The Poland/Malaysia model

A get-upper-middle-class-quick scheme

This is the second-to-last post in my long-running series about developing-country industrialization. The final one will be about India. Today’s, however, is about two of the most successful industrializers of the last three decades: Poland and Malaysia.

The generally acknowledged development champion of the modern world is South Korea. Joe Studwell, the author of How Asia Works, uses Korea as his paradigmatic success story, as does the economist Ha-Joon Chang (who grew up there). Chang and Studwell’s ideas have forced mainstream economists to take another look at industrial policy — in particular, at the idea that poor countries should promote manufactured exports in order to raise their productivity levels. Korea, which has fully made the transition from poverty to developed-country status over the last half century, has used this strategy to great effect. In general, in this series of posts, I’ve tried to look at developing countries through the lens of the Chang/Studwell model, which means I’ve been implicitly comparing them to South Korea all along.

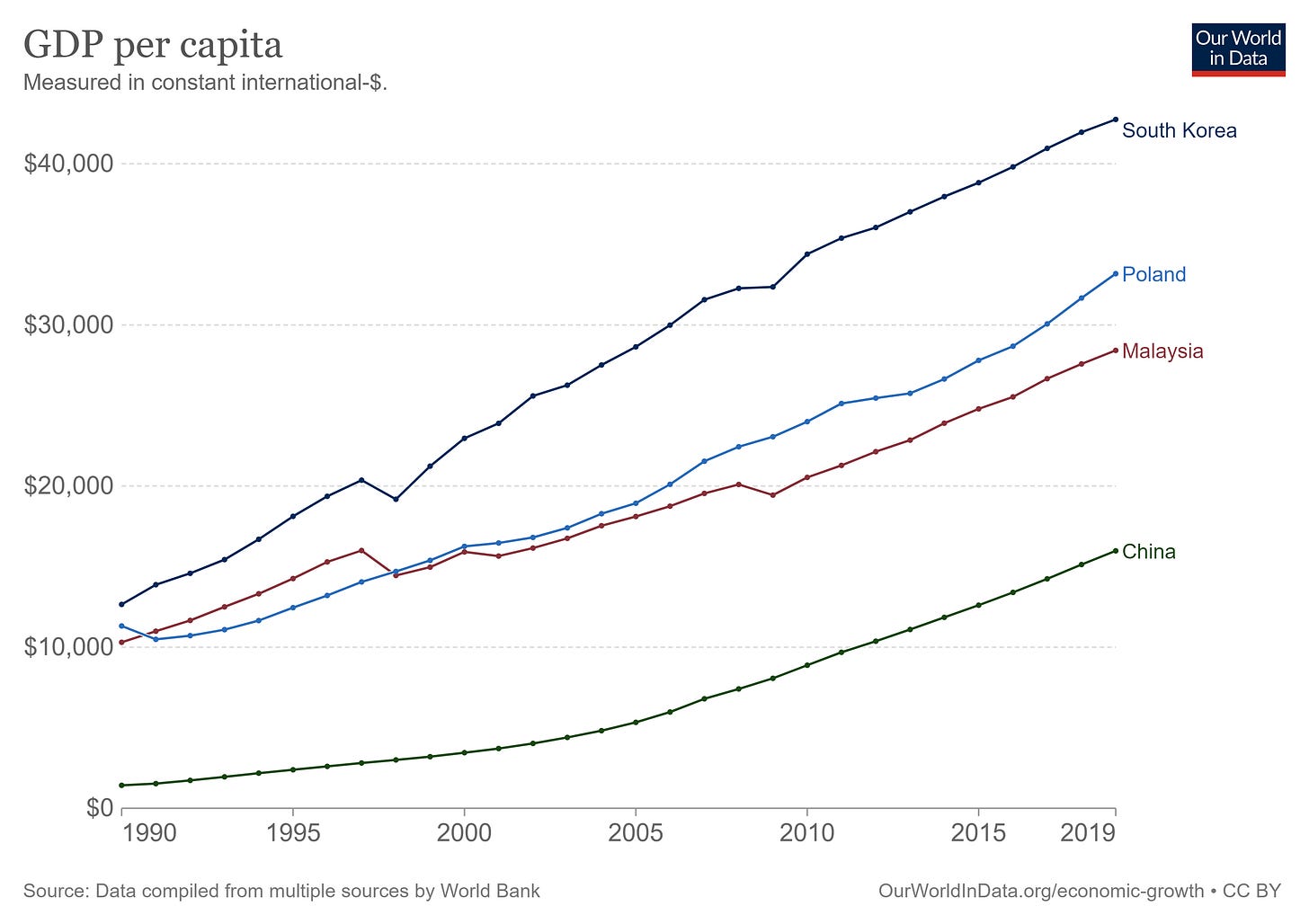

But anyway, South Korea is not the only big development success story that we’ve seen in recent decades. Two others that are almost as impressive are Poland and Malaysia, which are now on the cusp of developed-country status. Here’s a picture of how they stack up, with China thrown in as well:

China, of course, has had a much higher percentage growth rate, but that’s because it started off so much poorer. The richer you get, the harder it is to grow, so by reaching the ~$30,000 range, Poland and Malaysia have accomplished an impressive feat that China hasn’t yet. They’re not quite as impressive as South Korea, but then again, who is?

But the even more interesting thing about Poland and Malaysia — and the reason I’m bunching them together even though their geographies and industries and governments and cultures are very different — is how they developed. Unlike South Korea, they relied heavily on foreign direct investment. And this is important because FDI is both A) relatively easy compared to home-grown investment, and B) something that Chang says you’re supposed to avoid, at least in the early stages of development. If there really is an FDI-centric model that lets your country get rich, that’s incredibly good news for the rest of the developing world, because it’s probably a lot easier to copy Poland and Malaysia than to replicate the success of South Korea.

So that’s why these two countries are so important. Anyway, let’s take a look at what these countries’ economies and policies look like, before moving on to the central question of how others can follow in their footsteps.

Poland and Malaysia: an overview

