Let's save the human species!

There's probably a solution out there to fertility decline. Let's find it!

Take a look at the marvel that is modern China. The endless gleaming lines of bullet trains. The air taxis and the drone delivery services and the driverless cars. The bubble tea franchises and the cavernous malls and the fast fashion and the pay-with-your-face apps and the robot waiters and the automated factories. The Shanghai clubs and the side streets of Chongqing and the manicured parks of Shenzhen.

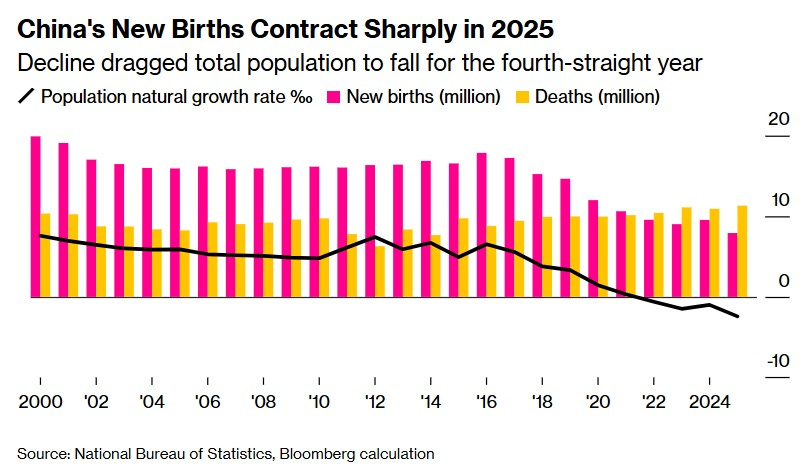

You are looking at the peak. China will continue to be a spectacular, world-leading civilization for a couple more decades, but sometime around the century’s halfway point, demographic decline will begin to sap its vitality. Sometime around the mid-2010s, China’s birth rate fell off a cliff, and has not stopped falling since:

It’s difficult to state just how stark and catastrophic of a collapse this is. The number of births in China fell by 17% in just the last year. In fact, as economist Jesús Fernández-Villaverde recently pointed out, China had fewer births in 2025 than in 1776, when its population was less than a fifth of what it is now.

China’s total fertility rate now stands at around 0.93, less than half the replacement level. At that rate, every four grandparents will have fewer than one grandchild. Fernández-Villaverde explains what this means for the future of China’s population:

[I]f China could somehow sustain 7.92 million births per year from now on, its population would eventually stabilize at roughly 625 million, far below today’s 1.405 billion. In reality, as smaller cohorts reach childbearing age, births will fall well below 7.92 million. Hence, 625 million is a very generous upper bound[.]

