At least five interesting things for the middle of your week (#31)

Indian poverty reduction, America's friends, Canada's economy, Europe grows a spine, and Japan's DARPA

Hey, folks! I’ll be headed to Japan later this week for cherry blossom season. I plan on doing a hanami (cherry blossom picnic) with Noahpinion blog and Twitter fans sometime the weekend of the 29th, so I’ll let you know when that is!

Here’s an episode of Econ 102, where Erik Torenberg and I discuss AI and jobs with Nathan Lebenz:

This episode led to my recent post about AI and comparative advantage, which you should check out if you haven’t already!

And here’s an episode of Hexapodia, where Brad and I talk about the book Power and Progress:

Anyway, on to this week’s list of interesting things. I’m in the mood to talk about international stuff today.

1. India’s amazing poverty reduction

For the past few years, there has been a debate over just how much India has actually managed to reduce poverty. Everyone knows it has reduced it a lot, but some people claim that the true numbers are less impressive than the eye-catching headlines. Well, we have some new numbers, with some methodological improvements. And guess what? India’s poverty reduction has been even more impressive than the headlines had suggested! Surjit Bhalla and Karan Bhasin have the scoop:

India has just released its official consumption expenditure data for 2022-23, providing the first official survey-based poverty estimates for India in over ten years…India [shifted to] the more accurate Modified Mixed Recall Period (MMRP), which asks household consumer expenditure on perishables (for example, fruits, vegetables, eggs) for the last 7 days, durable goods for the last 365 days, and expenditure on all other items for the last 30 days…[This method is] the standard in other countries…

High growth and [a] large decline in inequality have combined to eliminate poverty in India for the PPP$ 1.9 poverty line [in 2011 dollars]…For the PPP$ 3.2 line, [poverty] declined from 53.6% to 20.8%…Note that these estimates do not take into account the free food (wheat and rice) supplied by the government to approximately two-thirds of the population, nor utilization of public health and education…

The data show a strikingly lower number of poor people in India, at both thresholds, than those estimated by the World Bank. That institution relied on the Consumer Pyramids Household Survey, a privately provided data source, to derive poverty numbers of 10% (at $1.90) and 45% (at $3.20) in 2020, despite well-known problems with that data explained by Bhalla, Bhasin and Virmani (2022)…

Poverty HCR (2011 PPP 1.9$)

Poverty HCR (2011 PPP 3.2$)

That’s absolutely stunning. The extreme poverty reduction that India managed to accomplish in the 2010s is similar to what China managed to accomplish a decade earlier:

India is lagging a bit behind China on GDP growth since market liberalization. But on poverty reduction, it’s keeping pace.

And importantly, India managed to decrease poverty this much while also decreasing inequality. Bhalla and Bhasin argue that this was due to the Indian government’s focus on redistribution to rural areas:

An unprecedented decline in both urban and rural inequality. The urban Gini (x100) declined from 36.7 to 31.9; the rural Gini declined from 28.7 to 27.0. In the annals of inequality analysis, this decline is unheard of, and especially in the context of high per capita growth…

The relatively higher consumption growth in rural areas should not come as a surprise given the strong policy thrust on redistribution through a wide variety of publicly funded programs. These include a national mission for construction of toilets and attempts to ensure universal access to electricity, modern cooking fuel, and more recently, piped water. As an example, rural access to piped water in India as of 15th August 2019 was 16.8% and at present it is 74.7%. The reduced sickness from accessing safe water may have helped families earn more income. Similarly, under the Aspirational District Program, 112 districts of the country were identified as having the lowest development indicators. These districts were targeted by government policies with an explicit focus on improving their performance in development.

Recall that China’s poverty decrease followed a more typical pattern: the economy was liberalized, the rich got much richer much faster, the poor were uplifted but more slowly than the rich, and inequality soared. We’ve gotten used to thinking that soaring inequality is the inevitable price of rapid economic development, but India is proving otherwise.

Perhaps democracy is useful for development after all.

