Humanity is going to shrink

No one has any idea how to stop the decline, so we need to prepare for the consequences.

The problem with population growth projections is that they naturally follow an exponential curve. When “like begets like” — when the number of kids is just proportional to how many people are currently alive to have kids — you get a function that either explodes to infinity or decays to zero as time goes on. So no matter what the fertility rate is, humanity is always on course for either runaway overpopulation or an empty planet…if you project far enough into the future. Exponentials are inherently unstable.

That said, the farther the total fertility rate gets from the “replacement level” of about 2.1 live births per woman, the sooner the big population changes will occur. And lots of countries that demographers had previously predicted to stabilize somewhere close to the replacement rate are starting to drift toward seriously low birth rates.

For example, China. With 1.4 billion people, China accounts for 17.5% of the global population. For years the government claimed that fertility was around 1.7, but those numbers were probably being faked. Not only was the true number lower, but it’s fallen precipitously in recent years. Right now it’s around 1.09, which is among the lowest in the world.

Or take the U.S. For years, our fertility rates seemed to defy gravity, hovering at or even slightly above the replacement rate, and prompting lots of triumphalist long-term projections. But much of this was due to high teen pregnancy rates and the high fertility rates of recent immigrants, which both diminished in the 2010s. Our TFR stood at 1.66 in 2021 according to the UN (though some sources have us a bit higher). The number of babies born in 2022 was 15% below the number born in 2007.

Finally, there’s Africa. With a total fertility rate of 4.3, it’s the one continent that’s still above replacement. But it’s headed in the same direction as everyone else. Here’s a graph for Africa as a whole, and the 8 most populous countries:

Other sources have these countries at even lower rates, and the other sources may be right. As a recent Economist article noted, every time demographers go take careful measurements in big African countries like Nigeria, they’re surprised on the downside. Africa’s population is still going to rise a lot thanks to population momentum, but hopes that it would defy the general trend toward childlessness appear increasingly far-fetched.

The whole world is heading toward negative population growth. Immigration can help specific countries (especially the U.S.) maintain their populations for a while at the expense of others, but as the whole world converts to small families, even that stopgap solution will become less feasible.

This doesn’t mean that the human race will inevitably shrink to a small dying remnant of childless old people, huddling together for one last bit of companionship as nature or our AI descendants take over the planet. That scenario is science fiction, since it requires projecting very very far into the future. But the global fertility collapse will have big enough implications in the short term that it’s worth preparing for.

So let’s talk about some of the effects of our low-fertility future, and then afterwards we can talk about how we might change things in the long term to avoid those scary sci-fi scenarios.

A shrinking world is a world of toil

We don’t entirely have to imagine what a shrinking world will look like, since some countries are there already. Japan is the oldest country in the world; half of its people are over 49. Its population began decreasing gently in the 2010s, but more importantly, its working-age population peaked in the 90s and has fallen by about 15% since then:

I’ve been going to (or living in) Japan for about 20 years now, and the change is palpable. Youth culture has waned, and the cities are choked with old people. Japanese people, already straining under an unproductive corporate culture, have to work ever longer hours to support their aging parents. Despite the country’s efficient, cheap health care system and meager pensions, taxes have had to rise to fund both, simply because of the age ratio. Meanwhile, the ranks of corporate management are clogged with people in their 50s and 60s, making it hard for younger people with new ideas to change anything or get ahead.

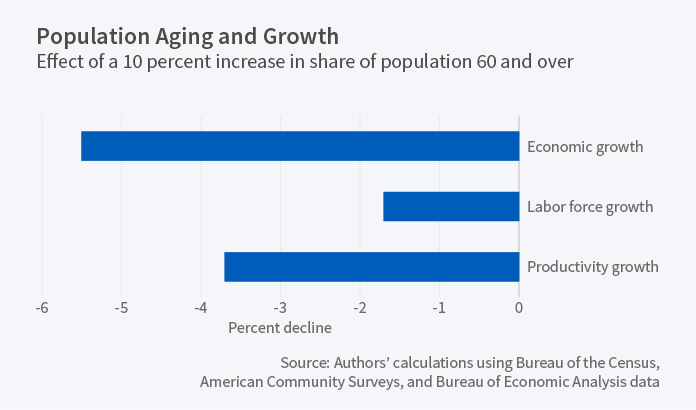

Researchers aren’t in complete agreement, but the general preponderance of evidence seems to suggest that aging exerts a persistent drag on rich economies — not just through a greater proportion of retirees, but via lower productivity growth. Here’s a graph of what that might look like, from a paper that I think does a particularly good job of isolating the causal impact of aging, by looking at the impact of demographic factors that were “baked into the cake” long ago:

