Why Europe should resist the Second China Shock

Deindustrialization sounds peaceful and easy and pleasant, but it's not.

Europe has a lot on its plate these days. It’s facing a hostile Russia that has no intention of stopping with Ukraine. It’s dealing with tariffs and various other threats from an unpredictable and hostile Trump administration. And it’s struggling with internal unrest over migration from the Middle East and Central Asia. That would be enough to keep anyone occupied. But on top of all that, Europe is being buffeted by the Second China Shock.

The Second China Shock is another name for the flood of high-tech exports that China has been sending out around the world in the last few years. China’s economy is still suffering from the prolonged effects of the real estate bust that began in late 2021. In response, Xi Jinping’s government has unleashed the most expensive and wide-ranging industrial policy the world has ever seen, promoting high-tech manufacturing across a variety of sectors. Because the economy is in the doldrums, Chinese consumers themselves aren’t able to buy all the stuff that their government is paying Chinese companies to make — electric vehicles, ships, machinery, and so on. So the companies are selling that stuff overseas, anywhere they can, for cut-rate prices.

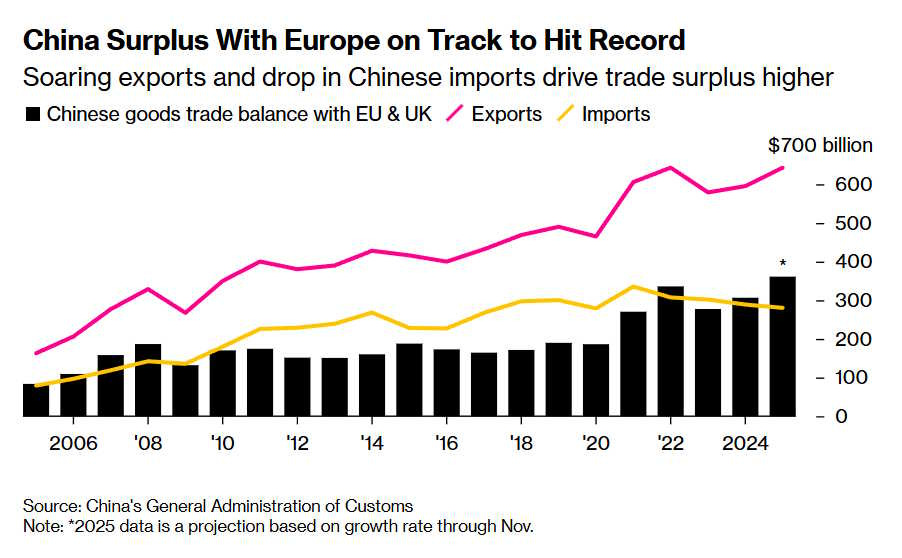

In Europe, that has manifested as a giant trade deficit with China:

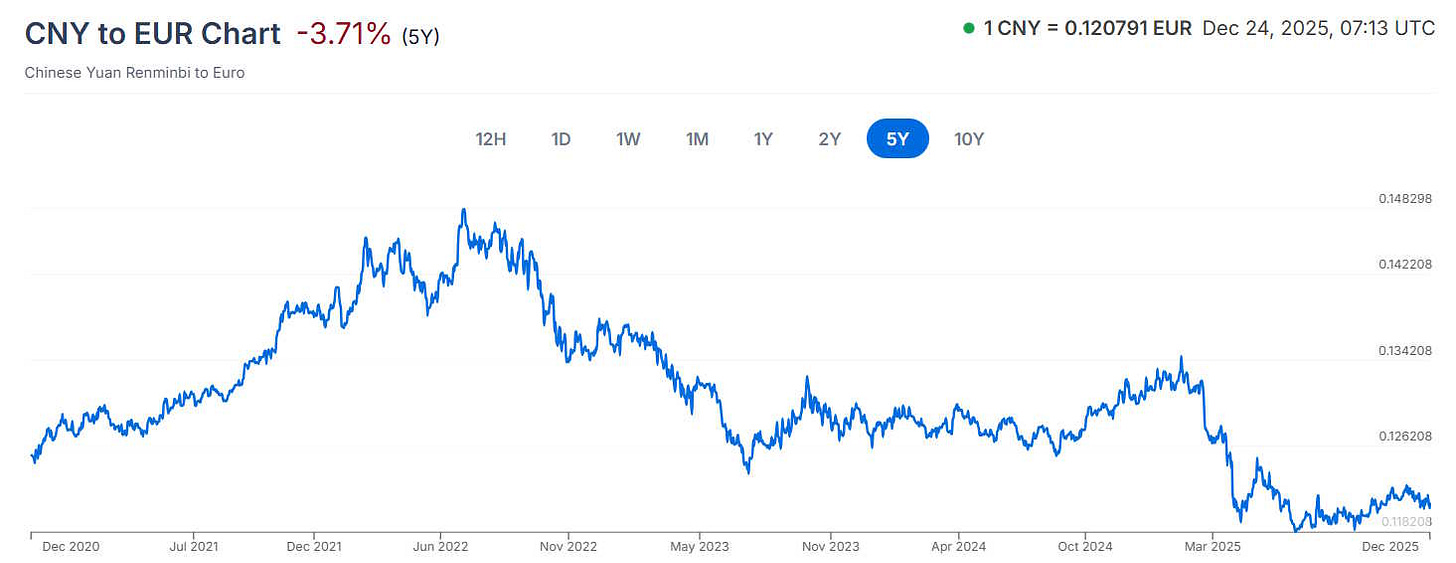

This flood of Chinese exports to Europe is being boosted by several tailwinds. First, China’s currency has gotten cheaper — partly as a result of China’s weak domestic economy, and partly because the government has pushed down the exchange rate in order to pump up exports. Shanghai Macro Strategist writes:

This combination — falling relative prices in China and a weaker currency — has made Chinese goods and services extraordinarily cheap in global terms…A vivid example: a night at the Four Seasons Beijing costs roughly $250, compared with more than $1,160 in New York. The price gap is so extreme that it no longer reflects relative productivity or income levels; it reflects a currency that has become fundamentally undervalued…At these valuations, it is virtually impossible for most countries to compete with Chinese exporters. The current level of the yuan is simply too cheap to support a sustainable rebalancing of global trade.

Here’s a chart showing the yuan’s recent depreciation against the euro:

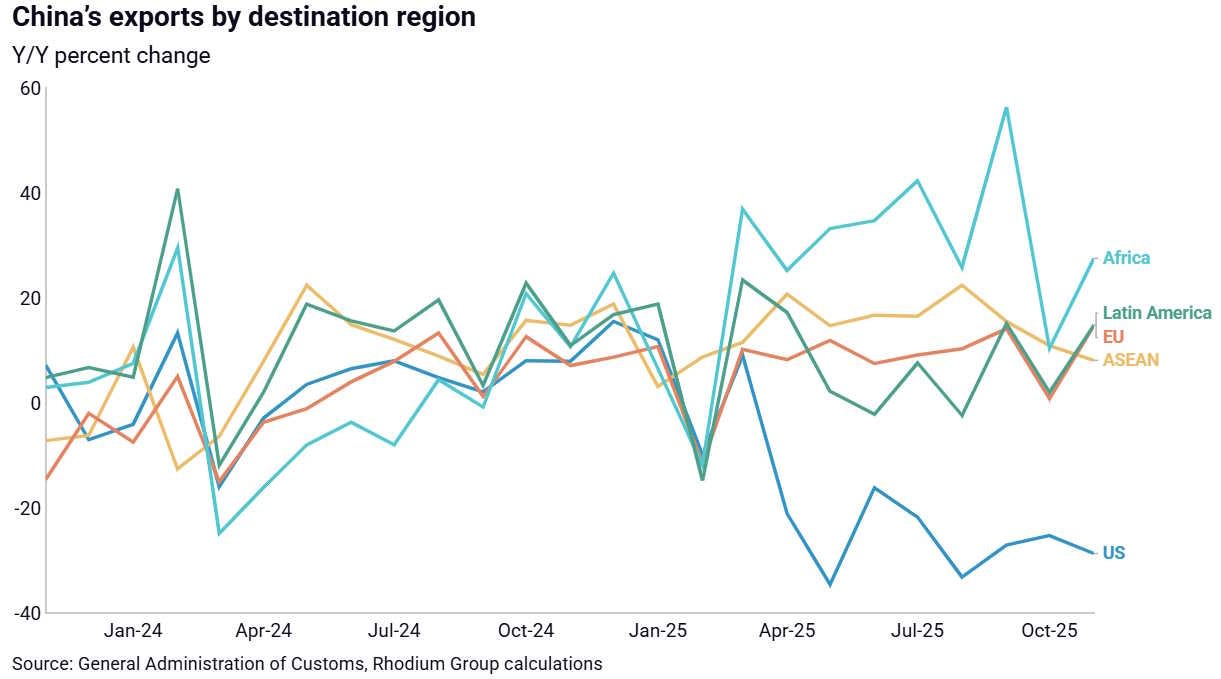

The second tailwind is Trump’s tariffs. Although Trump has backed off of most of his threats of tariffs on China, some important changes — like the end of the “de minimis” exemption for small packages — have gone into effect. And the threat of tariffs is probably prompting Chinese companies to seek other markets. As a result, Chinese exports to America are falling fast, while the country’s exports to other regions — Europe, Southeast Asia, and Latin America — are booming:

Some people claim that China’s surge of exports to these other countries is actually going indirectly to the U.S. Those people are wrong. As Gerard DiPippo has shown, “transshipment” to America is quite low. China simply found new customers to buy its products. Europe is the most important of those customers.

This means that although Trump’s boneheaded tariffs on allied countries have hurt U.S. manufacturing, his tariffs on China — and his threats of even higher tariffs on China — have partially insulated America from the Second China Shock. Europe as yet has no such insulation.

At this point you may ask: Who cares? China is selling a bounty of useful consumer goods to Europeans at cut-rate prices; why look that gift horse in the mouth? If a store in your neighborhood had a blowout sale, you’d enjoy it, wouldn’t you? And on top of all that, many of China’s fastest-growing exports to the EU — electric cars and such — are “green” technology that Europe has been trying to promote in order to fight climate change.

Given that Europe has so much else to worry about, why shouldn’t it just take the cheap Chinese stuff, enjoy the high-quality cars and the lower carbon emissions, accept deindustrialization, and focus on services instead? That’s basically what The Economist recommended in an article last month:

Indeed, the best hope of consolation for Europe lies not in stopping the China shock, but in weathering it. Manufacturing looms large in politics, but accounts for only 16% of the EU’s GDP, a far lower proportion than services (70%). Even in Germany its share is only 20%. The industries in which China is making inroads—cars, machinery, metals, pharmaceuticals and chemicals—account for more than 10% of the value of industrial activity in only a few European countries, notably the Czech Republic, Germany and Hungary…De-industrialisation, in other words, need not be synonymous with decay.

But as pleasant and easy as this might sound, it would actually be very foolish, for a number of reasons.

First, there’s the military angle. Health care and education and entertainment are nice things to have, but to fight a modern war you need drones, missiles, satellites, ships, planes, and vehicles of all kinds. And with Russia breathing down Europe’s throat, and America no longer a reliable ally, there is a good chance that Europe will soon have to fight a modern war against a high-tech opponent. Russia’s population is smaller than Europe’s, but its economy is now heavily oriented toward military manufacturing. Russian production is also now supported by China, whose companies are selling Russia weapons and even allegedly building weapons in Russia.

In order to resist that threat, Europe will need lots of manufacturing. That doesn’t just mean having European governments purchase ammunition and tanks from defense contractors. It means scaling up Europe’s civilian manufacturing of vehicles, electronics, chemicals, and so on, so that if Russia does start a wider war, Europe can repurpose those civilian industries for large-scale military production. If Europe allows itself to be deindustrialized, its military capabilities will be limited to whatever the government can purchase in peacetime.

