The case of the angry history postdoc

Elite overproduction spotted in the wild.

I wasn’t planning to write a post about today’s Twitter contretemps…but, a friend asked me to. And I guess it is kind of an interesting window into social and economic trends among the American elite. So here goes.

Today’s Twitter contretemps involved one David Austin Walsh, a history postdoc at Yale. (For those who don’t know, a postdoc position is a sort of low-paid purgatory where people with PhDs get sent to keep doing research when they can’t immediately get jobs as professors.) Walsh is the author of a recently released book, Taking America Back: The Conservative Movement and the Far Right, but he’s best known as a vocal and highly opinionated commentator on Twitter. When my podcast co-host Brad DeLong declared in 2019 that it was time for neoliberals like himself to “pass the baton” to their colleagues further to the left, it was a tweet thread by Walsh that he cited. In recent years, Walsh has spent much of his time attacking Joe Biden from the left; these attacks have become more strident since the start of the Gaza war.

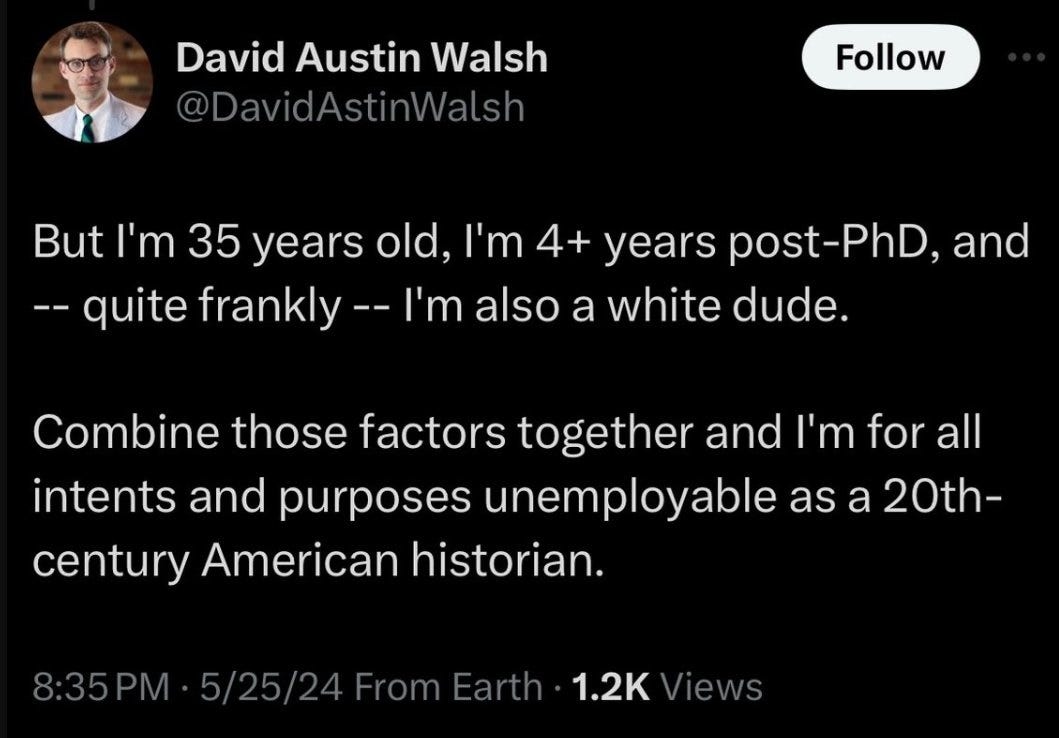

But that is not what got Twitter — or X, as it’s now officially known — in a tizzy today. Instead, it was Walsh’s declaration that his failure to get a tenure-track academic job is due, at least in part, to the fact that he is a White man:

When a (nonwhite, female) history professor disputed this assertion, he accused her of “punching down” on him from her position of power.

