Here...comes...INDIA!!!

The world has a new largest country, and it's on the move.

The United Nations estimates that India has now surpassed China as the world’s most populous country — or, as we colloquially say, the world’s “largest” country.

Obviously, crossing this threshold doesn’t mean much in practical terms. Being a tiny bit bigger than China doesn’t really change anything, and India has just about as many people as it did a year ago. But the flurry of news stories accompanying the event is a wake-up call for the world: India has arrived on the world stage, in a big way.

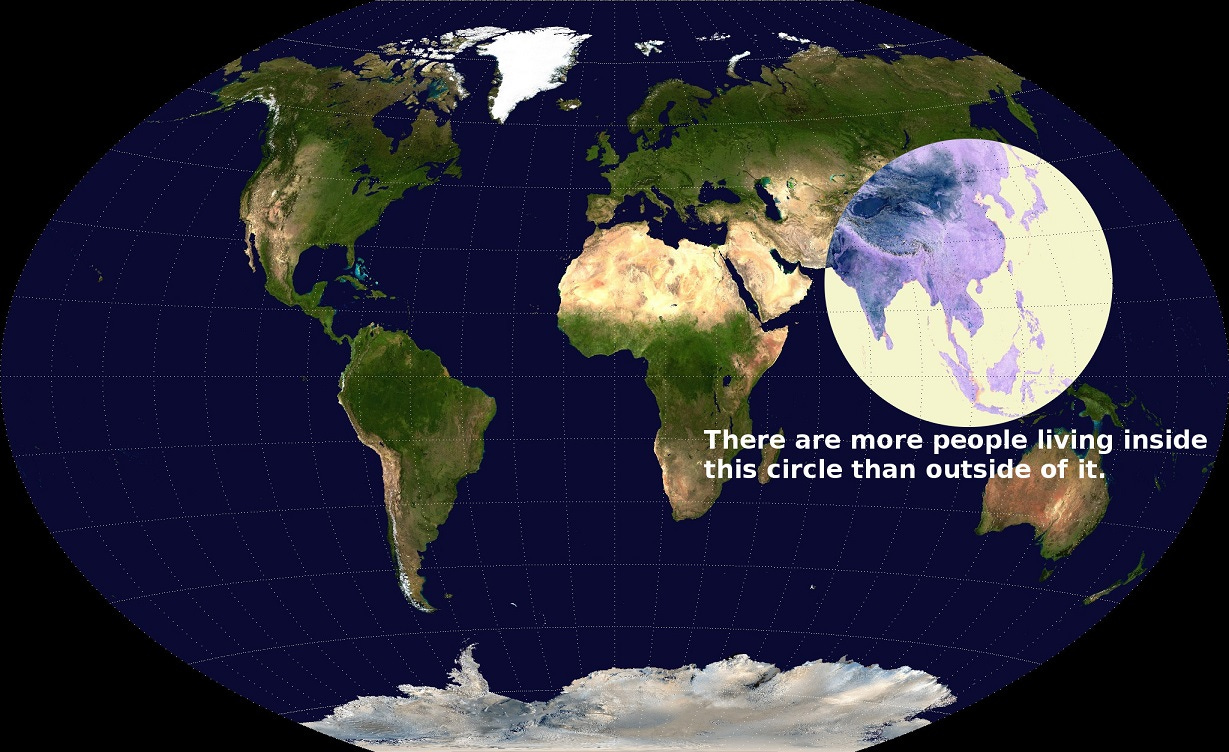

What does that mean? Well, a whole lot of stuff. More stuff than I can summarize or even mention in a single blog post. There was a quote attributed to Napoleon two centuries ago: “Let China sleep, for when she wakes, she will shake the world.” Well, China did wake up, and the world has been shaken. The whole economic landscape of the planet, the geopolitical balance of power, and even the Earth’s environment have been irrevocably changed in the last three decades by the addition of 1.4 billion human beings to the ranks of the (more or less) developed world. Now India brings another 1.4 billion, eager to join those ranks. Get used to seeing a lot more graphs with this basic format:

India’s population is also much younger. As The Economist recently reported, China’s population is concentrated in the 30-60 age range, while India’s people are mostly between 0 and 40:

This is world-shaking not just because of the sheer numbers of people involved, but because of the prospects that those 1.4 billion will become key contributors to the global economy and key actors on the stage of global politics, as China’s have.

