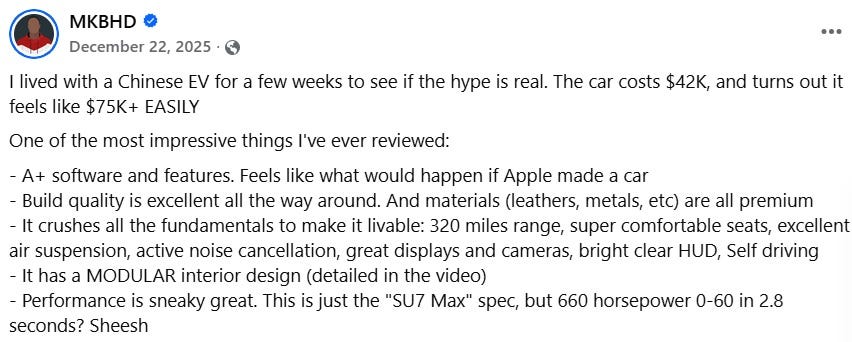

And these Chinese EVs aren’t just cheap; they are nice. China’s EV industry is viciously competitive (partly because those government subsidies force it to be viciously competitive), so China’s automakers compete on high quality as well as on low price. There has been a lot of reporting over the last three years on how high-quality Chinese EVs are now; here’s a representative review from Facebook:

In addition to futuristic design and high manufacturing quality, Chinese EV makers have developed a bunch of innovative technological features — ultra-fast charging, semi-autonomous driving even in cheap models, and so on.

People who try these cheap, high-quality cars often see the light and switch. Mexico slapped 50% tariffs on Chinese EVs, and they’re still making big inroads into local markets.

This doesn’t mean Americans would all stop driving F-150s and RAV4s and start driving BYD Seals and Xiaomi SU7s. Many Americans will keep their gas-guzzlers. But just as with fuel-efficient Japanese compact cars in the 1970s and 1980s, Chinese EVs would become a significant segment of the market.

Even if Detroit didn’t try to compete in that segment, this would have some beneficial effects. More EVs on the road would mean more demand for charging stations, which would help build out the nationwide network of chargers necessary to eliminate “range anxiety” for people who want to use EVs for very long road trips.

And once EVs became popular among middle-class Americans, more Americans would realize all their inherent advantages — much lower maintenance costs, low noise, fast acceleration, low fuel costs, and the fact that you almost never have to visit a charging station (because you charge it at night at your house). That popular realization would boost long-term demand for EVs in America as well.

That technological upgrade alone would be beneficial for Americans. But there would probably be plenty of other benefits as well.

How Chinese EVs would benefit America’s industrial ecosystem

One way Chinese EVs would benefit America is by forcing Detroit to compete. You can read plenty of articles on how GM and Ford have struggled in their initial attempts to switch to EVs. They’re not being lazy; a huge technological shift like this is just inherently very hard. But without competition, U.S. automakers are likely to simply throw in the towel when faced with initial difficulties like this; they can just go back to selling their old gasoline-powered cars, take a financial loss, and just shrug and say it didn’t work.

But with competition from Chinese EVs, it would be much harder for Ford and GM and Stellantis to give up when the going got rough; if they did, it would eventually mean that BYD and Xiaomi would eat into their market share. They would be forced to make the big investments — to hire engineers and designers who know how to make EVs, to do their own innovation in features and technology, to improve their production processes, and so on — and to keep doing this until it worked.

In fact, something like this happened in response to the First China Shock, back in the 2000s. That wave of cheap Chinese-made imports did devastate lots of U.S. manufacturing and hurt lots of workers, but it also forced local manufacturers to increase their innovation and productivity. Bloom et al. (2011) found that although the First China Shock hurt European profits and workers alike, it also increased innovation and productivity among European producers:

We examine the impact of Chinese import competition on patenting, IT, R&D and TFP using a panel of up to half a million firms over 1996-2007 across twelve European countries…Chinese import competition had two effects: first, it led to increases in R&D, patenting, IT and TFP within firms; and second it reallocated employment between firms towards more innovative and technologically advanced firms. These [two] effects were about equal in magnitude, and [together] appear to account for around 15% of European technology upgrading between 2000-2007. Rising Chinese import competition also led to falls in employment, profits, prices and the skill share.