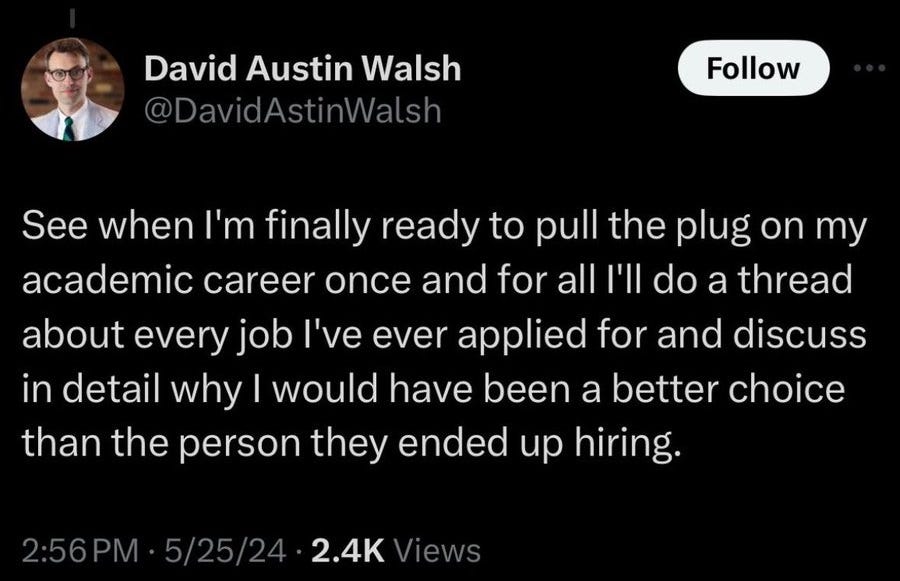

This angered absolutely everyone on Twitter, from progressives who decried Walsh as just one more mediocre White man who assumes he’s more qualified than women and people of color, to conservatives who derided Walsh as someone who brought this upon himself by supporting the rise of an unfair DEI regime. The only thing the various sides could agree on was that they all despised Walsh. A day-long battle royale ensued. Walsh issued a stumbling apology, but it’s pretty clear that he does in fact believe that he was more qualified than the people who got the jobs he applied for:

I do think the issue of discrimination in academic hiring is slightly interesting, and I’ll get to that in a bit. But what interests me more about the Walsh Affair is how it seems to provide an example of elite overproduction.

About a year and a half ago, I wrote a post laying out a hypothesis about why there has been so much discontent among the American intellectual elite over the past decade:

The basic idea1 is that lots of careers for educated elites — humanities and social science academia, law, journalism, and so on — started becoming a lot scarcer right around the same time. This inevitably led to a bunch of frustrated strivers with big expectations and no way to fulfill them. And that mismatch between expectation and opportunity, I hypothesize, fueled some of the unrest of the 2010s.

David Austin Walsh appears to be a perfect example of the social process I was describing. He’s had an extremely elite education — he went to the University of Minnesota and did his PhD at Princeton. And he clearly thinks very highly of his own abilities, judging by his plan to write a thread explaining why he was more qualified than every person that ended up getting hired instead of him. One time when he took a practice LSAT and didn’t do well, he blamed his performance on the test questions being “right-wing”.

That kind of lofty self-regard very easily leads to high expectations for career achievement. And it’s clear that Walsh expected not only to get a tenure-track academic job, but a job in his particular research field — 20th-century U.S. history. There aren’t many such jobs in existence, but that was what Walsh had set his sights on. And it’s his failure to get that specific job, in that specific field, that made him get frustrated and lash out in the thread that made everyone angry.