India has always been there. The difference is that the world can no longer choose to ignore it.

India’s growth has been truly spectacular

India’s economic rise tends to get overshadowed by China’s. There are a number of reasons for this, but the simplest one is that India started its period of rapid growth about 10 years later, and has grown at around 7% rather than the 10% that China mustered for decades. But that 7% growth adds up, and in terms of living standards, India as of 2019 was about where China was 12 years earlier, on the eve of the global financial crisis:

(The same is true when you look at GDP per capita at market exchange rates instead of at purchasing power parity.)

In 2007 it was already clear that China was a big deal, and in 2023 it should already be clear that India is a big deal.

The first and most important consequence of this spectacular economic growth is that India, a country once famed for its desperate poverty, has made enormous strides in lifting up its poorest people. The most optimistic estimates, from the World Poverty Clock, predicted in 2018 that India would almost totally eliminate extreme poverty by 2022. More realistic recent estimates from the World Bank — taking Covid into account, and using better data — still conclude that poverty reduction has been spectacular. Here’s a graph through 2019:

Nor is it pure unfettered capitalism that has produced this result — even the libertarian Cato Institute admits that government transfers have played a key role in spreading India’s burgeoning wealth to the least fortunate.

Now, it’s an open question as to whether this rapid growth can continue. Unlike China, India has grown to its current level without industrializing — that is, without increasing manufacturing’s share of the economy. In a (long) recent post, I wrote about the prospects for India to turn this situation around and become another “workshop of the world”:

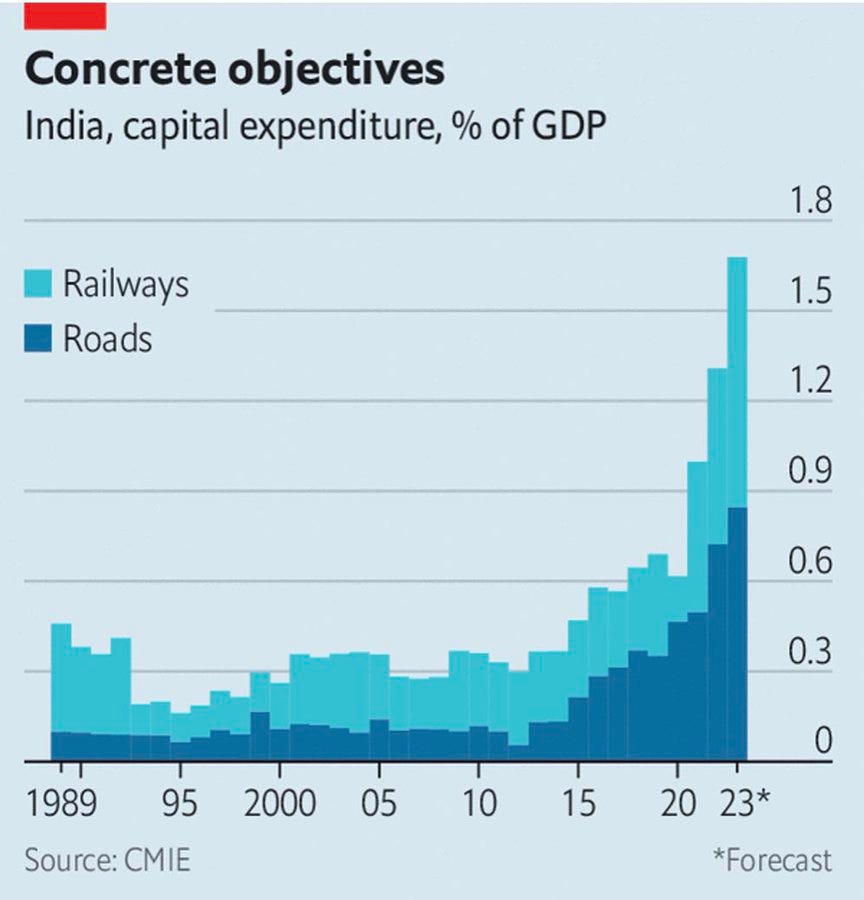

I won’t rehash that post here, but basically, I think India has most of the raw ingredients necessary to industrialize. In particular, it has built an impressive amount of infrastructure in recent years, and is building much more, shoring up a key longstanding weakness:

In addition to a huge number of new highways, India also has a bunch of nice new trains. Here’s what an Indian train looks like now:

And high-speed rail is being built, using the same trains as Japan’s shinkansen. The India of unreliable slow trains and dirt roads is rapidly vanishing into history.

Access to tap water has also improved rapidly.

If India has one remaining weakness, it’s education. I believe that eventually the government will prioritize education the same way it has prioritized building roads and trains.

Not everyone shares my optimism. A spokesperson for the Chinese foreign ministry, reacting to the news that India had the world’s largest population, recently sniffed that “Population dividend does not depend on quantity but also quality” — not the most diplomatic of statements, to say the least. In the West, those on the political Left have a curious tendency to downplay India’s growth and pooh-pooh its future chances. It is up to India’s leaders to prove these naysayers wrong.

But I am reasonably confident that they will, and the reason for my confidence has nothing to do with willful optimism or a mystical faith in the effectiveness of India’s people and India’s government. The reason is called “agglomeration effects”.

India as production platform and a market opportunity

Agglomeration effects are pretty simple to understand. Companies want to be located close to their customers, workers, and suppliers. People — who are both workers and customers — want to be located close to their employers and to the companies that sell them stuff. And financial capital wants to send money to where companies are locating their factories and offices. Taken all together, these effects are a powerful reason that cities exist, and that economic activity clusters in certain countries. When you add in clustering effects — the tendency of companies in the same industry to locate nearby to each other — the effect on the concentration becomes even more powerful.

Agglomeration in a particular region tends to have a “break point”, where a rapid snowballing of economic growth suddenly comes into effect. This explains why Asia’s growth in general has looked unstoppable in recent decades — the region has become the workshop of the world. And India is part of that region.

With production costs no longer low in China and geopolitical risk rising, multinational companies are going to be looking for alternative places to put their factories and offices. And those alternatives are likely to be in other parts of Asia, rather than in Latin America or Africa or elsewhere, in order to be close to existing supply chains and manufacturing expertise and sources of capital. And India is really the only other part of Asia whose sheer scale has any hope of matching that of China.

Multinational companies are already starting to realize that. There’s a psychological barrier to break through — executives and managers are very used to putting factories in China, and very unused to the idea that they could put factories in India. But that barrier is now being broken, thanks to the world’s top global electronics company. Apple is starting to bet big on India, shifting production of a variety of products. In 2021, only 1% of iPhones were made in India; two years later, it’s approaching 7%, with a planned increase to 40-45%. Other companies are likely to follow in Apple’s footsteps; after all, if Tim Cook thinks India is a good place to make electronics, who are you to disagree?

But Apple has more reasons to invest in India than cheap costs and geopolitical stability. It’s being drawn in by the increasingly vast opportunity of India’s domestic market. IPhones have a very small market share in India right now, but it’s rising rapidly; it’s no accident that even as Apple opens factories in India, it’s also opening new stores. Having the country as a production base will make it much easier to sell to a billion new customers.

A billion new customers. Fifteen years ago, those were the words that made Western managers and executives drool over the opportunity to invest in China, and it’s a big part of the reason why companies stay there. Now India represents an equally big opportunity.

Equally big, or maybe even bigger. Unlike China, India doesn’t mount a massive government campaign to copy (or steal) the technology of multinational companies that invest there, then transfer that technology to state-supported domestic champions. And although India has plenty of regulation, it doesn’t have China-like arbitrary state control that reaches into every economic sector in ways that are difficult for multinational companies to anticipate.