The second problem is that Europe’s trade with China is increasingly unbalanced. Europe is not trading services for the flood of electric cars, solar panels, and so on that China is sending. Instead, Europe is writing IOUs. That’s what a trade deficit is — the writing of IOUs in exchange for imports. Robin Harding of the Financial Times recently warned about this unbalanced trade, in an eloquent article entitled “China is making trade impossible”:

There is nothing that China wants to import, nothing it does not believe it can make better and cheaper, nothing for which it wants to rely on foreigners a single day longer than it has to. For now, to be sure, China is still a customer for semiconductors, software, commercial aircraft and the most sophisticated kinds of production machinery. But it is a customer like a resident doctor is a student. China is developing all of these goods. Soon it will make them, and export them, itself…

[I]f China does not want to buy anything from us in trade, then how can we trade with China?…[W]ithout exports, we will eventually run out of ways to pay China for our imports.

A trade deficit is not a gift; it is a loan. That loan must be paid back. The Europeans who take out the loan may be insufficiently long-term in their thinking, effectively borrowing against their own futures to consume in the present. It’s up to government to look out for the prosperity of future generations.

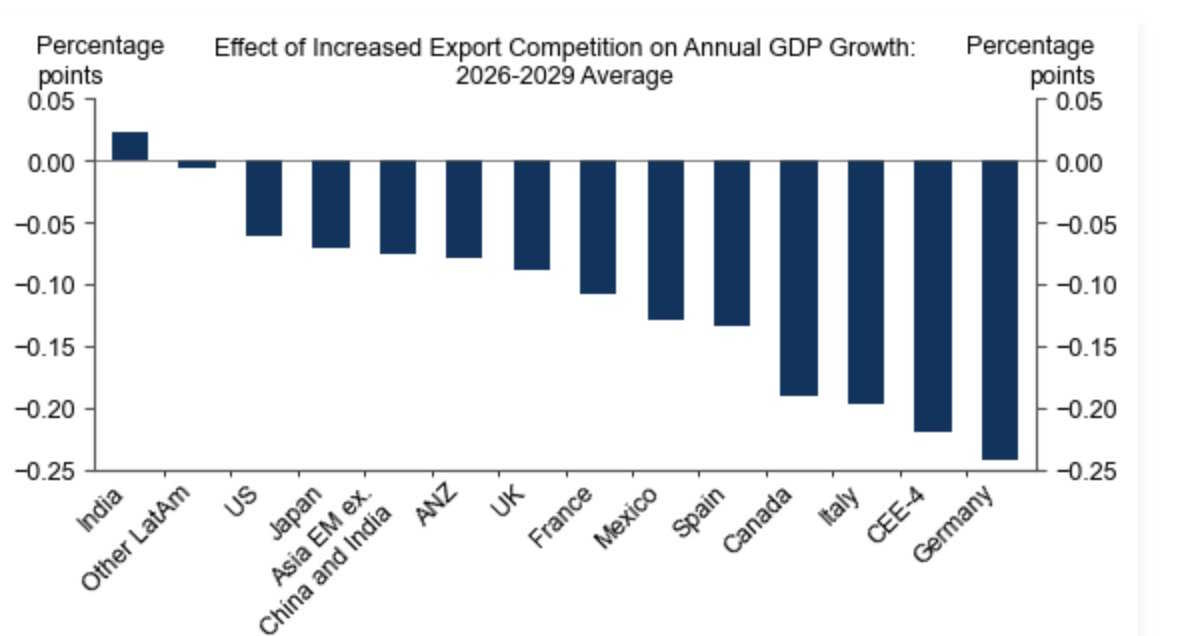

On top of all that, some people think that at extremes of unbalanced trade in high-tech industries, the conventional wisdom that trade is mutually beneficial might break down. Goldman Sachs recently released a report claiming that Chinese exports will actually make Europe poorer!

Greg Ip offers his thoughts in a thread:

Fascinating and important report from Goldman Sachs. They have upgraded long-term GDP of China because of increased exports, but see this as reducing, not increasing, rest of world GDP. Chinese displacement of domestic manufacturing swamps any positives from cheaper goods…

This confirms what I have long suspected: Chinese growth does not “contribute” to global growth except in the purely arithmetic sense. It does not actually create positive feedbacks that lift other countries’ growth. That’s by design...The point of Xi's "dual circulation" is to make the world more dependent on the Chinese industrial supply chain, while making China self-sufficient, that is buying less from the rest of the world. The model is inherently "beggar thy neighbor" (as Goldman notes)[.]