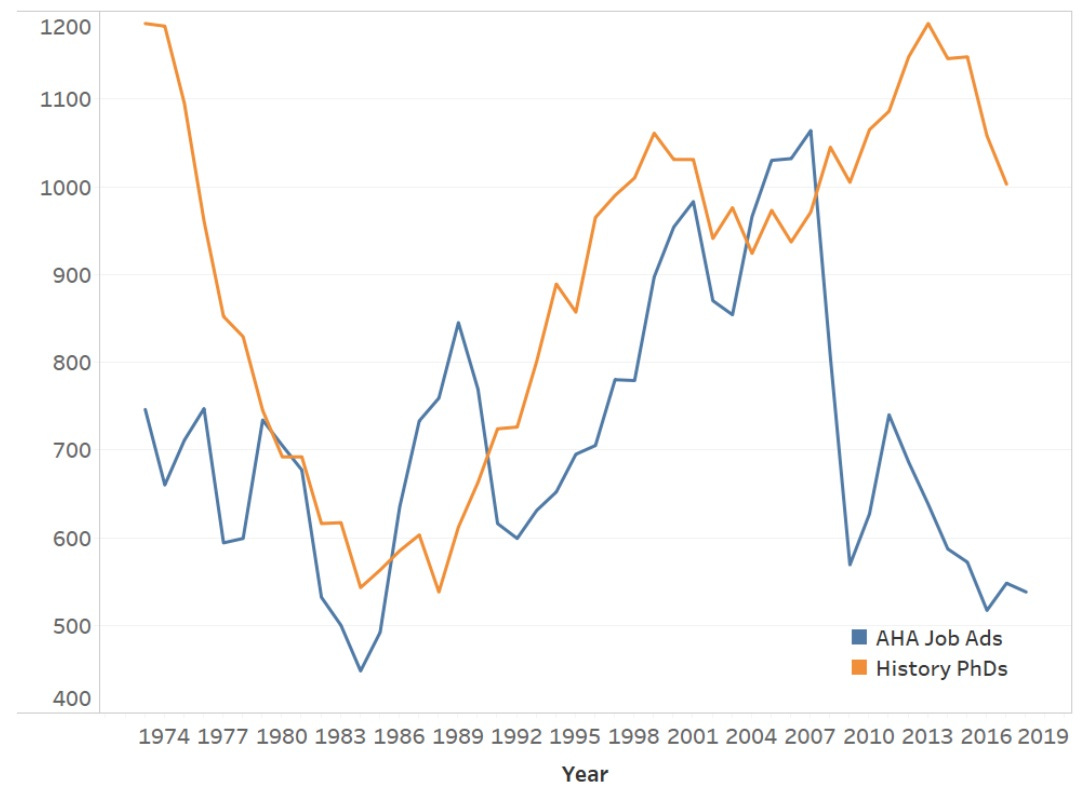

It was always very likely that someone was going to get frustrated for exactly this reason. History professorships are an extremely scarce commodity these days. Plenty of people are still getting PhDs in history, but ads for history professor jobs collapsed in the Great Recession and never recovered:

And most of the collapse has been concentrated in jobs for assistant professors — the type of entry-level professor job that Walsh was trying to get.

Why is no one hiring historians? There are four basic reasons. The first and most important — which almost no one ever talks about, because it’s supposed to be so obvious — is that the U.S. university system is largely done expanding. The 20th century saw a massive build-out of universities, which required hiring a massive number of tenure-track professors. Then it stopped. And because tenure is for life, the departments at the existing universities are clogged with a ton of old profs who will never leave until they age out. New hires must therefore slow to a trickle, since as long as the number of profs is roughly constant, they can only be hired to replace people who retire or die.

The second reason is the funding crunch that hit universities in the Great Recession of 2008-9. That recession put a lot of pressure on state budgets, and spending on state universities was one thing they could cut. So cut they did. And when the economy recovered, some states didn’t restore pre-recession funding levels. Universities made up the lost revenue by hiking tuition, which made everyone mad.

Those tuition hikes were poorly timed, because of the third reason no one is hiring historians these days: College enrollment itself is falling. This is partly because the number of young people in America has mostly stopped growing. And it’s partly because the financial benefit of higher education — the college wage premium — has been shrinking slowly since the turn of the century.

That falling premium is probably a good thing for the country — the likeliest reason is that we sent so many Americans to college that we created a glut of educated workers. But when a country has fewer kids facing higher prices for a less valuable education, you’re probably going to see fewer people go to college. And that means less demand for professors in general.

But there’s a fourth reason that the demand for historians has fallen: College kids are increasingly avoiding the history major. History degrees peaked as a share of BAs right before the Great Recession, and their share has absolutely collapsed since then:

In general, students have been flooding out of humanities and non-econ social sciences, and flooding into fields like computer science that they feel offer them better employment prospects. History has been one of the hardest hit.

Historians may see research as their primary job, but universities’ demand for history professors strongly depends on the number of undergrads majoring in history. If that number is falling off a cliff, you’re just not going to see many tenure-track jobs for historians. Meanwhile, state budget cuts and now falling tuition are promoting the rise of adjuncts and lecturers instead of tenure-track faculty.

So while half a century ago, tenure-track history jobs were relatively plentiful, today they are incredibly scarce — trying to become a tenured history prof isn’t quite like trying to become a movie star or a drug kingpin, but it has certainly moved in that direction.

When jobs in a field are scarce, it can exacerbate fights based on identity and representation. When there’s a glut of applicants all vying for one job, the margin between victory and defeat tends to be very narrow. That gives rise to a natural fear that the person who gets picked had some unfair edge. If a White person is picked, nonwhite people may suspect racism; if a person of color is picked, White people may suspect the influence of DEI. The more competitive the position, the greater the chance that even a small unfair edge will tip the balance.