These numbers might be a little confusing, so let’s unpack what this means. In 2000, ~16% of Americans were over 60; by the late 2020s this is projected to be around 24%. That’s about a 50% increase in the percentage (sorry, I know that “percent of a percent” is a bit confusing). So according to these estimates, that means the U.S.’s total labor productivity increase over that time frame would be expected to be about 18.5 percentage points lower due to aging. Given that it’s just the early 2020s now, and labor productivity has already increased by about half since the year 2000, an 18.5 percentage point drop is substantial but hardly crippling.

And this pattern — a substantial but not crippling economic drag — is exactly what we see in Japan. Though the picture I painted above sounds bleak, Japan is still a wealthy country and, except for the long working hours, a nice place to live. Of course it’s not clear how long that can go on; maybe there’s some point where aging’s deleterious effect on an economy starts to become overwhelming, and the nation collapses into poverty. But if that point exists, we haven’t found it yet.

There will also probably be macroeconomic effects. Most macroeconomic models predict that as the population shrinks, the “natural rate of interest” goes down. The “natural rate” is a theoretical construct — the idea is that if the actual interest rate is above the natural interest rate, it pushes inflation down and leads to unemployment. So if the natural rate goes way way down, that makes it harder for central banks to keep inflation above zero; inflationary episodes like the one we just had will be rarer and less severe, and we might find ourselves dealing with low-rate, low-inflation situations like the 2010s more often. (Of course, that’s all just theory, and as we know, macro theories are not particularly reliable…but except for the current episode, interest rates have already been falling for a long time now.)

Financially, a shrinking population means that profitable investments will be a lot harder to come by. Lower economic growth means less earnings growth, less demand for real estate, and so on. Intuitively, asset price appreciation is about transferring wealth from the young and middle-aged (who buy assets) to the old (who sell them) — if there are more old people and fewer younger people, then demand for the assets of the old is going to have to be split among more sellers. And that will mean a lower price. In other words, your ability to get well-off just by sticking around and getting old will be much reduced; people will have to save more and more during their working years in order to make it to a comfortable retirement.

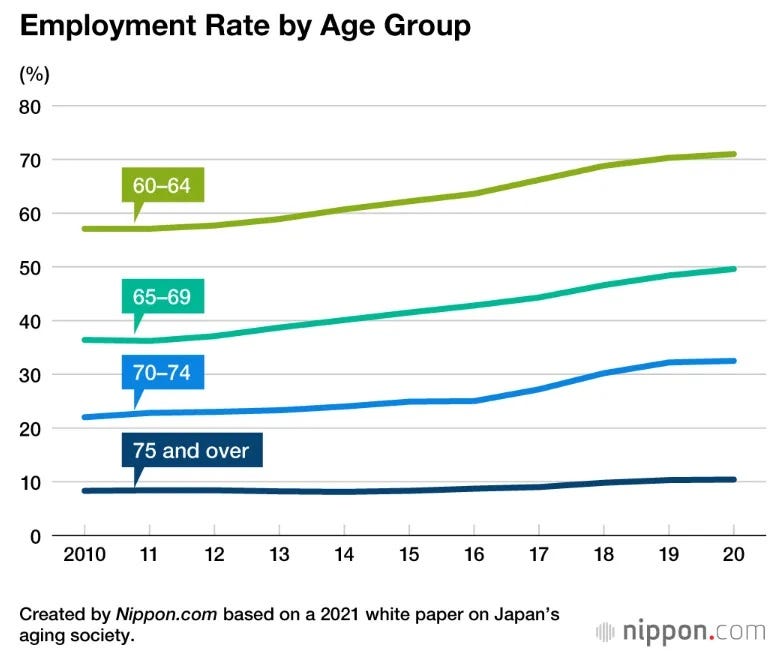

And that retirement will be further away. Japan shows that one reliable effect of population aging is that people work longer into old age:

(Only a very small amount of this is from increases in life expectancy, which have pretty much topped out.)