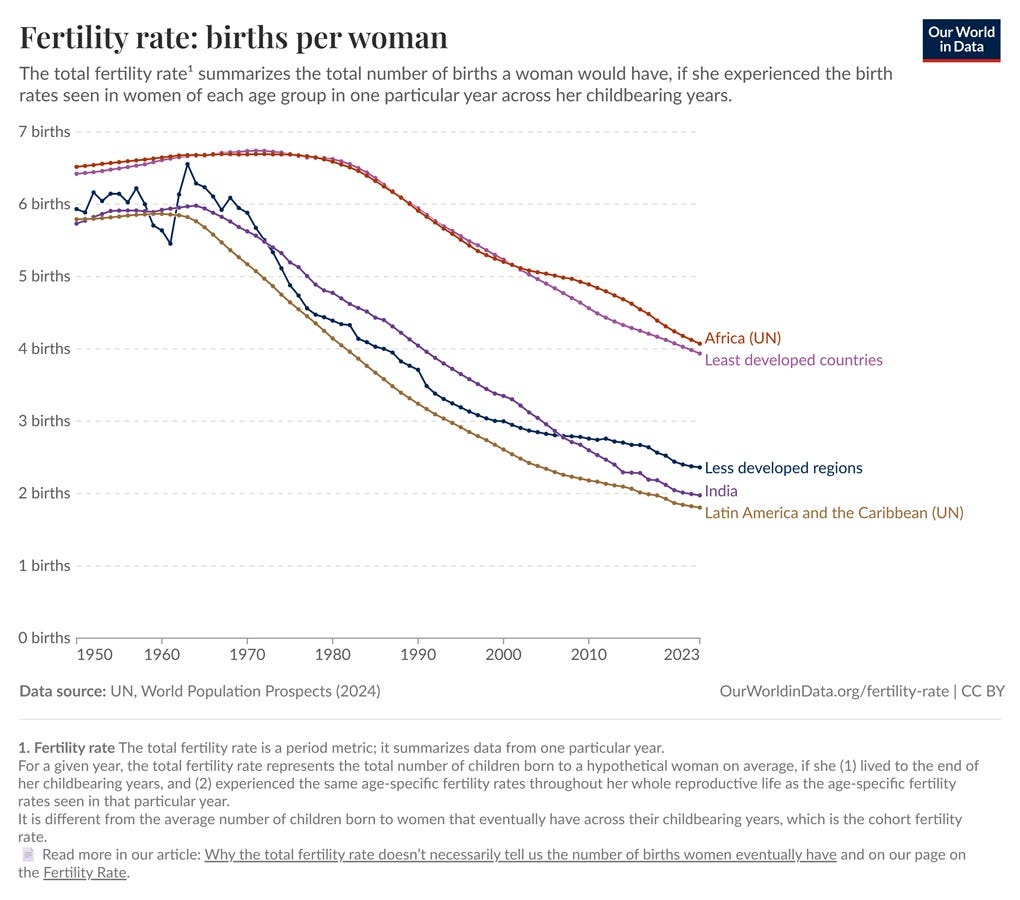

But this isn’t a post about China; it’s about the whole world. Those who expect China’s low fertility to end its bid to dominate the globe are in for a severe disappointment, since fertility is falling in the rest of the world as well. It’s true that China is an especially severe case — a TFR of less than 1.0 puts it in a special category with Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, and Thailand (Japan, interestingly, is still slightly higher). But over the past decade, fertility has begun collapsing all over the world, much faster than it had been declining before.