This is the essence of agglomeration, and it’s why the effect often seems like an unstoppable snowball. Companies get both workers and customers when they invest in a country. And the more workers they (collectively) employ there, the more local incomes rise, so the more tempting the local market becomes.

Of course, agglomeration can always use a bit of a push getting started. The Indian government is now making a big push to facilitate manufacturing FDI. Those incentives themselves might end up being the ones that work, or they might not, but they show that the government is thinking along the right lines .

Anyway, I don’t know if this sort of agglomeration can ultimately take India as far as it has taken China. But it’s the main reason why I’m optimistic that the Indian economy has a lot more room to run. Nor am I the only one who’s thinking along these lines — see this recent rundown by Kai Schultz and Vrishti Beniwal.

Basically, if you’re an executive or manager at a company in the U.S. or Germany or France, you need to be thinking about India now, because you know that lots of other people are thinking about India. Before, an “India strategy” was purely optional; someday soon, it may be mandatory.

It’s India’s internet now

India’s economic rise will give it greater military power and geopolitical clout on the world stage. It’s not yet one of the “poles” of the emerging multipolar world order, but if it can keep economic growth humming for another decade or two, it will be. A huge amount has been written about that, so I won’t recap it here. Instead I’ll point out another way that India will become more important to global life: culture and the internet.

India is going to be much more important than China in this regard. China should have taken over the global internet when it brought over a billion people online, but it didn’t; the country’s Great Firewall cuts off most of its population from daily discourse with the outside world. As a result, China has, to a large degree, been a silent superpower. Even as it became more important to businesses, regular people outside the country never really had a sense of what went on there, or what regular Chinese people were like.

India is very, very different. Despite a few instances of internet censorship, it has nothing like the Great Firewall. There’s also much less of a language barrier with the U.S., given how many Indian people speak English. And in just the last few years, an absolutely staggering percent of the country has gotten internet access. Here’s data from 2020:

In fact, even that data is out of date; as of 2023 there are probably over 750 million Indians online — almost three times the number in the U.S. The ever-excellent “Science is Strategic” Twitter account has a great thread with a number of other statistics illustrating the awesome size and speed of this shift.

For anyone on Twitter or in the blogosphere, the change has been very noticeable, and I would bet that something similar is happening on Reddit and elsewhere. Suddenly, a lot more of the audience is Indian, and that’s only going to be more true over time.

That means that Americans are going to understand — and are going to have to understand — a lot more about Indian political and social and cultural attitudes than we currently do. I actually think we’re very well-positioned to do this. Unlike folks in Britain and the Anglosphere, Americans have no history of colonizing India, so we won’t be able to fall back on old prejudices and stereotypes and outdated tropes. Most Americans’ only contact with Indians comes via the recent immigrants who run our big companies, do our brain surgery, make our software, and so on. If Americans have a stereotype of Indians, it’s one of economic success.

But even so, we have our work cut out for us. Indian politics, for example, is very confusing for Americans. For example, in my experience most Americans don’t know quite what to make of the country’s prime minister, Narendra Modi. Modi is extremely beloved in India — he’s currently by far the most popular democratically elected leader in Morning Consult’s global tracking polls:

But why? Is it because of all that infrastructure he’s building? Is it because he gave out all those subsidies to the poor during Covid, or improved sanitation? Or is it because of culture war issues? Do most Indians support “Hindutva”? What the heck is “Hindutva” anyway? Is Modi a bigot and/or an autocrat, as some writers and publications allege? Or is he a cosmopolitan modernizer, seeking to erase old caste boundaries, as some of my acquaintances in the tech world assert? Do I need to have a position on Aurangzeb?

Here is the world’s tallest statue, the Statue of Unity in Gujarat, four times as tall as the Statue of Liberty:

How many Americans know who Vallabhbhai Patel even was?

