We're not ready for the Big One

A war over Taiwan is a real possibility, and the U.S. is not prepared.

“Down here it was still the England I had known in my childhood: the railway cuttings smothered in wild flowers…the red buses, the blue policemen—all sleeping the deep, deep sleep of England, from which I sometimes fear that we shall never wake till we are jerked out of it by the roar of bombs.” — George Orwell, 1938

It feels like something that was long sealed away has broken loose. In 2022 we saw a nuclear-armed great power invade and try to conquer a neighboring country. Now Iran is threatening to go to war with Israel, and the U.S. is sending carrier strike groups to the region to deter it. Meanwhile, Azerbaijan may be getting ready to invade Armenia, Serbia might invade Kosovo, and other wars and atrocities are breaking out in various corners of the world.

In a post last week, I hypothesized that the waning of American deterrence is a big reason the world seems to be slipping into a more warlike, anarchic state. I am not an expert in foreign policy, but Paul Poast and Hal Brands both are, and they offered the same hypothesis. In particular, I think many Americans fail to realize the extent to which the war between Israel and Hamas is in part an extension of a larger great-power struggle, pitting the Russia-Iran-China axis against the U.S. and its allies. This “New Axis”, as I’ve called it, is on the march, emboldened by the growth of Chinese economic power and by America’s internal division and shriveled defense-industrial base.

But the final shoe has yet to drop. Russia’s dysfunction has bogged it down in Ukraine, and Iran’s military power is limited, so these wars are unlikely to spread and lay waste to whole regions. Nor will the global economy be upended, since Russia and Iran are both petrostates. The real cataclysmic event will be a war between the U.S. and China over Taiwan.

If this ends up taking us by surprise, we’ll have only ourselves to blame. Xi Jinping constantly says he’s preparing China for war. Chinese state media is airing programs about how an attack on Taiwan would proceed, and the Chinese military has released an animation depicting an attack plan. China’s near-constant air and naval exercises around Taiwan look an awful lot like practice. And the country’s economic slowdown just gives it a further incentive for military adventures.

I don’t think most regular Americans are mentally prepared for a U.S.-China war, or have thought deeply about what it would entail. Most of us — myself included — were surprised by Putin’s willingness to invade Ukraine, and by the ferocity and escalation potential of the Israel-Hamas war. This doesn’t seem atypical; when I read personal accounts of World War 2, I’m always astonished by how the narrators discounted the possibility of America entering the war all the way up until they minute the bombs started falling on Pearl Harbor.

But the Roosevelt administration anticipated the war years in advance, and took action to prepare. Similarly, whether a war with China eventually comes or not — and I fervently hope it will never come — we ought to start preparing now. The wars that have erupted in Europe and the Middle East should serve as a warning, which we ignore at our grave peril. We shouldn’t concentrate so much on the wars that are happening today that we forget to think about the war that could happen tomorrow.

Anyway, I’ll talk about how I think business and government can prepare, but first I think I should address the skepticism I commonly encounter when I warn people about the chances of this war actually happening.

“But America wouldn’t really go to war with China over Taiwan…would we?”

My favorite character in Lord of the Rings was always Gandalf — not just because he’s a melodramatic, bumbling old wizard who somehow always comes through when the chips are down, but because he sees danger coming that others miss. One of the most memorable scenes in The Two Towers is when Gandalf is telling King Theoden that Saruman’s armies are about to sweep down and wipe him out. Theoden’s traitorous adviser, Wormtongue, scoffs at Gandalf’s warnings, but eventually Gandalf manages to convince Theoden that the danger is real. I was always impressed that Gandalf managed to succeed where Cassandra failed.

Sometimes when I talk to Americans, especially in the tech industry, about a war over Taiwan, I feel a little of the frustration Gandalf must have felt. I often encounter a look of horrified disbelief, as people ask me: “We wouldn’t really go to war over Taiwan, would we?”

But as comforting as it might be to imagine America sitting serenely to the side while people in Asia fight their wars, this is highly unlikely to happen. The reason is not that TSMC is essential to the global semiconductor supply chain, or really anything intrinsic to Taiwan itself. It’s that if China attacks Taiwan, it’ll probably attack U.S. bases first.

