Network State, or a Network of States?

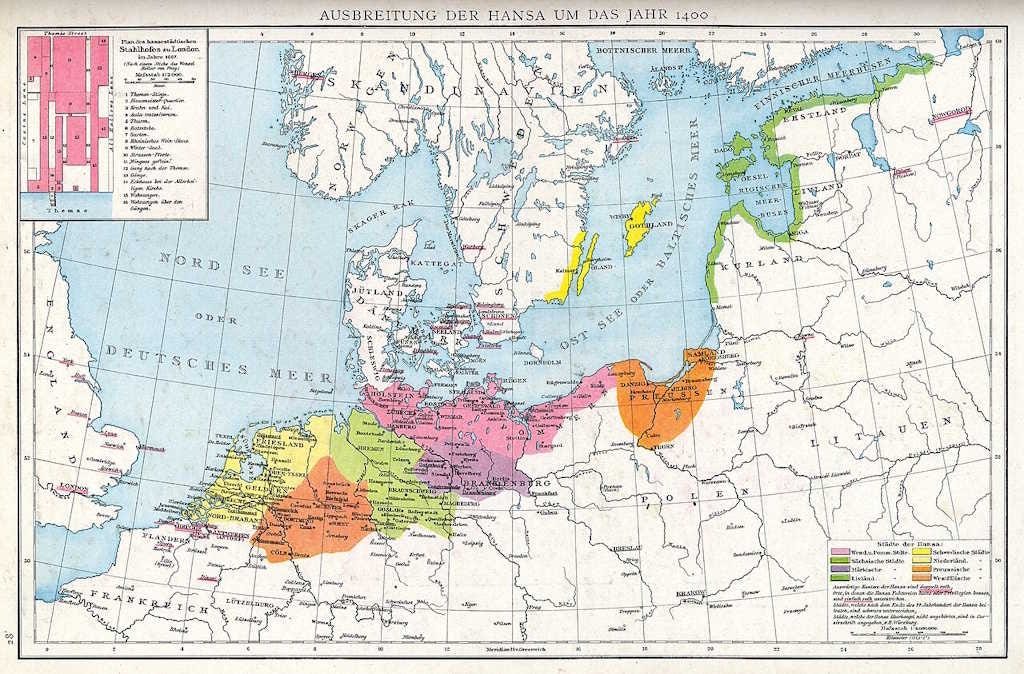

An idea for a new global Hanseatic League.

I’m writing this post on a plane, as I fly to Singapore for the Network State Conference on October 3rd. This conference is organized by my old friend Balaji Srinivasan, who wrote the book The Network State: How to Start a New Country. I will be giving a talk at the conference, about an idea for operationalizing and improving upon Balaji’s core concept. Balaji’s book was fairly idealistic and speculative, but I think I’ve figured out a way that a stable, functional network state could feasibly be created. This post is a preview of what I’ll say in the talk.

But before we get to that, I should mention that after Singapore, I’m going to be in Malaysia on the 5th, 6th, and 7th. If you’re in Malaysia, and you’d like to meet up, shoot me an email!

Anyway, first let’s talk about network states, and why the original idea needs some work. And then we’ll get to my big idea that I think has the potential to solve all of the issues.

Two fundamental problems with network states

The internet has de-localized many of humanity’s social interactions. In the past, almost all of the people you would know would be in your close geographical vicinity. Perhaps you might feel connection with some broader international concept (“Christendom”), or maybe you might maintain some networks of long-distance relationships (the early modern “Republic of Letters”), but almost everything you did and everyone you know would be governed by physical proximity.

After millions of years, the internet has abruptly upended this basic fact of human life. Many of our communities are now de-localized, consisting of like-minded individuals strung out across the globe. Your online social group could be an anime fandom, or Asians living in the Anglosphere, or a bunch of wisecracking tech people on Twitter. A couple of years ago I wrote a post contrasting these “vertical communities” with traditional “horizonal” communities, I mused about how the two might conflict:

Balaji’s book goes much farther than that post — it envisions online communities turning into something resembling a nation-state. Groups of like-minded people strung out over a vast distance, he argued, could band together to provide services like education, insurance, health care, private dispute resolution, and so on. They could function as business networks, providing preferential financing and business deals, perhaps using blockchains to obviate the need for local courts and banks.

