China's slowdown and the incentives for war

Answering the looming question that's on a lot of people's minds.

By now, China’s slowdown has been covered from almost every possible angle. If you’re following the story, by now you’ve read not just about the details of the economic crisis itself, but also about the roots of the problem, the headwinds going forward, the political and social effects in China, and the effects on the rest of the world. But there’s one important question that I haven’t seen anyone else cover yet, and which many people have been asking me about. So I thought I’d write a post about whether China’s economic troubles will prompt it to start a war.

Obviously, whether China decides to start a war is heavily dependent on lots of political factors that I’m not really equipped to analyze. Whether Xi Jinping thinks a war would help shore up his legitimacy in the face of various policy failures, or whether Chinese nationalistic sentiment demands that the leadership take aggressive action, or whether China sees a closing window of opportunity for retaking Taiwan are all questions that I just don’t know the answer to.

But what I can do, at least to some extent, is think about the economic costs and benefits. Obviously leaders’ decisions on war and peace are not always motivated by rational economic calculations — we all know the story of WW1 — but at the same time, costs and benefits probably do matter to some extent. I can see at least three factors that seem like they could plausibly affect Xi Jinping’s mental calculus here: the end of catch-up growth, the need for stimulus to fight the economic downturn, and China’s increasing economic self-sufficiency.

Unfortunately, all of these factors seem to point in the same direction: an increased risk of bellicosity and conflict. So this is going to be a scary post rather than an optimistic one. I don’t want to be alarmist or claim that war is coming; I think there’s still a good chance that Xi refrains from starting a war. But I think it’s important to recognize the economic factors involved, and be prepared for increased risk.

War isn’t a threat to catch-up growth if catch-up growth is over

In introductory economics textbooks, a common example is the “when to cut a forest” problem. Basically, a forest grows at some rate over time, and you’re trying to decide when to cut it down and sell the wood. If all you wanted was simply to get the maximum amount of wood, you’d actually never cut it down; at any point in time it would always make sense to wait and let it grow some more. But of course in reality we care about time, too; there’s some cost to waiting. Maybe you’re impatient (you’re not immortal, after all), or maybe there are bonds out there you could be investing the money in after you sell the wood. This is an opportunity cost; it’s the cost of delaying your payout. In any case, the assumption is that the forest’s growth slows over time, so when the rate of growth slows to less than the opportunity cost, you go ahead and cut the forest down.

That’s perhaps not the most environmentally friendly example, but I think there are uncomfortable parallels to China’s strategic calculus during its economic rise. A country’s potential military power increases with economic growth — more manufacturing capacity means you can make more weapons and supplies, and a higher technology level means your weapons will be more sophisticated. So even if China wanted to conquer Taiwan in 1996 or 2004 or 2015, its economy was growing so fast that it made sense to wait — to hide their strength and bide their time, in Deng Xiaoping’s famous words.

Starting a war would be a way of getting the payoff from economic growth, just like cutting the forest is the payoff from letting the forest grow. And economic growth increased the size of that payoff, since it increased the chances of winning the war (and any follow-on wars after that).

But as of 2023, China’s rapid catch-up growth is probably over, or at least mostly over. Economists’ forecasts are typically slow to adjust, but in light of the current slowdown, they’re drifting downward:

[Bloomberg] economists now see growth in China’s economy — the world’s second largest — slowing to 3.5% in 2030 and to near 1% by 2050. That’s lower than prior projections of 4.3% and 1.6%, respectively.

And of course with the fallout from the real estate bust not even fully realized yet, there’s a chance China could do substantially worse than this over the next decade. Nor is it just the real estate bust weighing on Chinese growth — before the pandemic, growth had already been falling for a decade thanks to a productivity slowdown:

And in the future both demographic and political-economic headwinds will weigh on the Chinese economy.

Of course, military power is relative, and China’s economy is still forecast to grow a little faster than that of the U.S. and its allies for a while. But remember from the forest-cutting example that we also have to take opportunity cost into account. Xi Jinping is 70 years old, and he may want to see Taiwan conquered or U.S. power overthrown before he leaves power. Chinese nationalists may be impatient as well. Risk is also an opportunity cost; the longer Xi waits, the greater the chance that some new factor will emerge to make Chinese hegemony harder to establish. Maybe a more powerful India, or the emergence of a NATO equivalent in the Pacific, etc.