I tried to explain this in a post a year ago:

The post gets a little into the weeds of game theory, but the basic message is pretty simple. The U.S. has a bunch of military bases near Taiwan, including Okinawa, Guam, and now the Philippines. Those bases have aircraft, missiles, etc. that could sink a Chinese invasion fleet fairly easily. So if China decides to invade Taiwan, it’ll have to make a choice. Either:

Proceed with the invasion knowing that the U.S. can choose to foil it any time it chooses, with catastrophic Chinese casualties and catastrophic loss of prestige for Xi Jinping and the CCP, or

Destroy or severely damage U.S. bases before the invasion, using saturation missile strikes.

Now if you are Xi Jinping in this situation, and you’re fully committed to staking your life’s work and your entire regime’s legitimacy on this invasion, which of these options are you going to pick? Remember that Joe Biden has repeatedly and explicitly vowed to come to Taiwan’s defense, and his administration has only said afterwards that the U.S. position hasn’t changed. Are you going to stake everything on the chance that this was just bluster?

Maybe, maybe not. And if Xi Jinping calculates that staking his whole future on U.S. indifference, restraint, and mendacity is a bad idea, then he will take out our Pacific bases before the invasion. And if he does that, it’s Pearl Harbor 2 — the U.S. will immediately be at war with China.

There’s another factor here to consider, which is Japan. In recent years, Japanese planners have made it clear that they consider an invasion of Taiwan to be a direct threat to Japan. The country is no longer pacifist, and is engaging in a major military buildup to defend against China. In a 2020 blog post, Tanner Greer explained why Japan is so worried; with control of Taiwan, China would much more easily be able to bombard and/or blockade Japan.

It’s possible that Japan would take the lead in trying to stop a Chinese invasion fleet. This would lead to war between the two countries. The U.S. is Japan’s treaty ally, so we’re legally obligated to come to their defense if they’re attacked. This would also make it difficult for the U.S. to stay out of the war.

So to sum up, China has a significant chance of invading Taiwan in the next few years. And if it does happen, there’s a very significant chance the U.S. will go to war with China as a result. This war would eclipse anything in Europe or the Middle East. It’s not a tail risk — i.e., a highly unlikely but catastrophic event that we need to hedge against. It’s a realistic, major, imminent risk. We can’t get by with just hedging; we need to actively prepare.

U.S. businesses must diversify out of China

The U.S. private sector is fairly enmeshed with the Chinese economy. We import over $500 billion from the country every year (and it’s not clear whether a value-added measure of trade would decrease that number substantially at this point). The U.S. has begun decoupling from China, but only slowly — the share of our share of imports that we get from China has probably fallen from 21% to 18%, according to Gavekal Dragonomics. 18% is still a lot. Some of those imports are consumer goods that American sellers import to sell to consumers; many are intermediate goods that are crucial inputs to production processes in U.S. manufacturing.

Imagine what will happen to those imports on the day China conducts a saturation missile strike on U.S. bases. The imports will mostly grind to an immediate halt. This will happen for several reasons. First, there will be a risk to merchant shipping near China. Second, China will likely cut off imports (redirecting the factory production to its military). Third, the U.S. government and U.S. society will put a lot of pressure on companies to stop buying components from China.

We already have a preview of what a sudden cutoff of a few Chinese imports looks like — the Covid pandemic, where China suddenly started keeping its manufactured medical supplies for itself. It took months for the U.S. to start producing its own masks, ventilators, and Covid tests in sufficient quantity. Now imagine similar cutoffs across the entire U.S. economy — not just consumer goods, but all-important parts and components that no one in the U.S. even knows how to make anymore.

And add a cutoff of raw materials — China doesn’t mine most of the world’s critical minerals, but it does the processing and refining for most of them. Imagine American companies caught without raw materials, and needing to spin up hundreds of billions of dollars’ worth of manufacturing from scratch after years of total neglect.

This is the risk that U.S. businesses are facing. For any company that sources entirely from China, the risk is existential. So a company in that position has two basic choices: Either shrug and accept existential risk, or diversify supply chains out of China and turn an existential risk into a large but manageable risk.

