Why Japanese cities are such nice places to live

The secret sauce of dense, mixed-use urbanism.

Every once in a while, American social media rediscovers tiny Japanese apartments. The latest instance of this was a video of a Japanese studio apartment in Tokyo that’s 250 square feet for $300 a month:

Now, that’s an incredibly good price compared to top American cities. $300 for 250 square feet is just $1.2 per square foot! A study last year found that rents in New York City are astronomically higher than that — $6.17 per square foot in Manhattan, $4.39 per square foot in Brooklyn, and $3.82 per square foot in Queens. You have to go all the way out to Witchita, Kansas — the cheapest city in the survey — to get down to Tokyo-like prices.

One reason for this, of course, is that Japanese cities like Tokyo build a ton of housing. But another reason is lower demand — Japanese people are, on average, much poorer than Americans, with less than half the median disposable personal income. This means they can’t afford to pay as much for apartments, so prices are lower.

But those prices are measured per unit of floor area. The fact is, even if you pay very low rent for a 250 square foot apartment, you’re still living in a very small apartment. And that’s not even the smallest — there are Japanese apartments as small as 108 square feet!

In fact, this is far from the norm in Japan. Tiny apartments used to be common in Tokyo, but the city’s massive and sustained building spree managed to double floor area per person between 1968 and 2013. The city now has living space comparable to Paris and London, and only slightly smaller than New York City:

And other Japanese cities have even more space.

But anyway, some of those tiny apartments do still exist, so let’s talk about them. In fact, when I was 25, I lived in a Japanese apartment slightly smaller than the one in the video for about half a year. It was cramped, yes, but it was actually a really nice living experience. And understanding why it was a nice living experience is helpful for understanding why American cities are so unsatisfying.

A lot of Americans will react with shock and horror to the idea of living in such a small space. To people raised in the land of giant suburban houses, a tiny apartment in the big city might sound like dystopia — the proverbial “living in the pod”. That visceral horror contributes to fears — not just among conservatives, but also some leftists and liberals — that YIMBY policies seek to force Americans to live packed together like sardines in tiny units like the one in the video above.

Those fears are irrational. YIMBYs don’t want to force anyone to live in tiny apartments; they simply want to allow apartments like this to be constructed, if there are people who do want to live in them. And I was one of those people.

Why was it so nice to live in a tiny apartment? Part of it, certainly, was that I was 25 and footloose, living in a foreign city and partying a lot. Part of it is that Japan, culturally speaking, is just a really friendly place (at least, if you know how to speak the language). But much of it had to do with how Japanese cities are built. Japan has really mastered the art of dense, mixed-use urbanism. This means that even if you live in a tiny apartment, the city around you is so nice that your live can feel very free and luxurious.

Mixed-use zoning with high commercial density

If you haven’t read this famous blog post on Japanese zoning, you should go read it. In a nutshell, American zoning tells you what you are allowed to build in an area — single-family homes, office buildings, etc. — while Japanese zoning specifies what you’re not allowed to build. This means that almost every zone is mixed-use — since almost no zones outlaw every possible type of shop, almost every zone has some stores in it. In other words, in America, relatively few areas can have stores, because the zoning laws have to specifically tell you “It’s OK to build a store here”. In Japan, if the zoning code doesn’t expressly forbid stores, you can go ahead and build them.

And most zones don’t expressly forbid stores. Here is an infographic of the 12 basic types of Japanese zones:

Because almost every area has stores and restaurants, even in the suburbs, you’re never far from a store or restaurant. This makes it a lot easier to live in a tiny apartment, because you don’t have to keep nearly as many things in your house.

In Japan, if I wanted a bottle of water, I could simply take the elevator down to the first floor, walk ten seconds to a drink machine or two minutes to a convenience store, and buy one. In most of the places I’ve lived in America — Ann Arbor, Long Island, College Station, and so on — I would have to drive from my house to a store to a store. That would take 30 minutes, just for a water bottle!

So if I wanted to drink water bottles sometimes, I would have to store some in my house. That takes up space. And the same goes for food, kitchen supplies, cleaning supplies, and so on. In Japan I wouldn’t have to hoard these things, because I could go get them very easily whenever I needed them.

Having restaurants nearby is also incredibly freeing. Going out to eat doesn’t have to be a cross-town excursion — any time you feel like it, you can just pop outside and duck into your local noodle shop or burger joint.