2. America’s friends and enemies

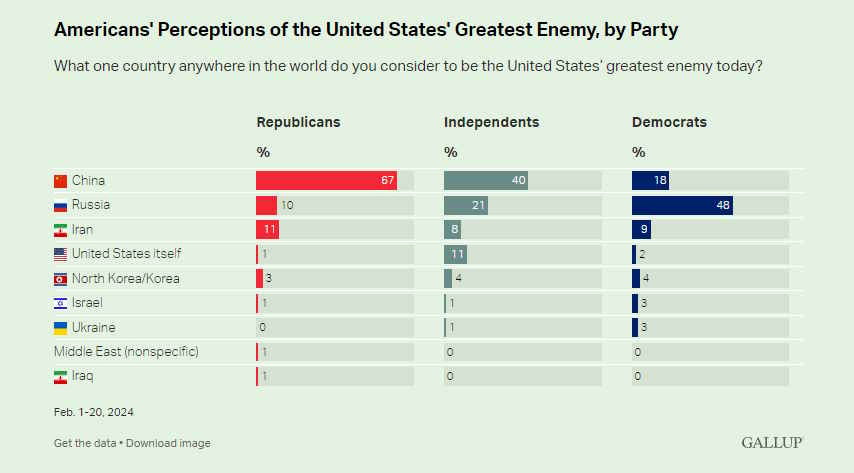

Gallup has a new poll out, asking Americans about which countries they like, and which they perceive as enemies. The headlines are mostly about the “enemies” question, which I guess isn’t surprising, because “enemy” is a strong and frightening word. Anyway, the story there is that Republicans think China is our biggest enemy, Democrats think Russia is our biggest enemy, and Independents generally agree with Republicans but also are more likely than either party to think that the U.S. itself is our own greatest enemy:

Honestly, I have to give it to the Independents here.

But I also think that Americans (and the American media) spend too much time thinking about who the country’s enemies are, and not nearly enough time thinking about who its friends are. Thinking about our enemies can put us into a “go it alone” mindset, which is fatal when confronting a country that’s much bigger than we are, like China. America is a medium-sized country that will need many allies to prevail in Cold War 2 — and to deter a hot war.

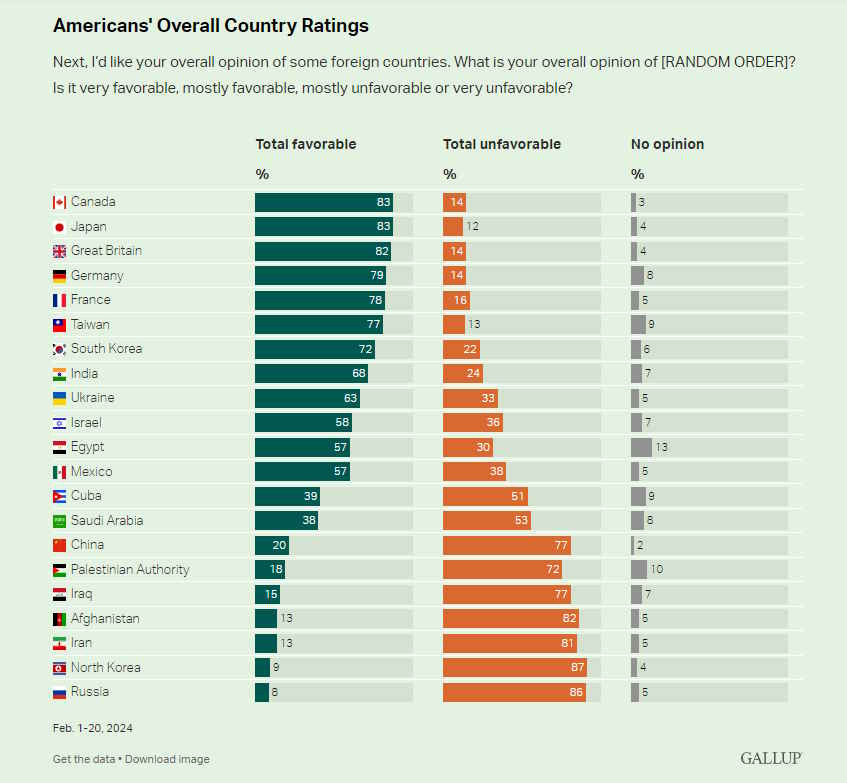

That means we have to overcome our isolationist mindset — the false comfort of thinking that we have two big oceans on either side that will protect us from conflicts in Eurasia. We have to think about who we can cooperate with. So it’s good to see that Gallup also asked Americans which countries they had favorable attitudes toward:

This is a good start, though I wish pollsters would ask Americans about Indonesia, Poland, Vietnam, Turkey, and Pakistan. I’m pleasantly surprised at how few respondents had “no opinion” about any of these countries, so I think there’s room to add more here.

