No one knows how much the government can borrow

Perhaps macroeconomists should think about studying this interesting question.

One of the most important questions in macroeconomics is one that economists have curiously chosen not to study. That question is: “How much can the government safely borrow?”

In fact, no one knows the answer to this question. And because no one knows the answer to this question, no one even knows if this is a particularly important question to be asking right now. You might think that with the U.S. federal debt having surged to over 125% of GDP as a result of COVID relief spending — up from around 60% of GDP before the 2008 financial crisis, it might be time to think about borrowing constraints. And you might think that with Biden planning far more deficit spending in the coming years, it might be time to think about borrowing constraints.

But in fact, we don’t actually know if it’s time to think about borrowing constraints! It might be that we’re heading into the danger zone, or it might be that the danger zone is still so far away that we could do a CARES Act every month and not run into trouble for decades. Many people will tell you, very confidently, that they know the answer to this question, but don’t believe them. Our lack of knowledge about borrowing constraints represents a deep, profound ignorance. And that ignorance means that unless and until we actually find those limits the hard way, the policy debate over deficits in the coming years will rest completely on people’s priors, assumptions, and ideologies.

Which is not a good place for us to be.

So let’s talk a little about government borrowing constraints, and why we don’t know what they are, and why macroeconomists have been remiss in avoiding the topic.

An infinite corridor with an invisible pit

Most macroeconomic models simply assume a government borrowing constraint. They assume that in the very long run, government debt as a percent of GDP trends toward zero (or perhaps some constant value). As far as I can tell, there’s no good reason for assuming this other than the fact that it helps make the models easier to solve math-wise. So most macroeconomic models aren’t very useful for questions like this.

So instead, let’s think about what actually might happen to stop the government from borrowing money, if it just kept borrowing more and more and more. It’s an interesting thought experiment.

Who can cut off the government’s credit?

There are three basic groups of people who lend money to the U.S. government (i.e., who buy Treasury bonds):

Foreigners

U.S. private companies and citizens

The Federal Reserve

If the U.S. federal government keeps borrowing and borrowing and borrowing without limit, eventually foreigners and private companies and citizens are not going to want to buy all of those Treasuries. At that point the U.S. government can basically do one of two things:

It can offer higher interest rates, to make Treasuries more attractive, so that foreigners and U.S. private companies and citizens are willing to absorb larger amounts of debt.

It can have the Fed buy more of the Treasuries at a low interest rate.

Offering higher interest rates has its limits. Higher interest rates mean higher interest payments, which means the government will have to borrow even more to cover those interest payments. Eventually this spirals out of control and people just stop lending to the government, period. To make matters worse, higher Treasury rates push up interest rates in general, which hurts the economy.

The Fed to the rescue

So that leaves the Fed. If the Fed buys Treasuries from private companies and citizens, it can push interest rates back down — basically, banks will lend to the government at low interest rates because they know the Fed will then swoop in and take the bonds off their hands. Or, alternatively, you could just have the Fed buy newly issued Treasuries directly from the government, and cut out the middleman entirely. That would involve a legal change, but it’s possible (Japan did it in the Great Depression).

(Side note: This would be basically the same as eliminating the rule that the government has to “borrow” in order to spend money at all. The government can just spend money by magically creating dollars and putting them in your account. This is basically the same as having the Fed magically create dollars and putting them in the government’s account and then having the government spend those dollars. Anyway.)

Theoretically, the Fed can just keep doing this ad infinitum. The government wants to borrow $100 trillion per day? The Fed can just credit their account with $100 trillion per day! This is why some people say the government has no borrowing constraint.

Just little green pieces of (electronic) paper

But OK, if you keep doing this more and more and more, eventually something bad has to happen, right? Well, eventually, yeah. Every dollar that the Fed creates and gives to the government to spend is an extra dollar in the economy. If you printed a bunch of paper money and gave it out, eventually paper money would lose its value. The same is true of digital money. If you create bazillions and bazillions of dollars, eventually people will conclude that a dollar won’t be worth much.

So, if the government keeps borrowing and spending to infinity, eventually you get hyperinflation. That’s when the price of everything goes to the moon, and people’s savings get wiped out, and the economy collapses. It’s not good.

But how eventually is “eventually”? We have no idea.

For hyperinflation to happen, companies have to start raising prices really rapidly. And we don’t know when they’ll do that, because we really understand very little about how companies behave in this regard (more on that later). At some point, presumably, the companies look at government spending and go “Oh shit, the dollar is going to be worth NOTHING”, and then they just start raising their prices like crazy because they think the dollars they’re getting are about to be worth much less. But “at some point, presumably” is a polite term for “we have no idea when”.

