The age of SASEA

South Asia and Southeast Asia are globalization's next frontier.

Most talk about globalization these days is doom and gloom. It’s all U.S.-China decoupling, tariffs, export controls — the fragmentation of the world economy into competing geopolitical blocs. The assumption, whether stated or unstated, is that developing countries are going to suffer in this new fragmented world — shut out of developed markets by protectionism, and outcompeted by a flood of subsidized Chinese export goods. Some pundits talk glumly of countries being forced to rely on services instead of manufacturing development; even a few people who previously supported industrial policy have now fallen into the mental trap of thinking that China is the only country that will ever be able to make physical goods at scale. Others worry that slower global growth due to trade wars will negatively impact resource exporters in Latin America, the Middle East, and Africa.

But as I’ve been arguing for a while now, there’s one region of the world that’s well-positioned to grow and industrialize in the new era of geopolitical fragmentation. This is the region I call SASEA — an acronym for South Asia and Southeast Asia. South Asia includes India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, and some smaller countries nearby. Southeast Asia includes the big island countries of Indonesia and the Philippines, the medium-sized mainland countries of Vietnam, Thailand, and Myanmar, the small rich countries of Singapore and Malaysia, and a few others.

I coined this term — I pronounce it like “SAZ-ee-uh” — because no one else seemed like they were going to do it. The Economist briefly talked about “Altasia”, but the term never caught on, and it also included developed countries like Japan and Korea. SASEA is a much more cohesive bloc because it’s geographically contiguous, and most of it is still in the early stages of industrialization.

I’ve drawn the SASEA region in gold on the map above. I made a distinction between the “active” countries — those that seem like they could be good destinations for foreign investment and manufacturing-led growth — and those countries where war, economic dysfunction, or remote location makes them less likely to industrialize soon.

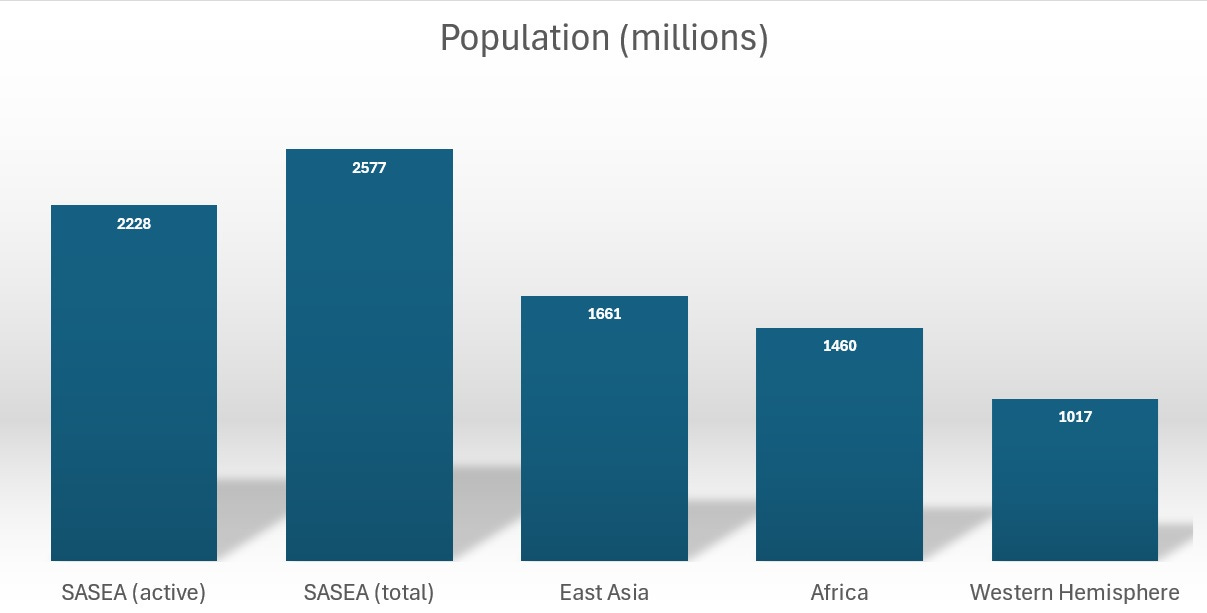

I don’t think people realize just how important SASEA is. It may not look big on a Mercator projection, but its population size is absolutely enormous; India alone is bigger than China now, and the region as a whole contains a full third of humanity. SASEA has far more people than Africa, East Asia (excluding Southeast Asia), or the entire Western hemisphere:

Even without India, SASEA would still be more populous than the entire Western hemisphere! In other words, SASEA is not some minor peripheral region of the globe. If it were one of the World Bank’s official regions, it would be the world’s largest.