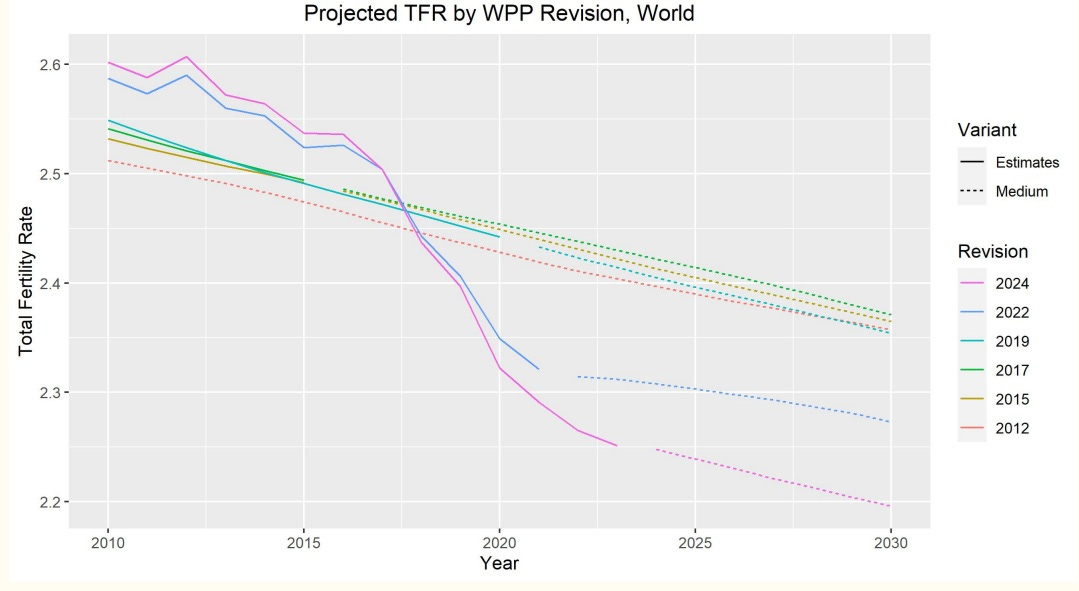

Fernández-Villaverde has a good set of slides from 2023 explaining why the new fertility crisis is different and more urgent than traditional concerns. In earlier times, fertility tended to gently decline in each country until it was just under the replacement rate — the kind of baby deficit that seemed like it could be fixed with reasonable policies. But since the mid-2010s, the fertility decline has accelerated, and there seems to be no bottom to the new collapse; every year, statistical agencies revise their already negative projections downward even more.

When they confront these stark numbers, there are several things that people tell themselves (or shout on social media) to try to cope with the notion of a shrinking humanity. I’ll go through the most common of these coping statements, and explain why each of them is wrong.

1. “The only thing that matters is per capita living standards, so a shrinking population is fine”

People who say this forget that a shrinking population is also an aging population. Old people can work longer, but eventually their bodies and minds break down and they need to be supported by younger workers. Here’s what I wrote in 2024:

[With an aging population] every working-age adult has to toil harder and consume less in order to support a growing number of people who are too old to work…In the 1990s and 2000s, there were more than 5 working-age Americans (age 15-64) for every elderly American (64+). By 2021, there were fewer than 4. That means that the economic burden of supporting each elderly American is now shared among only 4 people instead of 5…And in other rich countries, it’s even worse. In France, there are only 3 working-age people for every elderly person. In Japan, there are only two[.]

And here’s what I wrote in 2023:

[A] shrinking population means that profitable investments will be a lot harder to come by…[I]f there are more old people and fewer younger people, then demand for the assets of the old is going to have to be split among more sellers. And that will mean a lower price. In other words…people will have to save more and more during their working years in order to make it to a comfortable retirement.

And here’s the upshot:

So in general, the shrinking world will be a world of toil. Working people will have to bear the burdens of higher taxes, more eldercare, and longer working lives. And despite working more, they will have to be thrifty and ascetic, saving more money for their own retirements.

On top of all this, a shrinking population creates a problem for physical infrastructure. Road systems, sewer systems, electrical grids, and so on were built to support a certain size of population; cut the population in half, and there won’t be enough people to support all that infrastructure in any given area. We tend to forget just how quickly human structures depreciate and fall into ruin, and how much human maintenance they require to remain usable.

You can try to consolidate people into fewer towns and smaller areas, but human mobility is not infinite; some people will be stuck in decaying towns, rotting away in despair.

2. “Productivity improvements will compensate for shrinking populations”

It’s true that if you raise total factor productivity, it will compensate for a shrinking work force. But there are three big problems here. The first is that with a few exceptions, every country is already trying as hard as it can to raise productivity, so there’s no button you can press that says “raise productivity even more” when your labor force starts to shrink.

The second problem is that shrinking workforces also shrink the number of people who are available to work on improving productivity. Chad Jones models this out in a 2022 paper, which shows some potentially dire consequences from a shrinking pool of researchers.

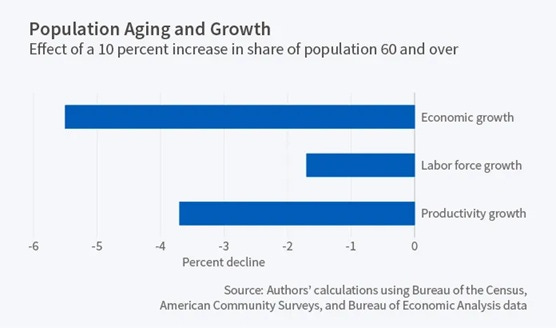

The third problem is that aging populations tend to have lower productivity growth:

And this is from Ozimek et al. (2018):

The aggregate data show a clear relationship between an older workforce and lower productivity at the state-industry level, in both cross-section and panel models. The results are confirmed using employer-employee linked data…that show having older coworkers reduces an individual’s wages.