Americans have never been very good at knowing things like this; we are basically completely ignorant of the politics of Asian countries, and we pretend we understand European politics by applying a standard left/right lens that often proves wholly inadequate to the task. In a sense we’ve never had to be very good at understanding other countries’ politics, because we were bigger by far than any of the other countries in the community of rich democratic nations, and certainly in the English-speaking world. China might have forced us to understand it, but instead they put up a wall around their society. India has no such wall, and for the first time, Americans will not demographically dominate the internet.

Overall I think this will be a healthy thing for us. We Americans have persisted too long in thinking that America was the world. India will force us out of our provincial ignorance a bit, and remind us that we’re actually just a medium-sized country on a big big planet.

And of course America will change India too. The more money Indian people get, the more they’ll be able to spend on American cultural products — Hollywood movies, American pop music, Netflix, and so on. China is now pushing those products out of its market, but India, with its more open society, is unlikely to do so. And the Indian people talking to Americans on the internet will learn a lot about the U.S. as well.

Between economic linkages and cultural exchanges, I see the possible emergence of “Indiamerica” — a more deep and comprehensive societal integration than “Chimerica” ever was. The chances of that will be boosted, of course, if the U.S. keeps taking in Indian immigrants on a large scale. Nor do I think those influences will be limited to the U.S.; India might form similar bilateral relationships with other countries like Japan, Indonesia, Vietnam, and lots of other countries. When a country has 1.4 billion people, a booming economy, and an open society, there’s really very little limit to its potential influence.

I admit that I don’t yet know what all the results of India’s rise will be. But I feel that it has to be something to celebrate — not just because it means hundreds of millions of human beings released from desperate poverty, but because it means a richer world. Economically richer, yes, but also culturally richer, politically more multipolar. It will be a world where power and wealth and global mindshare is no longer monopolized by the powers that carved out empires in the 19th century. If the human race is to flourish on this planet, India’s rise had to happen. So let’s simply welcome it.

"Indian polity revolves around those who believe that India went through single colonization (European) vs those who believe India went through double colonization (Islamic and European)"

*Everything* about Indian politics will make sense if one understands above statement.

I can give a link where 2 from first camp and 2 from second camp debate (in english) ==>

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7dbG4IC7UOM&t=2790s&ab_channel=TIMESNOW

I spent 2-3 weeks per quarter for three years (2012-2015) in India on business ( I worked for a sustainability certification for IT at the time and was engaging Indian purchasers and brands to promote the certification as a way to identify more sustainable hardware). The rate of growth and wealth building was truly astonishing - showing up even between those quarterly visits in astonishing ways! The first time I visited the tech-brand-hub city of Gurgaon a woman was hoeing and a cow was wandering around in a big empty lot near the Dell building. By 9 months or a year later the whole area was crowded with tech brand HQ buildings and a huge mall was crowded with thousands of middle class people with money to spend on Friday afternoons and weekends. The Wipro tech services Bangalore campus was a manicured, sustainably landscaped space where thousands of well dressed young people ate in sparkling food courts during lunch hour. Hyderabad has an astonishing cluster of medical and other businesses, with a brilliant flyover highway making it possible to cross town in no time. (Despite my enjoyment as an outsider of traffic coming to a standstill for local festival parades to go by, it certainly slows down business!) Noida outside Delhi had literally dozens and dozens of residential apartment buildings going up - being built by hand by laborers in a much more labor intensive way than any construction in the US . The scale of rapid growth and increasing prosperity was visible every day - contrary to US perceptions of India as a dusty backwater. There is still immense, visible, intractable poverty, with ragged tents of laborers even in central urban streets and large swathe of the countryside still not fully electrified. But I have an enduring admiration for the grit, determination, cleverness and industry I witnessed in India - and for the creativity and initiative with which individuals pursue "the American dream" of finding a way to make a living, get an education, build a business, have a home. Some of the industrial stuff has yet to reach the Chinese pinnacle of sophistication - but I would never bet against India. Modi on the other hand is a divisive guy and while his government may not be directing the pogroms, they do happen with impunity, just as they did in Gujarat when he was in charge. And even if you view it with no moral judgment (not sure who that would be possible but...), riots and murders breaking out randomly are not good for business continuity