And SASEA’s population is still relatively young. Although all of the region’s countries have experienced a fertility transition (like almost everywhere else on Earth), they did so later than most others, and so their populations are projected to remain much younger than China’s for the foreseeable future:

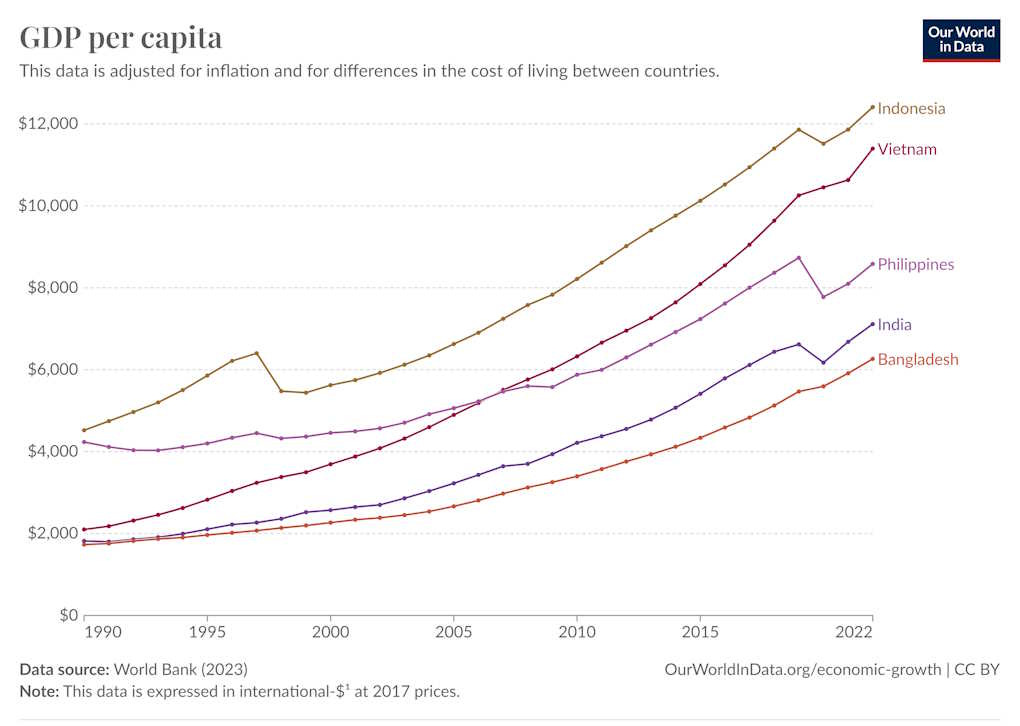

Nor is SASEA stagnant. Its largest countries are on a smooth upward growth trajectory, and while none of them are anywhere close to rich yet, all of them have escaped the World Bank’s “low income” category.

Just looking at pictures of the skylines of Mumbai, Jakarta, Manila, Ho Chi Minh City, or Dhaka will give you an idea of how dynamic the region is. Everyone has gotten used to being wowed by pictures of China’s urban skylines in recent years; I suggest looking at some of South and Southeast Asia’s.

And most of these countries are taking in lots of money — their net inflows of foreign direct investment as a percent of GDP have compared favorably to China’s since around 2016:

And the countries of SASEA are pretty export-oriented, with many of them exporting more of their GDP than China does:

Although India is famous for service exports and Indonesia for natural resource exports, manufactured goods actually make up a significant percent of their export mix. And for countries like Philippines, Bangladesh, and Vietnam, manufactured exports dominate. For example, here’s Philippines:

So the fundamentals are all there for SASEA to be the next big globalization story. It won’t be exactly what China was in the 2000s and 2010s, but it has the size, the youth, and the economic structure to be both a manufacturing export powerhouse and a massive gold rush for multinationals looking for the next profit opportunity.

Geopolitics favors SASEA in the 2020s and beyond

Most stories about globalization these days talk about the political headwinds — developed-country protectionism and Chinese subsidized overcapacity. But in fact, I think geopolitics will provide a huge boost to SASEA’s industrialization, for several reasons.

First of all, a lot of companies from Asia, Europe, and the Anglosphere are trying to de-risk from China. Everyone now knows that if there’s a big war between China and the U.S. — over Taiwan, the South China Sea, or whatever — their China operations are likely to be interdicted or even seized. In addition, the creeping assertion of government control over every facet of the Chinese economy under Xi Jinping, especially since the pandemic, has exerted a chilling effect on private business. As a result, companies are increasingly avoiding the country:

A measure of foreign direct investment in China declined for the 12th straight month, underscoring Beijing’s struggle to improve its appeal to overseas investors to boost growth…Inbound FDI in China dropped 28.2% in the first five months of 2024 from the same period last year to 412.51 billion yuan ($56.8 billion), according to data released by the Chinese Ministry of Commerce on Friday. The figure was worse than the 27.9% drop in April and extended a streak since June 2023.

