Bad and good arguments for industrial policy

Has China invented a better way to run an advanced economy?

Throughout the 2010s, a number of people argued that China had discovered a better way to run an economy. Obviously the country was still relatively poor at the time, and it’s easier to grow quickly from a lower base. But what was remarkable about China’s growth was that it was so consistent — China never officially experienced a recession in the 2000s or 2010s, despite the global financial crisis of 2008 and the Chinese stock market crash of 2015. It seemed to have found the secret sauce of macroeconomics.

That secret sauce came with a cost. China avoided recessions by having its state-controlled banks lend lots and lots and lots of money to the real estate industry. That ended up reducing productivity growth, by channeling capital into less productive uses. It also exacerbated a gigantic real estate bubble that has now popped, leading to another growth slowdown that’s almost certainly worse than China’s official statistics say, and which has left large parts of the populace pessimistic and unhappy.

So I’d say we still don’t know whether China managed to invent a better form of macroeconomic stabilization policy. At this point I’m kind of leaning toward “No.”

But anyway, despite the slowdown, some people are now again claiming that China has found a better way to run an advanced economy. The argument I’m seeing is that China’s industrial policy — basically, a huge program of subsidies to various advanced manufacturing industries — is simultaneously creating a consumer paradise for Chinese people and pushing the frontiers of innovation. The rise of China as a fierce international competitor in industries like electric vehicles, solar power, batteries, machine tools, and trailing-edge computer chips has seemed to lend credence to this argument.

Now in recent years, I’ve become a strong advocate for industrial policy in the U.S. and other advanced nations. But my primary justification has been national security rather than national wealth. This is a very important distinction. Even if promoting industries like semiconductors and drones makes your country a little bit poorer, that could easily be a cost worth paying in order to maintain a strong defense-industrial base and an edge in military technology. Any efficiency loss from industrial policy can therefore be viewed as a cost of national security, which is one of the most important public goods that governments provide.

But the boosters of China’s current industrial policy push are making a stronger claim. They’re claiming that China’s subsidy programs are a new and better way to raise a nation’s standard of living.

For example, Han Feizi, a pseudonymous1 author or group of authors writing at Asia Times, has a much-discussed article in which they argue that China’s subsidy-driven industrial policy represents an economic system that’s superior to the pursuit of profit maximization and higher corporate valuations that defines Western business. Here are some excerpts:

248 years after the publication of Adam Smith’s “The Wealth of Nations” and the West has lost the economic plot…To celebrate Tesla’s US$788 billion market cap in comparison to BYD’s $93 billion is to confuse incentives with outcomes. Both companies receive generous tax breaks and other government goodies. That Tesla is far more profitable than BYD while EVs have far less market penetration in the US is evidence of policy failure, not Elon Musk’s brilliance. Tesla pocketed the incentives while BYD (and competitors) delivered outcomes…

[T]he fact that China’s photovoltaic companies are slaughtering each other by flooding the world with cheap solar panels is prima facie evidence of stunning policy success and value creation.

What we want from the butcher, the brewer and the baker are beef, beer and bread, not for them to be fabulously wealthy shop owners…The much-heralded multi-trillion dollar valuations of a handful of American companies (Microsoft, Apple, Nvidia, Alphabet, Amazon and Meta)…are symptoms of serious economic distortion…China stomped on its tech monopolies and now manages to deliver similar if not superior products and services – able to make inroads into international markets (e.g. TikTok, Shein, Temu, Huawei, Xiaomi) – at always much lower prices.

The Western business press, confusing incentives with outcomes, lazily relies on stock markets to determine value creation. The market capitalization of a company is an important but entirely inadequate measure of economic value.

