Why China's economy ran off the rails

A short, simplistic, but fairly reasonable story.

OK, so I guess I’m writing about China one more time. For those subset of readers who are rolling their eyes and saying “Oh my God, ANOTHER China post?”, all I can say is, when there’s a big event that’s all over the news, people need a lot of explainers. And right now, the big event that’s in the news is China’s economic crisis.

This is a pretty momentous happening, since a lot of people had started to believe — implicitly or explicitly — that China’s economy would never suffer the sort of crash that periodically derails all other economies. That was always wrong, of course, and now the bears are coming out for a well-deserved victory lap. But there are a whole lot of narratives out there about why China’s economy crashed — it took on too much debt, it invested too much of its GDP, it increased state control at the expense of the private sector, and so on. So I think it’s useful for me to give my quick account of what happened. If you’d prefer a deep dive, this story from the Wall Street Journal is probably the best I’ve read, while the Economist has also done some excellent reporting on what the Chinese slowdown feels like on the ground.

Anyway, OK, here is my quick story of what happened to China. In the 1980s, 90s, and early 2000s, China reaped huge productivity gains from liberalizing pieces of its state-controlled economy. Industrial policy was mostly left to local governments, who wooed foreign investors and made it easy for them to open factories, while the central government mostly focused on big macro things like making capital and energy cheap and holding down the value of the currency. As a result, China became the world’s factory, and its exports and domestic investment soared. As did its GDP.

At this time there were also substantial tailwinds for the Chinese economy, including a large rural surplus population who could be moved to the cities for more productive work, a youth bulge that created temporarily favorable demographics, and so on. China was also both willing and able to either buy, copy, or steal large amounts of existing technology from the U.S. and other rich countries.

Meanwhile, during this time, real estate became an essential method by which China distributed the gains from this stupendous economic growth. It was the main financial asset for regular Chinese people, and land sales were how local governments paid for public services.

