Can the Philippines sustain its growth?

The most important task for the new president.

The Philippines has just elected a new president, Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos, Jr., in a landslide. This has prompted much consternation abroad, as Marcos is the son a dictator who killed thousands and holds the Guinness World Record for the largest theft ($5-10 billion) from a government. So it’s understandable why people might be a little anxious.

But assuming the new Marcos doesn’t repeat his father’s tragic reign, there’s still the question of whether the Philippines can continue and extend its recent run of economic growth. It’s still a pretty poor country, but over the past two decades the Philippines has managed to double its living standards:

That’s not a spectacular run, but it’s very solid. What’s even more promising is how smooth and exponential this growth path has looked since 2000 (though of course I’ve omitted 2020, the Covid year, as I usually do on these graphs). An exponential growth curve suggests a self-reinforcing process — a virtuous cycle of growth. Those cycles never last forever, but they can fundamentally change the nature of a country before they peter out.

So what accounts for the Philippines’ recent success? The answer, basically, is that it’s following a close variant of the same old growth strategy that every successful country follows.

Electronics manufacturing, not remittances

When I write these development summary posts, the first question I always ask is what kind of an products a country exports. There are basically two types of countries here — natural resource exporters and exporters of manufactured goods. In general you’d much rather be the latter; countries that earn their wealth with sweat and ingenuity instead of by digging rocks up out of the ground tend to start off poorer, but have a much greater chance of getting rich in the end. So it’s encouraging to see that the Philippines is a manufacturer:

Now, if you’re an American, when you hear about the Philippines economy you don’t usually hear about electronics manufacturing. Instead, you hear about remittances — about Filipinos going to rich countries to work as nurses, nannies, sailors or flight attendants, and sending money back to their families in the Philippines. Remittances aren’t counted as an export in the chart above, but they are substantial — about $31.4 billion in 2021, over a third as large as the country’s actual exports.

The focus on remittances leads people to underrate the Philippines’ development potential. Remittances are good — they tend to reduce poverty and improve children’s health and educational outcomes. But research strongly suggests that remittances have little effect on economic growth — they don’t tend to get invested in domestic industry.

But the Philippines is growing, and it is investing in domestic manufacturing industries, including export industries. And ultimately this is a far more important story than the remittance story. A 2018 report by the Asian Development Bank writes:

[The Philippines’] potential growth is increasing. It reached 6.3% in 2017, the highest value during the last 60 years. We find that in recent years, labor productivity growth (technical progress) accounts for most of the country’s potential growth rate…A decomposition of labor productivity growth shows that the within effect accounts for 70% of it, and that most of it is due to manufacturing productivity growth.

(Side note: the ADB report notes that even though overall employment in manufacturing is increasing in the Philippines, manufacturing’s share of share of overall employment isn’t increasing, because workers are going into service jobs even faster. This is a change from the classic development model where farmers went into factories first and then services later, and it may reflect greater automation in manufacturing. But it seems fine; as long as you make a bunch of stuff and export it, you’re basically following the classic growth model. Manufacturing is 18% of the Philippines’ GDP, which is similar to growth star Vietnam.)

Note that the shift from agriculture to manufacturing — which has been accompanied by some of the world’s most rapid urbanization — was something a lot of development analysts were pretty pessimistic about just a few years ago. In his 2014 book How Asia Works, Joe Studwell spoke of the country in scathing terms:

The Philippines has no indigenous, value-added manufacturing capacity. At the end of the Second World War only Japan and Malaysia had higher incomes per capita in Asia. Then Korea and Taiwan overtook the Philippines in the 1950s. The country slid down past Thailand in the 1980s, and Indonesia more recently. From having been in a position near the top of the Asian pile, the Philippines today is an authentic, technology-less Third World state with poverty rates to match.

It’s not clear what Studwell meant by “indigenous manufacturing capacity”. But when a country has doubled its per capita GDP in two decades and its top export is integrated circuits, it’s really not right to think of it as a Third World country. It’s true that the Philippines’ growth languished for a long time, but Studwell’s characterization seems unfairly harsh, especially for 2014.

FDI, the flying geese, and the Southeast Asian supercluster

Let’s think about that word “indigenous”. Studwell, like his fellow development writer Ha-Joon Chang, generally believes that countries out to eschew foreign direct investment and try to develop their own native champions — the classic model here being South Korea with Samsung and Hyundai. Now, South Korea is certainly a star, but in recent years a number of countries have been getting pretty far using a more FDI-centric model. These include, most prominently, China, but also Poland and Malaysia. There’s a debate to be had about whether or not you can get all the way to a GDP of $50,000 without your own indigenous high-tech manufacturing companies, but getting to $30,000 is pretty damn good. Maybe it’s easier to just take the foreign investment, get to near-developed status, and worry about the last mile later.

