Do poor countries need a new development strategy?

Bangladesh and Southeast Asia are defying the economists who say industrialization is dead.

Back in the 1990s and 2000s, the debate over development had pretty clear battle lines. On one hand you had the neoliberals, who thought that free trade, low regulation, prudent macroeconomics, and good health care and education were pretty much all you needed. On the other hand you had the industrialists, who thought that the key was to emulate South Korea, and pursue an industrial policy oriented around exporting manufactured goods. The latter camp was smaller, and included folks like Alice Amsden, Ha-Joon Chang, and Joe Studwell.

Interestingly, China’s rapid industrialization didn’t really settle the argument — its early successes were mostly due to neoliberal reforms, but it rolled out a bunch of industrial policies starting in the late 2000s. It’s still an open question as to how important — and how reliable, and how easy — export-oriented industrial policies are. Personally, I think the industrialists are on to something, and in 2021-22 I wrote a series of posts looking at various countries’ development experiences through the lens of industrialist ideas:

The most spectacular success stories — Poland, Malaysia, and a few others — all seemed to broadly fit the South Korean model (though like China, they used more foreign direct investment than Korea did). So I’m pretty bullish on the whole export-manufacturing strategy.

Anyway, the industrialist camp also included the eminent Harvard economist Dani Rodrik. In 2004, Rodrik wrote a paper called “Industrial Policy for the Twenty-First Century”, urging countries to promote exports as a way of discovering their comparative advantages. In 2007, he wrote a qualified defense of the “import substitution industrialization” strategies that developing countries had tried in the 1960s and 70s. And in 2013, he noted that countries’ manufacturing industries tend to catch up to the global productivity frontier much faster than other industries; that suggests that developing countries can encourage productivity growth by increasing the size of their globally competitive manufacturing sector.

But in the middle of the 2010s, Rodrik began to have doubts. In 2015, he wrote a paper called “Premature Deindustrialization”, in which he argued that “countries are running out of industrialization opportunities sooner and at much lower levels of income compared to the experience of early industrializers”. He argues that as far as developing countries are concerned, automation isn’t the culprit; instead, it’s the global pattern of trade:

The obvious alternative [explanation, as opposed to technology,] is trade and globalization. A plausible story would be the following. As developing countries opened up to trade, their manufacturing sectors were hit by a double shock. Those without a strong comparative advantage in manufacturing became net importers of manufacturing, reversing a long process of import-substitution. In addition, developing countries “imported” deindustrialization from the advanced countries…This account is consistent with the strong reduction in both employment and output shares in developing countries (especially those that do not specialize in manufactures). It also helps account for the fact that Asian countries, with a comparative advantage in manufactures, have been spared the same trends.

Basically, Rodrik’s story for why Africa and Latin America have de-industrialized since the 1960s is twofold:

Asia’s industrialization sucked up most of the rich world’s the demand for manufacturing, leaving less for Africa and Latin America.

People in rich countries started to buy more services, and their demand for physical goods stalled out, meaning less global demand for manufactured products overall.

If this is true, does it mean that Africa and Latin America won’t be able to industrialize the same way other countries did? Maybe, but I have my doubts.

Most importantly, the first of the two effects above should be temporary. Once China and other Asian countries develop, they will become a big source of demand for manufactured products, just as Europe, the U.S., Japan, Korea, etc. all did. And their costs will rise, meaning they will go looking to buy stuff from cheaper places. After Asia is done developing, Africa will be the only region with low costs.

Also, Rodrik’s model suggests that premature deindustrialization causes manufacturing’s share of employment to peak at 18.9% instead of 21.5%. And it suggests that manufacturing’s share of output will now peak at ~$22,000 in 2015 dollars (~$29,000 in today’s dollars):

If manufacturing-led growth can take you all the way to $29,000 of per capita GDP — richer than Argentina is now — then I call that a win. Especially for places like South Asia, whose per capita GDP is currently ~$6,300, or Sub-Saharan Africa, which is at $3,700. And if manufacturing can put 19% of your population to work instead of 22%, well, that’s not too terrible either.

So when this paper came out, I wasn’t too worried. At worst, it made me only a tiny bit less optimistic about the industrialist approach to development.