This is an important difference. An American company with zero suppliers outside of China on the day a war starts will find itself looking around desperately for someone to source from; a company with some suppliers outside of China will be able to scale up its purchases from those suppliers, and use their engineers and managers to teach other suppliers. In other words, companies that have diversified out of China will be much quicker to get production fully back up and running after a war starts.

A number of American companies have been trying to diversify out of China in recent years — most notoriously Apple, which has begun moving production to India and elsewhere. But there’s an important wrinkle here. Making part of your supply China-proof doesn’t just mean that you buy some products from companies that aren’t located in China. It means that those suppliers also buy some products from companies that aren’t located in China, etc. etc., all up the supply chain, all the way to the raw materials. It means that there’s an entirely intact supply chain for your intermediate goods that never touches China — or which touches China only in unimportant ways that can be easily and quickly replaced in a war situation.

What this means is that American businesses can’t just switch their sourcing; they have to audit their whole supply chain, and try to help their suppliers switch their sourcing as well. Big businesses like Apple can probably do that; the plethora of smaller American businesses don’t have the resource for supply chain audits.

This is one place where the U.S. government can come in. The government is already doing supply chain audits, so it can lend some of this expertise to American businesses for free. This will require quite a bit of scaling-up on the government’s part, and the enlistment of private-sector partners in the effort. But it’ll be worth it, because successful supply-chain audits throughout most of American industry will make the U.S. economy far, far more proof against collapse if and when China imports vanish into thin air.

The U.S. government must rebuild the defense-industrial base

It’s useful, I think, to remember how the U.S. prepared for World War 2. The government didn’t simply leap into action on December 7th, 1941 and start war production from scratch. The Roosevelt administration saw the risk of major war, and had been laying the groundwork for the war effort for several years. If you haven’t read about this, I suggest starting with David Kennedy’s Freedom From Fear, Arthur Herman’s Freedom’s Forge, and Mark Wilson’s Destructive Creation.

To make a long story short, FDR and his administration started preparing for a possible World War 2 years in advance. The B-17 bomber, one of the war’s most iconic airplanes (and one my grandfather fought in), was first planned in 1934. In 1938, when it seemed likely that Hitler would start a war in Europe, FDR increased defense appropriations. In 1939 when the war actually started he did so again, and in 1940 he declared a state of national emergency and began setting up the Office of Production Management. But American production really kicked into high gear in March 1941 with Lend-Lease, which gave Britain (and later the USSR) materiel to fight the Nazis. All of this happened well before the bombs fell on Pearl Harbor.

The U.S. government needs to be equally far-sighted today; we do not have a decade or even five years to wait in order to begin preparation. Like in 1938, it’s not yet certain that a great-power war will actually happen, but it’s likely enough that the Biden administration should begin hedging the country’s risk.

Supply chain auditing and incentives for reshoring, near-shoring and friend-shoring are important tasks. Industrial policy is helping to build up the U.S. electronics and energy industries. But the most urgent — and most neglected — task is to rebuild the U.S.’ defense-industrial base.

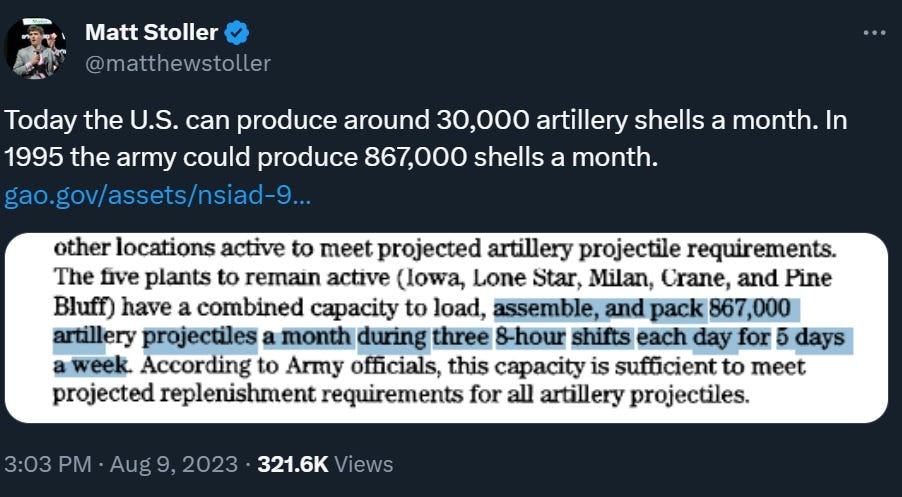

Americans don’t seem to realize just how shriveled our military production capacity has become. Total defense spending numbers tell the story less clearly than a few specific facts. To support Ukraine, we’ve been increasing our output of artillery shells, but the quantity is still woefully low. We can currently make about 28,000 shells a month, and the Pentagon has plans to increase that to 100,000 by 2025. And yet in the mid-1990s we had the capacity to make 867,000 a month:

Or consider shipbuilding. U.S. shipbuilding capacity has withered to such a point that some intelligence estimates say we can only produce 0.5% of the ships China can make.

Obviously these lopsided production statistics also apply to things like missiles and drones that are even more relevant to a modern battlefield than traditional artillery shells.

It doesn’t matter how many dollars America spends on the military on some spreadsheet; if we can only make ammunition and ships and missiles and drones at a tiny fraction of the rate China can, the U.S. will lose a war to China. It’s as simple as that. Wars almost always go on longer than the people who start them expect — look at how Putin thought he’d conquer Ukraine in a week, or look at how the countries who fought World War 1 thought it would be over in a few months. The U.S. and China will quickly use up their starting stockpiles of weapons, and then the U.S. will be up against a manufacturing juggernaut — a neat reversal of our position in World War 2, when we were the juggernaut.

The defense-industrial base must therefore be restored, and very quickly. Obviously the procurement process needs reform, and the DoD needs to be able to buy new technologies like drones from small startup companies in the private sector. But high-tech startups are unlikely to solve prosaic needs like shells and ships; for that, the U.S. needs more traditional manufacturing companies. It will simply not do to have critical military components made by one tiny aging factory owned by a 70-year-old guy in Iowa. The industrial commons must be restored to what it was in the 1980s.

A few leaders realize this, but the requisite urgency doesn’t yet seem to exist on both sides of the political aisle.

The U.S. government does have a tool that can help here — the Defense Production Act, which allows the government to basically requisition production from private companies. But simply telling Ford or GM to start making missiles won’t do the trick; the U.S. government will have to spend money. That will, unfortunately, mean cutting back on health spending or something, since the deficit is already so large that there’s going to be mounting pressure for fiscal austerity. That’ll undoubtedly be a tough sell politically; I don’t have any good answers for that. But waiting until the missiles start flying to start making the hard fiscal choices required to rebuild a shriveled defense-industrial base seems inadvisable.

In any case, the larger message here is that neither the U.S. private sector nor the public as a whole, nor even the government, is properly prepared for the risk of a war with China. That war may never come, and I strongly hope it never comes. But being caught unprepared would be a disaster, not just for the U.S. and its allies and global security and freedom and all that, but for the American people themselves, who would suddenly find themselves without consumer goods, shut out of key global markets, etc.

It’s simply better to prepare, both mentally and with policy. If the wars in Ukraine and Israel have taught us anything, it’s that we live in a much more volatile and dangerous world than we did five or ten years ago.

Good post. More antiship missiles for Taiwan, please.

Sure, Xi has a lot of ships. But missiles are cheaper. The USA can still outspend Xi if our strategy is missile-per-ship instead of ship-per-ship.

Xi can't invade, or even gracefully blockade, if Taiwan has a porcupine's worth of missiles to saturate Xi's navy with explosives. Heck, if you expect in advance that you'll get all your precious ships sunk to the bottom of the Taiwan Strait, you don't launch a war in the first place.

If Taiwan is well-armed enough, far in advance enough, this whole disaster can be deterred.

Another wrench to throw in is what happens if America re-elects a self-obsessed autocrat as president? The former president has remarked on how little he cares about Taiwan (quoted in John Bolton's book) and is generally inept and unreliable. What would re-electing him say to Taiwan and China (let alone Japan, NATO, Ukraine, etc)? We need to do what you say: rebuild the defense-industrial base, diversify out of China, build deterrence through strength and allies... but all these things require competence and planning and trust from allies. The world is in a dangerous moment and it makes the work of defeating Donald Trump especially urgent.