How would this work? Usually, when we think of “beggar-thy-neighbor” trade policies, it’s in the context of recessions; if aggregate demand is scarce, then trade deficits can make it worse. But while China is in a demand-driven growth slowdown right now, Europe is not. So there’s not really a macroeconomic reason to think that Chinese imports are making Europeans poorer.

Instead there must be a microeconomic reason. Obviously, even unbalanced trade is voluntary — Europeans want to write IOUs for Chinese goods — and we generally think that any voluntary trade must benefit both sides, or else they wouldn’t have done it in the first place. Thus, if Chinese imports actually make Europe poorer, it must be through an externality — some kind of negative spillover effect that the Europeans who buy BYD’s cars don’t take into account when they make their purchase.

In a New York Times op-ed back in July, the economists David Autor and Gordon Hanson — who famously coined the term “China Shock” in their research with David Dorn about the effect of Chinese imports back in the 2000s — seem to argue that such an externality exists:

China Shock 2.0…is where China…is aggressively contesting the innovative sectors where the United States has long been the unquestioned leader: aviation, A.I., telecommunications, microprocessors, robotics, nuclear and fusion power, quantum computing, biotech and pharma, solar, batteries. Owning these sectors yields dividends: economic spoils from high profits and high-wage jobs; geopolitical heft from shaping the technological frontier; and military prowess from controlling the battlefield. [emphasis mine]

What might that negative externality be? One possibility is that it’s what economists call a “pecuniary externality” — not a true destruction of value, but an appropriation of economic “rents” from one country to another. Paul Krugman’s New Trade Theory shows how because manufacturing is subject to increasing returns, trade barriers can sometimes reappropriate “rents” to your own country, by allowing your companies to gain scale. In other words, right now, BYD can produce things cheaply because its customer base is really big. If European countries raise trade barriers against BYD cars, their own car companies could gain more scale and become more efficient — and more competitive — by capturing the domestic market, thus transferring some of BYD’s profits to European automakers.

Another possibility is that preserving manufacturing increases a country’s innovative capacity. Manufacturing results in “learning by doing” — a kind of research that can’t be done in a lab, but which creates real knowledge and real productivity gains. There may also be a positive externality from having a ton of engineers in a country — what Brad DeLong calls a “community of engineering practice” — because these engineers get together and swap and combine their ideas. This is probably one reason why industrial clusters like Silicon Valley are so unusually productive.

If electric cars are made in China and shipped to Europe, all the innovation will be done in China. A lot of that innovation will be in the form of a bunch of little tricks that can’t easily diffuse to other corporations and other nations; in other words, the benefits will stay in China and make profit for BYD. But if Europe manufactured EVs for itself, most of the engineers who learned those tricks would generate knowledge for Europe.

Benigno et al. (2025) call this the “global financial resource curse”. The authors argue that corporate innovative activity requires corporate profits; if all the profit is being made in China, that will naturally starve Europe of a lot of innovation.

No European consumer who buys a BYD car is thinking about economies of scale or innovative capacity; they just want a car. But the decisions of all of those car-buyers could add up to a loss of scale and innovation for European companies that left all of Europe a bit poorer as a result.

So if Europe fails to fight the Second China Shock — if it embraces the comfortable euthanasia of deindustrialization — it will be militarily weaker in the face of the Russian threat, its international financial position will deteriorate, and it may be economically poorer as a result.

Those are good reasons for Europe to fight the Second China Shock. But how? Unfortunately, as Robin Harding argues, protectionism is going to have to be part of the solution:

The difficult solution [to the Second China Shock] is [for Europe] to become more competitive and find new sources of value…That means more reform, less welfare and less regulation…Even that, however, will not be enough in a world where China offers everything cheaply for export and has no appetite for imports itself…Which leads to the bad solution: protectionism. It is now increasingly hard to see how Europe, in particular, can avoid large-scale protection if it is to retain any industry at all.

This path is so damaging and so fraught it is hard to recommend it…It would mark a further breakdown of the global trade system…Yet when the good options are gone, the bad are all that is left. China is making trade impossible. If it will buy nothing from others but commodities and consumer goods, they must prepare to do the same.

