The giant basket case countries

More and more of humanity is going to live in a few big countries that can't manage themselves.

I used to talk a lot about developing countries — how the successful ones accelerated their growth, and what lessons the others could learn from those successes. Here’s a whole series I wrote about the more promising development stories:

And when I was at Bloomberg, I wrote a lot about the prospects for African industrialization (which has been disappointing in the years since), and about the need for humanitarian aid to help some of the very worst-off countries.

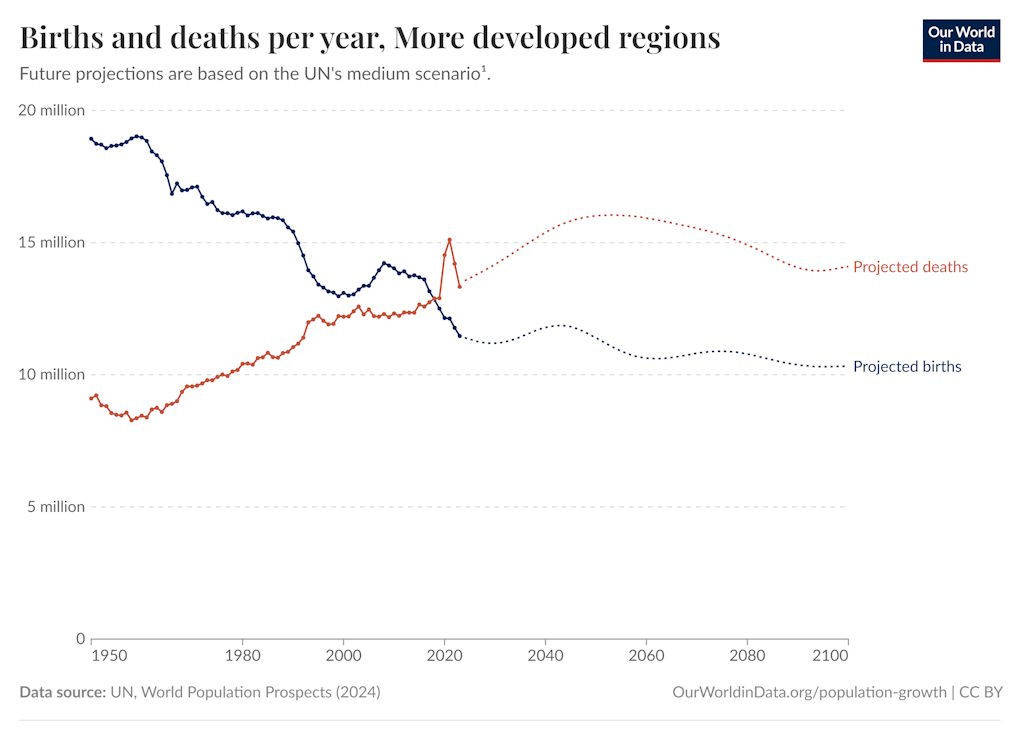

These days, I’ve been writing a lot less about developing countries, for several reasons. First of all, developed countries aren’t doing so well themselves these days — most have slow growth, stagnating or shrinking populations, and internal political turmoil. Second, with the rise of economic nationalism, there is much less appetite among rich countries for altruistic crusades to help the developing world. China did have a big idea — the Belt and Road program — but it didn’t help very much, and created a lot of problems, meaning China will also probably retreat from development promotion. Meanwhile, protectionism in the U.S., China, and elsewhere will make it harder for developing countries to pursue traditional export-led growth.

But the window when developed countries (including China) can afford to treat poor countries like an afterthought is rapidly drawing to a close. The reason is simple demographics. The whole developed world is about to start shrinking. If not for immigration, it already would be:

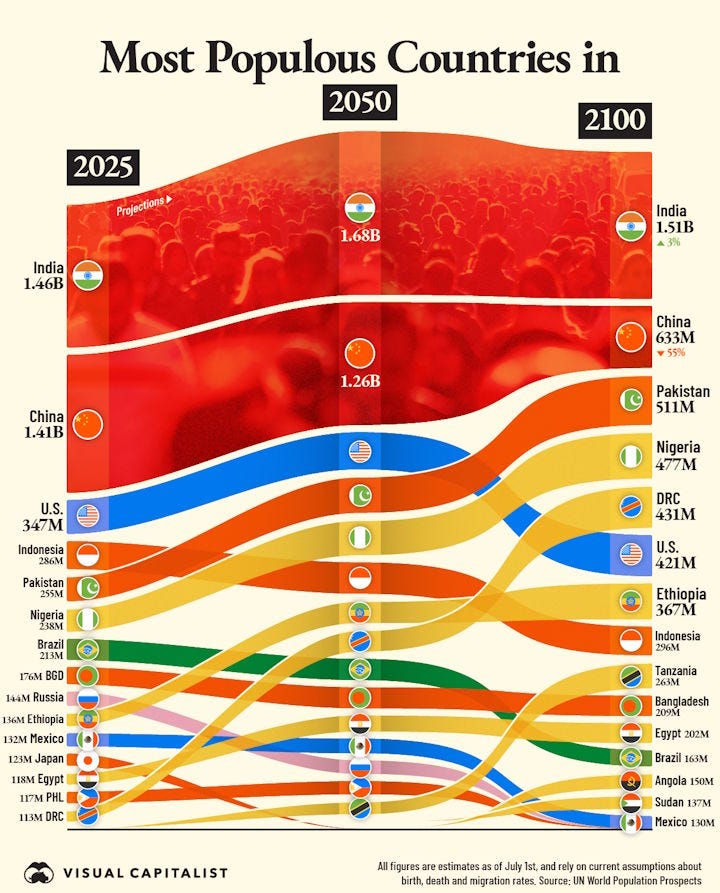

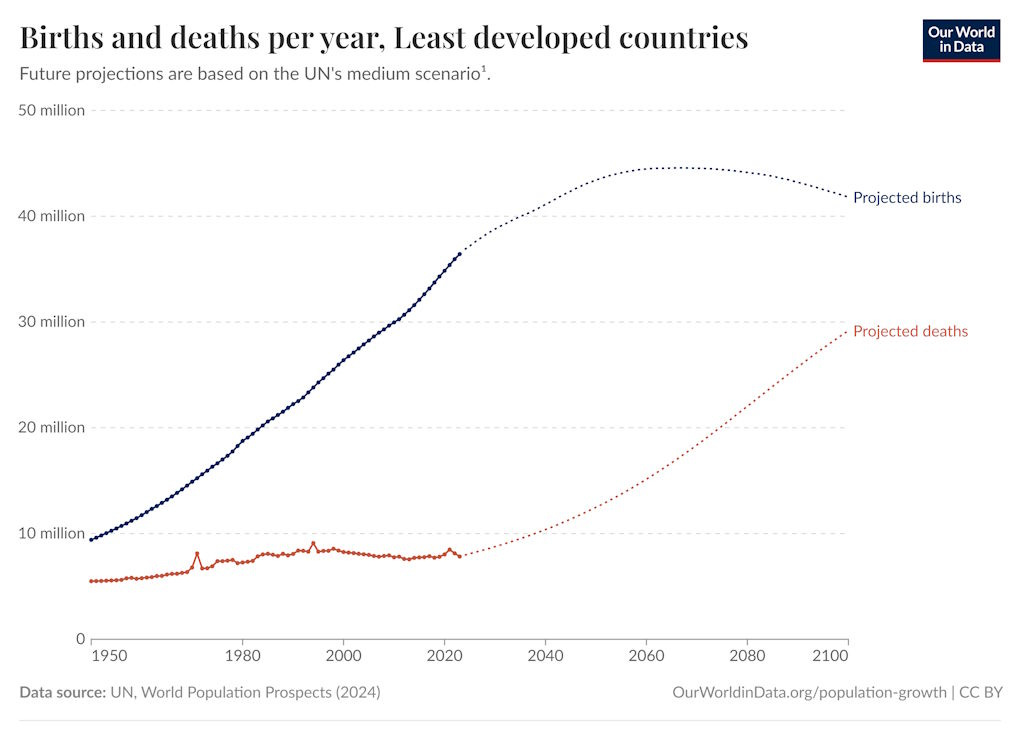

Meanwhile, the world’s poorest countries are going to experience strong population growth through the end of this century:

The result of this disparity is visible in the chart at the top of this post. By 2100, six out of the fifteen most populous countries in the world — and three of the top five — will be places that as of 2025 have under $7,000 in per capita GDP (PPP). The biggest ones will be Pakistan, Nigeria, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, with Ethiopia and Tanzania not far behind. Altogether, over 2 billion people — a fifth or more of humanity’s peak population — is projected to live in those five countries.