(Side note: In fact, it’s more complicated than this, because while the government can create and destroy money, banks can too. So if the government creates a lot of dollars via spending but banks destroy it via reducing lending, then the amount of dollars floating around the economy won’t go up, and companies will be less likely to freak out and start raising prices rapidly. This happened during the Great Recession. But we don’t really know what makes banks do this, or when the process might stop. Presumably banks could reduce lending all the way to 0, but would they? And what would the economy look like then?)

So where’s the inflation, genius?

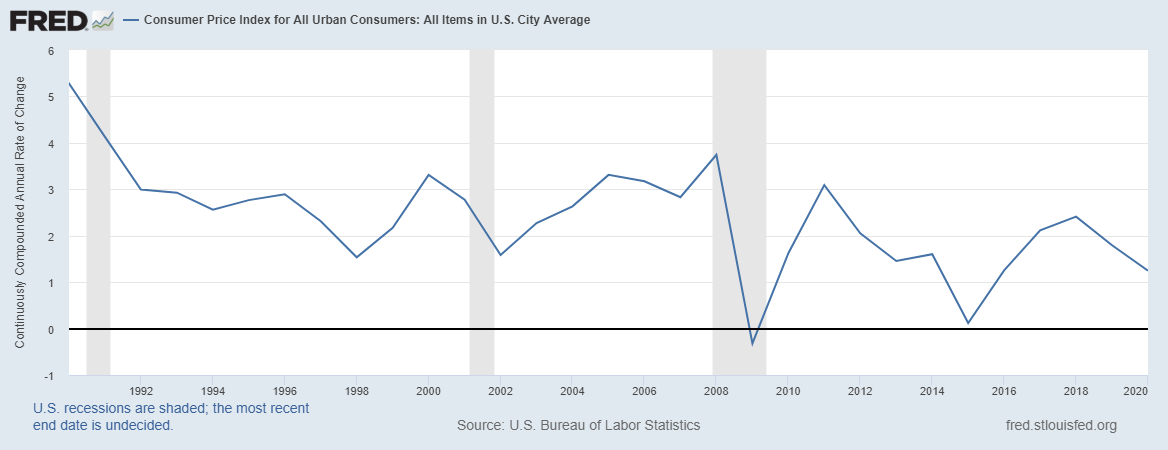

Remember that some people thought that government borrowing and spending during the Great Recession, facilitated by quantitative easing (Fed bond-buying) to keep interest rates low, was going to lead to substantial inflation. But it didn’t.

Would it have led to inflation if the government borrowing and spending had been 10x what it was? 100x? 10000000000000000000000x? Where’s the cutoff?

We don’t know. David Andolfatto, writing at the St. Louis Fed blog, lays it out:

There is presumably a limit to how much the market is willing or able to absorb in the way of Treasury securities, for a given price level (or inflation rate) and a given structure of interest rates. However, no one really knows how high the debt-to-GDP ratio can get. We can only know once we get there…There is no way of knowing beforehand just how large the national debt can get before inflation becomes a concern.

So when the government borrows more and more from the Fed and spends the money, it’s like our country is walking down an infinite corridor towards an invisible pit. We know the pit is out there somewhere in front of us, but we just have no idea how far we have to walk before we fall in.

But if we ever do fall in…whew. It’s quite a pit. Countries with hyperinflation, like Venezuela, see their economies just completely collapse. Savings are wiped out. Businesses stop investing. Store shelves become empty. People suffer. Hyperinflation is worse than a sovereign default — both effectively wipe out all debt, but the former drags on for much longer and does much worse damage.

Hyperinflation is so incredibly destructive that you’d think macroeconomists would spend a lot of time studying the phenomenon, figuring out when and why it happens. Especially because the answer to the question of hyperinflation is also the answer to the question of how much the government can borrow. An understanding of hyperinflation would give us a flashlight to shine down the infinite corridor, so we could avoid the pit.

But weirdly, macroeconomists mostly ignore hyperinflation.

Macroeconomists, please study hyperinflation

So, first of all, if you don’t know macroeconomists, realize that any time you say they’re not researching some topic enough, they will get very mad and bombard you with papers on that topic. This is certainly going to happen to me shortly after I hit the “publish” button. In macroeconomists’ minds, they are always studying every topic to its fullest extent at every moment. But if that were true, then a Google Scholar search for papers on “hyperinflation” since 2010 probably wouldn’t be dominated by papers about cryptocurrencies and biology papers about lung inflation. And a glance at the literature review section of one of the few recent papers on hyperinflation wouldn’t be dominated by papers from 1986 and earlier. More importantly, we’d probably have at least some some well-known tentative answers to the big questions:

At what point does government borrowing trigger hyperinflation, and what factors influence this threshold?