But recently, Rodrik teamed up with the legendary Joseph Stiglitz to advance a much stronger — and much more pessimistic — version of the deindustrialization thesis. In a recent essay entitled “A New Growth Strategy for Developing Nations”, Rodrik and Stiglitz write that poor countries need to focus not on manufacturing, or even on exports at all, but rather on green energy and non-traded services:

[T]echnological changes have made manufacturing skill- and capital-intensive, and less and less labor-absorbing. This undercut the efficacy of industrialization as a growth strategy…The ability of the growth strategy to absorb labor was reduced at the same time as the comparative advantage of developing countries was at least attenuated…

Geopolitical competition between the U.S. and China and the creeping backlash against hyper-globalization transformed the global economic landscape and rendered the world economy less hospitable to growth through trade. As incomes in the developed countries increased, there was a shift [in demand] away from manufactured goods to services, so the share of global output in manufacturing was in decline. The impending climate-change crisis…reduced global demand for material goods, especially those with a high carbon footprint, as opposed to services…further disadvantaging developing countries…

While manufacturing will remain an important sector for most countries, we do not believe it can be the protagonist of economic growth in the way it was in East Asia and other successful economies of the past…[T]he export-oriented industrialization strategies of the past [will now be] less viable and effective. We have argued in this essay for a strategy with two key prongs: investment in the green transition and productivity enhancement in labor-absorbing, mostly non-traded services.

Stiglitz has been making arguments like this for a while. But for Rodrik, the new essay represents two important evolutions beyond his 2015 paper.

First, in his 2015 paper, Rodrik wrote that “Asian countries and manufactures exporters have been largely insulated from those [deindustrialization] trends”. But in their recent essay, Rodrik and Stiglitz argue that industrialization only works for East Asia. It’s not clear whether they include Southeast Asia in their definition. But in any case, whereas Rodrik (2015) exempted South Asia — a region of 1.92 billion people — from his hypotheses about premature deindustrialization, Rodrik and Stiglitz (2024) don’t think that India, Bangladesh, and so on can pull off anything similar to what China pulled off.

Second, in his 2015 paper, Rodrik argued that technology — meaning automated manufacturing — is only a cause of deindustrialization in rich countries, not in poor countries. The reason was that since poor countries have small economies compared to rich ones, automated manufacturing just allows them to sell even more stuff to rich countries, resulting in more factory employment despite automation.

That argument was always a bit questionable; India and Indonesia, for example, have very large domestic markets, despite still being nowhere near developed income levels. But in any case, Rodrik and Stiglitz (2024) appear to have completely discarded the argument of Rodrik (2015); they now argue that automation will be a force for deindustrialization in poor countries as well as rich ones.

Personally, I think both of these new arguments could use some stronger justification. I would like to know why Rodrik and Stiglitz believe that India is fundamentally incapable of pulling off anything close to what China pulled off. And I would like to know why they believe that automation of manufacturing will limit poor countries’ industrialization prospects more than it did in, say, the 1980s.

Another fundamental problem I have with this paper is that it conflates two very different objectives of economic development — growth and employment. Rodrik and Stiglitz argue at length that manufacturing won’t be capable of employing very many people in poor countries going forward. But that is very different than arguing that manufacturing will be less important for raising living standards.

Just as an illustration, consider the U.S. in the 1990s. Manufacturing’s share of GDP rose slightly, while its share of employment went down by almost a quarter compared to 1987:

This difference was due to automation. Automation allows you to produce the same amount with fewer workers — it’s exactly what allows manufacturing’s contribution to GDP to decouple from its contribution to employment.

So while automation of manufacturing might make it less of a job creator for countries like India, it’s a huge jump to conclude that it’s therefore unimportant to the economy. It’s possible that robotic factories, tended by a few engineers, will be an important source of revenue generation for developing countries. That revenue will then be spread around locally via local multiplier effects — the people who work at and who own the factories will spend their earnings locally, and each manufacturing job will create some larger number of other jobs in exactly the kind of nontradable services that Rodrik and Stiglitz want. That is exactly how it happens in America today, and it’s difficult to see why India wouldn’t work the same.

Now, there are a couple of difficulties with this. One is inequality. If automation leads to a few smart engineers making all the money and everyone else being poor, it’ll require radical redistribution policies to spread around the fruits of economic growth. But this is just as true for rich countries as for poor ones. And Latin America’s progress against inequality should give us hope that we can handle whatever automation throws at us.

A subtler problem is learning. Productivity growth comes from learning new technologies and new business models. In a world where factories employ very few people, those factories won’t be as useful as schools for workers. Factory work might serve an important role in teaching a whole population how to work hard, show up on time, manage a modern workplace, and so on — skills that might also come in handy in the service sector. In fact, Ha-Joon Chang believes this is a key reason why manufacturing is key. So without labor-intensive manufacturing, countries might need to come up with other ways of teaching their people to be more industrious.