So as soon as the growth rate of China’s military potential drops below the opportunity cost of waiting longer, we enter what Hal Brands and Michael Beckley call “the danger zone”.

China is somewhat hardened against economic isolation

Of course, one key feature of the “cutting a forest” analogy is that once you cut the forest, you don’t have a forest anymore. For the analogy to work, there has to be some cost of starting the war. One such cost is the risk of actually losing the conflict, which would presumably make the country pretty unhappy with its current leadership. But another cost would have been the sudden loss of access to the markets, investment, and technology of the West, and possibly to critical resources from global markets.

So it’s important to note that all of those external dependencies have decreased in recent years. First, there’s investment. FDI was a big part of China’s growth story, since it provided not just jobs and capital but also influxes of foreign technology, through joint ventures between foreign and Chinese companies (and also through espionage). But now FDI is a much more modest part of the Chinese economy:

And that’s not even taking into account things like the current slowdown, Xi’s crackdown on tech companies, a suddenly hostile climate for foreign business in China, de-risking by multinational companies, investment restrictions by the U.S. and other governments, and so on. China’s role as the world’s preferred destination for investment is basically over. And that means one less foreign dependency to worry about in a war situation.

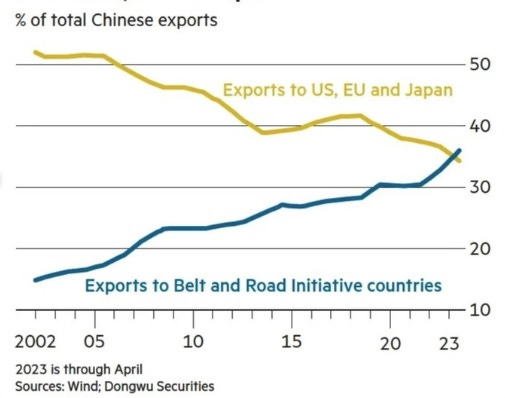

As for developed-world markets, those are still important to China, but they’re becoming less important on the margin as exports to the developing world increase:

Of course, some of this is intermediate goods trade — countries like Vietnam importing and assembling Chinese components into products for sale in developed-world markets. But much of it is not. And remember that China has, in general, become less of an export-led economy in recent years, even before the recent slowdown caused a sharp drop in total exports.

As for developed-world technology, this has become less important for China as its manufacturing industries have approached the global frontier. This is why China has become less import-dependent in recent years. A recent McKinsey report explains:

China has moved beyond assembling imported inputs into final products. It now produces many intermediate goods and conducts more R&D in its own domestic supply chains….In computers and electronics, for instance, Chinese companies are developing the kind of sophisticated smartphone chips that China once imported from advanced economies.

Meanwhile semiconductors, the most important sector where developed countries still retain a slim edge, are now subject to export controls. And China’s ability to appropriate technologies by buying companies in the U.S. and other developed nations has been impeded by inbound investment restrictions. Between these measures and the drop in FDI into China, much of the country’s appropriation of foreign technology will probably now shift to traditional Cold War-style espionage rather than voluntary economic partnerships.

What about access to commodities? China could probably feed itself in the event of a conflict. It imports about a third of the food it consumes, but it would likely have overland access to Russia and parts of Southeast Asia in wartime, so it would likely be fine. Nevertheless, Xi has fixated on increasing the country’s food security, which should make the world a bit nervous.

Oil is often talked about as a major choke point for the Chinese economy. The fact that China imports most of its oil, and these imports have to travel through a bunch of maritime choke points, has been labeled the “Malacca dilemma”. In a war situation, the U.S. and its allies would try to blockade China from receiving oil shipments, and China’s navy would try to break the blockade. But in the end, I’m not sure that China is critically dependent on oil imports. The country has the world’s second-largest coal reserves, and like Nazi Germany in WW2, they can use this coal to make synthetic fuels via the Fischer-Tropsch process. It’s not nearly as cheap as imported oil, but it’ll do. (China would also likely construct oil pipelines to Russia.)

