Malaysia: Truly Asia

A brief visit to a country that has mostly made it.

After I spoke at the Network State conference in Singapore this week, I took a three-day side trip to Malaysia. As I always say, there’s a very limited amount you can learn about a country by going there and wandering around the capital city for a couple of days, so I’m not going to pretend that this little vacation gave me deep insight into the country. But people do seem to like these little travelogue posts — here are the ones I did for the Netherlands, Taiwan, Ireland, and Singapore — so I figured I’d do one for Malaysia too.

Very few people outside Malaysia seem to care about the country, or even know much about it, and that’s not surprising. It’s not very big — just 35 million people or thereabouts. It’s at the lower end of the income scale for a developed country — about $43,000 in per capita GDP (PPP), similar to Turkey or Greece. It doesn’t have many cultural exports — you won’t see M-pop bands, or M-dramas, or Malaysian movies winning international awards. Malaysian food isn’t even very distinct; it’s a blend of dishes from nearby countries, maybe with a bit more spice and oil. When my Singaporean friends tell me they go to Malaysia “to eat”, what they primarily mean is that they go to eat various types of southern Chinese cuisine but with a lot more spice and oil than Singaporean restaurants typically serve.

I think this gets at a big reason Malaysia doesn’t occupy much mindshare, which is also a reason it’s an interesting country — it’s basically an international crossroads. Geographically, it’s located close to China, India, Indonesia, and Thailand, and because of its majority Muslim religion it has connections to the Arab world as well. There was sort of a small Malaysian Empire around 1400 to 1000 years ago, and an even smaller one around 500 years ago, but Malaysia has spent most of its history ruled by outside powers (most recently the British) who brought in outside cultures and people to mix in the area.

More than perhaps any other country, Malaysia is — as the famous tourism slogan says — truly Asia.

A little over half of the people in Malaysia are part of an ethnic group called “Malays” (hence the name of the country). If you think of a “race” as a bunch of people who all have similar appearances, then “Malay” isn’t really a race. It’s more like five races in a trenchcoat — Javanese, Thai, Bornean, Indian, Chinese, and some other smaller ones mixed in. You immediately notice this walking around Kuala Lumpur — other than hijabs for women and thin moustaches for men, there isn’t much to indicate that you’re looking at one singular “people”. Nor is “Malay” even really an ethnicity, if an “ethnicity” is a bunch of people who speak the same language; the “Malay” language is broken up into a bunch of different local dialects.

In the years since independence, the Malaysian government has worked hard to create unity from this jumble of diversity. Religion has been used as a force to unify the Malay people — in order to be classified as a Malay in Malaysia, you have to be Muslim, and the government tries to enforce a single nationwide form of the religion.

The Malaysian government has also tried to create uniformity through race. They created a new racial concept called “Bumiputera” (or “Bumi” for short), meaning “sons of the soil”, which includes the Malays and some minorities. If you ever doubted that race is a social construct, check out the Bumiputeras. Essentially, it’s a political coalition — the Bumiputeras stand in contrast to the Chinese, who make up almost a quarter of the country’s population.

The Malaysian Chinese are an economic elite, owning many of the country’s businesses, and the Bumiputeras were basically created as a coalition to make sure everyone else got a cut of the money and power. Racial discrimination is enshrined in Malaysian law, with part of the Malaysian constitution ensuring that Bumiputeras get government jobs and other benefits, and a long-running economic policy ensuring that Bumiputeras own a significant amount of the country’s stocks and get various other economic support. Malaysians — or at least, Malaysian Bumiputeras — generally prefer to think of these policies not as racial discrimination, but as “affirmative action”.1

So anyway, Malaysia is an incredibly diverse place that’s in the process of trying to force itself to think of itself as homogeneous. It’s an interesting case study for Americans who believe the now-fashionable right-wing dogma that diversity breeds conflict. On one hand, Malaysia has a history of conflict between Malays and ethnic Chinese — often including race riots — which is why Singapore separated from Malaysia in 1965. But as of today, Malaysia has a wildly diverse cobbled-together “majority” and a very substantial Chinese minority, and yet it’s one of the safest countries on the planet. By the most recent measurement, Malaysia has a murder rate of 0.74 per 100,000 — lower than Sweden or Denmark, and barely higher than China. The numbers are probably a little bit understated, but not by much.

I don’t want to over-interpret my impressions from just walking around, but you can sort of feel this safety on the street. No one seems nervous, everyone seems friendly and relaxed. There are some security guards, but they’re not armed, and there’s not much police presence at all. Nor do Malaysians seem to feel a need to sequester themselves in far-flung suburbs or compounds for physical safety — driving outside of the city center, you see endless forests of apartment towers, similar to what you see in Taiwan, Hong Kong, or Singapore.

