Vietnam: It's time to level up

Economic reforms led to a burst of spectacular growth, but the country needs a lot more if it wants to get rich.

I’ve been writing a series of posts focusing on various countries’ economic development, generally trying to apply the lens of the “industrialist” theory of development — the framework laid out by Ha-Joon Chang, Joe Studwell, and a few others. Today I thought I’d cover another successful case: Vietnam.

Vietnam is, by almost any stretch of the imagination, a development success story. Since 1990 — roughly the year when the developing world started catching up with the developed world — Vietnam has approximately quintupled its living standards, performing better in percentage terms than practically any other country in Southeast or South Asia:

Note the smoothness of that growth curve; the Asian financial crisis of 1997 that hit so many other regional economies so hard barely caused Vietnam to stumble.

But this stellar percentage performance masks the fact that in absolute terms, Vietnam is still pretty poor. As of 2019 it had basically caught up with the Philippines, but was far behind Thailand and Malaysia.

In other words, Vietnam’s stellar performance over the past three decades simply allowed it to climb out of a deep hole of utter poverty. Essentially, Vietnam has completed Level 1 of development, and it’s time to move on to Level 2.

First, let’s review how Vietnam got to where it is, and then think about where it needs to go from here.

The success story: Liberalization, FDI, and light manufacturing

In the 1980s, Vietnam reformed its economy, transitioning gradually away from the failed Soviet-style central planning of the 70s. Here’s a good overview of those reforms by McCaig and Pavcnik. Most of the changes were just privatization of one sort or another — first allowing farmers to sell their land, then allowing private enterprise in a range of sectors, then privatizing some state-owned enterprises in the 2000s. The government also opened up the country to foreign investment, and created a bunch of incentives for foreign companies to invest there. Both of these policies were very effective. The country started producing a lot more food and commodities, and foreign investment flooded in. People don’t realize this, but Vietnam’s economy is more FDI-intensive than China’s or Malaysia’s:

Now, note that this is something Ha-Joon Chang says not to do. Chang sees FDI as a trap — if you make a bunch of stuff for foreign companies, he argues, they won’t give up their best technologies and they’ll end up crowding out domestic companies that could become high-tech national champions and internationally recognized brands. I’m not sure he’s right about this in all cases, but let’s table that discussion for now.

So anyway, what sectors did the foreign investment flow into? Most of it went into manufacturing, and most of that went into the electronics and apparel industries. Those are now Vietnam’s main export sectors:

If you’re a poor country, electronics and apparel are very good sectors for pumping up exports very quickly. They’re light, so they’re easy to ship (unlike say, cars or steel). They’re labor-intensive, so if you’re a poor country with cheap wages, you’ll be very competitive in these industries. And electronics is especially good for moving up the value chain, because once all the phone assembly factories are located in a particular place, it makes economic sense to start manufacturing some of the components there too, and so on.

It’s especially good to make electronics if you’re in East Asia, which has become the world’s electronics supercluster. Vietnam’s main investors are just the rich countries nearby — Japan, South Korea, Singapore, Taiwan, and China (largely via Hong Kong). Samsung, for example, assembles a majority of its phones in Vietnam. The country is a poster child for the “flying geese theory” of development — basically, development appears to be spreading throughout Asia from country to country as electronics companies look for cheaper places to make stuff. Vietnam is really following in the footsteps of Malaysia in this regard.

In any case, FDI is what allowed Vietnam to accomplish the most important goal of early industrialization: structural change. Undeveloped countries mostly do farming; if you want to become a manufacturing powerhouse, the first order of business is to change this. Here’s what the transition looked like for Vietnam:

Structural change increases productivity. In a poor country, most of the people on farms aren’t really working efficiently, so just putting them in factories boosts GDP a lot. Urbanization also boosts GDP in general, though many people who move to cities end up working in services. And manufacturing tends to have faster productivity growth than other sectors in general, so having it be a larger slice of your economy speeds up overall growth.

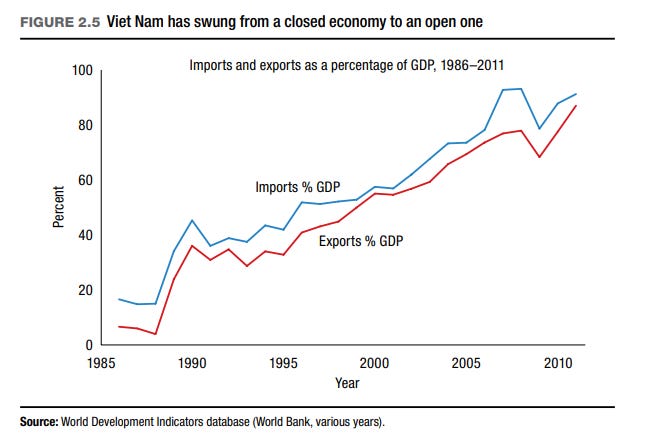

Manufactured products are also easier to export. Chang and Studwell both emphasize the importance of exporting in raising domestic productivity, both because it forces domestic companies to compete in challenging world markets, and because it makes it easier to absorb foreign technologies. (Note that this is about total (gross) exports, not net exports; this is not a mercantilist theory that trade surpluses = “winning”.) Vietnam’s apparel and electronics industries succeeded in pumping up exports, even though its trade was very balanced:

In other words, both Vietnam’s liberalizing reforms and its encouragement of FDI paid off. Labor productivity growth grew very rapidly in the 90s and 00s:

It’s a stunning success for a country that was one of the world’s poorest just three decades ago. And it seems like a “neoliberal” success, too — allowing private business and foreign investment doesn’t have much of the “industrialist” flavor of the stuff Chang and Studwell recommend.

But there are signs that this success story is beginning to run out of steam.

A slowing transition

Vietnam is still very far from the technological frontier. It should be able to grow its productivity substantially, simply by learning foreign technologies and by reallocating labor from agriculture to manufacturing. But in recent years, total factor productivity growth has made only a modest contribution to GDP.

This would be a respectable rate of TFP growth for a rich country, but for a poor country it’s just not good enough to sustain rapid catch-up growth. Without accelerating productivity, Vietnam’s growth will eventually stagnate.

Part of slowing productivity growth is a slowdown in structural transformation — the shift from agriculture to manufacturing. Tu-Anh Vu-Thanh has a very sobering 2017 book chapter in which he showed that this transition was already slowing by the late 2000s:

However, after nearly three decades of extensive development, Viet Nam’s industry now seems to have reached a ‘glass ceiling’. The rate at which labour moved out of agriculture during the period 2006–12 was less than a third of the rate during 2000–6. In the last five years, the manufacturing value-added (MVA) growth rate has significantly declined to 7.5 per cent from 12.2 per cent in the previous period. In 2012, MVA accounted for only 17.4 per cent in the gross industrial value compared with 36 per cent in the early 2000s. The proximate causes of this stagnation are that Viet Nam has been caught in the ‘low value added trap’ with shallow integration into the global value chain and declining productivity.

And as you can see from the chart in the previous section, manufacturing has increased, but only to around 20% of GDP. Agriculture still takes up 60%, compared to around 2% in South Korea. The structural transformation is not proceeding rapidly enough.

Basically, the 1980s economic reforms that did so much good have begun to run out of steam. To revive growth, Vietnam needs new policies. There are a number of ideas for what those policies should be, from the fairly obvious to the speculative and experimental.

Low-hanging fruit: Higher education, urbanization, infrastructure and friend-shoring

One very obvious thing Vietnam can do to boost productivity is just to send more of its young people to college. Vietnam has very good K-12 education, but almost everyone stops after high school; as a result, the country has one of the lowest higher education rates in the region.

Not being able to find skilled engineers and managers is one of companies’ largest complaints about Vietnam. College helps fix this. The economist Khoa Vu has a recent paper, co-authored with Vu-Thanh, that finds large and positive effects from boosting higher ed. From the abstract:

We study…a national expansion of higher education in Vietnam, which established over 100 universities from2006 to 2013. Collecting a dataset on the timing and location of university openings, we estimate that individual’s exposure to a university opening…raises their wage by 3.9%…At the market level, the expansion increases the relative supply of college-educated workers…[F]irms…raise productivity and hire more college-educated workers. We also find that opening a university in one district has substantial spatial spillover effects on to the labor market of nearby districts.

So build more universities, send more kids to college. And those universities will also help the country further down the line, when it comes time to start doing more research.

A second policy is just to continue moving people off of the farms and into the cities. Urbanization in Vietnam is still only around 40%, compared to about 65% in China and 81% in South Korea. Vietnam has not yet hit its “Lewis turning point”; there are still plenty of poor Vietnamese people to move off the farm and into the factories.

The danger of this is that you’ll get “consumption cities” where people mostly work in low-value services instead of factories. This has been the pattern in resource-based economies in much of Africa, the Middle East, and Latin America. This kind of urbanization is still better than remaining rural, but it’s not nearly as good as when urbanization is part of structural transformation.

A third piece of low-hanging fruit is building better infrastructure. The World Bank reports that Vietnam has built a lot, but has two main problems: 1) it doesn’t have very good water infrastructure, and 2) it doesn’t maintain its roads. Spending more on these should be a no-brainer, because both good water management and good roads are very important for doing high-quality manufacturing and building functional cities.