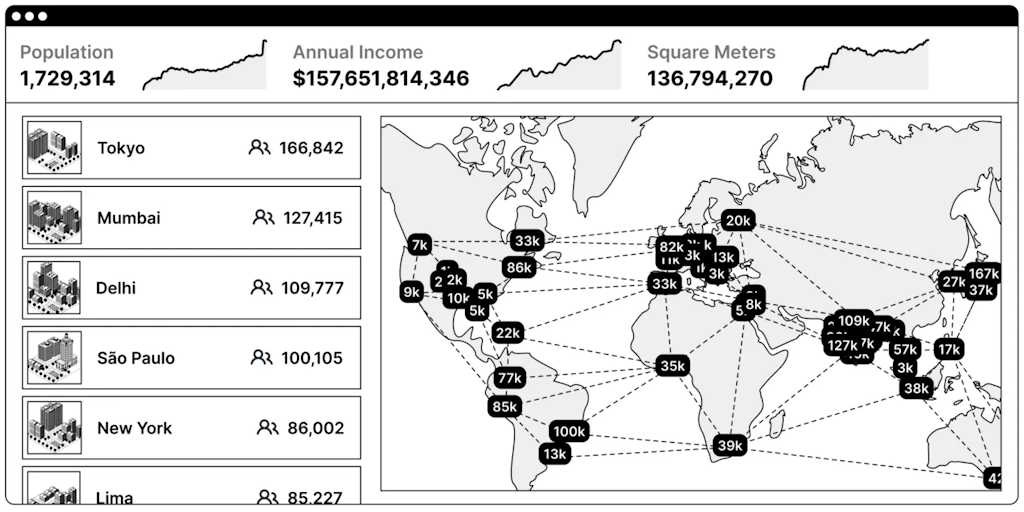

Balaji envisions network states buying up property in various locations — housing, conference centers, ranches, whatever — and using these as physical nodes where the members of a network state can gather. Eventually, he speculates that network states could conduct independent foreign policy, negotiating with traditional nation-states using the leverage of the global network to extract concessions of limited sovereignty — special tax treatment, trade agreements, and so on. Here’s a picture of what a global network state might look like:

This is a very interesting and novel idea. It has an undeniable appeal — who wouldn’t want to form a country composed purely of people you resonate with, rather than whoever just happens to live near you? What if “finding your people” via the internet didn’t just mean finding people to talk to, or work with, or date, but people to build your whole society with?

And yet we can immediately see at least two huge problems with Balaji’s idea.

First and foremost is the problem of public goods. These are things that nation-states traditionally provide, because private actors either can’t or won’t, at least in sufficient amounts — things like national defense, courts and laws, police and public safety, firefighting, infrastructure, scientific research, public parks, and so on.

The internet has made it possible to provide some public goods online — for example, some kinds of scientific research, or property rights, or anything that relies mainly on information and communication. But plenty of public goods still exist in physical space. And these are things that network states will struggle to provide.

For example, take physical infrastructure. Even if you’re a member of a network state, you need roads to drive on, airports to fly from, trains to ride, sewer systems, and so on.1 Who is going to pay for those? If members of a network state don’t pay their share of taxes to support the roads they drive on or the sewer systems they flush their toilets into, they’ll be free-riding. That’s going to cause anger in the short term, and breakdown of the road system in the long term.

Or take national defense. Members of a network state might negotiate lower tax rates for themselves, figuring if a neighboring country invades they’ll just hop to another country and avoid the fighting. But if network-state people didn’t pay enough taxes to maintain an army, the places they live in might be prone to getting overrun and conquered. Nobody is going to want them for a neighbor.

And a lot of people either can’t just pick up and move, or don’t want to; since time immemorial, people have fought for their land. As Tablet magazine put it in their review of The Network State:

What exactly drove hundreds of thousands of Ukrainian civilians to take up arms and risk being blown to bits in Russian artillery barrages rather than submit to Russian rule? Surely it wasn’t disagreement with Putin on property-tax regimes. No, something else is at work.

The kind of people who will fight and die for their land will be very mad at network-state types who enjoyed the fruits of peace when times were good but who abandoned their neighbors to their fate when things got rough.2

This gets at the second big problem with network states: they naturally conflict with traditional nation-states.

Many times throughout history, a group of people has carved out “privilege” for themselves, in the original sense of the word — a system of private laws that only applies to them and not to their neighbors. This invariably makes people mad, because fairness is a key human value. Whether it’s aristocrats who are allowed to carry special weaponry on the streets, or a certain religion you’re not allowed to blaspheme against, people who get visibly better treatment always spur resentment.

For network state members to negotiate “sovereignty” for themselves in the countries they live in means for them to have privileges that their neighbors don’t have, and that’s going to cause friction — to put it mildly. Just look at the backlash in Europe and the Anglosphere against the creeping recognition of sharia law that applies only to Muslim residents.

People who are rooted to a horizontal community — to a specific nation-state and a specific city — will also naturally resent neighbors who don’t put in their fair share and who seem ready to skip town at a moment’s notice. Network state “citizens” will, by definition, be rootless cosmopolitans, with all of the negative baggage that designation has traditionally created.

Network states work in theory, but they have little to offer to traditional states; the original concept is effectively parasitic on existing forms of human organization. Traditional states still have a major advantage in terms of organized violence; if network states can’t offer some kind of benefits to traditional states, they will eventually find themselves violently ejected.

That doesn’t mean the idea should be abandoned, though. I just think it needs some additional elements. So after thinking about the problem, here is what I came up with (and what my talk at the Network State Conference will be about).