In any case, around 2010 the Philippines appeared to shift to a more FDI-centric strategy, boosting annual inflows from around $1 billion to about $8-10 billion. That’s still a fairly modest sum, but it could go up even more. Outgoing President Rodrigo Duterte recently amended foreign investment rules to make FDI much easier. The top investors are China, Singapore, Japan, and the U.S.

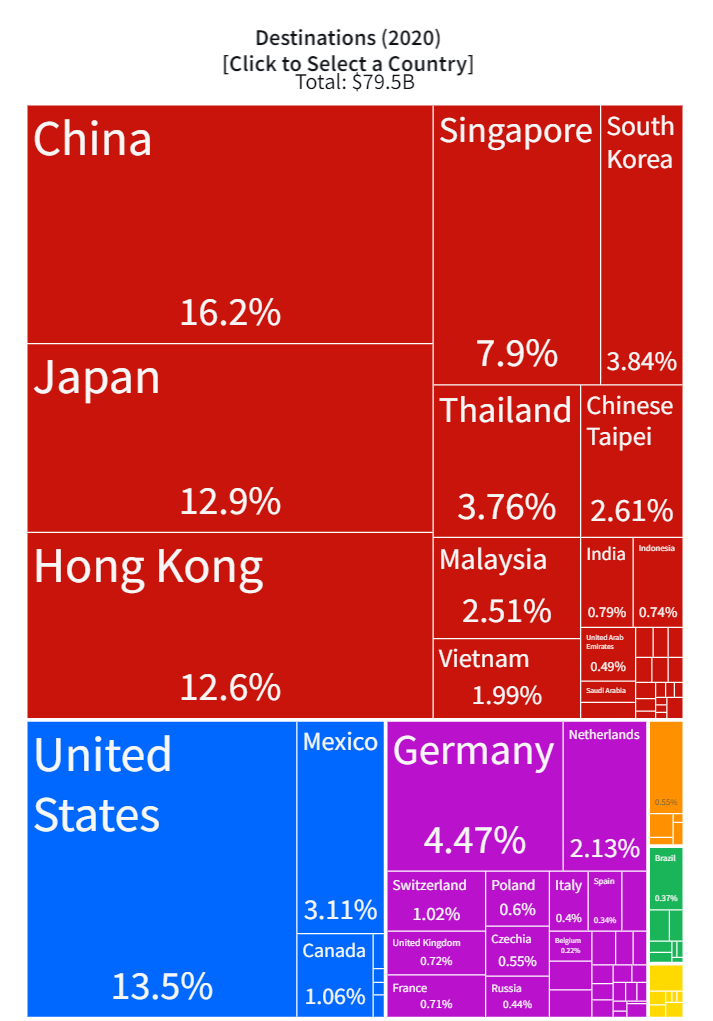

But even aside from FDI, the Philippines has been doing a lot of subcontracting work, making stuff for companies in richer Asian countries (and the U.S.). These are the main destinations for the Philippines’ exports:

Together, FDI and subcontracting from higher-cost neighbors demonstrate a phenomenon known as the flying geese theory — the idea that manufacturers move from country to country as each one goes from low-cost to high-cost, leaving economic development in their wake.

In other words, though the Philippines has certainly done some good industrial policies — building a ton of infrastructure, boosting secondary education, making FDI easier, and so on — ultimately the growth might not have been possible without the influence of the Asian electronics manufacturing supercluster.

In fact, if we zoom out and look at growth for all the countries in the region, we see that everyone is growing, and most are on smooth exponential paths:

In other words, Southeast Asia is growing together, and a big reason is just economic agglomeration — the spillover from the mighty East Asian supercluster making its way throughout the region.

So what does the incoming President Marcos have to do in order to sustain and accelerate the Philippines’ run of growth? Well, of course do the obvious — keep boosting education and infrastructure and encouraging investment and exports. But really, those are all less important than one thing: Political stability.

If the Philippines’ growth is being powered by regional agglomeration and flying geese, then really the only big threat to growth is instability. Thailand and Myanmar, despite having great growth records for a while, have both recently been stalled by instability. Brutal crackdowns against widespread protests have made both countries far less attractive as destinations for investment or sources for manufactured goods.

So for Marcos to keep his country’s growth going, and keep living standards rising for his people, the most important task is to avoid repeating his father’s mistakes. Peace, tolerance, low corruption, and rule of law will prevent the country from spiraling into chaos.

Question - where do you get these Exports and Destinations data from? (Not questioning data--I like the charts)

"It is a soft, forgiving culture. Only in the Philippines could a leader like Ferdinand Marcos, who pillaged his country for over 20 years, still be considered for a national burial. Insignificant amounts of the loot have been recovered, yet his wife and children were allowed to return and engage in politics."

— Lee Kuan Yew