The central message of the Chang/Studwell industrialization theory is exports. The idea is that competing in hyper-competitive world markets, rather than sticking to safe domestic markets, forces companies to raise their productivity, both by importing foreign ideas and (eventually) by innovating. And Poland and Malaysia are both very export-intensive economies — as much or more so than South Korea.

(Side note: This isn’t always a great way to compare countries, since smaller countries tend to be a lot more export-oriented than bigger ones. But since the populations of Malaysia (33.6 million), Poland (37.8 million) and South Korea (51.7 million) are all in the same ballpark, it’s probably OK to plot them all on the same graph. Also note that countries tend to become less export-oriented as their domestic economies grow, which is one reason why Korea has become more inward-focused in the last decade.)

Since in this story productivity is the real goal of exporting, it’s considered important that these be manufactured exports, rather than exports of natural resources — it’s a lot easier to improve productivity in manufacturing than in resource extraction. Manufacturing also tends to increase an economy’s “complexity”, which some economists think is important for growth. And manufacturing has substantial “multiplier effects”; every dollar or zloty or ringgit of money that it brings in tends to stimulate domestic economic activity as well, via suppliers and local services.

Anyway, Poland and Malaysia are both doing quite well on the manufacturing front. Poland’s exports are very diversified, but the electronics and automotive sectors make up the biggest pieces. Malaysia’s exports are dominated by electronics.

In fact, this is a pretty standard pattern; electronics and/or automotive goods will form the backbone of industrialized countries’ manufactured exports, because they A) are high-value-added, B) are relatively easy to transport long distances, and C) tend to involve long supply chains.

Malaysia actually tried to build an auto industry and failed — in fact, this is the subject of a whole chapter of How Asia Works. Long-time Malaysian leader Mahathir Mohamad tried very hard to turn the domestic automaker Proton into a world-beating brand like Korea’s Hyundai, but it was utterly unsuccessful. Studwell spends a lot of time talking about why this episode shows the superiority of South Korea’s policies over Malaysia’s.

But Studwell’s dismissal was a bit premature. Though it failed in autos, Malaysia succeeded wildly in electronics, becoming one of the world’s top exporters in this field. It exports more integrated circuits than the United States — $65B vs. $44B in 2020 — despite having a population roughly 1/10 the size and a GDP roughly 1/20 the size. It exports more semiconductor devices as well. In per capita terms, its computer exports are about twice as high as the U.S., and about the same as South Korea.