Having stores and restaurants within a couple minutes’ walking distance of your house does something else — it creates public space near your house.

In an American neighborhood zoned for residential use only, you have to leave your house and travel to a destination — a shopping street, a faraway restaurant, a park, a mall, etc. — just to see people you don’t know. Your house exists in the middle of a vast ocean of enclosed private spaces — houses and lawns, accessible only to the people who live there. Maybe you can walk down the street and say hi to people who are out on the lawn or walking their dogs, but that’s really your only contact with people outside your own household in your own neighborhood.

In Japan, by contrast, you see strangers in your neighborhood all the time — in the convenience store, in the noodle shop, or walking down the street from their own houses to those shops and restaurants. Even if you don’t like to meet strangers or say hi to your neighbors, it’s nice to see strangers and to see your neighbors. It creates a feeling of communality — of shared civilization and community — even if no words are spoken.

This is why in Japan, even if you live in a tiny apartment, it doesn’t feel like you live in a tiny, lonely space — you’re out and about so much that it feels like you live in a great big open space with lots of other people. American suburbia can feel confining and cramped because no matter how big your house is, there’s nothing and nobody outside those walls; in urban Japan, even with a tiny apartment, you occupy a great big neighborhood. That is very freeing.

Of course, all of this requires something besides mixed-use zoning — it requires high commercial density.

We tend to think of “density” as residential density — the number of people who live in a given area. But as the blog Urban kchoze argues, commercial density — the number of shops in an area — is very important for walkability.

You can have a neighborhood with a ton of houses but only a few shops. The “tower in the park” superblocks that have become popular in China in recent decades, and which used to be common in the old Eastern Bloc, are examples of this. These areas pack lots of people in, but because they don’t have many places to eat out and shop, they don’t create the open, friendly neighborhood effect of Japanese cities. There’s a shared lawn, but there’s not much to do in that lawn, and not many people to see.

Japanese cities, in contrast, have a ton of little stores and restaurants. One reason for this is that as you can see in the chart above, Japanese zoning explicitly limits the size of stores in residential areas; the more residential an area, the smaller the stores have to be. That’s very different from America, where the suburbs tend to be served by big-box stores.

In fact, Japan also has a national law protecting small stores — the Large-Scale Retail Store Law, which makes it hard to build a big-box store. This law was relaxed somewhat in the 90s, but it’s still important. It has some negative effects — small stores are inefficient, which raises consumer prices for Japanese households. It also probably has some beneficial effects on Japan’s political economy — it protects a thriving small-business-owning middle class, which in turn demands walkable neighborhoods and good transit systems in order to have more foot traffic for their stores.

But most importantly, it creates a variety of stores in a neighborhood. If every convenience store and noodle shop has to be small, you have to have a lot of them in order to serve local demand. And this creates local variety, which is fun and enjoyable. Walk five minutes, and there are five different restaurants you can try in your neighborhood; walk fifteen minutes, and there are fifty. That variety also allows for the creation of local “crowds” — in addition to a bunch of random customers who just walk by, you tend to see a smallish group of people who repeatedly frequents each of the places, which fosters community.

Public safety, low noise, public spaces, and trains

In addition to the basic ingredients of mixed-use zoning and high commercial density, there are a number of things Japan does to make its urban neighborhoods especially livable.