That leaves various minerals. China dominates the processing of many minerals, but in wartime they might get cut off from some of the actual mines, especially in places like Australia. This dependence is hard to eliminate completely, because no country has all the minerals required for an advanced industrial economy. But that would always have been the case, and is just a big inherent risk of starting a major war.

In other words, although China’s economy is not an entirely self-contained fortress, it’s far more self-sufficient across the board than it was even just a few years ago. And part of that self-sufficiency is actually due to the current economic slowdown, since much of the developed world’s desire to open itself to China was because of the lure of the Chinese market. With that lure rapidly fading, China has less to lose from adopting a confrontational attitude toward the rest of the world.

War is the ultimate stimulus

While the economic cost China would pay from going to war is less than it was, the current slowdown may have also created new economic benefits. A shift to a war economy would likely act as a massive fiscal stimulus, to pull China out of the hole it’s fallen into.

China’s youth unemployment is so bad right now that the country actually just stopped publishing the numbers. At last measurement, it was over 21%. Mass unemployment always creates a danger of unrest, but youth unemployment is probably especially worrisome, since young people are more willing and able to run riot. The country’s leadership has so far shown a marked reluctance to deploy large-scale fiscal stimulus, and any efforts to restore the real estate sector to its bloated pre-crash state will probably be fruitless. This sets the stage for years of elevated joblessness — not as bad as the Great Depression, but definitely something the CCP would rather avoid.

And one way to avoid it — to bring the country rapidly back to full employment — would be a major war. War production, starting with Lend-Lease in 1941, was how the U.S. finally got unemployment down from the very high levels of the Depression.

Some Americans think of a war over Taiwan or in the South China Sea as a short, sharp affair, with some ships and planes shooting at each other and some missiles being launched, and the issue being decided very quickly. But as the Ukraine War has reminded us, wars are rarely as short as people expect at the outset. Even if the U.S. somehow prevailed in the early fighting and inflicted serious damage on China’s fleet and missile bases, China could just build another fleet and more missile bases.

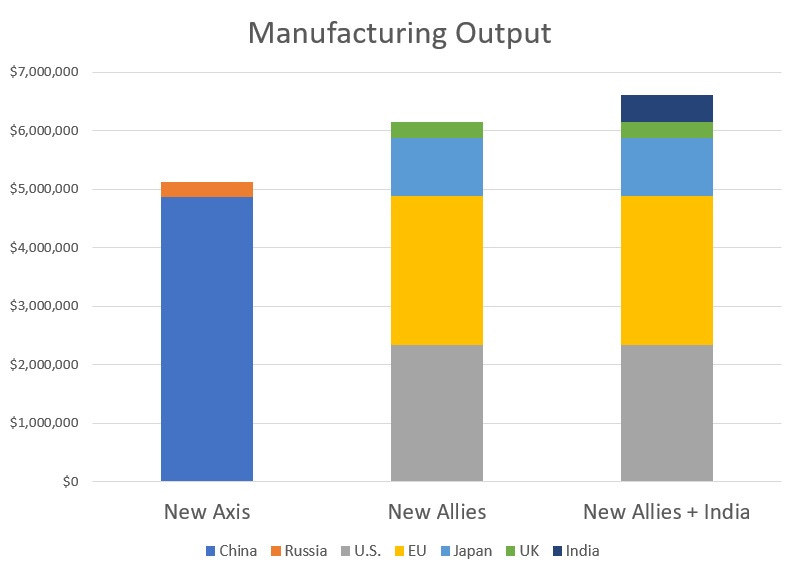

The weapons of the U.S. and its allies might be a bit superior to what China wields, but China would attempt to overwhelm slightly higher quality with much greater quantity. Remember, we’re talking about a country with the manufacturing capacity of the U.S. and Europe combined:

We have seen China accomplish absolutely amazing feats of production and resource mobilization in recent years. We’ve seen them build a high-speed rail network bigger than the entire rest of the world combined in just 15 years. We’ve seen them go from an also-ran in the auto industry to the world’s leading car exporter in just a couple of years. They would obviously apply this same overwhelming mobilization approach to a war with the developed nations.