Will inflation rise slowly enough in order to see it coming and stop it?

How can government prevent hyperinflation if and when it sees hyperinflation coming?

The paucity of recent research on hyperinflation is probably due to the fact that top-journal econ research is highly concentrated in the U.S., and inflation hasn’t been a problem in America for several decades now. Remember that macroeconomists tend to always fight the last war — in 2008, right before a financial sector crash took down the U.S. economy, most macroeconomic models didn’t even include a financial sector at all.

The one famous paper

What research there has been usually focuses on the question of how to end a hyperinflation once it begins. The seminal paper here is Thomas Sargent’s “The Ends of Four Big Inflations.” Sargent pins the start of the hyperinflations on regime changes — basically, new governments coming in who took a completely different approach to policy — but admits that this would be hard to test empirically. The episodes ended, he argues, when governments cut deficits and independent central banks stopped agreeing to finance government spending.

Sargent’s historical narrative is useful because it shows that all of the episodes involved government banks financing government deficits. That’s useful, because it fits with the idea that hyperinflation represents the true government borrowing constraint. But there are several reasons why Sargent’s paper, while important, doesn’t help that much with the three big questions I listed above.

First, as the title indicates, most of his analysis focuses on the ends of the hyperinflations, not their beginnings; but while climbing out of the pit is undeniably important, it would be far better to never fall in in the first place. Second, Sargent doesn’t really have the data to do any sort of forecasting exercise or give more than a broad overview of some trends. Third, he doesn’t really compare these countries to other countries that had similar characteristics but didn’t experience hyperinflation, so it’s hard to tell whether he’s looking at correlation or causation.

And finally, all of Sargent’s examples — Austria, Hungary, Poland and Germany — come from post-World War 1 Europe. It’s not clear whether their experience generalizes. For example, economists who write about hyperinflation often note that these episodes usually follow wars or revolutions. But perhaps that’s an artefact of the dominance of post-WW1 Europe in the literature? A 1986 paper by Dornbusch and Fischer noted that in more recent episodes of peacetime hyperinflation in Argentina and Israel, stabilization measures looked different than in the classic cases. Maybe the causes were different too.

More recent attempts

There are a few recent papers on hyperinflation. But they tend to be dominated by theory. And as you know if you’ve ever read any macro theory, it tends to have no real predictive power. For example, a 2020 paper by Obstfeld and Rogoff constructs a model where hyperinflation might happen, or might not. Furthermore, macro models are rarely tested against data, so this paper might reach a totally inconclusive conclusion for totally wrong reasons.

There are a few other recent papers around, but most of them are not supremely enlightening. (Now just watch, someone’s going to see this post and email me an awesome paper I was previously unable to find, and I’m going to have to do a big update!)

(Update: Here is a cool 2009 paper by Sargent, Williams and Zha. They look at various hyperinflations in Latin America — most of which did not coincide with war or revolution — and do some statistical analysis to try to determine the causes. As in Sargent’s 1982 paper, they focus mainly on how to stop hyperinflations, and they find that budget balancing is important. But they also make a model of expectations, and they find that sudden surges in inflation expectations seem to kick off the hyperinflations. So that’s interesting. It suggests that austerity can be effective in halting a hyperinflation, but that unknown other stuff is involved in starting it.)

So, anyway, what kind of research should macroeconomists be doing? If it were me, I’d start with an attempt to look at a whole bunch of different kinds of data for countries that had hyperinflations, and try to observe some common patterns — what economists call “stylized facts”. Basically, just try to figure out what hyperinflation looks like.

And in fact, there is a paper that does something like this! A 2018 IMF working paper by José Luis Saboin-García tries to characterize the “modern hyperinflation cycle”.

I love you, José Luis Saboin-García! You’re a hero! You deserve a parade!

Saboin makes some progress in answering Question 2 from above. He observes that hyperinflation episodes tend to be preceded by several years — maybe 2 to 12 years — in which inflation is high but not yet “hyper”. That suggests that if the U.S. government ever starts running into fiscal trouble, it will have time to pull back from the precipice. In other words, the sides of the invisible pit might not be sheer drops, but might begin with a more gentle slope. That’s good news. (Other researchers have noticed the same.) The question is how painful it would be to get things under control if we do reach that initial stage, and what that would require.