So in general, the shrinking world will be a world of toil. Working people will have to bear the burdens of higher taxes, more eldercare, and longer working lives. And despite working more, they will have to be thrifty and ascetic, saving more money for their own retirements. The age when young people could afford to be idle and “find themselves”, because asset appreciation and the economic benefits of a youth bulge would deliver them wealth for free, will gradually fade into memory.

Obviously many of us hope that AI and robotics will ride to the rescue and automate away much of this drudgery. That’s an outcome that lots of people are currently afraid of, because they’re afraid AI will take their jobs. But when you compare a future of automation with a future where the young toil grimly until age 74, the former looks a lot less scary. And in fact, some researchers do believe automation will ameliorate the burdens of a shrinking population. So, fingers crossed. But AI would have to replace labor a lot more quickly and completely than information technologies have up til now; it could happen, but I’m not counting on it.

Now, I’ve been listing negative effects of population shrinkage, but it’s important to remember that population decline has some unambiguously good effects as well. The main one is a reduced strain on natural resources. Yes, the degrowthers are wrong, and we can grow the economy while also reducing our natural resource footprint. But that job becomes a lot easier if population growth is lower — essentially it’ll be easier to generate per capita growth if it has to be spread among fewer people. That will cancel out some of the negative effects of slower productivity growth, and it will also help return some of the planet to the plants and animals that we’ve been pushing to extinction as we encroach on their habitats.

If I had to describe what a shrinking world will look like, a metaphor I might use would be a lovely pastoral farm attached to a giant retirement community, where the young people have to toil hard in the fields but manage to get enough to eat. That’s a caricature, of course, but I think it captures the basic changes, and in some way it’s a decent metaphor for what’s already happening in Japan.

How can we stabilize the population in the long term?

Now, what I just described is just what I think will happen over the remainder of this century. Project far enough out, and those exponential curves work their relentless magic, and things start to get really scary for humanity — at some point there might just not be enough young people left to support modern standards of living. So although it’s almost certain we won’t be able to stop population decline from setting in, we should still be thinking about how to reverse it at some point.

Going back to the basic math, remember that every exponential curve either grows or shrinks without limit; exponentials are unstable. And population growth is always exponential, because people are what produce more people. So the only possible long-term solution is active stabilization — we need policies that decrease fertility when it’s a little above 2.1, and raise fertility when it’s a little below 2.1.

We already have the former. We know we can decrease fertility by making birth control more available, increasing urbanization, and incentivizing people to stay in school longer (which delays family formation). What we don’t have is the latter — no one on the entire planet has ever come up with a reliable way to persuade people to have more than 2.1 kids.

Countries have been trying pro-natalist policies for many years now, and we have a decently sized body of evidence on their effects:

Here is a 2019 review by the UN

Here are articles by Elizabeth Brainerd and Lyman Stone reviewing what we know.

The basic story here is that at least one type of pro-natalist policy works, and possibly two. The kind that we’re pretty sure is effective is having the government provide universal free child care. Taking the burden of child care off of people’s hands, and doing it in a reliable predictable way, means that the prospect of kids doesn’t mean the prospect of yet more toil and drudgery for working-age people. The policy that we’re starting to realize might be effective is parental leave.

The problem here is that these policies, despite being expensive in both fiscal and labor terms, are only mildly effective at raising fertility. We’re talking about increasing the birth rate by a few percentage points. That might be enough to actively stabilize the long-term population if fertility were, say, around 1.9. With fertility around 1.6 it’s not going to make a huge difference, and with fertility at less than 1 it’s just a drop in the bucket. We should definitely do these policies, but we shouldn’t expect huge improvements.