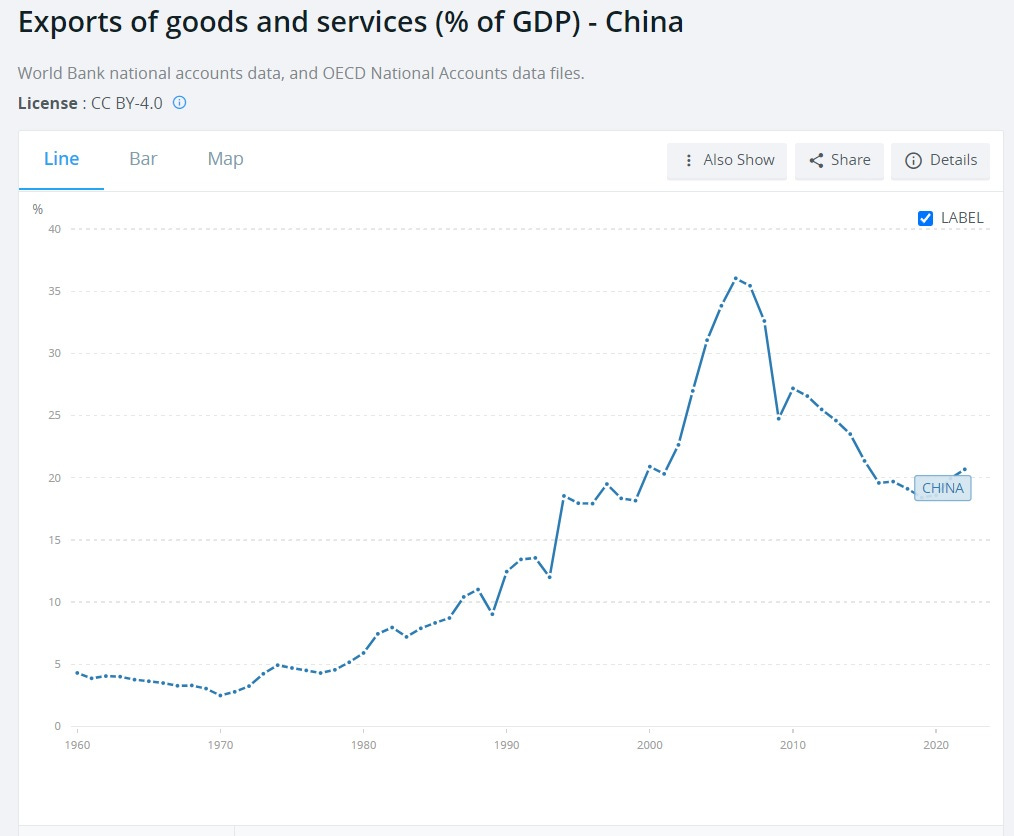

Then the 2008 financial crisis hit the U.S., and the Euro crisis hit Europe. The stricken economies of the developed nations were suddenly unable to keep buying ever-increasing amounts of Chinese goods (and this was on top of export markets becoming increasingly saturated). Exports, which had been getting steadily more and more important for the Chinese economy, suddenly started to take a back seat:

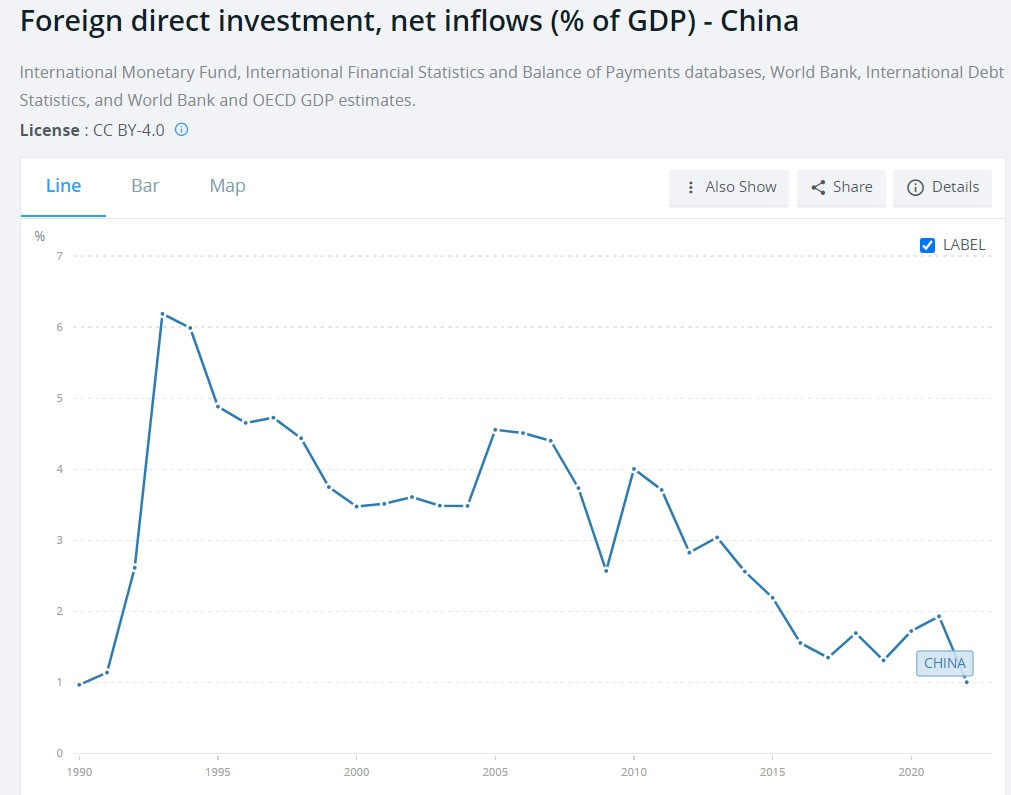

Foreign direct investment started to taper off as a percentage of China’s GDP around 2010:

The diminishing returns to the exports-and-FDI growth strategy of the 90s and 2000s threatened to slow down China’s growth by quite a lot. So China’s leaders pivoted, replacing some of the investment in factories with investment in real estate. The government told banks to lend a lot in order to avoid a recession, and most of the companies they knew how to shovel money at were in the real estate business in some way. That strategy was successful at avoiding a recession in 2008-10, and over the next decade China used it again whenever danger seemed to threaten — such as in 2015 after a stock market crash.