Anyway, we can see that Americans tend to like democratic countries and dislike autocratic ones. There isn’t an obvious bias toward European countries, since Russia ranks at the very bottom while Britain, France, and Germany rank near the top. There is probably a slight dislike for Middle Eastern countries, which hopefully will push Americans to want to recommit our resources away from that region.

Most interestingly, most well liked country, as measured by the difference between favorable and unfavorable, is Japan. Americans really, really, really like Japan. As they should! First of all, this means that American politicians who try to pander by raising protectionist concerns against Japan — Biden’s opposition to Nippon Steel’s acquisition of U.S. Steel, or Trump’s tariffs on Japanese steel — are probably barking up the wrong tree. And second, it means that we in the media should probably talk more about Japan’s critical security interest in Taiwan.

Anyway, it’s also good to see that Americans are overwhelmingly positive about India, Taiwan, and South Korea. Our leaders should make a greater effort to harness that positive sentiment and push for closer economic cooperation with those countries.

3. What’s the matter with Canada?

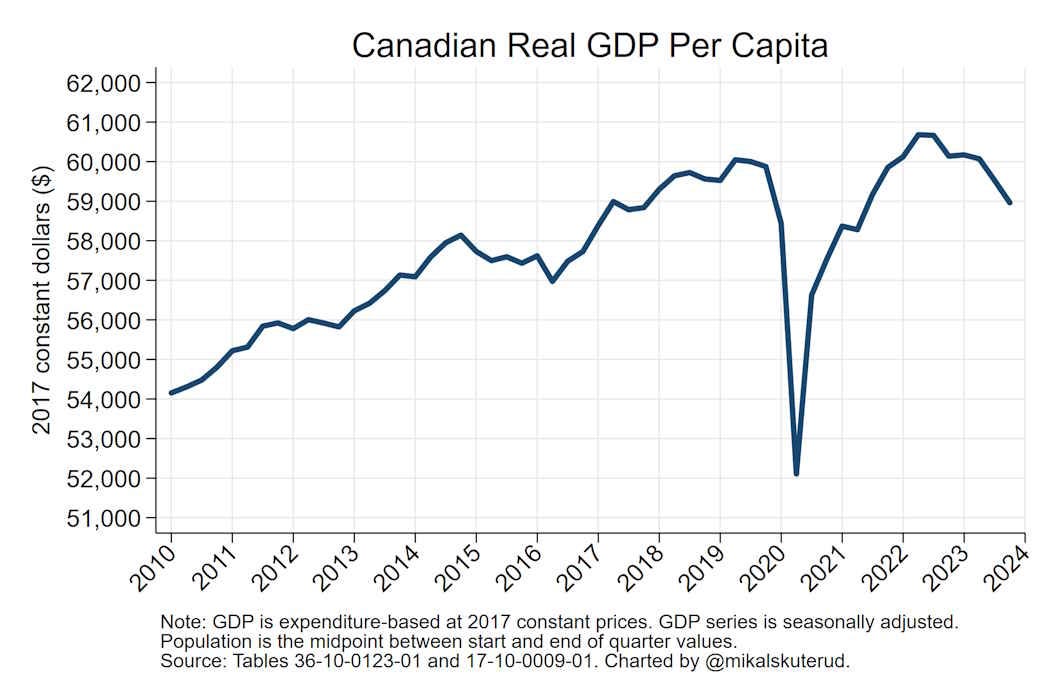

Many people are worried about Canada’s economy in recent months. The country’s real per capita GDP — the most common measure of living standards — has been falling for over a year now:

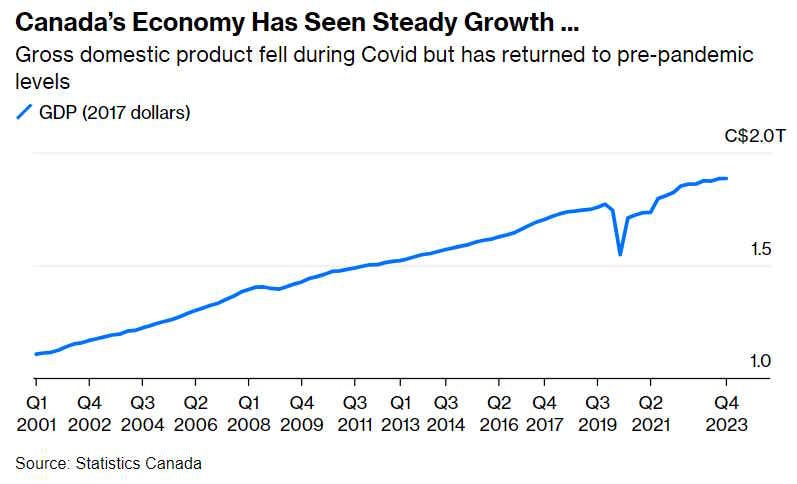

In a recent Bloomberg op-ed, Tyler Cowen tells us not to worry — Canada’s GDP, and its median income, are still growing. But honestly, his data is not convincing. First of all, the chart he posts is of total GDP, not GDP per capita:

You can see the worrying flattening over the last two years. But during those years, Canada’s population continued to grow! So per capita living standards were shrinking!

Tyler also posts a chart of rising median incomes in Canada. But his chart ends in 2021 — before the current growth slowdown began! So that’s not very reassuring either.

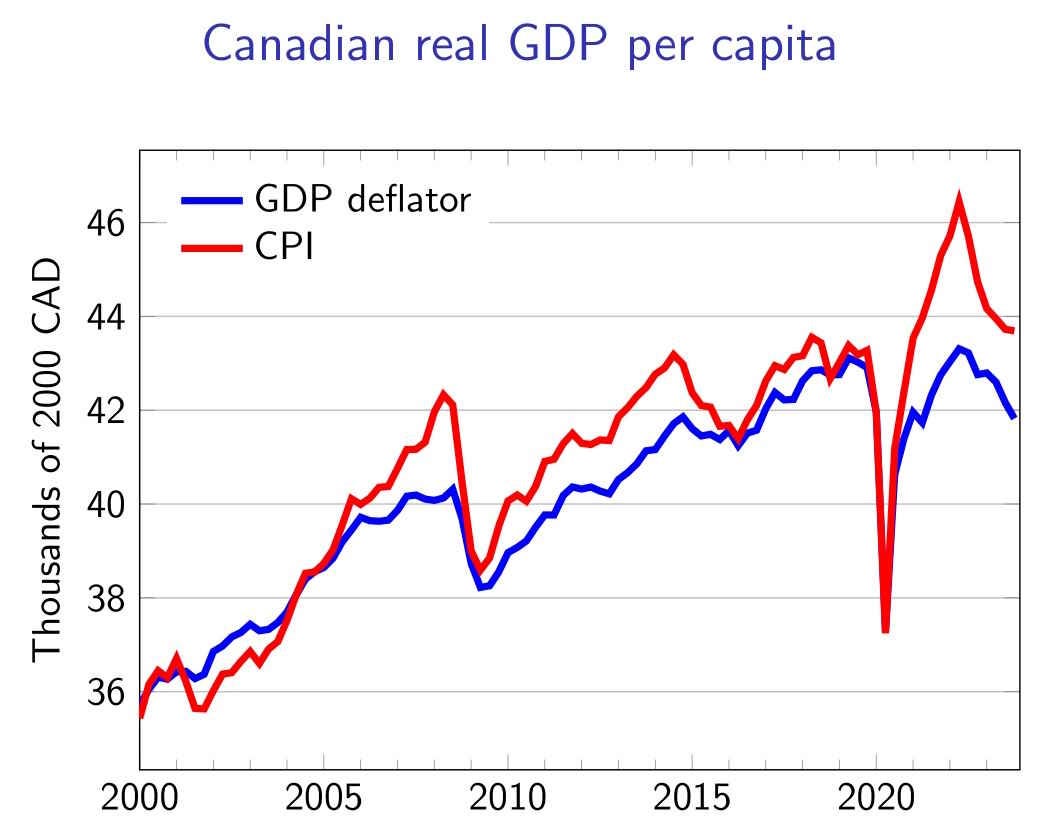

Tyler notes that real GDP per capita is adjusted for inflation using the GDP deflator, rather than consumer prices. He links us to a thread by Canadian economist Stephen Gordon, who argues that the prices of the goods Canada sells overseas are less important than the prices of the goods Canadians buy, so that we should look at real GDP per capita deflated by the consumer price index instead.