The last no-brainer policy, which Vietnam is already doing very enthusiastically, is just to take advantage of rich countries’ desire to decouple their supply chains from China. Vietnam already benefitted from the U.S.-China trade war before the pandemic (though some of this was Chinese companies evading tariffs by moving products through Vietnam). Now export controls and worsening U.S.-China relations in general are causing companies like Apple to diversify into Vietnam and India.

Vietnam’s government can encourage this shift by using special economic zones (which may or may not be very different from what it calls Free Trade Zones). SEZs use financial incentives and high-quality local infrastructure to lure foreign manufacturers and concentrate them in specific regions, and have generally proven an effective tool for developing countries.

So those are a bunch of fairly obvious policies that are generally easy to execute. But it’s likely that the easy stuff alone won’t take Vietnam as far this time as it did in the first round of reforms. The government should also experiment with ways to increase its companies’ productivity and return on investment.

The hard stuff: SOE reform and export discipline

In his 2017 overview, Tu-Anh Vu-Thanh, the problem is political. He argues that state-owned enterprises are getting favorable treatment over private ones, due to a combination of political cronyism and lingering communist ideology. Vu-Thanh details various ways in which SOEs get preferential access to resources, and argues that this is starving domestic private companies of the capital and labor they need to grow. This could help address the problem that most of the private businesses in Vietnam are small household enterprises that perform services for the domestic market.

A friend, describing life in Ho Chi Minh City, once told me that “everyone owns their own restaurant.” The statistics support that basic picture.

SOEs themselves probably do use their resources very inefficiently. A 2019 paper by Baccini, Impulliti, and Malesky studied Vietnam’s WTO accession in 2007, and found that when exposed to international competition, private companies either got competed out of the market or stayed in the game by raising their productivity — exactly the kind of beneficial effect that Chang and Studwell would predict from exporting. But SOEs were basically unaffected, suggesting that government policy protects them from competition. Baccini et al. conclude that “overall productivity gains [from joining the WTO] would have been about 40% larger in a counterfactual Vietnamese economy without SOEs.”

So one possible approach for Vietnam is to simply privatize more SOEs and remove the supports they get from the government. But a 2020 paper by Dang, Nguyen, and Taghizadeh-Hesary shows that the country actually has made considerable ongoing progress in privatizing SOEs. and that doing more of this will be difficult while private capital is scarce and the stock market isn’t well-developed. In fact, Vu-Thanh’s statistics show that SOEs in Vietnam accounted for only 39% of investment by 2011-13 — a large number, but lower than China’s share in the 2000s after several well-known rounds of vigorous SOE privatization in that country. In other words, there may just not be much to do on the privatization front right now.

Other approaches to the SOE problem involve removing the preferential treatment Vu-Thanh describes, and pushing SOEs toward greater productivity with various reforms in how they’re managed. That all sounds good, though it’ll probably be politically difficult. But beyond those hard reforms, I think the most important thing Vietnam needs to do is simply to promote more exports — both by SOEs and by domestic private companies.

Export promotion — specifically, something called export discipline — is the basic recommendation of the Chang-Studwell development thesis. Basically, the idea is that exporting forces companies to compete in highly competitive global markets instead of staying home in the cosseted and safe domestic market. This pushes companies to be their best selves, and it also causes inefficient companies to shrink and die while efficient ones expand and grow. And exporting puts domestic companies in touch with foreign buyers, suppliers, and (most importantly) workers, which helps them to absorb all-important foreign technology.

McCaig and Pavcnik have a 2018 paper where they show the value of exports for Vietnamese productivity growth. They find that the United States-Vietnam Bilateral Trade Agreement in 2000 led to a shift in employment toward manufacturing in the formal sector, as well as productivity gains.

Export discipline is a very specific procedure for achieving these gains. First, you give your domestic companies very strong incentives to try to sell more in foreign markets (in South Korea, dictator Park Chung-hee would even throw business execs in jail for a few nights if they didn’t try to export!). At the same time, you give companies financial and logistical support for their exporting activities — but only for a little while. If a company succeeds in global markets, you withdraw government assistance, because the company no longer needs it; if the company fails to export, you withdraw assistance and allow the company to fail, thus freeing up resources for better companies.

Vietnam can use this approach with both SOEs and domestic private companies. It will incidentally solve the resource allocation problem, because capital and talent will flow to whoever does best at exporting. Small companies will be able to scale up more effectively. Export discipline will also help alleviate the FDI problem — most of Vietnam’s exports are now done by foreign companies, which, as Ha-Joon Chang notes, are less eager to transfer foreign technology into the country.

Anyway, Vietnam since 1990 has been a solid development success story, but it’s still in the early days of the process. I’m really rooting for the country to succeed — if the government is willing to take the right steps, Vietnam could be the next Malaysia, or even, someday, the next South Korea. What a triumph that would be.