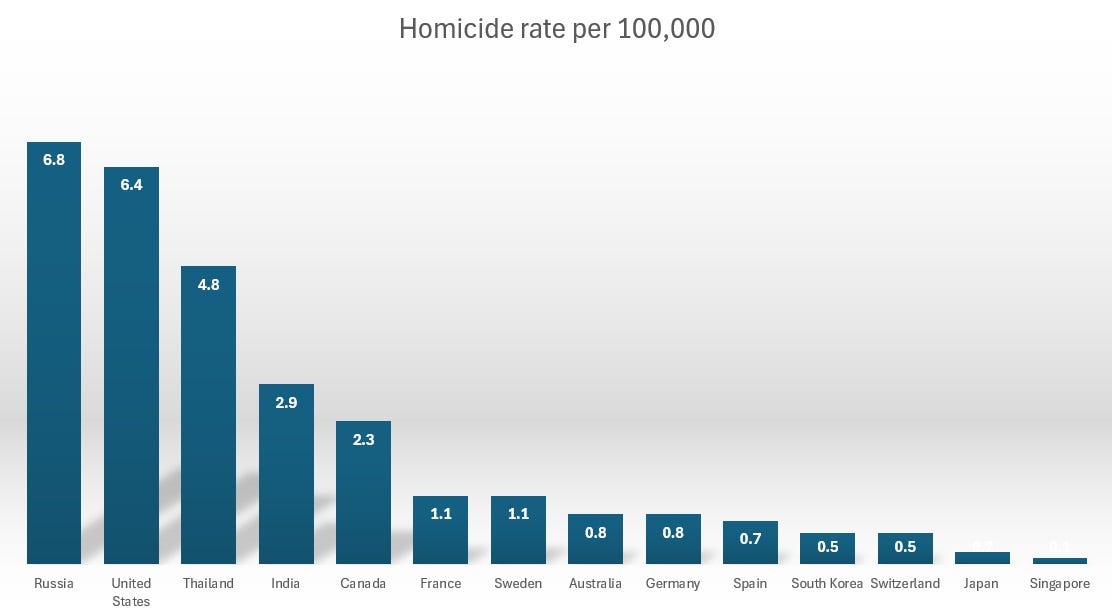

The first of these, of course, is public safety. Japan has one of the lowest rates of violent crime in the world. Its homicide rate, at 0.2 per 100,000, is one of the lowest in the world, even lower than European countries.

Good public safety makes people feel safer leaving their homes — especially women, and especially at night. This makes neighborhoods more vibrant and increases the feeling of community. And when it’s safe to go outside, living in a small apartment doesn’t feel nearly as confining; no one feels like they have to hide inside their house from muggers, rapists, etc.

But a city doesn’t have to be anywhere near as safe as Japan in order to reap major benefits from public safety. New York City is America’s safest big city, and it has the country’s most walkable, dense, vibrant neighborhoods. In fact, there’s a virtuous cycle between public safety and dense walkability — the more people are out walking around, the more “eyes on the street” there are to deter crime, which in turn makes more people feel safe walking around.

A second thing that makes Japanese cities incredibly livable is low noise. This isn’t just a function of culture; it’s the result of deliberate government policy.

In New York City, even in lower-density areas like Brooklyn, it’s common to hear the loud clanking of delivery trucks through your windows and walls early in the morning. In Japan, there are regulations about how noisy trucks and other vehicles are allowed to be. One way trucks minimize noise is to use hand carts instead of machinery to unload trucks; this increases costs but lets people get more sleep. There are also a ton of costly but effective technologies for engines, tires, etc. that companies use in order to satisfy the noise ordinances.

Newer Japanese buildings, unlike most buildings in NYC or other American cities, are designed to be soundproof. There are a vast array of technologies used to block sound from getting into people’s apartments — concrete walls, acoustic tiles, soundproofing wall and floor layers, double glazing of windows, and so on. All of this adds cost, of course, but Japanese construction costs are lower than U.S. costs for a variety of other reasons, so the overall price is still low.

Extremely low noise makes living in a tiny apartment in Tokyo feel a lot cozier and more peaceful than living in a much bigger apartment in Brooklyn. One reason Americans fear living in big cities is the constant clamor; in a modern Japanese apartment, you’re in a quiet cocoon.

Japan also tends to have a lot of very nice public spaces where people can walk around. These include urban parks, which tend to be very beautiful.

Many large streets also have very wide sidewalks that are protected from road traffic by trees, railings, and various structures. There are large open plazas in front of and inside of train stations. Many commercial developments, like Roppongi Hills or Midtown, have large plazas that act as public gathering spaces. And Japanese cities are rife with public commercial spaces in alleys, train station basements, covered shopping arcades, and even highway underpasses. Any residential neighborhood in Tokyo is likely to have some of these spaces nearby.

And of course there are the trains. Japan has arguably the best train system in the world. In large cities like Tokyo, the system is so dense that it’s rarely more than a 10-minute walk to the nearest train station; taking a train is usually faster than taking an Uber or taxi, and much much cheaper. A good train system means you’re not trapped in your little neighborhood; with only a little travel time, you can go to a whole new area and walk around. Of course, public safety makes the trains a pleasant and safe experience, and the train cars and stations themselves provide public spaces where you can see people, meet people, or even hang out.