But unlike Korea, Malaysia did this without really building any well-known electronics brands. It’s easy to name internationally recognized Korean chipmakers — Samsung and SK Hynix. But it’s very hard to do this with Malaysia. If you google for top Malaysian semiconductor companies, they’ll all be foreign companies invested in Malaysia. The biggest domestic players in the industry, none of which are very big, are all outsourcing firms that do things like semiconductor testing and packaging.

In other words, Malaysia built up a world-class semiconductor industry by inviting foreign companies to invest there. The story of how it did this is fun, but ultimately pretty standard and unsurprising. For a good overview, I suggest this 2017 paper by Rajah Rasiah. For example:

Electronics manufacturing expanded sharply in Malaysia only after the introduction of export-oriented manufacturing in 1971, which was promoted through the second Malaysia Plan of 1971–5, and the opening of [Free Trade Zones and Licensed Manufacturing Warehouses] in 1972. The prime objective of these zones was to attract FDI to generate jobs, which the government managed through the development of export-processing zones to house giant firms from abroad engaged in light manufacturing activities. To facilitate the inflow of FDI, the government offered financial incentives (tax and tariff operations through tax holidays and investment tax credits for a period of five years) to firms locating at FTZs and LMWs, which were renewable for another five years.

This is very standard, textbook stuff. Make some special economic zones. Make sure they have enough transportation, electricity, water, etc. Make sure you have a bunch of workers who know how to read and are willing to work hard all day. Offer foreign companies a bunch of incentives — tax breaks, subsidized capital, etc. — to put their factories there, as long as they export the things they make. And as they say, if you build it, they will come.

One important thing to note about this strategy is that it very easily concentrates economic activity within a few special zones. This is important in order to take advantage of clustering effects. In Malaysia’s case, the most important zone was the state of Penang, especially the town of Bayan Lepas, which has become one of the region’s most important electronics hubs — not quite a Silicon Valley, but crucial to Malaysia’s national development.

Anyway, the Malaysian government launched a second round of export-oriented FDI promotion in 1986, which featured much more of the same. In the 90s the government realized that it ought to upgrade its manufacturing activities to higher-value stuff like semiconductor fabrication, and formed state-owned enterprises called Silterra and 1st Silicon to try to do this, but, like Proton in the auto industry, they largely failed and were sold off to foreign companies. Malaysia then began to suffer as some of the labor-intensive low-value-added work it specialized in migrated to cheaper countries like China.

At that point the government had another idea — pay foreign firms to do research in Malaysia, rather than just low-value assembly. This gave the semiconductor industry a huge boost; foreign companies started to do a bunch of higher-value-added stuff in Malaysia, though they kept their most cutting-edge and highest-tech stuff out of the country. Once the R&D was there, it created an incentive for fabrication and suppliers of all sorts to be in Malaysia too. Thus, low-level R&D — basically, figuring out ways to make older, non-cutting-edge chips more efficiently — was enough to retain Malaysia’s status as a major chipmaking cluster, but not enough to boost it to the cutting edge. That remains a task for the future.

Poland’s story is very different, but somehow ends up in a somewhat similar place. Most analyses of Poland’s development tend to focus on its transition away from communism and central planning after 1989, and on its accession to the European Union in 2004. Many scholars believe that joining the EU prompted a bunch of deep institutional changes that were extremely beneficial for Poland. For example, this is from a review of Marcin Piatkowski’s book Europe’s Growth Champion:

Culturally, Poland has benefited from a social consensus emphasizing the “return to Europe.” Communism was treated as a historic aberration and a foreign (Russian) imposition. Hence, a large majority of society wanted the country to join the European Union (EU)…Polish society was willing to make the necessary sacrifices to join the EU and thus achieve the symbolic status of a “normal” European country. These sacrifices included the adoption and implementation of Western institutions and practices (strengthening of the rule of law; implementation of modern banking, financial, and educational systems; reduction of corruption; etc.). The process turned out successful and contributed to a positive feedback loop leading to even faster growth.