Protectionism, be it with tariffs or non-tariff barriers, is essential in order to de-risk the reindustrialization of Europe. If a German or French company knows that at any moment, China’s massive industrial policy apparatus could swoop into their industry and put them out of business, they’ll be too shy to invest. Trade barriers are important because manufacturing investment is far less daunting behind that sheltering wall.

EU tariffs and other trade restrictions should only be on China — not on any other country (unless it’s doing large-scale transshipment of Chinese-made goods). In fact, Europe can lower trade barriers with more friendly countries in order for these countries’ manufacturing industries to attain large scale. Rush Doshi calls this “allied scale”.

The EU should also pair protection with export subsidies for European manufacturers. Foreign markets are just as important as the European market, and it would be a disaster to lose those. Europe can never match the scale, speed, and tolerance for waste of China’s industrial policy. But sometimes international buyers would rather hedge their bets and buy from Europe instead of onboarding themselves into the Chinese political-economic system. Just the other day, Vietnam decided to partner with Germany’s Siemens to build its high-speed rail, instead of with a Chinese company.

Another idea is to take a page from China’s book, and encourage Chinese companies to set up joint ventures with European companies in order to sell their products into the European market — or even force Chinese companies to do this, with “buy European” rules. If BYD has its car factories in Poland or Hungary, Europeans will be learning how to make electric cars well. Some of that knowledge will eventually diffuse to domestic European companies as well. And if Europe has to fight a total war against Russia, it can just nationalize those factories and use them for military applications.

Finally, Europe should think about taking action on China’s undervalued currency. This is the approach recommended by Brad Setser and Mark Sobel, who argue that pressuring China to allow the yuan to appreciate significantly would defuse a lot of trade tensions. China’s leaders think that Japan suffered economically after a similar agreement in 1985, but the threat of losing the European market might be even scarier.

This all sounds very grim, but on the bright side, EU action against the Second China Shock could be the beginning of a newer, more stable, more balanced, more equitable global economy. Tariffs on Chinese value added would force Chinese companies to move their factories abroad, to Vietnam or Indonesia or other poorer countries, which would help those countries industrialize. They would also accelerate China’s transition to a normal economy, by temporarily increasing involution and forcing China to curb overproduction. And an appreciation of the Chinese currency would make the global financial system more stable.

But in any case, Europe has little choice at this point. It can’t afford to become a deindustrialized, service-intensive backwater — especially not in the face of all the other threats it faces. The Second China Shock must be resisted.

Update: Obviously, most of these arguments also apply to the U.S. I wrote about trade deficits as loans here:

And I wrote about how tariffs on China (along with no tariffs on allies) should form part of America’s trade strategy:

I also explained why targeted tariffs (i.e. on China’s high-tech products) are much better than across-the-board tariffs:

"A trade deficit is not a gift; it is a loan. That loan must be paid back. The Europeans who take out the loan may be insufficiently long-term in their thinking, effectively borrowing against their own futures to consume in the present. It’s up to government to look out for the prosperity of future generations."

This paragraph confuses me. Could we not substitute "Europeans" with "Americans" and have the statement be just as true? I've followed your lead on the tariff issue all along -- I'm not an economist, so I have to pick one to follow. However, I don't recall you using this description when writing about Trump's tariffs. But I do understand your arguments about very targeted tariffs.

You could have easily substituted the US in the article for Europe. Unless Europe demands China trade with them, the outflows of Euros can develop into a problem. If China never redeems those Euros for goods, it means they didn’t get full value for their exports. Afterall what is China going to do with them?

If they redeem them at a later date, due to inflation, they will purchase less. If the amount of outstanding Euros is never used, it could be a liability if China wants payment in political favors. Let's say China sells Euros on an exchange for less, thereby lowering the Euro's value. That could be very bad.

China is looking for dominance; walking into the jaws of an alligator is plain dumb. My argument with Trump’s hamfisted tariff campaign is not that he is seeking a fairer trade. It is that he doesn’t look at services, only goods. He is tariffing intermediate goods that American manufacturers need to make their finished goods. America sells a large volume of services worldwide.