This is, of course, a piece of nationalistic boosterism from an author who consistently churns out nationalistic boosterism. It’s not hard to find holes in the view of China that “Han Feizi” presents. For example, if you actually think American businesspeople are running away with all the money in the economy while Chinese businesspeople are living modest lives for the good of the nation, you should remember that China has the exact same share of wealth owned by the top 10% as the U.S., and a higher income Gini coefficient. Furthermore, despite the fall in labor’s share of national income in the U.S., it’s still higher than in China:

And despite Han Feizi’s protests to the contrary, China is no consumer paradise for the vast majority of its people — consumption is only 39% of China’s GDP, compared to 70% of America’s. A bit of China’s very high investment levels come at the expense of corporate profits, as Han Feizi discusses, but most of it comes at the expense of regular Chinese people’s consumption.

But despite these important omissions, Han Feizi does make four interesting arguments about the positive effects of China-style industrial subsidies. Roughly, these claims are:

Subsidizing production improves consumer welfare by creating abundance

Subsidizing market entry improves consumer welfare by increasing competition

Industrial subsidies correct various negative externalities

Industrial subsidies accelerate innovation

The first of these ideas is just wrong, but it’s useful to explain why it’s wrong. The third one is true for a relatively narrow range of goods. Argument #2 is a little bit interesting, and argument #4 is very interesting. So let’s go through these ideas.

Subsidizing production usually doesn’t make consumers better off

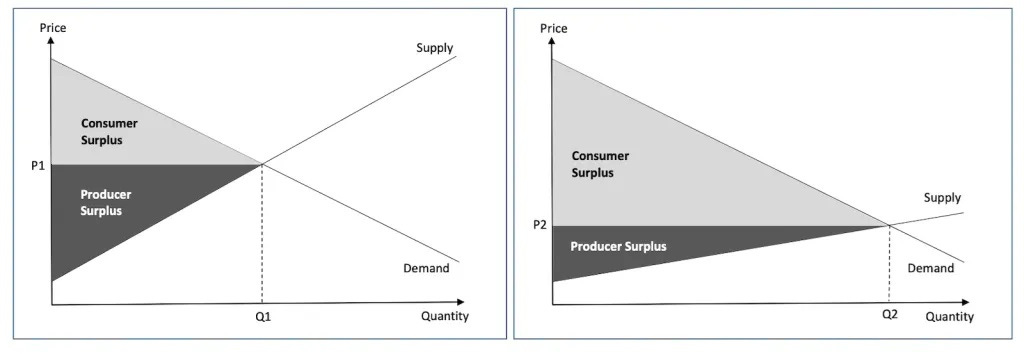

Han Feizi actually draws a supply-and-demand diagram in their article, in order to argue that subsidies for consumer products like EVs increase consumer surplus. That’s cool! Their graph shows a supply curve shifting to the right and flattening out in response to subsidies, so that consumer surplus increases by a lot:

Regular readers of this blog know that I love supply-and-demand graphs. But this is a case where using this type of graph will lead us astray. The reason is that a supply-and-demand graph like this describes only one market — only one little piece of the economy. In econ jargon, it’s a graph of “partial equilibrium”. But when we’re thinking about policies for the economy as a whole, we can’t only think about one market — we have to think about how they all affect each other. That’s called “general equilibrium”.

Let’s take Han Feizi’s example of electric vehicles. China subsidizes EVs by quite a lot. That definitely increases the supply of EVs, which increases consumer surplus — just like in Han Feizi’s graph.

But what you don’t see on the graph is that the increase in EV supply requires resource inputs — labor, energy, land for factories, and so on. If you subsidize EVs, more workers will work on building EVs — but that means fewer workers for other tasks. More workers in BYD factories might mean fewer nurses for hospitals, or authors to write interesting books, or software engineers to code new apps, etc. Even as the EV supply curve shifts to the right, the supply curves in the industries that compete with EVs for resources will shift to the left, reducing consumer surplus in those industries. And that reduction in consumer surplus in non-subsidized industries can easily outweigh the increase in the subsidized industries, because the subsidies are basically telling consumers “No, don’t buy the thing you originally wanted to buy, buy this other thing instead.”

Simply pumping up supply in one industry, or 50 industries, isn’t a free lunch. Telling an economy “No, don’t produce that stuff, produce this other stuff instead” won’t automatically increase consumer surplus. It’s basically a form of central planning, and central planning doesn’t tend to increase consumer welfare, because it tells the economy to produce what the planners want instead of what the consumers want.