This institutional improvement probably did a lot to encourage growth, but here I want to focus on export manufacturing. Poland, like Malaysia, attracted a lot of FDI, with the first big inflows coming in the late 90s. Here’s a graph showing Poland and Malaysia compared to the famously FDI-intensive economy of China; as you can see, they’re quite comparable.

How did Poland do this? Well, being close to Europe, having EU-compliant institutions, and having cheap labor certainly helped. But the big FDI boom started almost a decade before Poland joined the EU. What happened in the mid-90s?

At least part of the answer, unsurprisingly, is “special economic zones”. Starting in 1995, Poland created a bunch of SEZs with all of the usual tax incentives and infrastructure. Here is a good overview of the history and specific policy details, and here is a (translated) paper with some numbers. But there’s nothing really unusual here. As in Malaysia, note that increasing exports was explicitly a goal of the SEZs.

The Polish SEZs have been very successful in attracting foreign capital. But it’s not clear whether Poland’s zones were as crucial to its development into a manufacturing export powerhouse as Malaysia’s Penang electronics cluster. The timing of the first big FDI inflow into Poland lines up well with the creation of the SEZs, but that could just be a coincidence. Maybe European companies might have stampeded to invest in Poland after communism and EU accession, even without government encouragement. (Research papers do tend to find a positive effect of SEZs on local investment and employment, but it’s hard to know if that effect just represents a reallocation from other regions). Whereas Malaysia’s foreign investors include countries from all over the world — Asia, Europe, and the U.S. — Poland’s big investors are mostly, though not all, in Europe itself:

This suggests that physical proximity might have exerted a more important pull there. Most importantly, Poland was right next door to Germany, its biggest foreign investor. (There are times when being right next door to Germany has not been an advantage for Poland, but in this case it was a stroke of luck.) On the other hand, the U.S. and Japan do invest a significant amount, and South Korea’s investment in Poland is ramping up. So Poland’s policies to attract FDI might have been decisive after all.

Anyway, Poland has a ton of manufacturing exports, but like Malaysia it has no real top manufacturing brands; it relies mainly on foreign companies coming in and building stuff there. You can’t really name a Polish electronics company, and the one big automotive brand is the electric bus maker Solaris. And like Malaysia, Poland is having some difficulty upgrading to the highest levels of productivity, because it hasn’t yet moved into higher-value-added activities. This McKinsey report from 2015 lays it out:

Since its accession to the European Union in 2004, Poland closed 27 percent of the productivity gap with the EU-15. Despite the progress, Poland’s comparative labor productivity in 2012 remained low in a few key sectors, at two-thirds the EU-15 average…The shortfall is [partly] a result of the low position in the value chain…along with the relatively low level of capitalization in the economy.

Despite all the foreign factories, manufacturing is one of the main sectors where Polish productivity lags:

Like Malaysia, Poland still has one rung of the development ladder left to scale.

Have Poland and Malaysia found a get-rich-quick scheme?

At this point, let’s take a moment to talk about why Ha-Joon Chang and some other industrial policy fans think that FDI is not the basis of a sound development strategy. Chang has gone to great lengths to show that today’s rich countries — the U.S., Japan, and so on — restricted or even banned FDI during their early stages of development. But that doesn’t tell us why it’s bad, or even if it’s bad; the rich countries could have succeeded in spite of this policy. Part of Chang’s distaste for FDI comes from the fact that a lot of it is actually just foreign companies acquiring local ones, rather than building new factories; this could result in the foreign companies stunting the growth of the local ones, whereas if they had remained independent they could have risen to become competitors. Also, some FDI goes into real estate, which often just pumps up property values unhelpfully and may set economies up for bubbles and crashes.

But another reason the industrialists are suspicious of FDI is that even “greenfield” FDI — i.e., when a foreign company comes in and builds its own factory in your country — might crowd out domestic companies. If all the good engineers and managers go to work for foreign companies, it could starve local startups of the resources they need to grow. And since foreign companies are likely to reserve the highest-value-added parts of the supply chain (design, high-tech, branding, marketing, etc.) for their home countries, having a manufacturing sector dominated by these multinationals could prevent a company from developing its own globally competitive brands and technologies — like an apprentice whose master will never let him learn his most secret tricks of the trade.