So low fertility will actually make it harder to raise productivity to compensate for low fertility.

3. “Robots will make human workers unnecessary anyway”

I encounter this one a lot these days. But this is also a coping statement rather than a solution. For one thing, we have no idea if it’s true or not. So far, AI systems are able to do some things very well and other things not very well, meaning there’s still a lot of need for human labor.1 That might change — we might develop AI systems that do everything well, allowing technology to replace labor instead of complementing it. But we don’t know if we’ll be able to do that, and it’s foolish of us to place all our hopes in that one possibility.

On top of that, total replacement of the human labor force with AI would just be a different kind of posthuman future. It would be an incredibly disruptive event for societies as they are currently set up. At the very least it would require massive labor reallocation of the type that we haven’t proven very good at in the past, creating a vast dispossessed underclass almost overnight. It could also drive up prices for electricity, land, and water to the point where humans are essentially driven to starvation, requiring large-scale redistribution of capital income in order to keep the human population alive. That would disrupt every political system on Earth, possibly causing disruptions more severe than occurred during the Industrial Revolution.

In other words, this is not a scenario to comfort ourselves with.

4. “Concerns about low fertility are racist and sexist”

When I warn about low fertility on social media, I inevitably encounter a few progressives telling me not to worry, because:

Concerns about low fertility are actually just concerns about low white fertility, and

Concerns about low fertility are excuses to enslave women and turn them into baby-making machines.

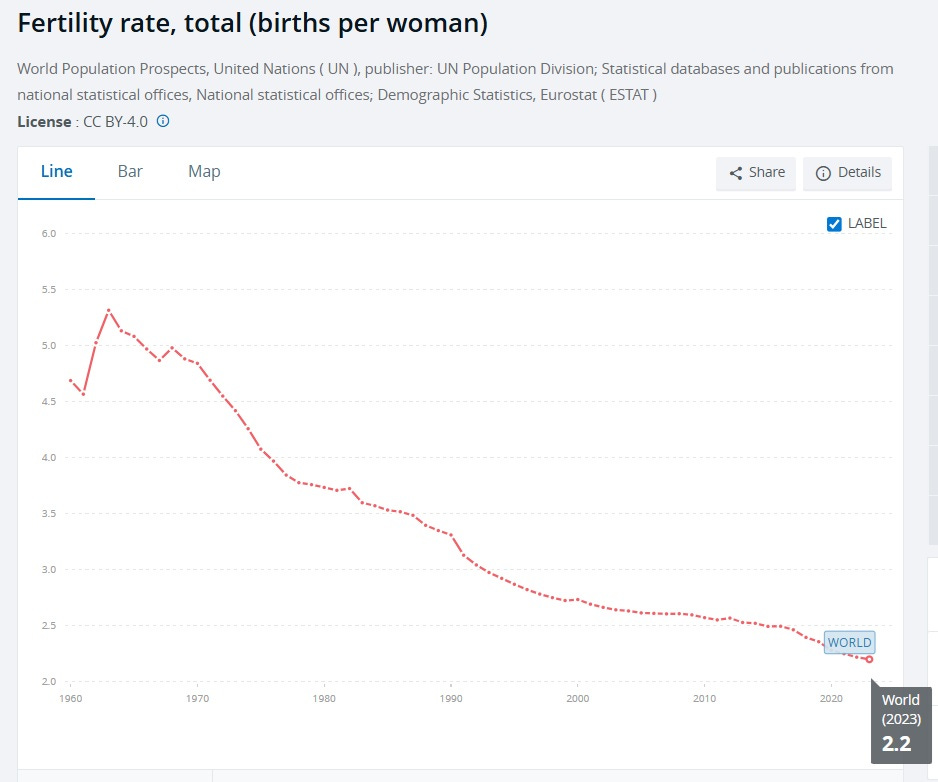

The first of these is just flat-out false. Asian fertility is lower than white fertility, for one thing. But fertility rates are also collapsing at an accelerating rate throughout the entire world, including Africa, Latin America, India, and poor countries in general:

As for sexism, I haven’t seen anyone contemplate turning society into The Handmaid’s Tale, and even deeply religious Muslim countries have seen stark fertility decline. So enslaving women doesn’t seem to be on the list of policy responses to the population crisis.