Now, there is one important situation where subsidies do make consumers better off. If an economy is in the middle of a recession or depression, there will be lots of idle resources lying around — unemployed workers, shuttered factories, and so on. In that case, industrial policy can act as a Keynesian fiscal stimulus, forcing idle resources back to work. China may have idle resources right now due to its big real estate crash, which may have driven up unemployment. Although Han Feizi will be loath to admit this (because it would counter the nationalistic image of China’s economy as invincible), China’s vast industrial subsidies might be helping keep the economy afloat. The author notes this briefly in passing when they write that industrial subsidies provide “jobs for swarms of new STEM graduates”. But they don’t linger on this point, since it would require admitting that the swarms of STEM graduates were having trouble getting jobs on their own.

Anyway, Han Feizi also completely glosses over the question of how industrial subsidies are financed. In general, a government can pay for corporate subsidies one of three ways:

Raise taxes

Increase government deficits

Get private actors like banks to pay for the subsidies, e.g. by forcing banks to offer loans at far below market rates

Each of these methods tends to create economic distortions. Taxes create deadweight losses, government deficits weaken a government’s fiscal position and create macroeconomic risks down the line, and forcing banks to subsidize unprofitable manufacturers weakens the financial system.

Subsidizing entry might decrease monopoly rents, but it’s complicated

Han Feizi also argues that subsidizing new companies to enter the market reduces monopoly power, thus benefitting consumers. They try to represent this by flattening the supply curve on their graph. That’s actually not the right way to show this change on a graph, but let’s put that aside and just discuss the basic idea of entry subsidies.

Monopoly power hurts an economy in various ways. It reduces supply in the economy, because monopolists restrict output in order to jack up the price of goods and services. Reduced supply means lower growth and lower productivity. Companies with market power also tend to be monopsonies in the labor market, which drives down wages. Basically, market power is bad, and it’s important to find a way to curb it.

The normal way that economies try to curb market power is by competition policy — antitrust lawsuits, merger restrictions, and so on. But entry subsidies are a perfectly valid policy too. The idea is that powerful companies maintain their dominance because it’s difficult for upstarts to enter the market and challenge them. So if you have the government subsidize a bunch of new companies to enter the market, it puts pressure on the powerful companies to lower their prices, thus benefitting the consumer and increasing supply.

There are a bunch of theoretical econ papers about this, but my favorite is “Entry vs. Rents” by David Baqaee and Emmanuel Farhi (2020). I like this paper because the model is very flexible, allowing for lots of different moving parts in the economy and lots of ways that policy can affect competition. And despite the complex model, the authors manage to extract some pretty simple, robust conclusions. They write:

We investigate markup regulation and entry subsidization, which can loosely be thought of as capturing respectively competition and industrial policy. These two types of interventions neatly illustrate two very different ways in which forward and backward linkages can matter…For entry subsidies, the biggest gains…come from subsidizing those industries which are upstream in complex supply chains, namely primary industries like forestry, oil, and mining, whereas subsidizing entry into relatively downstream industries…is actually harmful[.]

This is a nuanced conclusion. It implies that China’s subsidies of computer chips, batteries, solar, steel, and other upstream goods are good for competition, but that subsidies of downstream products like EVs are not so great.

Of course, one theoretical paper isn’t the final word on the topic. It’s just a much more complicated question than Han Feizi or other cheerleaders of Chinese policy want to make it out to be. But there is definitely the nugget of an interesting, potentially useful policy in there.

Externalities exist, but subsidies often aren’t the way to fix them

Han Feizi also argues that the economy is full of externalities that industrial subsidies fix:

The more significant outcomes of industrial policy are externalities. And it is all about the externalities.

To name just a few, switching to EVs weens China from oil imports, lowers particulates and CO2 emissions, provides jobs for swarms of new STEM graduates and creates ultra-competitive companies to compete in international markets.