This fits with my general theory of how Americans think about racial and gender discrimination. On polls about college admissions, Americans strongly support “affirmative action”, and strongly oppose considering race in admissions. But those are the same exact thing! It could be that American poll respondents just don’t understand the questions they’re responding to. But I suspect it’s something else. I think Americans like the idea of unofficial, tacit discrimination in favor of underrepresented groups, but also strongly value the idea of individual fairness, and so dislike official, rule-based discrimination.

There is a natural tension between these two goals. When times are good — when a preferential boost for underrepresented groups will still leave overrepresented groups doing fine — it’s possible, even easy, to ignore this tension. You can tell yourself that even if affirmative action biases admissions or hiring etc., the total pie is growing, so no group is actually getting hurt in the aggregate. Growth overwhelms concerns about distribution. But when times are bad, and the game becomes zero-sum or even negative-sum, it becomes impossible to sustain this happy mental duality. And so the fights over racial and gender preferences flare up again.

So it’s utterly unsurprising to me to see a fight over race and gender in the history field. Like many humanities and non-econ social science fields, academic history is shrinking, driven almost entirely by structural factors that don’t seem likely to change soon. The fights over the scraps of what’s left will inevitably be bitter.

The larger question, in my mind, is what effect this has on our wider society. The theory of elite overproduction says, basically, that the educated elites whose career expectations can’t be satisfied will respond by getting mad at wider society and fomenting unrest. Certainly, David Austin Walsh’s contentious career as a strident social media shouter fits that prediction to a T. We are just coming out of a decade in which strident social media shouters held disproportionate power over our national discourse and sociopolitical culture. That was, frankly speaking, not great for America.

So how do we fight elite overproduction? The obvious way is to just provide more careers for educated elites, but that can get extremely costly to society as a whole. Folks like Walsh have very narrow, specific expectations for their careers, and satisfying all of those would require shunting vast numbers of our most talented individuals into what are essentially make-work jobs. We can’t afford to pay everyone to be a tenured professor in the humanities or social science field of their choice.

Instead, I think that the problem calls for a shift in expectations. I think the Great Recession and Covid did help here, by disabusing lots of people of the idea that their life would be a glide path to prosperity, fame, and respect. So there has been somewhat of a reset there. On top of that, we should probably produce fewer PhDs in fields like history where academic jobs are scarce and private-sector careers are non-obvious.

(And of course, American parents should probably stop telling their kids that they’re the Smartest Kid In The World and that they’re destined for greatness, etc. etc. But I highly doubt that American parents will ever stop telling their kids this.)

But in addition to all that, I think academic advisors and other influential figures should work to make educated people’s expectations more vague. “I’m going to be a tenured professor in the field of 20th-century American history at a good university” is a hyper-specific expectation that’s very hard to meet. “I’m going to have a decent-paying job doing something intellectually interesting, while also perhaps writing a book on the side” is a very vague expectation that is eminently achievable for almost all American PhD holders. American strivers need to learn to go where the winds of life take them. Take it from me — it’s more fun that way.

Note: I stole the name of this idea from the historian Peter Turchin, but I modified it a bit from his original version. Turchin tends to focus on different sets of elites than I do — for example, politicians seeking elected office. I don’t think Turchin is wrong, I just think the theory applies equally well to the humanities-and-social-science-educated intelligentsia.

There was another change that led to a drop in academic hiring: Starting in 1994, the ADEA no longer allowed universities to have mandatory retirement ages of 70. Professors hired at 30 with the expectation that they would be forced to retire at 65 or 70 can now stick around for as long as they are able, often staying through their 70s and sometimes into their 80s. Less turnover means fewer vacancies to fill.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3737001/#R1

As someone in academia, I see exactly what you are seeing. Massive overproduction of Ph.Ds leading to applicant pools in the hundreds for every humanities position and most social science positions we advertise. I do you think you left out one important factor--a significant reason for the overproduction is that many (if not most) Ph.D-granting institutions rely on their doctoral programs both for prestige AND for low-wage instruction in these areas. This significant pool of doctoral students provides a constant supply of cheap labor, allowing the tenure-track faculty to teach many fewer courses per year compared to non-doctoral schools. This perverse incentive structure encourages even the most mediocre doctoral programs to continue to admit students that have very little chance of ever succeeding in the market.

As things currently stand, there are no real incentives for most of these doctoral programs to stop recruiting potential Ph.Ds, and there are clear incentives for them to continue to recruit new grad students to keep them teaching all those intro classes the tenured faculty want to avoid. Until academia finds a way to fix this skewed incentive structure, this problem will not go away.