All this public space does one thing — it makes the world outside your apartment feel big and accessible.

Living inside versus living outside

In his famous book Bowling Alone, the sociologist Robert Putnam documented how Americans have begun to “hunker” inside their houses, avoiding contact with the outside world. He attributed part of this to America’s increasing racial diversity, but quantitatively, this was only a very small part of the effect. My guess is that America’s built environment is a far bigger factor.

In America, you mostly live your life inside. Usually this means inside your home, your car, or your office. Occasionally it means inside a shopping mall or big-box store or a large restaurant that you drive to. But it means that you’re almost always confined within a space, which often contains only you, and usually contains only a set of familiar faces.

In Japan, in contrast, you mostly live your life outside. You spend a lot of your time walking around, seeing — or, if you’re not shy, meeting — strangers, discovering new places to eat and shop, enjoying the pleasant public spaces that a competent government and an innovative, well-regulated private sector have provided for you. You might return home to a tiny apartment, but unless you’re a hikikomori, you don’t stay there; your real life is lived outside. And when you do spend time inside your apartment or house, it’s quiet and cozy, even if you’re smack dab in the middle of the biggest city on the planet.

That’s what makes living in a tiny apartment in Japan tolerable, and — if you’re young — even fun. You don’t really live in the pod. You live in all of Japan.

I don’t think American cities are going to be able to replicate this level of urban walkability and pleasantness anytime soon. But they don’t have to. New York City, the closest thing America has to Tokyo, manages to achieve something almost as good. Its public safety is decent, its trains are serviceable, and many neighborhoods have bodegas and little neighborhood restaurants.

And millions of Americans absolutely love living in New York City! The rent is astronomically high in NYC not just because that’s where a lot of jobs are, but because if you want to live in a safe-ish dense walkable mixed-use city in America, that’s where you go. Americans elsewhere in the country who tremble in fear of “Manhattan-ization” every time an apartment building goes up in their neighborhood should realize that Manhattan is among the most desirable, sought-after living spaces in the whole country.

What America really could use — and what it’s within our power to create — is a few more Manhattans. With a little hard work, dedication and vision, quasi-dense cities like San Francisco, Chicago, and Seattle could replicate much of NYC’s train-centric mixed-use density. And even Houston and Atlanta and Dallas could build more dense, mixed-use neighborhoods if they wanted to. What they really need is the vision, and an understanding of why living in that type of neighborhood is so great.

The point about the shared lawn without much to do in that lawn, vs having tons of restaurants, cafes, bars, and stores in a neighborhood being incredibly freeing, is something I think a lot of urbanism activists in the US miss. There's a really strong anti-business segment of the US urbanism crowd that is vehemently opposed to shared spaces that people pay to use. I think that daily life in Tokyo really shows how business and good urbanism are absolutely not enemies.

In addition, something almost completely missing from the urbanism discussion in the West, is integrating industrial uses in dense urban environments. I work at a small industrial company, and it's so nice to be able to walk not only to my office, but also to my company's labs and workshops in the same neighborhood. Not every industrial building is an oil refinery or a rocket static firing range. Even though a sizable lab or workshop, or small factory or warehouse does present a longer than optimal blank wall to the street, they can fit well enough, and people working jobs that aren't office or retail should be able to live and work in nice neighborhoods.

Though on the topic of safety, I think improving the safety of US cities is very important. Even though NYC is fairly safe by US standards, it could be an order of magnitude better and still be short of world leaders. I really enjoyed your article a while back about Professionalizing the Police, and would be interested in hearing a more complete argument in why and how to improve safety in US cities. It feels like the safety debate in the US was stuck between the "law and order" types with mostly bad ideas about how to improve law and order, and "defund the police (literally)" types whose only response to legitimate safety concerns is gaslighting.

As a European who has lived all over the US for the past 14 years, this is what frustrates me: there’s clear market demand for mixed use development, since the cities and neighborhoods where it exists are always the most expensive to buy or rent a home.

I’m not just talking about New York and San Francisco, but the cute little historic main street of any American town you choose, where mixed use is grandfathered in. Why does modern planning prohibit the sensible kind of living that our ancestors figured out a thousand years ago?