Externalities from the stunning collapse of solar panel prices may be even more transformative. Previously uneconomic engineering solutions may become possible from mass desalinization to synthetic fertilizer, plastics and jet fuel to indoor urban agriculture. China could significantly lower the cost of energy for the Global South with massive geopolitical implications.

Most of the things being named here aren’t actually externalities. For example, providing jobs for STEM graduates isn’t an externality at all, because there’s no obvious spillover benefit to anyone other than the people who get the jobs. Yes, there are probably some externalities in the labor market — disappointed over-educated elites might cause social unrest, for example. But these effects are very unclear, and there’s no obvious reason to think that subsidizing various types of jobs will improve things for society at large.

Similarly, benefits for downstream industries from subsidizing upstream industries are not externalities — they’re just market distortions. Yes, if you make energy cheaper, you will also get cheaper fertilizer and plastics. But that cheapness happens through the regular market price system, not through some sort of unpriced spillover benefit. And as I explained in an earlier section, this all comes at a cost — if you use subsidies to get cheaper plastic and fertilizer, you have to divert resources from elsewhere, which raises costs for other goods. The same is true of creating competitive companies and exporting cheap energy. It’s just not clear what the externality is supposed to be here.

Han Feizi does cite two cases of plausible externalities. The first is reducing China’s oil dependence. This increases China’s national security; national security is a public good, which is a positive externality. But if this increased energy security makes China’s leaders feel that it’s safe to launch a destructive war in Asia, then the positive externality could quickly turn into a negative one.

Of course the most plausible case of an externality is the environmental one. By subsidizing solar panels, batteries, and other technologies to replace fossil fuels, Chinese industrial subsidies are doing a huge amount of good — not only for the people of China, but for the world. Those green technology subsidies are the clearest, most powerful example of China’s industrial policy producing beneficial results.

But it makes no sense to just claim that producing any sort of industrial good creates a positive externality. And even when externalities do exist, “produce more stuff” generally isn’t the way to fix them. In fact, since many kinds of industrial production create water and air pollution, and since China still burns a lot of coal to power its industries, much of the country’s industrial policy push could even create negative externalities.

Industrial policy might accelerate productivity growth

So while some of Han Feizi’s core arguments are interesting, they have severe limitations and qualifications. But the author does hint at a more interesting and potentially revolutionary justification for China-style industrial subsidies — they might accelerate innovation.

In How Asia Works, Joe Studwell argues that developing countries can raise their productivity levels through something called “export discipline”. Basically, export discipline is two things:

Subsidizing companies that export their products

Withdrawing subsidies and culling unsuccessful companies after an initial period

Step 1 is supposed to push companies to compete in more challenging overseas markets, absorb foreign technology, and develop new products more suited to global tastes. Step 2 is supposed to minimize the costs of the policy and reallocate resources from unproductive companies to productive ones. Together, these steps are supposed to function as a sort of research project — a country discovering what kinds of goods it can successfully specialize in, how to sell them, and which of its people are best suited to selling them.

But this raises the question: What if you used this approach to subsidize production in general, instead of just exports? Suppose your country doesn’t yet have a great car industry. So you pay a bunch of companies to try their hand at making cars. Some succeed, some fail. You withdraw the subsidies and make sure that the failed carmakers fail. At the end of this process, you might have some successful carmakers where you didn’t have any before! And those carmakers, almost by definition, will have technologies that your country never had before.