5. “We can just pay people to have more kids”

Paying people to have more kids does “work”, in the sense that people do have more kids when you pay them to do so. The problem is that they don’t have very many more kids; the effect sizes are so small that the amount of money required to boost fertility to near replacement levels would be prohibitive.

China has been trying to boost fertility with economic support for years, with no apparent result. Hungary tried to pay people to have more kids, with no lasting results at all. South Korea implemented a very substantial “baby bonus”, equivalent to about $700 per month, and it had the effect of reducing the fertility decline by 4.7% — not nearly enough to offset the catastrophic declines of recent years.

Even under optimistic assumptions, the sums of money required to restore non-collapsing fertility through baby bonuses are astronomical. This is from Lyman Stone, who studies this issue:

In 2020, the total fertility rate is probably around 1.71 children per woman. Thus, to reach 2.07, we would need a 21% increase in birth rates. To accomplish this, we would need the present value of child benefits to increase by somewhere between 52% and 400% of household income. For the median woman, this would mean providing a child benefit for the first 18 years of a child’s life worth approximately $5,300 per year in addition to currently-provided benefits, with the range running from $2,800 more per year to $23,000 more per year.

$23,000 per year, or even $10,000 per year, is an incredibly large sum of money — much more than any current welfare proposals, and enough to require gargantuan tax hikes that would no doubt prove politically toxic. But even this would not be enough — not even close.

Since Stone wrote that post, the U.S. TFR has fallen again, to 1.62. There is no reason to think it won’t fall more. This means that even under extremely optimistic assumptions about the power of baby bonuses, the amount we’d have to pay to get fertility back up to near replacement is just a complete political non-starter. For countries like China and Korea, the gap is far greater still, and baby bonuses are looking like they have only a very small effect.

Back in 2012, there were policies available that might have raised fertility to sustainable levels in many rich countries. As of 2026, in the face of the catastrophic and ongoing acceleration in the fertility decline, we have no known policy capable of addressing the problem.

6. “Immigration will solve the population problem”

Immigration is good, but sadly it won’t solve the population problem. First, fertility is falling across the entire world, even in the poorest countries of Africa. In the world as a whole, fertility rates are approaching replacement level and may already be there.

There is no other planet to get immigrants from.

Rich countries, of course, can continue to dull the pains of population aging and shrinkage by taking people from poor countries. But as Fernández-Villaverde notes, it’s not that simple, because those rich countries have strong welfare states. Poor immigrants are going to use lots of welfare benefits, ultimately canceling out much of their economic contribution to the nation. And because immigrants themselves age, they’re eventually going to contribute to population aging, especially because many of them come when they’re already middle-aged.

So anyway, there is a massive amount of coping on this issue, because people see a grave and possibly even existential threat coming inexorably in their direction, and they don’t think there’s anything they can do to stop it, so they need something to tell themselves in order to stop worrying. But this sort of self-reassurance won’t solve the actual problem or avert the actual threat.

In fact, we mustn’t bury our heads in the sand on this issue, or tell ourselves that it’s all going to work out. Instead, we have to face up to the problem, so that we can start looking for ways to solve it.

What we need right now is research, research, and more research

Humanity has always relied on technical solutions to get us out of our worst problems. It was research into green energy that has given us hope of stopping climate change. Vaccine research has given us hope of stopping pandemics. The Green Revolution staved off mass starvation from population growth, and so on.

Collapsing fertility is a bit different from those other problems, because it’s fundamentally a social problem rather than a physical threat like climate change, disease, or starvation. Social science research is typically much more expensive and much less conclusive than research in the physical sciences.