Where are these companies going to put their factories and offices? Some will go back to developed countries, lured by the promise of automation. But many will go to SASEA. This is already happening. Even without bringing India or Bangladesh into the picture, Southeast Asia has already overtaken China as a destination for manufacturing FDI from the OECD:

Of course India is the most favored destination for U.S. companies, given its huge size, low wages, and the fact that it’s an unambiguously friendly country. U.S. FDI to India has actually slowed since 2021, but is still much higher than before the pandemic.

Tariffs on China will only add to that calculation. Countries around the world are starting to tax Chinese-made imports. That gives multinationals an incentive to make their wares elsewhere. Development economist Arvind Subramanian writes:

[T]oday’s tariffs are being imposed on imports from perceived adversaries like China, redirecting economic activity toward third-country suppliers considered allies…

India offers a prime example. It has successfully attracted several Western firms exiting China since launching its “China Plus One” strategy in 2014. Notably, Apple has significantly expanded its iPhone manufacturing operations in India, and Tesla reportedly may follow suit…If India can establish a supply chain that is largely independent of China – a trend that is slowly underway in the electronics sector – it could gain a competitive advantage over China and countries linked to it…

[T]he greater the overlap between America’s strategic interests and third countries’ capabilities and comparative advantages, the more likely that discriminatory protectionism will be long-lasting and provide certainty to investors seeking to diversify away from a ruthlessly efficient China.

But it’s not just Western companies that will invest in SASEA to avoid tariffs. Chinese companies will too. In recent years, Chinese manufacturing companies like BYD, Huawei, Xiaomi, CATL, DJI, and others have emerged as technological powerhouses in their own right. To compete in the global environment in the age of tariffs, and to look for new growth opportunities in the face of a slowing Chinese economy, they will go abroad:

Chinese carmakers and producers of other goods hit by tariffs announced by the Biden administration on Tuesday are expected to shift production to other countries to get around those penalties…Analysts say they foresee a shift to factories in Mexico, Vietnam or other parts of Southeast Asia, because of the tariffs, which were imposed to protect local manufacturing – notably automakers, but also other key sectors…Mexico and Vietnam, in particular, have benefitted from escalating US-China trade tensions due to their lower costs and proximity[.]

Even Chinese state media is now bragging about this strategy.

Vietnam is the primary beneficiary, but the more developed economies of Malaysia and Thailand are also important destinations for Chinese FDI:

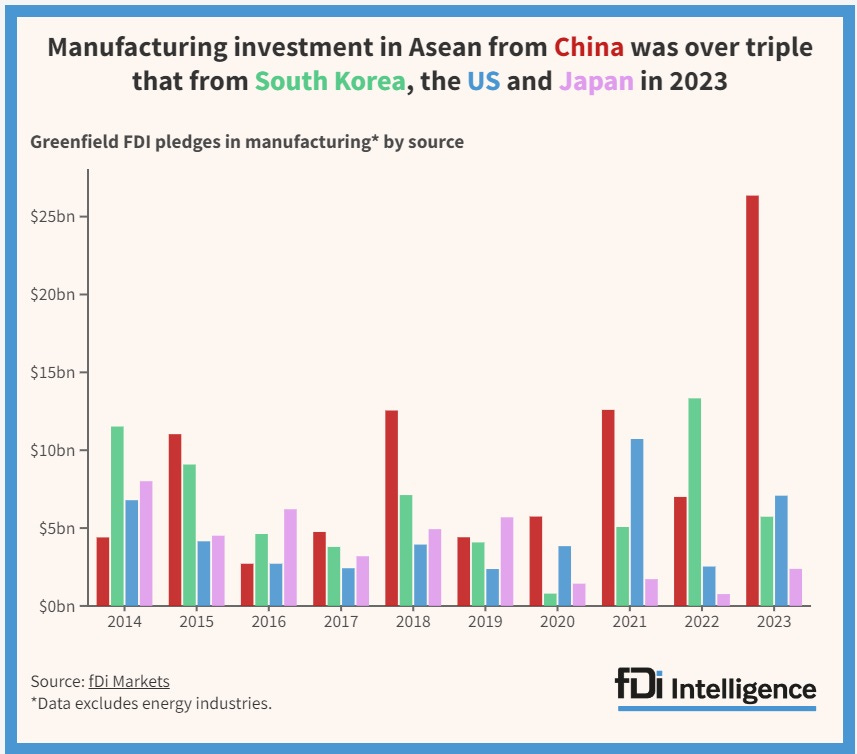

In fact, China is now out-investing the West in Southeast Asian manufacturing!