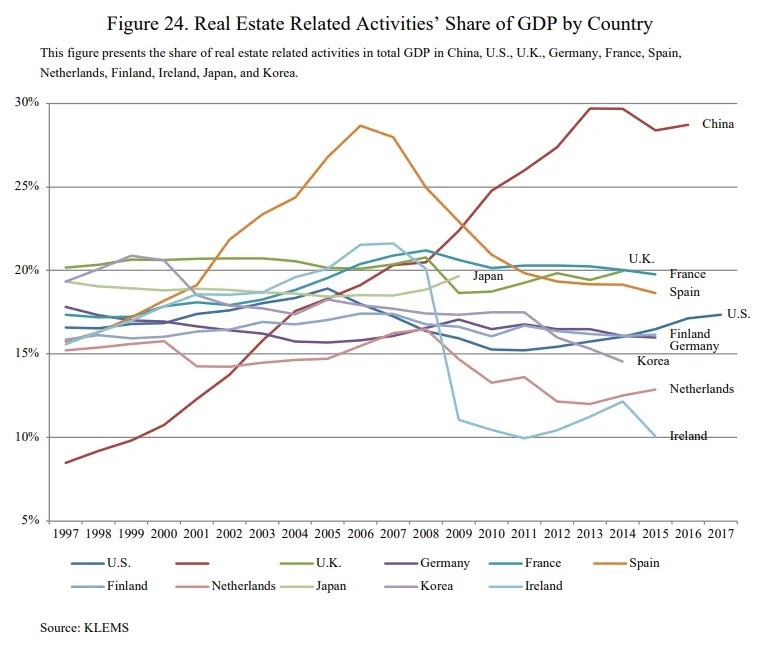

Maybe China’s leaders were afraid of what would happen to them if they ever let growth slip, or maybe they didn’t really think about what the costs of this policy might be. In any case, China basically pivoted from being an export-led economy to being a real-estate-led economy. Real-estate-related industries soared to almost 30% of total output.

That pivot saved China from recessions in the 2010s, but it also gave rise to a number of unintended negative consequences. First, construction and related industries tend to have lower productivity growth than other industries (for reasons that aren’t 100% clear). So continuing to shift the country’s resources of labor and capital toward those industries ended up lowering aggregate productivity growth. Total factor productivity, which had increased steadily in the 2000s, suddenly flatlined in the 2010s:

These TFP numbers are a little suspicious, but more optimistic sources also record a sharp productivity slowdown in the 2010s.

This productivity slowdown probably wasn’t only due to real estate — copying foreign technology started to become more difficult as China appropriated all the easier stuff. Nor was productivity the only thing weighing on China’s growth — around this same time, surplus rural labor dried up. Anyway, put it all together, and you get a slowdown in GDP growth in the 2010s, from around 10% to around 6% or 7%:

But 6-7% is still pretty darn fast. In order to keep growth going at that pace, China had to invest a lot — around 43% of its GDP, more than in the glory days of the early 2000s, and much more than Japan and Korea at similar points in their own industrial development.