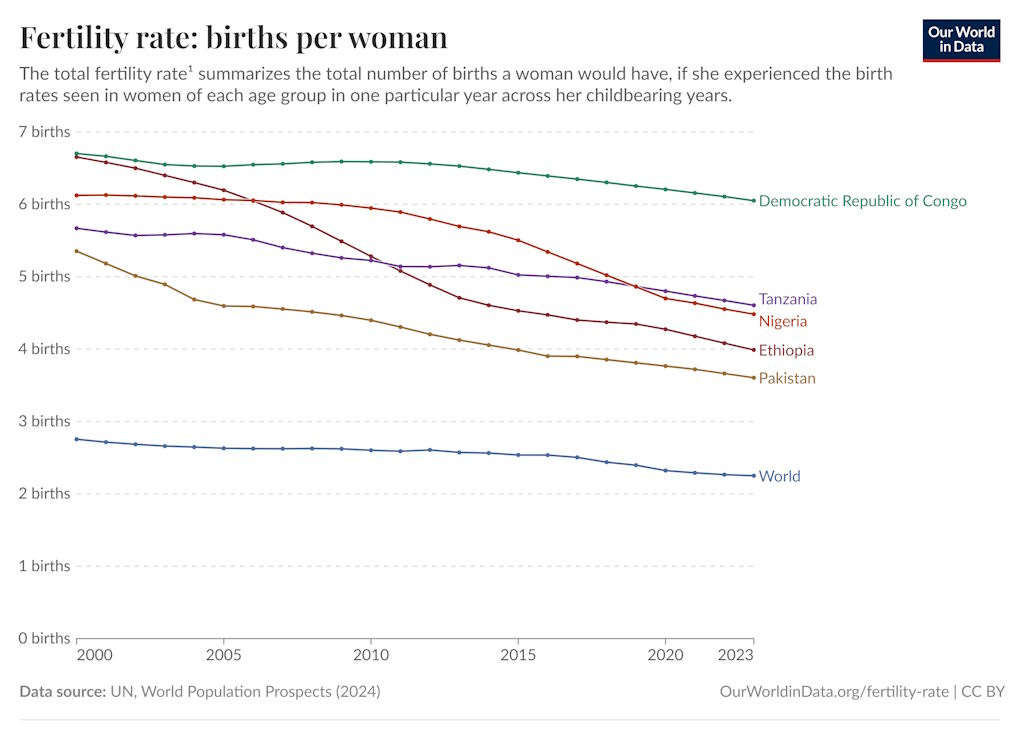

And that percentage will only grow after that, at least unless some sort of radical unexpected change happens to demographic patterns. Fertility is falling everywhere, but in the Big 5 poor countries, it’s not falling much faster than in the world as a whole:

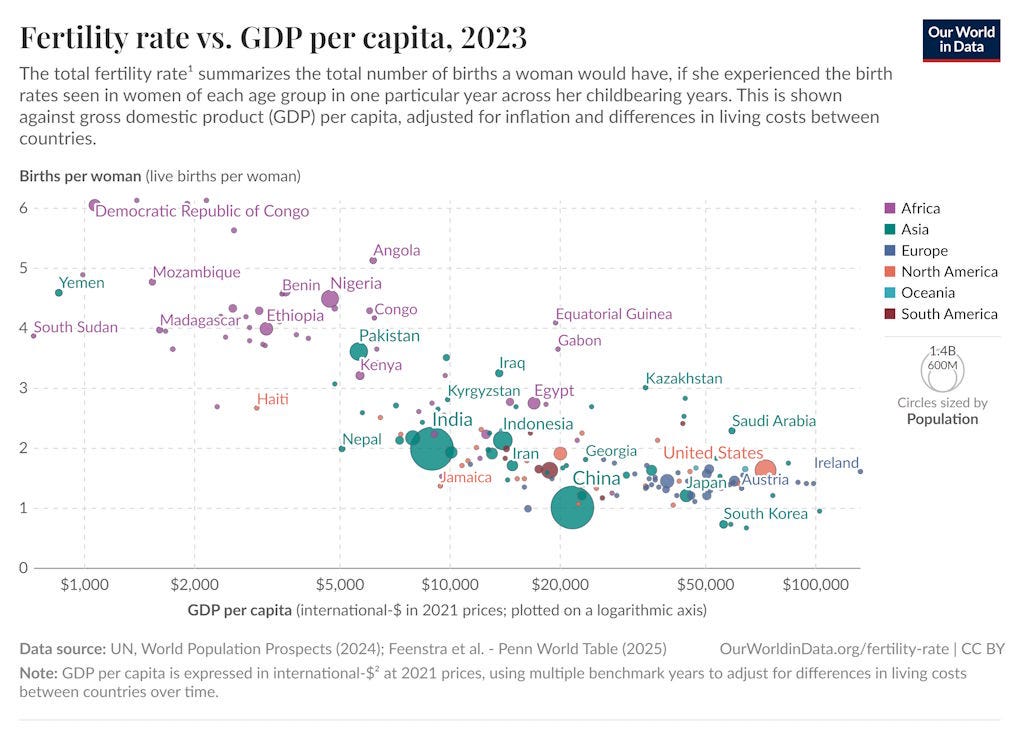

Why are these countries’ fertility rates falling so slowly? Because they’re poor. The idea that some countries are culturally resistant to the fertility transition is falling out of favor, as African nations and predominantly Muslim nations show the same pattern of fertility decline as everywhere else (or faster). But the Big 5 are unusually poor, and poor countries tend to have much higher fertility:

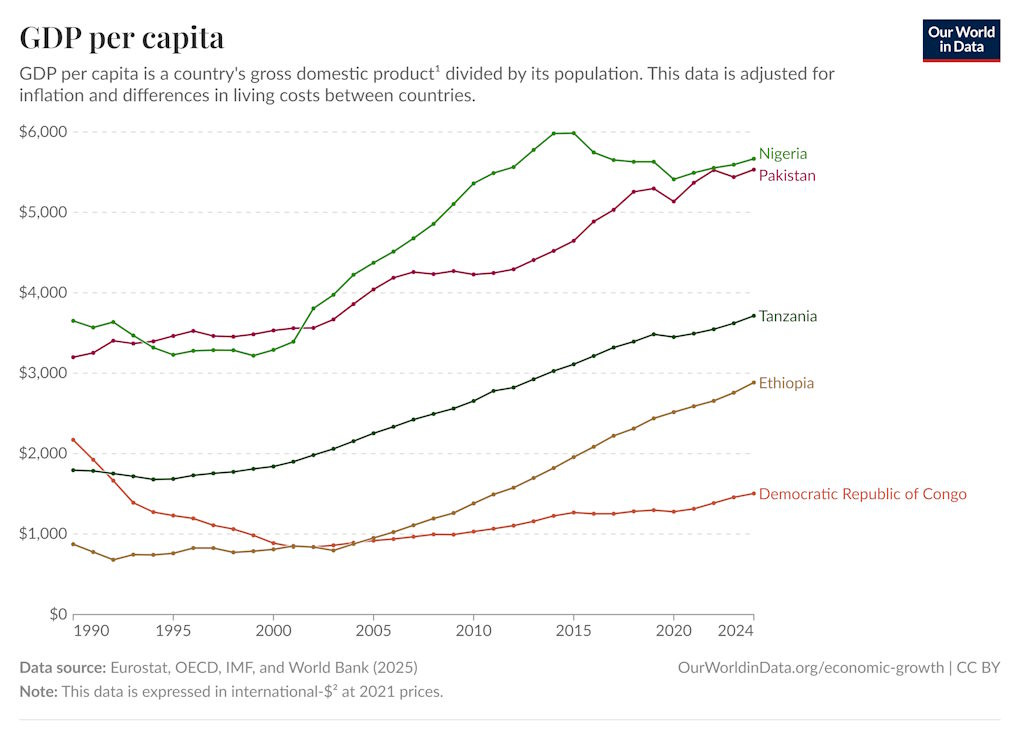

Of course we can expect to see the fertility transition accelerate as these countries cross the $7,000 threshold; as you can see on the chart, very few countries maintain high fertility past that level. But while Pakistan might manage that soon, the others probably won’t. Nigeria’s GDP per capita has actually gone down in recent years, Tanzania and Ethiopia are still decades away at current rates of growth, and the DRC is still seemingly inextricably mired in extreme poverty:

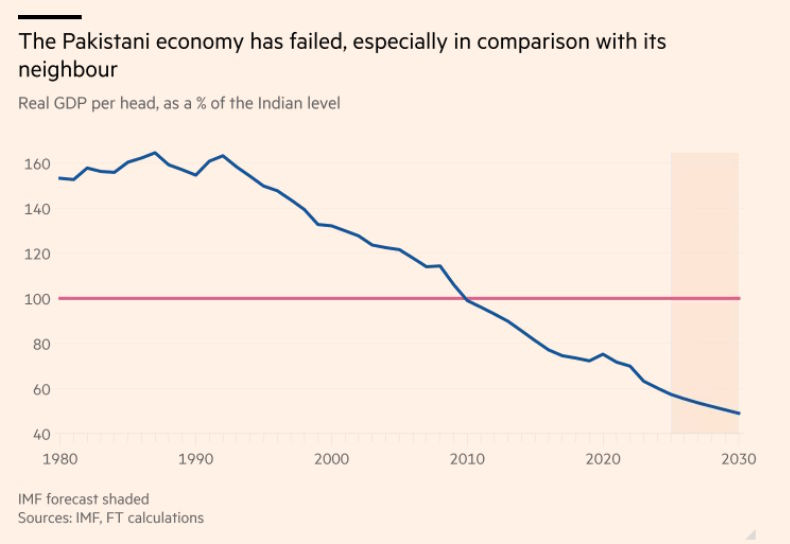

To see just how weak of a performance this is, consider the fact that Pakistan — arguably the country that’s in the best shape of the Big 5 — has fallen relentlessly behind India in economic terms:

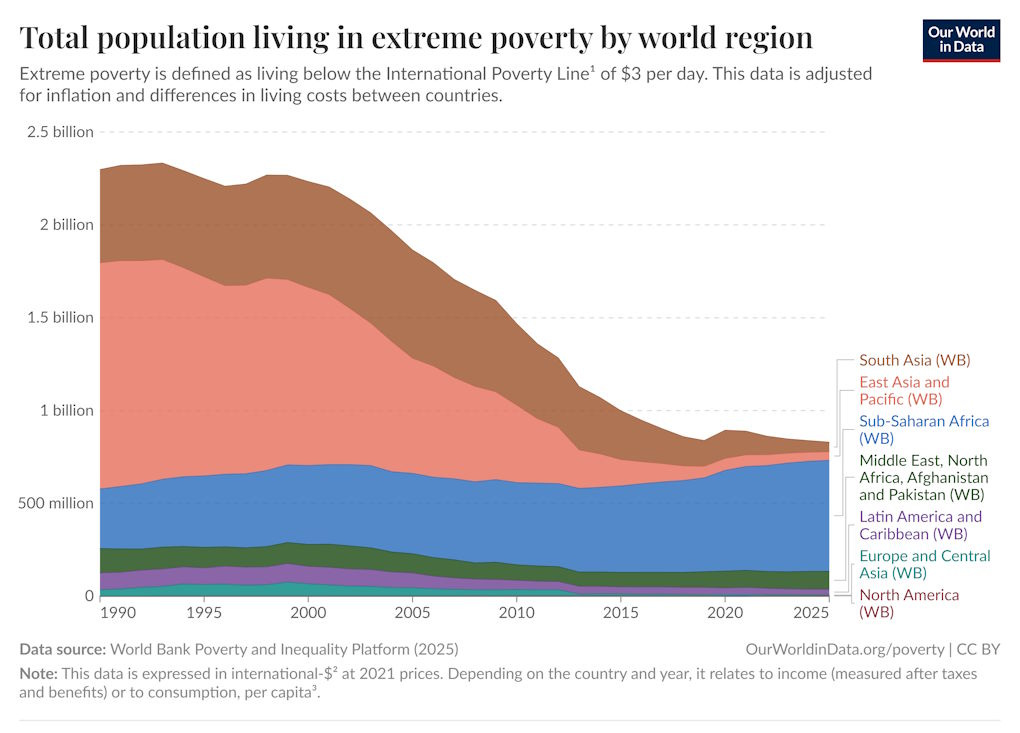

What happens to big countries is incredibly important; in recent decades, it’s India and China that have made the big strides against global poverty. These supergiant countries used to be desperately poor, but they got their act together and produced decades of solid growth — and as India and China went, so went the whole planet:

But as you can see on that chart, there’s a composition effect at work here — as big countries get rich, their fertility goes down, and their percentage of the human race falls as well. The countries with rapidly growing populations are those that failed to provide for their people. Now that Africa comprises a majority of the world’s extremely poor population, the drop in extreme poverty has stalled, and may soon start to rise again.

This tradeoff between income and fertility is a problem that the whole human race is going to have to solve, and soon, if it wants to have a prosperous long-term future. But in the meantime, poverty is still worse than aging, and the billions of people in the Big 5 poor countries deserve to have decent living standards.

And it’s not like rich countries can sit back and just ignore the suffering in poor countries, either. Emigration pressure usually peaks around $8,000 to $12,000 in per capita GDP1, meaning that rich countries in Europe, the Anglosphere, and Asia are likely to see giant waves of Pakistani, Nigerian, Congolese, Ethiopian, and Tanzanian migrants clamoring to get in. The current anti-immigration backlash gives us an unpleasant hint of what might happen as a result. Also, the shrinking of rich-country markets (due to shrinking populations) will hurt Western corporations, unless it can be matched by economic growth in developing countries.

So the world has a stake in helping the Big 5 poor countries grow. They’re highly unlikely to be the next China or India, but getting them to middle income level is probably doable.

But how? The most important thing rich countries — including China — can do is to fully open their markets to these countries’ products. The economic literature is pretty conclusive that this raises economic growth in poor countries, at least somewhat. There are many instances in which rich countries have actually done this, and there are a lot of ways we can evaluate the results of those experiments. For example, Romalis (2007) found that when America reduced its tariffs under the Most Favored Nation program, poor countries sold more products to the U.S. and grew faster as a result:

This paper examined whether improved access to developed countries’ markets raises developing country growth. The paper concludes that it does. Decreased developed country trade barriers increase developing world trade. This induced trade expansion causes an acceleration in the growth rate of developing countries. Developing countries that expanded their trade the most in response to improved access to developed country markets saw their growth rates increase relative to other developing countries…This suggests that developing country growth rates will accelerate if the developed world lowers its remaining trade barriers.

Frazer and Van Biesebroeck (2007) found that the African Growth and Opportunity Act, which opened American markets to some African products, raised African exports:

[W]e find that AGOA has a large and robust impact on apparel imports into the U.S., as well as on the agricultural and manufactured products covered by AGOA. These import responses grew over time and were the largest in product categories where the tariffs removed were large. AGOA did not result in a decrease in exports to Europe in these product categories, suggesting that the U.S.-AGOA imports were not merely diverted from elsewhere.