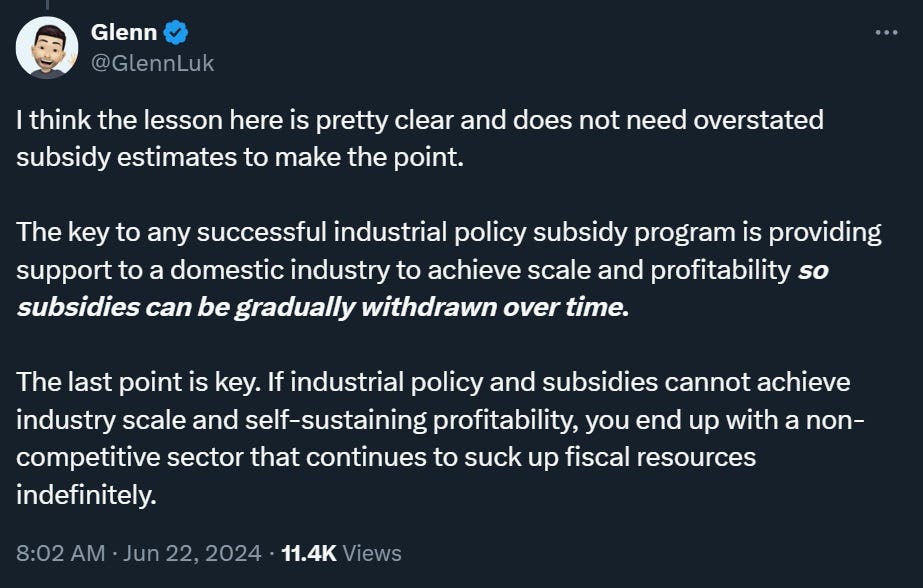

Although Han Feizi only alludes to this idea, others have endorsed it explicitly and used it to argue that China’s economic model is superior:

(Note: In the comments, Glenn specifies that he thinks this model is better for China, but not necessarily for other countries.)

In fact, it’s possible to write down an economic model where this procedure is highly effective for increasing a country’s productivity levels. I guess that doesn’t say much, since it’s possible for a skilled theorist to model practically any economic result they want. Obviously, this sort of approach to raising national productivity levels needs to be tested empirically and not just theorized about. And the only real way to test a policy is to try it and see what happens.

China has had a big problem with slowing productivity in recent years:

Given this situation, it makes sense for China to try some out-of-the-box thinking. Industrial subsidies aren’t an orthodox way of raising national productivity, but they might work. If we don’t try out new economic models, we’ll never find anything better than what we have today.

But that being said, I think it’s good to be circumspect about trumpeting those new models and declaring victory before we’ve had a chance to see their effects fully play out. Countries occasionally do invent new and improved ways to run an economy. But the number of people who have gotten egg on their face for prematurely bragging about approaches that ended up coming with significant costs is long indeed.

“Han Feizi” is actually the name of an old philosophy book that summarized and advocated for “legalism”, a highly interventionist and somewhat authoritarian philosophy of government.

"... others have endorsed it explicitly and used it to argue that China’s economic model is superior"

Noah, this is actually not my position on this. My position is that China's economic model is fit to China and the unique set of conditions that it operates on at this point in history.

Broadly speaking, I do not believe you can wholesale remove a system and set of policies from their underlying conditions and apply it to another situation with a whole different set of underlying conditions.

Specifically with respect to industrial policy in the United States, I very much go back and forth on whether trying to implement China-style industrial policy in the United States would work (or even backfire) because of major differences in those underlying conditions.

What I do think is important is gaining an accurate understanding of how things work in China (including industrial policy) because there are direct impacts to the U.S. and global economy. Indeed, the optimal response may ultimately have to be doing something completely different because what works under one set of conditions (China) will often not work under a completely different set of ones (e.g. in the U.S.).

Edit - my thoughts in response: https://x.com/glennluk/status/1814356615476236792?s=61

I like this a lot. I’ve always opposed your support for industrial policy because I assumed it was rooted in arguments for economic vitality. But I would agree; national security is unambiguously a benefit of effectively targeted industrial policy.

I would also say the concern here is that virtually any rent seeking industry is going to make the national security argument because they know it resonates. And I think the US has really fallen victim to that, as its proponents in DC have also tried to make things about national security which are not about national security.

This argument is also interesting because it is disjointed from what appears to be the primary reason industrial policy enjoys whatever popular support it enjoys: 1. Bringing low skilled jobs back to the US (I would argue that industrial policy to achieve this is like putting a band aid on a gunshot wound; it’s a superficial solution that doesn’t address the underlying problem and 2. As a means of countering globalization.