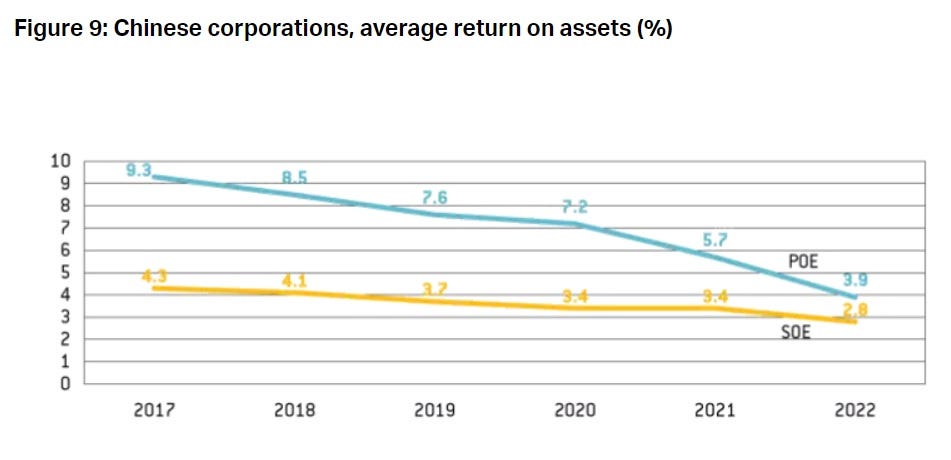

Only instead of deploying that capital efficiently, China was just putting it toward increasingly low-return real estate. The return on assets for private companies collapsed:

Much of this decline was due simply to the Chinese economy’s shift toward real estate; if you strip out real estate, the deterioration in the private sector looks much less severe.

A lot of commentators will talk about China needing to take out more and more debt in order to keep generating a given amount of growth. I prefer to think in terms of investment. Because of its pivot from exports to real estate, China had to keep investing more and more capital in physical structures — apartment buildings, offices, stores, and infrastructure — in order to keep growth in the 6-7% range.

Or as the World Bank put it in 2020:

Much of the increase in the [amount of new capital needed to generate a given amount of growth] can be explained by lower returns to capital in infrastructure and real estate. During the years of rapid deterioration in the [incremental capital-output ratio], the composition of investment in China changed significantly. The share of capital formation in the business sector declined, while the shares of infrastructure and housing increased.

Anyway, at the same time that China’s pivot to real estate was slowing its productivity growth, it was also giving rise to a gigantic bubble. Because real estate was also Chinese people’s main savings vehicle, people were pouring their life’s savings — and their parents’ life’s savings, and their grandparents’ life’s savings — into buying apartments that they expected to serve not only as a place to live but as their nest egg for retirement (or possibly into buying real-estate-backed bonds from shadow banks).

And just like in America before 2008, a long boom probably tricked Chinese people in the 2010s into thinking that real estate prices would always keep going up — a phenomenon known as extrapolative expectations. As a result, people were paying anywhere from 18 to 50 times their annual income to buy an apartment in China’s top cities — far more than in San Francisco or New York.

So basically there was a gigantic bubble, and eventually that bubble had to pop. It’s not clear exactly what popped it — some blame Xi Jinping’s ham-handed industrial crackdowns in 2021, while others say that it was a natural result of China reaching developed-country levels of living space per person. We’ll probably never know. But it did pop, and now prices are declining and debts aren’t being paid back and developers are defaulting and shadow banks are defaulting and lending is plummeting, etc. etc. — all the same stuff that America saw in 2008-10 and Japan experienced in the early 90s. At this point, real estate bubbles and their aftermath are a very recognizable phenomenon.

So even as the pivot to real estate was adding to a long-term slowdown in China’s growth, it was also generating a bubble that would eventually cause an acute short-term slowdown as well. If there’s a grand unified theory of China’s economic woes, it’s simply “too much real estate”.

But why? What about China’s political economy sent them down this path? As America and Japan learned, real estate bubbles are something that happens to a lot of economies, but China’s real estate sector looks far more swollen. I think there are at least two basic reasons China let that happen.