Malaysia is a developed country, but Kuala Lumpur feels like it’s still developing. The city is an absolute jumble of different urban layouts, land uses, and architectural styles.

Massive arterial roads exist right alongside little decaying side streets and glittering, immaculate shopping areas. There are gas stations next to apartment towers, overgrown lots next to scenic tourist sites. Everyone jaywalks, even across major roads. Cars are everywhere, but there are a ton of people just standing around on the street.

It’s hot on the street. Malaysia is nearly smack dab on the equator, and it’s pretty much the same weather year-round — hot and muggy. As in Singapore, air conditioning is life here; without it, it’s hard to think straight, and as Lee Kuan Yew pointed out, you can only get work done at dawn or dusk. It’s not pleasant to think about the half of the Malaysian population who still have to go without it, trapped in sweltering dark rooms in front of buzzing dusty fans. In Malaysia, economic success means owning an air conditioner.

This is why you have to go to the Global South to really understand why economic development is so important. Heating a home through a cold winter doesn’t require advanced technology — farmsteads were burning wood and dung for heat since time immemorial. But dumping heat out of a building is a lot harder; you need an AC. And as the world gets hotter, large swathes of humanity are going to need AC to survive, not just to feel comfortable. Every pious upper-class German and sanctimonious Brit who dismisses the importance of air conditioning, or complains about the carbon emissions, should take a trip to Malaysia and try going without it for a few days.

Malaysia’s heat also made me a bit more pessimistic about the future of walkable urbanism. People walk down the street to shop in Malaysia, but they don’t like it; shop-lined streets tend to be more shabby and downmarket, while all the upscale retail is packed into glittering, air-conditioned malls.

Japan is discovering this now. Climate change has made Japanese summers almost unbearably hot — hotter than Malaysian summers, in fact. This is rapidly turning Japan’s famous, wonderful, walkable urbanism into a liability for months out of the year, and it may be one reason why so much of Japan’s new retail development is concentrated not in traditional zakkyo buildings, or shotengai (covered outdoor arcades), but in large indoor malls of the type that you see all over Southeast Asia.2

Southeast Asian malls are the future, and that future is boring. Shop-lined streets develop slowly and organically over time, with independent businesses trickling in and out, sometimes getting a good deal on rents. The selection of shops in a mall tends to be centrally managed, and the managers tend to pick big chain stores and famous brands rather than quirky indie businesses. Malls also squeeze tenants for every drop of rent they can, meaning that indie stores with smaller profit margins have trouble competing for space. More and more interesting retail is going to move online.

The nights in Kuala Lumpur are still hot and muggy, but at least the sun isn’t beating down. And that’s when the streets come alive. Tons of people just stand around on the street in the central districts, or stroll around with their dates, or drink in open-air bars, or shop at food stands. Rock bands set up and play on street corners, and people just gather in crowds and dance. Malaysia’s street scene isn’t quite as lively as you might find in, say, Latin America or South Europe, but seeing a bunch of women rocking out in hijabs makes it clear that “Muslim country” can mean a lot of different things.

Anyway, Kuala Lumpur feels like a city in progress. New malls and apartment buildings are going up everywhere, often in a chaotic, jumbled fashion. Money is obviously pouring in.