Poland and Malaysia may now be running into this problem. McKinsey cites Poland’s need to develop or acquire strong brands in order to catch up with West Europe. The failure of Malaysia’s attempt to build domestic champions is worrying.

And yet I see two responses to this. The first is: Do we really care? Poland and Malaysia may not be as rich as Germany or Korea, but they’ve definitely escaped poverty. Countries like Bangladesh or Vietnam or Ghana or even Mexico would kill to have a per capita GDP of $30,000. That’s about the GDP of the U.S. in the early 1980s. Is it really fair to call that level of development a “middle income trap”? If you’re a poor country, and you have a reliable, dependable way of getting as rich as the U.S. was in the early 1980s, dammit, you take it. You don’t worry about whether that strategy will eventually make it harder to get as rich as the U.S. of 2023.

Because developing the South Korean way, by building a bunch of world-beating high-tech manufacturing companies from scratch, is incredibly hard. An FDI-centric strategy, on the other hand, is simple and straightforward, almost cookie-cutter — you give all your people a high school education, you build some roads and electric power lines and sewage lines, you designate some Special Economic Zones, and you give foreign companies big tax incentives and investment incentives and regulatory incentives to come in and hire your plentiful low-wage workers to make electronics and automotive goods and other complex products for export. Voila! No need to build the next Samsung or the next Hyundai; the existing Samsung and Hyundai will do nicely.

This is a bit similar in spirit to the way Tennessee, Kentucky, and Alabama lured U.S. automakers away from high-wage unionized northern states with the promise of cheaper non-union labor. You don’t see Tennessee or those other states becoming home to the new Detroit; all the big car brands are still headquartered elsewhere. Eventually this strategy ran out of gas, but it worked for a while.

And for poor countries, “a while” may be long enough. There are plenty of countries around the world that could potentially use the Poland/Malaysia model as an easy rote method for getting into the upper middle income tier instead of waiting around to figure out how to craft their own bespoke path to being the next South Korea. I’m thinking about Bangladesh, Vietnam, India, Indonesia, Ukraine, Tanzania, or even some poor resource exporters like Ghana. Imagine going from the bottom group to the top group in this chart. Would you really worry about whether that would put you in the “middle-income trap”?

Then there’s the possibility that the fears about FDI’s long-term impact are simply overblown. For example, take brands. Poland is starting to build a few good manufacturing brands of its own, including Solaris, the household appliance maker Amica, and the bathroom appliance maker Cersanit. And outside of manufacturing, Poland is starting to build some brands in other sectors like retail, software, and entertainment. You might not recognize the names of any Polish carmakers, but chances are you know who this is:

I just wrote a post about a Polish-Japanese anime collaboration the other day.

And as for technology, eventually, investments in good universities and strong intellectual property systems will bear fruit. High-tech startups might require a bit of government support at some point to poach talented locals away from the multinationals, but that doesn’t sound like an impossible task. And it’s a lot easier to be trying to solve this problem when you’re at $30,000 of per capita GDP than when you’re at $8,000.

So if Poland and Malaysia haven’t found the secret to getting rich quick, perhaps they’ve found the secret to getting upper-middle-class quick. That wouldn’t be a full general solution to the problem of industrialization, but it would represent an amazing advance over what we know now. If I were a poor country, this is what I’d be looking at.

One of the weirdest things reading this in Poland is how pessimistic everyone here is – about inflation, recession, the war, the government – and how much of a success story it's seen as elsewhere. There are a lot of factors for this – cultural, economic, etc. – but it really is quite the dissonance.

One thing I always tell people though is that while Poles SAY they're pessimistic, their behaviour suggests otherwise, people are investing in a way that implies they think life will be better and richer in 5, 10, 25 years. I will say financial behaviour has changed a lot since the war in Ukraine started though – at lot more thinking about cushions, worst-case scenarios and rainy-day savings instead of trying to maximise returns.

Also, in the context of the EU, I feel like Poland has been helped a lot by keeping its own currency instead of adopting the Euro. Everyone here is obviously concerned by inflation, but a low złoty helps exports which really are the key to keeping the economy going. I'd be much more worried about the economy without that.

"There are times when being right next door to Germany has not been an advantage for Poland..."

Oh dear.