And yet when Gordon performs this calculation, the results look even more worrying! Canadian CPI-deflated real GDP per capita absolutely plummeted over the past two years, and is now barely higher than it was a decade ago!

Contrast this with the U.S., whose real per capita GDP just keeps going up and up:

Tyler is certainly right that Canada is still an extremely nice place to live. But when your per capita GDP falls like a rock for two years, and barely grows at all for a decade, it should definitely prompt some serious thinking.

What’s going on with Canada’s economy? It’s not clear. A drop in exports was part of the most recent quarterly weakness, driven by oil and cars. That illustrates Canada’s dangerous dependence on petroleum — both its reliance on oil exports, and its status as a hub for internal combustion car manufacturing in an era when everyone is switching to electric. Oil also helps explain the stagnation of Canadian GDP since 2014; that’s when oil prices fell from their very high early 2010s plateau. “Petrostate” is not an economic strategy that Canada should pursue.

But Canadian consumption and investment are also stagnant or falling right now. This could reflect the effect of higher interest rates, though it’s not clear why that would affect Canada more than the United States (both countries are running large fiscal deficits). It could also reflect diminished expectations about Canadian oil and car exports going forward. Another long-term problem, which Tyler mentions, is Canada’s dysfunctional housing market and refusal to build new housing supply.

Anyway, I don’t have a clean and obvious answer to the question of “What’s the matter with Canada?”, but I do think it’s very much worth worrying about.

4. Has Europe finally awakened?

For about a year now, I’ve been yelling that Europe has to pull together and make a stand against Russia. With the U.S. divided by internal political turmoil and likely to need all its strength to deter China over in Asia, Ukraine needs Europe to step up and be the arsenal of its defense. This isn’t just for altruistic reasons, or to defend some sort of rule-based international order; it’s painfully clear that if Ukraine falls, Russia will continue its push into East Europe, threatening the economy and the physical security of every other country in the region.

But Europe hasn’t yet woken up to the full magnitude of the threat it’s facing, or the political will that will be necessary to turn things around. A Chinese defense commentator recently dismissed the region with maximum scorn:

In this military conflict, Europe is undoubtedly the big loser … Before the Russia-Ukraine conflict, Europe was the largest economy in the world. However, it is now steadily declining. Political discord is rife, its security is not ensured and there is a possibility that it might collapse and fall apart.

It’s up to Europe to prove this guy wrong, but for the past two years his perspective has proven disturbingly accurate.

Germany, for example, is Europe’s industrial heartland, but it’s in a period of deep dysfunction. Dependence on Russian gas, a dogged insistence on shuttering nuclear power plants even in the middle of an energy crisis, and an almost religious commitment to fiscal austerity has hobbled German industry. Meanwhile, German defense policy is a lot less focused than it should be; Rheinmetall, the German defense manufacturer, produces more artillery shells than the entire U.S., but 40% of that production goes to countries other than Ukraine.

This is not to say Germany has been lagging or useless on the Ukraine issue — it’s given quite a lot of aid. But overall it’s an economically dysfunctional country with an understandable deep historical reluctance to embrace national assertiveness or get into a conflict with the Russians.

France, on the other hand, has few such qualms. French President Emmanuel Macron has suddenly become much more hawkish on Ukraine, calling the Russian threat to Europe “existential”, refusing to rule out French entry into the war, and responding to Russia’s nuclear threats by saying “Our own nuclear weapons give us security.” France isn’t able to match Germany’s economic or demographic heft, but it’s suddenly showing the political leadership that Germany has been structurally unable to show. Macron and Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk recently met with Scholz to emphasize a message of European unity on the Ukraine issue; it seems pretty clear that there was some substantial jawboning going on. Meanwhile, even as Germany shutters nuclear plants, France is building more of them.

I should also add that it’s not just France showing signs of waking up here. Some smaller European countries are stepping up as well. Czechia is leading a big effort to supply Ukraine with artillery shells. And of course Poland, who is in Russia’s direct line of fire, has massively increased its own defense spending. The Baltics and Romania have done so to a more moderate extent.

But without the leadership of the big countries — France, Germany, and the UK — the small countries of Europe can’t stand against Russia. So it’s very important that France is stepping up here. Perhaps the traditional French desire to have a foreign policy independent from America’s caused Macron to step up just when it seemed like the U.S. was stepping back. In any case, competition between states has always been Europe’s great strength; the hope is that France’s entrepreneurship in the “standing up for Ukraine” space will induce Germany and others to follow suit.