But I think these are secondary concerns. While Rodrik and Stiglitz have a point about manufacturing employment, raising living standards is ultimately far more important than giving everyone something to do.

My final criticism of Rodrik and Stiglitz’ paper is that it tosses out something tried-and-true in favor of something speculative and poorly specified. Rodrik and Stiglitz talk in very general terms about things like “strategic dialogue”, “policy coordination”, and “institutions” to support a new kind of industrial policy focused on nontradable services. But the picture is very vague. In contrast, promoting manufactured exports is something that countries have a pretty good idea of how to do by now.

And if we look at the countries that are developing rapidly at this very moment, we see them following a fairly traditional strategy of industrialization. Vietnam is a good example, but my favorite example is Bangladesh.

Over the past few decades, Bangladesh has had one of the smoothest growth paths of any country. It is still poor, and it hasn’t grown as fast as China, but it has tripled its per capita GDP since 1995, making big strides against absolute poverty in the process:

And despite not being in East Asia, it has accomplished this feat using the kind of structural transition toward manufacturing that Rodrik and Stiglitz claim will be impossible going forward:

This isn’t quite an economic “miracle” yet, but if it goes on for much longer, it will be.

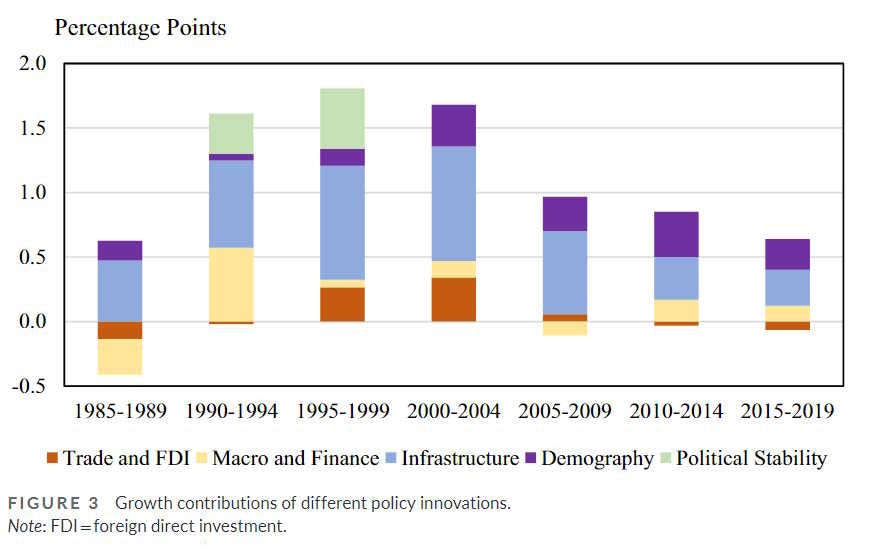

How did Bangladesh pull this off? I gave a lot of credit to the country’s industrial policy when I blogged about it back in 2021, but Beyer and Wacker (2023) have a much more systematic approach. They conclude that Bangladesh made “good enough” policy across a wide variety of areas:

Bangladesh encouraged FDI, built a bunch of infrastructure, maintained political and macroeconomic stability, stayed open to trade, and so on. Pretty traditional stuff. But Beyer and Wacker admit that this can’t explain everything about Bangladesh’s outperformance. There’s a big “residual” in their growth accounting framework. And Bangladesh’s last major policy reforms were decades ago; most countries would have slowed down by now, but Bangladesh has not.

One missing piece of the puzzle might be industrial policy — of the traditional “picking winners” type. A 2016 report by the Asian Development Bank explains how Bangladesh promoted the garment industry:

This transformation through garment exports did not occur in a vacuum: the government decided very early on to promote the sector and to provide incentives to get it where it needed to be…In addition to [Special Economic Zones to encourage foreign investment], a series of policies and external factors over the years contributed to the stellar performance of [garment] exports…The Multi-Fiber Arrangement, which allowed Bangladesh to import quota-free until 2005, provided the initial impetus…The policy of creating a special bonded warehouse system designated [garments] as a “100% export-oriented” industry and created a duty-free environment for the sector even though huge tariff and non-tariff barriers affected the rest of the economy. Moreover, effective taxation of earnings from [garments] was very low and income from [garment] enterprises is exempt from taxes.