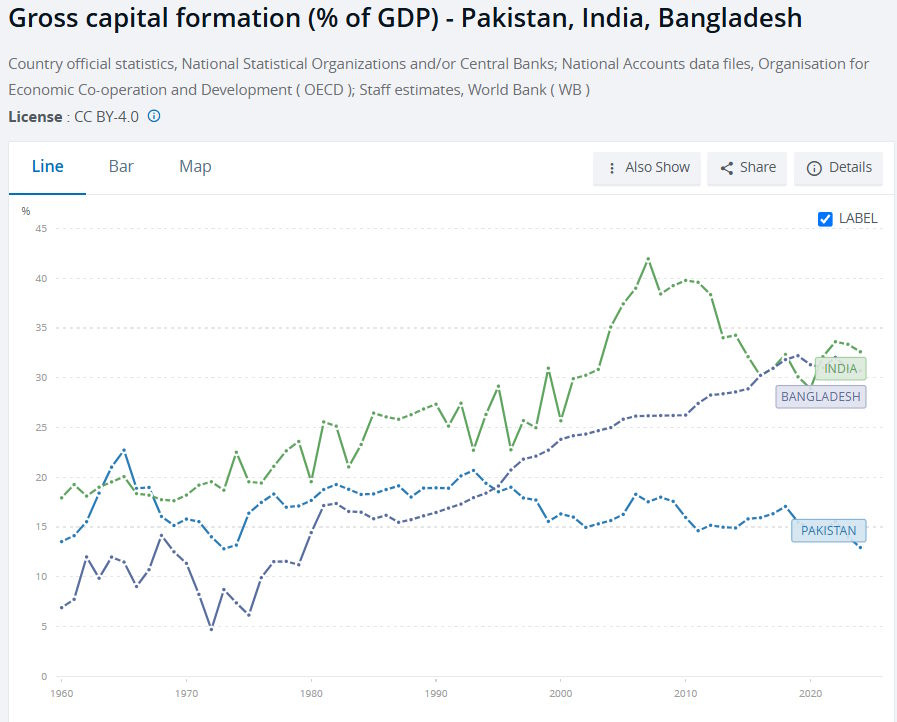

Opening rich-country markets to textile exports also helped get Bangladesh’s garment manufacturing sector off the ground, which has enabled that country to climb out of absolute poverty.

Importantly, though, these positive effects happen even when poor countries don’t see a manufacturing boom at all. Kassa and Coulibaly (2019) found that AGOA usually didn’t stimulate manufacturing in the long term, and usually just allowed African countries to sell more commodities to the U.S. But this ended up having a positive effect on growth in those countries anyway.

Right now, American policy is going in exactly the wrong direction. AGOA was allowed to expire this year, which will definitely hurt poor countries in Africa — including four of the Big 5. Meanwhile, Donald Trump is slapping tariffs on Africa, and has threatened tariffs on Pakistan as well. This might satisfy MAGA machismo in the short term, but in the long term it’s going to lead to a lot more African migrants trying to get into the U.S. — not exactly the kind of outcome Trump would probably like. Meanwhile, opening American markets to Pakistani goods might prompt that country’s government to try to emulate its South Asian neighbors, building industries like garments, textiles, and so on, and investing more of its GDP for the future.

So opening American markets to products from the Big 5 is a win for everyone involved.

Another pretty obvious idea is foreign aid. There’s a huge debate on whether aid actually raises growth — whether it actually “teaches a man to fish”, as the saying goes. The best literature review here that I know of is Dreher, Lang, and Reinsberg (2024). They find that aid does increase growth a bit, especially in very poor countries (like the Big 5). But the bigger effect is on poverty, which aid seems to reduce by a decently significant amount. That decrease in poverty comes with big improvements in health and welfare — things that tend to drive fertility down faster. That can reduce overpopulation in resource-dependent poor countries like the DRC, which means more natural resource rents to go around.

MAGA types might balk, however, at Dreher et al.’s finding that aid increases emigration pressure. When you give poor people money, or simply relieve their economic stress, one of the things they use that money for is to move out of their country to somewhere with better opportunities — like Europe or the U.S. MAGA is fundamentally an anti-immigration movement, so it might be a bridge too far to ask American conservatives to support aid, despite the long-term effect on population reduction. China, however, might still be persuaded to dish out more aid, especially given the geopolitical benefits it might reap from doing so.

One policy that’s probably not a good idea is to give money to the governments of the Big 5. Back in 2021, I wrote about how Pakistan has basically learned how to get repeated giveaways from the IMF (and now China), in the form of “loans” that get predictably and repeatedly “forgiven”:

This infinite lifeline of free money acts a bit like oil does for a petrostate, allowing Pakistan to exist at a subsistence level without investing its savings or building up its industry much. While India and Bangladesh invest to grow their economies for the future, Pakistan fritters its money away on hanging on to an impoverished status quo:

Therefore, aid to the Big 5 should go directly to the people of those countries — to building schools and hospitals, training teachers and doctors, and even just giving poor people cash. The governments of these dysfunctional giant nations should not be given sources of free cash.

But one thing the world can do for the Big 5 is to try to provide them with military stability. While Pakistan and Tanzania are largely stable (despite Pakistan’s frequent coups), the DRC, Nigeria, and Ethiopia are plagued by near-continuous warfare between fragmented ethnic groups, with the occasional religious movement thrown in. Increasing UN peacekeepers, other international peacekeepers, and diplomatic mediation efforts for those three countries would probably yield big dividends, allowing their fragile governments to focus a little more on economic and social development and a little less on war. Research generally shows that peacekeeping operations reduce conflict in poor countries, though they’re not a panacea.