On the matter of Questions 1 and 3, Saboin’s results are a bit less helpful to the U.S. case. Most of the regularities he notes are things that are typical of an emerging-market financial crisis — a developing country with a state-dominated resource-based economy that does lots of external borrowing and often has a fixed exchange rate. And they’re often helped out of hyperinflation with external assistance (something that the U.S.’ sheer size and centrality to the global economy would probably preclude).

Some people will look at this and say “See? Hyperinflations are something that only happens in dysfunctional developing countries! It could never happen to a huge rich industrialized nation like the U.S.! So we never have to worry about borrowing constraints at all!”

This would be a very bad takeaway, in my opinion. Assuming that things that have never happened before are utterly impossible, and then betting the entire fate of the economy on that assumption, is exactly how we got the Great Recession. Remember all the banks who built their models around the idea that house prices couldn’t fall, just because housing prices hadn’t fallen (much) in the past? That was not smart. In general, doing policies that you’ve never done before, and daring the economy to respond in ways it has never responded before, is asking for trouble.

Macroeconomists, attack!

José Luis Saboin-García is a hero, but let’s face it — we are not going to be able to formulate proper safeguards against government over-borrowing based on one IMF working paper that precisely 0.7 people will ever read. We need to get the big guns trained on this question.

Just because the U.S. hasn’t had inflation for a long time doesn’t mean borrowing constraints aren’t a pressing, even urgent research question. There are so many pieces of the puzzle that need investigating. Do deficits matter in the absolute sense, or does it just matter how much is financed by the central bank? Is the start of central bank financing of deficits what kicks off the inflation, or something else? Does it matter what government spends the money on? Are policy regime changes of the kind Sargent talks about actually detectable in the data? And if so, what do they look like? Why hasn’t Japan, with its debt of 240% of GDP, had even the tiniest glimmer of inflation?

And so on.

We need the top minds working on this now, not waiting until after disaster strikes and then analyzing it after the fact!

And maybe they’ll fail. Maybe the past simply can’t teach us much about the future. Maybe past episodes of hyperinflation simply don’t correspond to the epic unholy disaster that would happen if the world’s biggest industrialized economy decided that borrowing constraints don’t exist and that it’s time to fire up the the electronic printing presses to finance zegatrillions of new spending. Or maybe small poor countries racked by war and resource dependency and bad governance and external dependency really do have zilch to teach us, and the invisible pit is very very very very far away, so that no matter what we do, we won’t face any negative consequences in our lifetime no matter how much the federal government borrows.

Maybe the only way to find out where the invisible pit lies is to just keep walking down the corridor, so that future economists can dissect our experience and draw lessons from it.

But maybe not. If there is any helpful insight to be gleaned from the data — any scrap of information as to where the invisible pit lies — then macroeconomists should be scouring the records in search of it.

And in the meantime, if someone asks you “How much can the government borrow safely?”, just remember that the correct, canonical, scientific answer is “NO ONE KNOWS, HAHAHAHAHAHA”, followed by a strange, herky-jerky little dance representing the inherent chaos and ineffability of this mad world.

It's time to stop talking about "debt" as if it's actually any sort of debt, it's not. What we refer to as "US debt" is actually just money supply. When US "debt" is held by private individuals, it's just our savings. When its held by foreign governments, it's no different than holding cash.

Look at Japan, who has "purchased" their debt by printing money. These financial instruments are completely fungible. And it's fundamentally not "debt" because the US can *never* involuntarily default on the debt. And if the US did decide to default on some it's "debt," it would only be like burning some cash of the T-bill holder, instead of printing money to back it.

Foreign governments are gobbling up T-bills at *negative* interest rates. That's because more people want to be able to exchange things in dollars, and the T-bills are preferred to holding cash. We could also just print dollars, and get them out in circulation through government spending, or by buying back existing T-bills with those dollars.

Calling this stuff "debt" is just deceptive, and leads to bad policy. We need to start calling it "money supply." Our "debt" is really just printing money, with the side effect of the government setting the minimum borrowing rate that banks will borrow at. T-bills are just dollar bills with interest side effects.

> We need the top minds working on this now, not waiting until after disaster strikes and then analyzing it after the fact!

This sounds a lot like longtermist effective altruists' calls to work on reducing existential risks now, since we *cannot* wait until an "existential" disaster (either extinction or an equally bad outcome like the permanent collapse of civilization) destroys our whole future to start preventing it.