First, refusing to pump up real estate in response to the end of export-led growth, the 2008 financial crisis, and later economic threats would have run the risk of a recession. In a democracy, a recession usually gets the ruling party thrown out of office; in an autocracy, they might get thrown out of a window instead. So China’s authoritarian system might have forced them to act in a short-sighted fashion, tolerating zero risk of recession even though doing so had long-term costs.

The second reason China pivoted to real estate is that this helped local governments pay for things. China has no property tax, so local governments need to sell land in order to pay for services. Showering developers with bank loans undoubtedly raised the demand for land, allowing local governments to collect more revenue.

So anyway, this is my simple story for why China’s economy slowed down so early in its development and then experienced a crash in the early 2020s. Export-led and FDI-led growth can’t go on forever, and when they run out, it’s better to divert capital toward building a well-balanced economy of high-tech manufacturing and services than to shower it on property developers and shadow banks. Pivoting to real estate will come back to bite an economy eventually. For all the talk of China’s “100-year plans” and whatnot, they fell into a pothole that was right in front of their feet.

The real story is going to be more complicated than that, but if you want a quick-and-dirty explanation of why China’s crash is on everyone’s minds right now, I think the story of the pivot to real estate is probably the best simple story you can tell.

Actually, the real story is simpler ...

1) Through a "copy me" structure China built an export led economy focused on providing the world with two values (lower cost, nearly infinite labor). The world was only too happy to engage because this offered a "tool" not available in their native countries.

2) As the Chinese tried to move up the value chain and became more competitive, it became harder and harder to continue the same level of growth. They had to move up the value chain because lower cost geographies existed. Artificial means (currency manipulation) used to maintain cost advantages. With some notable exceptions, the economy built had very little inherent innovation which could be competitive on a world-wide basis.

3) Initial investments in infrastructure had massive productive value (because of the starting base). However, without market discipline and with ideas of full employment, a classic debt/real estate bubble emerged. In these bubbles, structures are built for the sake of building them and not their economic value.

4) Having exhausted domestic construction (many empty buildings), a brilliant idea... Belt/Road initiative! Chinese developers are so competitive that they have to do work for free for people who cannot possibly pay them back, but let's pretend the loans are good. Belt/Road projected as sign of Chinese power, but in reality, it is just feeding the debt beast.

Finally, believing its own media headlines of Chinese power, government takes an aggressive posture. Foreign direct investment plummets. it turns out it is not that hard to move low-value supply chains. Chinese citizens, recognizing the situation far better than their government, shutdown and go into "depression" mode. Demand plummets. Outsourcing of manufacturing accelerates. For their own survival, Chinese companies aid in this process. The whole neighborhood turns hostile.

Underneath, there are lots of green shoots (EV, Solar, etc), but will they survive?

Excellent quick-and-dirty explainer. Now do a post on how bad you think it's going to get. I'd be interested in your take.

I should probably say, I'm one of those people who has been looking at the Chinese economy, and in particular the real estate/infrastructure-investment bubble (the unused airports, unused high-speed rail lines, etc), with ever-mounting astonishment, for years. I kept thinking it had to pop, but the CCP kept finding ways to inflate it further. If they have finally run out of levers to pull, if the entire property sector is now finally collapsing, I can't see how it won't pull the whole country down the toilet after it. This looks like the mother and father of all property crashes, it is going to hit EVERYONE in China extremely hard (property was the only place a normal person could invest), and there is nobody available to blame except the CCP. How does the CCP survive that, when no young person has ever experienced serious recession before, and the youth employment rate, going INTO this recession, is already so alarmingly high that they have stopped publishing the figures? I fear the mandate of heaven may be withdrawn at some point in the next five years.

Of course, the CCP has made sure there is no remaining organisation, political, social or religious, of any kind in China who could take over any of the CCP's functions – so a massive public collapse of confidence in the CCP, à la East Germany in 1989, is unlikely lead to anything good in the short term.

Anyway, I would value your thoughts! What am I missing? How can the CCP avoid the menacing train of consequences currently steaming down the track towards them?