The grim truth appears to be that human beings just inherently don’t want that many kids. Remember that lots of kids are accidental; people in the old days just had sex because it was fun, and kids were the inevitable eventual result of that. With the advent of birth control (not just the pill but many methods), safe abortion, and information about how to plan families, people are able to have sex without accidentally having kids. So most of the kids we have now are intentional.

You can ask people how many kids they’d like to have, and often you get a number that’s higher than the number they actually end up having. American and European women in the mid-2010s said that they’d like to have about 2-2.5 kids on average, but ended up having fewer. Now, I don’t necessarily trust these surveys to get the exact numbers right. The general public probably sees having more kids as a good thing, causing people to overstate their actual desires a little bit — a type of survey error known as “social desirability bias”. But it is true that the very richest households — those making more than a million a year — do have somewhere between 2 and 2.5 kids per woman.

So maybe the surveys are right! But per capita GDP is more than an order of magnitude less than a million dollars, so there’s physically no way to make everyone that rich; in other words, alleviating resource constraints with pro-natalist policies to the point where fertility actually rises above the replacement level is perhaps possible in theory but not possible in practice.

That leaves humanity with a few other options, short of returning to a pre-industrial state. All of them sound like speculative fiction, but this is the long term we’re talking about, so they’re worth thinking about.

One option is to invest very heavily in child care technology, to make the job of taking care of kids as easy as possible. This could potentially even include “womb tanks”, like in a Lois McMaster Bujold novel. Perhaps over time that will decouple child-bearing from the expectation of toil and drudgery in prospective parents’ minds.

Second, we could attempt social engineering. New living arrangements could allow people to raise children collectively, reducing the burden of child care. Communities of people who like kids might create pockets of high fertility. This traditionally happens in strict, closed-off religious communities, but those communities aren’t very stable in the age of the internet (because they’re not really the best places to live). A friendlier, more modern solution might be the Japanese town of Nagi, where people who really like having kids move to be close to each other and reinforce each other’s life choices. Intentionally creating more cities where the people who naturally love children can move to be around each other might generate high-fertility nuclei that could send some of their surplus kids to work in the rest of the economy.

If all of those sci-fi options fail, then we may have to simply wait for the human population to collapse. We may inevitably become such an aged society that our economies collapse as well, returning us to pre-industrial poverty and beginning the cycle all over again. Or something weirder may happen — the ubiquity of birth control might cause humanity to rapidly evolve into a species that just really really loves being around children, since only the people with some sort of deep innate love of kids will choose to have lots of them. That might be the best long-term outcome of all, from a humanitarian standpoint. But at this point this blog post has gotten wacky and speculative enough, so I think I should leave it at that.

In the meantime, prepare to live out the rest of your life on a swiftly aging planet.

> the ubiquity of birth control might cause humanity to rapidly evolve into a species that just really really loves being around children

This is how population growth accelerates. In the next generation, a higher proportion of kids come from families with 3+ kids. As long as propensity to have more kids is somewhat heritable, when those kids grow up they have more kids than average, and their fraction of the population grows further. Over time, people with a propensity to have more kids become more and more common.

In evolutionary terms, the invention of birth control created a massive selection effect in favor of desire to have kids intentionally, and removed any benefit of traits that produce kids accidentally. Birth control is new enough that evolution hasn't caught up yet.

Propensity to have kids could come from really really loving kids for their own sake, or from an ideology that favors big families (as in some religious communities), or some other effect I can't think of. Whichever reason is most heritable should grow over time in the human population - I hope that really really loving kids will be the answer.

Hey Noah, one thing that's also likely to drive up fertility rates is just being more open to different family arrangements as a society. The correlation between the share of out-of-wedlock births and fertility rates is almost perfect for OECD countries: countries with more traditional family arrangements (as reflected in a lower share of out-of-wedlock births) consistently have lower fertility rates. This is importante because many politicans in the West that are purportedly worried about shrinking populations (like Giorgia Meloni) cannot come with any proposal other than persecuting non-traditional families, which the evidence says are the ones that still can drive births higher. It just points out the whole hypocrisy of the "traditional" family arguments, which by the way want everyone of us to think that a working heterosexual couple living in a small apartment can count of as "traditional".