Some assorted notes from Vietnam:

Channeling Matt Yyglesias: housing is the cause of all problems. It is hard to overstate how insanely expensive housing is in any capital city. Which is obviously going to affect urbanization. You have to get pretty far out in the suburbs to get anything reasonably priced but the infrastructure isn't there to support those kind of commutes. It's honestly a bit of a mystery to me because Vietnam lacks the usual culprits of zoning and NIMBYs that plague housing in the West. But there's a massive, massive shortfall in affordable housing.

Education might look good on paper but the reality often falls short. Classrooms are woefully understaffed -- 40 students is common. Teachers are underpaid -- they often offer "mandatory" tutoring on the weekends to make extra money. And the education system is very much geared towards memorization and obedience, which might make good factory workers but isn't great for the 21st century knowledge economy. I've hired a lot of uni graduates and a Vietnamese university graduate is generally less competent than an Australian university junior doing an internship.

Corruption and fraud continue to be very widespread. There's a current crackdown on corruption, which is needed. But it has a side effect of every government official being terrified of actually DOING anything right now, with even more projects than normal being mired with no progress.

The entire economic system has rife with fraud -- the FLC chairman was recently arrested for stock market manipulation, the Vin Thinh Phat chairwoman was arrested for fraud, 40,000 customers of banks were fraudulently sold bonds of Tan Hoang Minh Group...and that's just from the past few weeks. FDI is down 10% from 2021 due to reduced investor confidence.

Demographics are a challenge. Vietnam is aging quickly but doesn't have the social safety net to weather it well. Migrant workers are often locked out of subsidised childcare due to Vietnam's version of China's "hukou" household registration system. Traditional marriage has tons of downsides for women, so more and more are opting out.

There's still a fair amount of regional factionalism between north and south. No southerner has ever been General Secretary of the Party and only 2 of 12 Prime Ministers have been from the south. A constant complaint from the Ho Chi Minh City government is that a lot of the revenue they generate is distributed to other provinces rather than reinvested back into the city.

Then on top of all these challenges add the problems facing the Mekong. Upstream dams (Chinese built), salinity-issues, land sinking, rising sea levels. It feeds half the country.

All of these challenges are surmountable but as Tomas VdB says, decision making is amazingly poor for such a (theoretically) centralized political system, apparently riven by endless backdoor factionalisim that only insiders have any real clue about. One very common example, for instance, is that some development project -- a new bridge, for instance -- is delayed for years because one government department (usually the army or navy) refused to hand over the land to another government department so the construction can proceed. The Thu Thiem Bridge 2 was officially commenced in 2015, scheduled for completion in 2018, but didn't actually open 2022. And that's in the heart of Ho Chi Minh City and was a major contributor to traffic woes for over half a decade.

Despite how it might sound, I'm actually very bullish on Vietnam. Despite all those issues it is clearly better positioned than other places in Asia. Yes, it has bad demographics. But China, South Korea, Singapore, and Japan are worse. Yes, it's low-lying nature makes it vulnerable to rising sea levels. (Take a look at projections of how much of Ho Chi Minh City will be under seawater by 2050!) But those issues, and others, aren't insoluble.

But it means Vietnam can't coast on easy wins like it has for the past 50 years. France was almost comically bad at running colonies (not just in Vietnam), so a lot of economic gain was just "catch up" from doing bare minimum stuff like increasing literacy from 5% to 99% and land reform.

On a side note, there's been a notable increase in the number of Filipinos coming to Vietnam for work. Who would have predicted that even just 5 years ago?

Having lived in VN for over 2 years (2019-2022) and witnessed government policy making first hand, I must say I am a lot less positive about Vietnam’s future than I was before.

The main reason is that decision making at all government levels seems virtually non existent. Unlike China, which has a very strong central leadership, Vietnam’s government is very fractious , with an enormous amount of infighting and score-settling all the time.

This means no one want to be accountable for decisions in case they will be used against them at a later stage.

There is also an enormous amount of rent seeking, where one group may oppose very sensible policies or development projects just in order to extract financial gain. For a communist country, Vietnamese are extraordinarily obsessed with money, and rent seeking is the quickest way for (local) officials to get rich.

Combine this with all the other factors, such as the poor education and lack of political vision, and you have a country that’s heading for a grinding halt.

Yes, some big manufacturers are still settling up factories, and these are hailed as big victories, but these are just riding on past policies. “Changing direction” is not something I think Vietnam is able to do.

The former Singaporean PM Lee Kuan Yew, already described Vietnam’s problems in his memoirs, and they haven’t been fixed. If anything they’ve gotten worse because there is so much more richness up for grabs.