Battery manufacturing is an especially big part of this trend right now.

At first, Chinese companies will just use places like Vietnam as export processors — low-skilled labor to slap together Chinese-made components in the hope of avoiding the “Made in China” label that would subject the final assembled product to U.S. or European tariffs. But as time goes on, these Chinese firms will become more accustomed to producing abroad, and rising costs and slowing growth in China will give them a reason to move higher-value activities to SASEA as well.

For some countries, geopolitical competition will provide an extra push. Both the U.S. and China are intent on courting Vietnam and Indonesia as crucial “swing states” in their emerging regional competition. That should make it easy for those two countries — and possibly others — to court investment from both sides. Indonesia is already successfully pressuring China to invest in its local battery supply chain.

If SASEA countries are wise about it, they’ll be able to push China to transfer technology in exchange for market access — just as China did to companies from America, Europe, Korea, and so on. There have recently been good in-depth reports from the Observer Research Foundation and from Rest of World, detailing Chinese companies’ and workers’ anxieties about teaching India their manufacturing tricks. This is from ORF:

There is considerable online outrage in China about Chinese enterprises that have set up units in India…They are being called ‘traitors’ and ‘enemy collaborators’, who are jeopardising China’s national security for ‘petty gains’…Some prominent Chinese voices have joined the chorus. Senior editor Ding Gang recently wrote in People’s Daily that the Chinese government should establish policy measures to ensure that core technologies and talents remain within the country, restraining local manufacturers who may follow leading companies like Apple Inc., Xiaomi, and others in moving their production lines to India…Professor Chen Xin of the Shanghai Advanced School of Finance, Jiao Tong University, has gone further, demanding “systemic policies to prevent India from industrializing”. [101] He insisted China should not help India in building infrastructure or energy facilities, and should not sell industrial equipment to India.

Sound familiar? And this is from Rest of World:

Chinese engineers sometimes talked about how they were working to make their own jobs obsolete: One day, Indians might get so good at making iPhones that Apple and other global brands could do without Chinese workers. Three managers said some Chinese employees aren’t willing teachers because they see their Indian colleagues as competition. But Li said that progress was inevitable. “If we didn’t come here, someone else would,” he said. “This is the tide of history. No one will be able to stop it.”

So far, the profit motive seems to have won out over nationalistic sentiment. The governments of India and other SASEA countries are smart, they’ll encourage more tech and know-how transfer from China, in order to level up their own value-added.

To sum up, there’s now a strong case to be made that developed countries’ tariffs on China are now effectively pro-globalization. The Chinese government had been trying very hard to onshore all of China’s production — to turn China into the “make-everything country”. This, rather than any protectionist effort by other countries, has actually been the driving force of deglobalization (or “slowbalization”) since the financial crisis of 2008.

And China is so huge that it was sort of managing to pull it off. Home bias, both natural and government-driven, combined with the agglomeration effects of China’s vast internal domestic market to make most Chinese companies simply uninterested in offshoring production. The proverbial “flying geese” were failing to fly from China to the next location.

Tariffs on China, as well as other de-risking and friend-shoring policies, are thus providing a needed push to counteract China’s home bias and spread the blessings of industrialization to other countries that now need it more. Without developed countries’ de-risking and protectionism, SASEA might have had to wait for several more decades before cost pressures finally forced Chinese firms to invest abroad.

In other words, the very same forces that many pundits and economists now fear will reverse globalization actually have a good chance of accelerating it. The 2.5 billion people of SASEA need a ton of FDI and rapid industrialization, in order to escape poverty and join the ranks of the advanced nations before their populations follow the developed world into old age. Now, thanks in part to geopolitics, there’s a good chance they’ll get it.

My previous posts about SASEA

I also thought it would be useful to link back to some of the posts I wrote about industrialization in individual SASEA countries back in 2021 and 2022. Here are five important ones, with background on each country’s industrial policies, economic structure, and export performance:

SASEA really is globalization’s next frontier. The age of export-led industrialization is not finished — geopolitical tensions will not return us to a world of local supply chains, nor will China become the world’s single factory floor. Yes, it’s a time of tensions, competition, and fragmentation. But so was the first Cold War. And just as Japan, Korea, and Taiwan reaped the benefits of Cold War 1 when access to Western markets drove their industrialization, the billions of people living in South Asia and Southeast Asia are well-positioned to benefit from the new age of geopolitical rivalries.

I want to pronounce it like “sassy”

Very interesting write-up, thanks. Especially enjoyed the insight that tariffs could be pro-globalisation.