I don’t like seeing U.S. companies get hurt, but the alternative might be far worse — a long slow death as they cling to a comfortable but obsolete technology. Chinese EVs could be just the thing to save Detroit from its own short-termism, the way Japanese compact cars were in the 1980s.

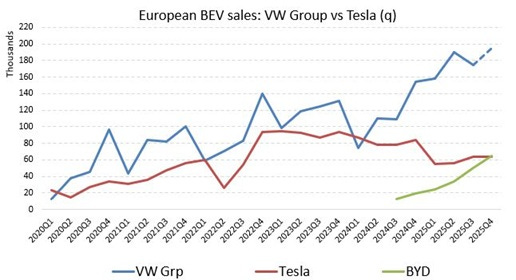

In fact, this might be what’s already happening in Europe. Europe put only modest tariffs on Chinese EVs, and at first their domestic car brands got clobbered. But recently, Volkswagen appears to have gotten its act together and started selling EVs in its home market:

If VW can do it, Ford and GM and Stellantis can do it too.

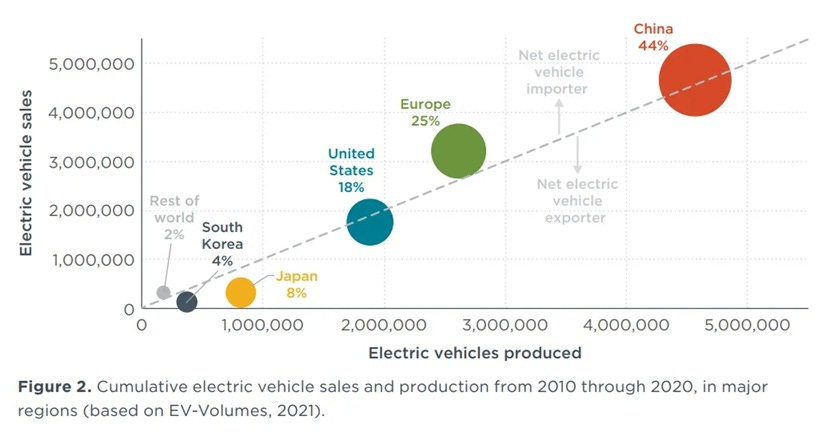

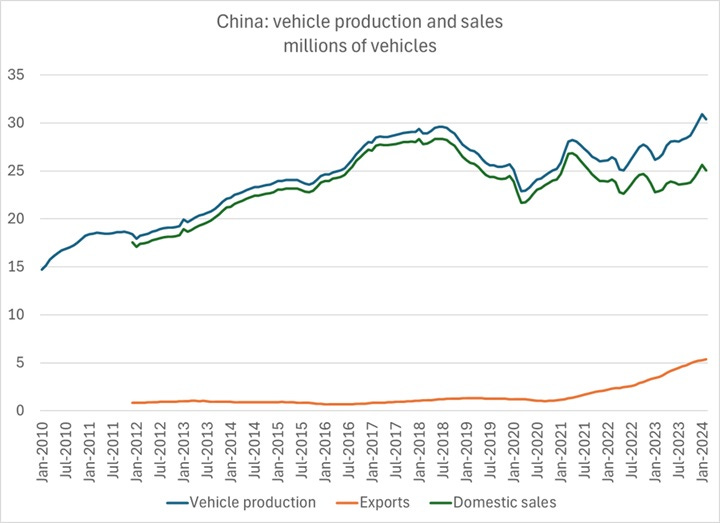

The beneficial effect on the rest of the U.S. industrial ecosystem, though, could be even greater. Remember that because cars are very heavy, they’re expensive to ship; they tend to be made close to where they’re consumed.1 This is what production and consumption looked like in 2010-2020, before the Second China Shock began:

And even once China began paying its companies to export huge numbers of EVs, and became the world’s largest auto exporter in just a few years, most Chinese-made vehicles are sold in China:

Over time, the pattern of global auto production would shift back toward this equilibrium. As U.S. companies leveraged their proximity advantage to cancel out China’s price advantages, BYD and Xiaomi and the other big Chinese automakers would start building factories in America. If not, a little bit of tariff could help them along once they’re already in the U.S. market.

This is exactly what actually did happen with Japanese automakers. After a trade kerfuffle in the late 80s and early 90s, Japanese automakers went all-in on building factories in America. Now, Japanese carmakers employ over 400,000 Americans, and Japanese carmakers have helped teach Americans their tricks for highly efficient manufacturing.