Once again, a successful development story will leave neoliberals and industrialists debating which policy had the greater effect.

But whatever its secret sauce, Bangladesh presents a stern challenge to the Rodrik-Stiglitz thesis that the days of industrialization are done. Whatever their new nontradable-services-based industrial policy ends up being, it had better be able to deliver better sustained growth than Bangladesh. Right now, not a lot of countries are clearing that bar.

In fact, Bangladesh is embedded in a larger mega-region — South and Southeast Asia, together home to 2.4 billion people — that is seeing rapid, broadly distributed growth and pockets of intense industrialization. This, I believe, is the most important development story of our time. Perhaps Africa’s turn will come a bit later, but South and Southeast Asia are ready now, and 2.4 billion people is a very large number.

In my opinion, to tell these countries to give up on industrialization right now, at the cusp of their big moment, and to refocus on nontradable services instead, would be to do them a deep disservice. Instead, I think they should keep trying the traditional model of development, taking advantage of trends like friend-shoring and de-risking to encourage FDI and build up their manufacturing sectors. If that model eventually breaks, then it breaks, and we find something else. But from where I’m sitting, it doesn’t look broken yet.

Great article Noah. Some questions.

1. Based on the book "How Asia works" isn't it clear that most of Africa should focus a lot more on increasing agricultural productivity until they are more-or-less self sufficient? That would allow them to expand their foreign currency earning portfolio besides mining ores or fossil fuels (if the country has them), increase national savings from farmers, and stop using up foreign exchange to artificially prop up their currency to import food? It appears having a base level of food and fuel self-sufficiency is a baseline for a country to pursue export led growth. You can't expect a poor country that depends on cheap food and energy imports, to depreciate its currency for manufacturing exports when that policy would make food imports dramatically more expensive.

Most of Africa is in the 1.75 tons of food per hectare. Kenya a relative "star" of Sub-Saharan Africa is even lower at 1.49, Ethiopia is one of the few Sub-Saharan African countries that massively boosted food fields from less than 1 to 2.79 which has contributed a lot to their growth. Bangladesh and Vietnam have had a massive productivity boom to 5 and 6 tons respectively.

https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/cereal-yield?tab=chart&country=BGD~VNM~THA~TWN~ETH~OWID_ERE~KEN

To me it doesn't appear that export-led growth has failed. It literally hasn't even been tried yet in many poor countries in Africa since agricultural productivity has been neglected.

2. Would you agree that part of the reason why Asia sucked up manufacturing was because they were near Japan and Japan was basically the first foreign direct investor in Taiwan, SK, Thailand, and then later China when it opened up? Meanwhile, at the same time, large swarths of Africa were nationalizing industries and the would be big investor - South Africa - was an apartheid state focused on destabilizing its neighbors rather than invest factories in them.

As a bangladeshi citizen Noah being optimistic on the future of Bangladesh makes very optimistic as well. I have my own theory on the future of my country. Below I'm sharing a reddit post I wrote a few days ago.

Bangladesh economic prospects in 2041 (3 Possible Scenarios)

Scenario 1: Industrialisation stalls because of poor infrastructure investments. Unlikely since the recent government's actions and also because we're an easy country to build infrastructure for. We have huge population and a large network of waterways. Unlike Philippines which is a bunch of islands. Hence our infrastructure costs per capita is low and return on investment is also higher.

Per capita income stuck at 3.3k (modern Philippines)

Scenario 2: Unable to create globally competitive contract manufacturing because of weak electricity and gas supply. I think technology will solve some of this problem because of solar panels, batteries and industrial heat pumps. By the 2030s we should be privatising electricity generation and retail (with transmission in public hands). Gas pipelines will be largely irrelevant since both households and businesses will move to electric heating systems.

Per capita income stuck at 5.5k (modern Indonesia)

Scenario 3: We manage to become effective contract manufacturers but we can't innovate. Basically we can create Foxconn but not a Apple. Contract manufacturing is a low margins business, majority of the money is engineering design, marketing and after sales services. There is a reason Walton has their R&D labs in Korea and not in Bangladesh. This is because of weak legal institutions, political instability, and culture. A open society that enables innovation is an underrated thing. No one is entirely sure how something like this can be created.

Per capita income stuck at 7.7k (modern Thailand)

A falling fertility rate is also a big pain point. An aging society will place additional burdens on the next generation. Additionally there is less roam for innovation if the country is full of a bunch of old farts.