The harsh reality is that nothing rich countries do is likely to turn countries like the DRC and Nigeria into countries like China and India. But there’s a lot we can do — for very low cost to ourselves — in order to push these countries toward a more livable, sustainable future. And in doing so, we can hopefully avert a world where most people live in a failed state.

At 2025 purchasing power parities. I converted from the numbers in that paper.

I’m genuinely worried about Nigeria. The country is trapped in a cycle of bad policy because its political economy is so distorted and painful to reform.

Let’s start with agriculture. Nigeria has five times more arable land than Vietnam, yet Vietnam produces five times more rice (and Nigerians love rice!). The problem isn’t the soil or the climate. It’s the institutional rot surrounding land tenure, which makes farming insecure, unproductive and unrewarding.

Land rights in Nigeria are among the weakest in the developing world. Most land is still governed by customary law, where chiefs or family heads are custodians rather than individuals with formal deeds. The result is a tangled mix of statutory(normal common law), customary (chief law), and (in the North) Islamic law, often overlapping and contradicting one another. Ownership disputes can take years to resolve. Without clear titles, farmers can’t use land as collateral to obtain credit or invest in machinery, irrigation, or fertilizers.

Even worse... The dysfunction varies by region:

Yorubaland (Southwest): Land is family-owned (“Omo Onile,” or son of the soil). Any sale or lease requires the consent of multiple relatives, slowing transactions and breeding extortion. In Lagos, Omo Onile groups often sell the same parcel multiple times.

https://www.scirp.org/journal/paperinformation?paperid=125968#:~:text=The%20word%20“Omo-Onile”,dynamics%20and%20informal%20land%20governance

Igboland (Southeast): Land belongs to the extended family. Individuals have only rights of use, not ownership. That discourages long-term investment and prevents land from being used as collateral.

Edoland (South-South): Chiefs and palace authorities hold land “in trust” for the community but increasingly lease it out for personal gain, creating corruption and displacement.

Northern Nigeria: Land allocation under customary and Islamic law is informal and based on the goodwill of emirs. Farmers can cultivate plots for generations without formal titles, leaving them vulnerable and limiting access to bank credit.

Middle Belt: The Jukun areas are especially volatile because overlapping ethnic claims and weak documentation invite manipulation by local politicians, who can “reallocate” land to their supporters under the guise of resettlement or development.

You see how fragmented this is? Unlike East Asia which had issues with massive tenant farmers serving a few landlords, where all you had to do was land reform. Nigeria's land problem is fragmented authority, weak institutions, and overlapping legal systems. That uncertainty keeps agriculture stagnant and deters modernization.

No one can fix Nigeria's land tenure because of the political economy (current actors benefitting from the status quo).

1. Chiefs, local officials, and political elites make money from the opacity through land sales and etc. Formalizing titles would reduce their leverage.

2. There's a Federal State Power struggle. Post 1978, land is in control of state governors, giving them discretionary power to allocate land. It's a political goldmine that governors would never give away.

3. Some rural communities trust their chiefs more than the state. So a politician would be more favored by defending local customs to secure votes instead of pushing for formal titling.

As the book How Asia Works notes, successful industrializers began by fixing agriculture. Nigeria isn’t even there yet. I write a lot about Nigerian history here if anyone cares.

https://yawboadu.substack.com/p/the-remastered-economic-and-geopolitical?r=garki&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&triedRedirect=true

This is very sensible and I do know quite a bit about it. To the person who decried “white saviour complex”, I would respond that this is no more than the obligation on rich people to help those far poorer than themselves. What has that to do with skin colour? I worked at the World Bank as a senior economist in the 1970s. The big story is how unexpectedly well developing countries have done since then. My main focus was on India. I even wrote a book, published in 1982, arguing for radical trade liberalisation. Since that happened, as Noah writes, India has been transformed. I do not need to say anything about China. Of course, many Americans seem to hate the fact that these countries have become richer and so far more powerful. Tough! And can Pakistan follow? Of course, it can.