But despite that big hurdle, it stands to reason that the human race should be doing lots and lots of research on how to avert this imminent and nearly existential threat. I propose a Fertility Policy Research Center, gathering together top researchers in experimental economics and development economics, epidemiologists, quantitative sociologists, and so on. The goal would be to find a solution to the problem of long-term stabilization of the fertility at or near the replacement rate of 2.0.

The center’s activities could include:

Epidemiological and observational research on the causes of fertility drops

Randomized controlled trials of policy interventions to raise fertility

Trials of technological interventions for increasing fertility

The first and third of these won’t be that expensive. It’s the second of these — RCTs for policy interventions to raise fertility — that will cost a lot of money and take a lot of time. A single study can cost millions of dollars.

The funding for fertility policy research will thus have to be in the billions of dollars. That’s outside of the range of modern philanthropic research, but not by much — the ARC Institute has pledged grants of $650 million, and CERN’s Future Circular Collider has $1 billion, all from private sources. It’s not out of the realm of possibility that a group of billionaires might be willing to pool their resources and endow a Fertility Policy Research Institute with $5 billion or even $10 billion.

Take Elon Musk, for instance. The world’s richest man has clearly identified ultra-low birth rates as an existential threat:

Musk’s net worth is now over $750 billion. Just one percent of his wealth could fully endow a Fertility Policy Research Center with all of the money it would likely need for at least two decades. Five percent of his wealth could endow the center with all the money it would ever need. Isn’t solving an existential threat worth five percent of one man’s wealth?

Anyway, there is no dearth of hypotheses to consider here. Big questions for the research center might include:

Is social media causing the recent acceleration in the decline of fertility rates? Would restrictions on social media use be sufficient to raise TFR by a significant amount?

Does geographically concentrating people with high fertility rates tend to increase or decrease society-wide birth rates?

Does living space per person affect fertility rates?

How does economic security affect fertility rates?

Which is more cost-effective for raising fertility: cash payments or in-kind benefits like free child care?

Would AI nannies or tutors relieve some of the burden of child care, thus increasing people’s desire to have children?

How do maternal and paternal leave affect fertility rates?

Does gender equality in household chores affect fertility?

How do norms of higher and lower fertility get transmitted? Can these norms be influenced by deliberate media campaigns or other informational interventions?

Are there interventions that encourage couple formation earlier in life?

Are there any public health factors affecting fertility rates to a significant degree?

These are just a few hypotheses off of the top of my head. Putting $50 million toward investigating each of these would use up only 0.065% of Elon Musk’s wealth, while the payoff from even one important, usable finding could be absolutely huge.

It would be even better, of course, if governments could get involved with the funding effort. This could be tricky, since government grants usually go through laborious and slow processes. In the U.S., a special research project — similar to the Human Genome Project — might be able to circumvent some of those procedural hurdles. And since fertility decline is such a worldwide problem, there are probably plenty of governments who would contribute some funding to the center — many without onerous red tape. China, in particular, seems like it would want to fund a crash program for solving the birth rate problem.

Government support will be especially crucial when scaling up policy interventions from RCTs to actual government policy. This can be very tricky and very expensive, since many interventions don’t scale up. Government support, both logistical and in terms of funding, would often be essential — but it would also probably be forthcoming.

It’s kind of insane that nobody has done this yet, and it speaks to the power of the six coping statements that I listed above. A lot of people have managed to convince themselves that the problem of low fertility is no big deal, or that it’s easily solved, or that even viewing it as a problem is illegitimate. They are all wrong. It’s a huge problem, and we need to be attacking it with the same tool — scientific research — that we’ve used to defeat so many adversaries in the past.

This is a stochastic version of Moravec’s Paradox.

Great list of research topics. I would add: would it help to call it "child rearing policy," not "fertility policy," because the real problem is the daunting task of child rearing. "Fertility" doesn't get at the actual labor. Ask any grandparent who is doing substantial child-rearing work. (My hand is raised.) Everyone I know who is not having kids will tell you: parents fear the grueling, 18+year long task of doing a good job, when the world is watching, when once you're in you can't back out.

Musk's solution to declining fertility rates so far has been rather more direct than funding research into the problem.