This would give essentially everyone in China a job to do, ending the real-estate-driven recession in its tracks. And since the war would be a high-tech one, with each side trying to out-innovate the other at breakneck speed, it might also turbocharge domestic Chinese innovation. As economists Daniel Gross and Bhaven Sampat have written, something like this happened for the United States during World War 2:

World War II was one of the most acute emergencies in U.S. history, and the first where mobilizing science and technology was a major part of the government response. The U.S. Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD) led a far-ranging research effort to develop technologies and medical treatments that not only helped win the war, but also transformed civilian life, while laying the foundation for postwar innovation policy after it was dissolved…In this paper we bring OSRD into focus, describe how it worked, and explore what insights its experience offers today. We argue that several aspects of OSRD continue to be relevant, especially in crises[.]

World War 2 wasn’t just the thing that brought the United States all the way back from the Depression; it made the U.S. the center of global innovation for many decades to come.

That history is probably on China’s leaders’ minds as they contemplate starting a major great-power conflict. Of course there are other possible outcomes as well — Germany, Japan, Russia, and Britain didn’t benefit economically from the world wars, to say the least. But with their economy in the dumps and their technology under pressure from foreign restrictions, China’s leaders may see the potential upside of war mobilization as a benefit to add into their mental calculations.

Ultimately, I still think that war would be a very foolish choice for China — the risk of having its rise crushed by a global coalition, or being obliterated in a nuclear exchange, outweighs the modest gains from conquering pieces of Asia. China is already a very large country, with little need for additional territory or population; conquest and hegemony simply aren’t worth the risk.

But as leaders from Kaiser Wilhelm to Vladimir Putin have shown, national leaders are not always wise or risk-averse. And when the economic costs of war decrease and the potential upside increases, their natural overconfidence and aggression may gain the upper hand. Unfortunately, every economic factor I can think of seems to point to a major war being less risky for China on the margin compared to five or ten years ago. All I can say is that I hope cooler heads prevail and deterrence succeeds.

Update: There is some evidence that China is already responding to a slowing economy by accelerating its defense buildup.

"the economic cost China would pay from going to war"

Noah's argument has a glaring flaw. He talks about the economic downside of war primarily as a loss of access to foreign markets. The biggest and decisive economic cost would be the destruction of all those gigantic factories situated along the coast within easy reach of American missiles. American means of production are by no means as vulnerable. We don't need to target civilian residential areas. Doubtless the destruction of several hundred factories, the factories where the Chinese people work, would make a vivid impression and make It obvious to them how wrong headed their leadership is.

Indeed, war might even be prevented by the US pointing this out to Chinese leadership.

We all know that Xi wants a leaner, meaner China, but despite his current frustration, he is also aware that the Chinese people have their limits. They don't want to see the country go 30 years in reverse.

I have many thoughts more thoughts on this issue, and a few of them are expressed in my Substack post.

Are the United States and China “At Each Other’s Throats?”

https://kathleenweber.substack.com/

The forest analogy leaves out one other possibility. If the forrest is large enough, selective cutting will allow for the taking of mature trees, giving the youngr ones room to grow. If done correctly, this will allow the forrest to survive for a long period of time. This has been accomplished in the Southern portion of the United States and has worked for over 100 years. Some reports seem to indicate that todays forrest is larger and more productive than ever before. Selective cutting also allows for the removal of brush and this provides less fuel for forrest fires.

In the past, wars provided away for countries or empires to grow and become richer, but that is no longer possible. War is so destructive that the captured terriorty is basically worhtless - from an economic perspective.

The one thing China would gain, but only in their own belief perspective, is to capture a run away territory that they feel should be under their control. They have destroyed any semblence of freedom in Hong Kong and they would do the same in Taiwan. Resistence to Chinese control will be very strong and could lead to a nuclear exchnage between China nd America. If so, everyone loses.