Actions speak louder than words, though. European countries need to increase defense spending by quite a lot — not just to the 2% NATO target, but to 3% or more. Germany has pledged to do this but is lagging severely. And European companies like Rheinmetall need to stop exporting ammunition that could be used in Ukraine to third countries, and start sending all of these to Ukraine.

European countries also need to tend to their own industrial bases, ensuring that critical defense-related industries don’t get exported to China. They need to ensure adequate energy supply by combining nuclear, solar, wind, and imported LNG. They need to very quickly expedite permitting and other regulatory barriers to defense and defense-related manufacturing.

In other words, Europe is stirring at last, but it hasn’t entirely woken up yet. Hopefully Ukraine can hold out until sufficient urgency has overcome the inertia in Paris, Berlin, and London; otherwise, Europe will be facing Russia on the fields of Latvia, Estonia, Lithuania, and Poland.

5. Japan’s answer to DARPA

Against all odds, I’m suddenly finding myself feeling optimistic about Japan. The country is doing a good job encouraging a return of the semiconductor industry after years of disinvestment, its birth rate is low but higher than other East Asian countries, and I’m hopeful that it’s high-skilled immigration policies will eventually start to bear fruit.

This week I read a story that gives me one more reason for optimism. I’ve long argued that a Japanese defense buildup would allow the government to step up military R&D, much as the U.S. has done via DARPA and other defense research programs. This wouldn’t just enhance Japan’s security, but would allow it to regain a technological edge in various dual-use industries, just as DARPA led to the creation of the internet.

Well, Japan is doing something along these lines:

Japan's Ministry of Defense has doubled joint research projects with the private sector, Nikkei has learned, working with such partners as Hitachi and Mitsubishi Electric to hone technologies like drones and AI.

The ministry was involved in about 30 such projects in fiscal 2023, the most ever and up from 14 a year earlier.

Through its Advanced Technology Bridging Research program, the ministry teams up with businesses to develop defense applications for the latest technologies…The aim is to promote homegrown dual-use technologies that can boost the Japan Self-Defense Forces' deterrence and response capabilities…Businesses, meanwhile, can use these innovations to create new products or cultivate new industries. Working with the public sector from the research stage makes it easier to gauge demand and potential profits, helping to avoid the "valley of death" that often stands between the development and commercialization of new technology.

This is a little different from the way DARPA does things. DARPA tends to do the initial research in academic labs, while Japan’s Advanced Technology Bridging Research program focuses more on corporate labs. This is in keeping with the general pattern of research in the two countries; America is more academic, Japan is more corporate. But there are a lot of similarities, too — both DARPA and Japan’s ATBR bring together teams that include academics, as well as researchers from different corporate labs.

What’s exciting about this new initiative is its focus on the drone field. Japan used to be a powerhouse of the global electronics industry, outcompeting America in many markets. It then lost this leadership, first to South Korea and Taiwan, then to China. But Japan still has many of the basic advantages that make it a natural leader in electronics — a lot of good engineers, a streamlined and efficient process for building factories, a lot of specialized suppliers, and a geographic location within the Asian electronics supercluster. If any democratic country can develop a drone industry to match China’s, or at least blunt its monopoly, it’s probably Japan. This will be very important for the free world’s security, since drones are taking over warfare at a rapid clip.

In any case, I would like to see a lot more ATBR efforts focused generally on the space of electronics and other physical technologies. Japan used to have a massive advantage in this space, and with the right policies, it could regain this niche. Defense research can be a very powerful tool for helping an industry catch up to the technological frontier.

The thing with Canada...there has been a massive influx of people into it. Greater immigration then ever, 1 million new Canadians over the past two years, a 2.5% increase to the population from immigration alone. That's a good thing.

But that's a lot of people added to the denominator whose contribution to the economy is probably still low. Does that skew the stats? Would we expect GDP per capita to fall with such an influx even if there's nothing to panic about? Is there a lag?

Of course, our disastrous housing policies might mean that these people never get to become a productive part of the economy like my parents did, but that's a whole other issue and would not be in the stats yet.

I'm not opposed to Americans having "no opinion" when pollsters ask them how they feel about Poland or Vietnam. In most cases that's the appropriate response given how much they know about those countries.