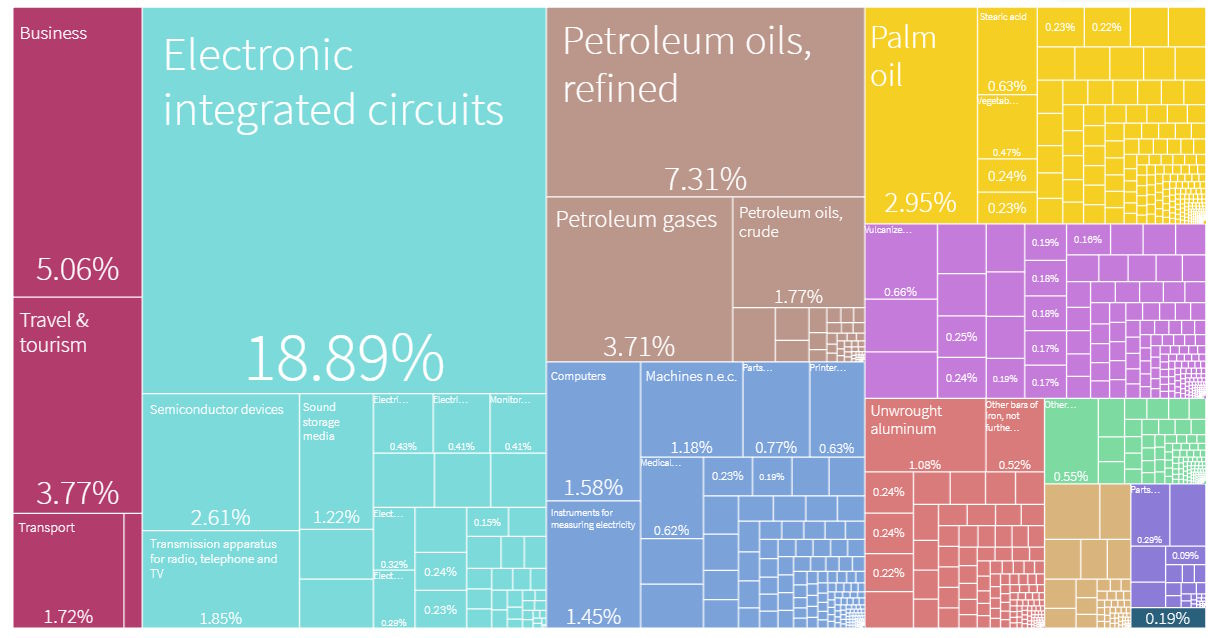

Where is it pouring in from? Malaysia is a very export-oriented economy — exports are more than two-thirds of GDP, compared to only about one-fifth in China or Japan. Malaysia has always had a thriving commodity export business — that’s why the British wanted it. It still sells a significant amount of oil, gas, palm oil, and the like. But in recent decades, the country has built up a world-class electronics industry. Electronics — especially semiconductors — now make up the biggest chunk of Malaysia’s exports:

Much of this industry was built by foreign companies that set up in Malaysia. But it’s the Malaysians themselves who have learned how to do the hard technical work. The country is now the international hub of crucial parts of the semiconductor supply chain, like packaging and testing. And it’s slowly climbing the value chain from low-end legacy chips to the high-tech, high-value new stuff.

In fact, tiny Malaysia exports almost twice the total amount of semiconductors that the United States of America does — $74 billion to $43 billion. In per capita terms, that’s almost 16 times as much chip exports per capita as the U.S. Not bad for a post-colonial Muslim country in an underdeveloped region, eh?

Malaysia is touted as an industrial policy failure in the book How Asia Works, because it never managed to build a domestic auto industry. But simply letting in foreign electronics companies and targeting crucial pieces of the semiconductor supply chain proved to be a huge industrial policy success. That’s the reason all those new buildings are going up in Kuala Lumpur, and that’s the reason more and more Malaysians can experience the blessing of air conditioning.

So there are actually a few reasons why people around the world should pay more attention to Malaysia. Their experiment in forging a majority identity group out of wildly disparate parts has a lot to teach the world about the social construction of race and nationhood. And Malaysia’s success in the electronics industry has made it the second developed country in Southeast Asia, after Singapore (not counting the petrostate of Brunei). It provides a model that larger nearby countries like Vietnam, Philippines, Indonesia, and Thailand might be able to follow.

This whole arrangement, and the Bumiputera concept itself, made me think of the “POC” concept in modern America. The idea of treating Nigerian Americans, Korean Americans, and Bangladeshi Americans as a single racial group was always a little far-fetched, but it makes sense when you understand that racial identities often start as attempts to forge durable political coalitions. In America’s case, that meant forming a nonwhite grouping to balance out the seemingly unified power and redistribute the disproportionate wealth of the White group. “POC” hasn’t really solidified as an identity, and I doubt it will, but if it did, it would probably look a bit like Malaysia’s Bumiputera.

Fortunately, some Japanese developers are fighting this shift by installing AC and other cooling devices outside buildings, and by building semi-outdoor quasi-mall spaces where indie businesses can still thrive.

“Their experiment in forging a majority identity group out of wildly disparate parts has a lot to teach the world about the social construction of race and nationhood.”

Noah, come on. They formed a group that was inclusive so long as it excluded *a quarter of the population*. They are united by their shared hatred of the Chinese, due to their success.

Do you think forging a shared American identity around hatred of say, Jews, would be a positive development? Certainly, there is appetite for that on both ends of the political spectrum. How unifying!

People can forge a shared identity when there is a hated market-dominant minority to plunder. Some teaching!

I thought Malays were racially austronesians? Like not East Asian like the Chinese minority but more like the Indonesian or Philippine majority race