And in fact, Chinese automakers are already building factories all over the world; BYD’s investments are concentrated in Brazil, Thailand, Indonesia, Hungary, Mexico, and Turkey. There’s no reason they couldn’t be in the U.S. as well.

There are plenty of things the U.S. could do in order to speed that transition along. One idea would be joint venture requirements, forcing BYD and Xiaomi to include American companies in their local operations, in order to make sure that EV manufacturing know-how gets transferred from China to America. This is exactly how China built up many of its own manufacturing sectors, and Europe is now considering implementing similar requirements for Chinese factories.

Even more important could be local content incentives. If the U.S. taxed imported components used in Chinese-owned U.S. factories — especially batteries, electric motors, and power electronics — this could force Chinese companies to help build up America’s own capabilities in the Electric Tech Stack. BYD, for example, is vertically integrated, and could easily build batteries in the U.S. (preferably, once again, with a joint venture requirement).

Thus, Chinese companies’ desire to sell electric cars to Americans could end up helping to reindustrialize America. It could create plenty of factory jobs, transfer manufacturing know-how, and create demand to build up the U.S. component ecosystem.

It might seem like “tariff man” Donald Trump would be averse to such a scheme, but in fact he recently proposed something like this himself:

During a speech at the Detroit Economic Club this week, President Donald Trump made it clear that he’s perfectly fine with Chinese automakers setting up shop in the States. With just four words, he effectively welcomed brands like BYD and Xiaomi to compete with Detroit in their own backyard: “Let China come in.”

On one condition, of course: These companies are welcome as long as they build a plant in America and hire Americans to work the factory floor.

This isn’t something I say very often, but Trump is right. Let China build cars for the U.S. market, especially if they build them with U.S. workers, U.S. corporate partners, and U.S.-made components.

The risk: espionage and sabotage

So far, of course, I’ve neglected the big, obvious risk from Chinese EVs: espionage and sabotage. If China makes the electronics and the software for a substantial number of America’s cars, they can presumably track the movements and collect the personal data of lots of Americans. For this reason, Israel has banned Chinese-made cars on its military bases.

Even more worryingly, they might be able to turn off America’s cars at the start of a war, or cause them to start swerving uncontrollably and cause vast numbers of accidents, paralyzing much of the nation and killing untold numbers of Americans. There have already been some accusations of carmakers doing things like this, as cars become more networked and software-dependent. Whether the accusations are true or not, the risk is obvious.

But although I’m not a cybersecurity expert, it seems likely that there are ways to manage these risks without forbidding Chinese companies from selling anything in America. Researchers are working on new techniques to detect and prevent such meddling; my basic recommendation is for a lot more resources to be poured into those efforts. Detecting and countering Chinese espionage and sabotage efforts will be important whether we buy Chinese cars or not, since China already makes so many of our electronic devices.

Ultimately, this will be a lot easier with requirements for local component sourcing and joint ventures. Component manufacturers in the U.S. can be far more easily monitored, while joint venture partners can keep an eye on Chinese companies. We should also have rules that Chinese cars have to host their software on American clouds and use U.S. telecom networks. All of these monitoring points will make it risky for Chinese companies to try any funny business.

The risk of Chinese espionage and sabotage via their companies’ cars (and other tech products) will never be entirely zero; it can only be managed prudently. Meanwhile, the benefits of letting Chinese EVs into the U.S., in a controlled manner, are increasingly obvious. Canada has shown the way; America can improve on its approach.

There are other reasons for this too, like producers understanding local taste and style.

“The move might even serve as a signal that if Trump starts threatening Canada the way he’s been threatening Greenland, Canada could geopolitically reorient toward China for protection.”

If Trump starts threatening Canada? It’s been about a year hasn’t it that Trump has been talking about annexing us? And now members of his administration are playing footsie with Alberta separatists https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cy8ylqx0zw4o

I don’t see us looking to a different authoritarian superpower for protection (our moves with China are about trade diversification). Our heart is with all of the democratic middle powers and with our liberal democratic friends to our south.

you are right but under the current mendacious and incompetent regime in the US probably won't happen. meanwhile the rest of the world move on from the USA EU free trade with India has concluded successfully and more to come. MAGA stupidity is just another way of growing poorer and more isolated.