Europe is not ready to be a "third superpower"

For that, it would need to act as a unified entity, defend itself against Russia, and embrace new technology.

During his big trip to China, Emmanuel Macron declared that Europe should become a “third superpower”, with strategic autonomy from the United States. The trip and the declaration sparked a huge controversy in Europe, with some agreeing and others enraged. Macron has continued with this line of rhetoric since returning from his trip.

I’m not in the “enraged” camp. First of all, Macron’s comments were specifically about how Europe should stay out of a U.S.-China conflict over Taiwan. But I never really expected Europe to get directly involved in such a conflict; it’s not one of the EU’s core interests, and Putin is already giving the Europeans all they can handle. Also, this kind of declaration seems pretty typical for a French politician — loudly proclaiming that France is not America’s lapdog has been a staple of the country’s domestic politics since WW2. Macron, facing domestic unrest in the wake of painful pension reforms, is simply reverting to this playbook but subbing in “Europe” for “France”.

In fact, I’ll go farther and say that it would be good for the world if Europe became a third superpower. A multipolar world is inevitable, and having a second pole committed to democracy and human rights, rather than having these notions inextricably associated with American power, would be a good thing. There are also times when Europe is right and the U.S. is wrong, such as the Iraq War. And it would be great for the U.S. — and bad news for Putin — if the transatlantic alliance were more of a partnership of equals.

The thing is, Macron’s dream of Europe as a “third superpower” looks like nothing more than typical French politician guff. The truth is that the region is simply not prepared to become anything resembling a superpower.

Buying off the barbarians

For one thing, Europe is politically disunited, as the uproar over Macron’s trip shows — its constituent states are not quite independent, but the whole is not quite a superstate either. This disunity was on display in the Eurozone financial crisis a decade ago, in which only after years of bitter infighting did the euro states agree on a bailout package and quantitative easing similar to what the U.S. did almost instantly. It has been on display in the Ukraine war, where the EU states have carried out their own uncoordinated approaches toward military and financial support for Ukraine, as well as on sanctions toward Russia. The nation-state is still the level at which key policy decisions are made, and Europe has not yet decided whether it’s a single nation-state or a collection of them.

Europe also appears incapable of keeping its main military threat at bay without massive American assistance. On paper, it looks as if European power should dwarf Russian power; Europe has at least three times Russia’s population and at least ten times Russia’s manufacturing capacity:

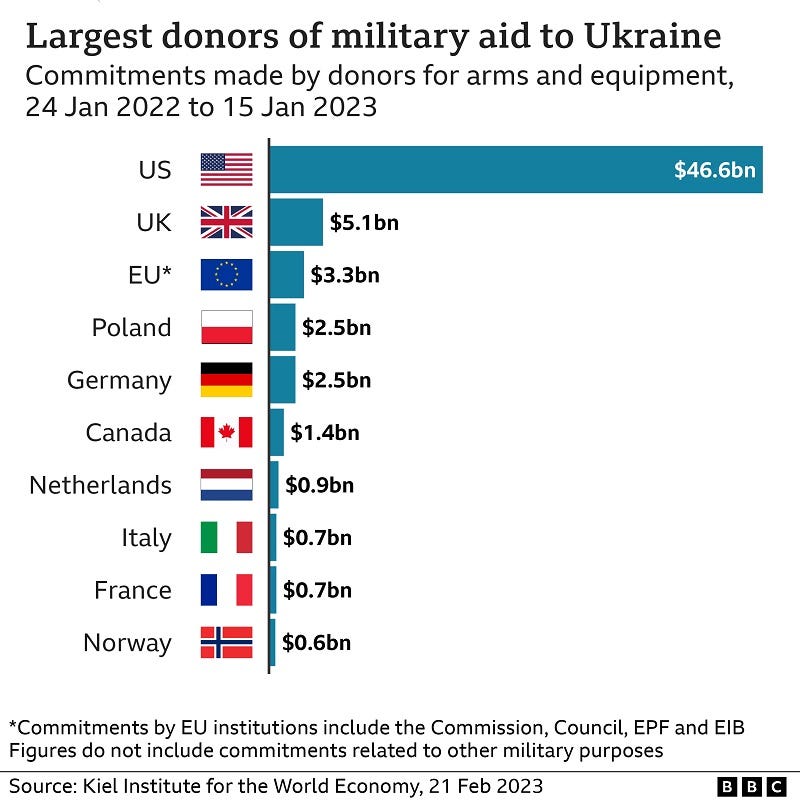

And yet the military aid that has kept Ukraine from being overrun by Putin’s armies has come almost entirely from the United States, not from Europe:

Part of this military feebleness is due to the lack of a unified European military command, which means that NATO — which is dominated by the U.S. — is left to fill the role of “army of Europe”. But part of it is because European countries just don’t spend much on defense. Russia spends over 4% of its GDP on its military, while the core European states of France and Germany spend much less:

Now, these countries have so much bigger of a total GDP than Russia that even with lower percentages being spent, France and Germany’s total spending exceeds Russia’s by 50%. But given the much higher costs in these countries, it’s an open question how much combat power that spending is actually buying. Russia had thousands of main battle tanks before the Ukraine war; France and Germany had fewer than 300 each. Russia had over 3000 multiple rocket launchers; France had 13, and Germany 38. Russia had over 6000 self-propelled artillery pieces; France had 90, and Germany had 121. Between them, France and Germany had fewer than half as many combat aircraft as Russia. And so on, and so forth. Since most of the military assistance to Ukraine has been in the form of hardware rather than cash, it’s little wonder that the U.S. has done all of the heavy lifting here; Europe simply doesn’t have the hardware to give.

Even in terms of total armed forces personnel, all of Europe combined had only about 30% more than Russia before the war.

As long as Europe doesn’t have the ability to hold a weakened, dysfunctional Russia at bay without massive American help, all Macron’s talk of “European sovereignty” will continue to ring hollow. Instead, like China and the Roman Empire both did during past periods of weakness, an independently acting Europe is more likely to try to buy off the Russian barbarians — by paying economic tribute in the form of gas purchases, and by allowing Putin small bits of territorial conquest in the hope that he will eventually be satisfied. This placating strategy was at the core of both Germany’s and France’s approaches before the 2022 invasion of Ukraine, and it would almost certainly be at the core of a European foreign policy strategy that cast the United States aside.

But increasingly, Europe’s weakness isn’t just military; it’s economic and technological. A region that once dominated the global economy is now falling behind in almost every important area of industry, and in economic importance as a whole.

Ming dynasty Europe?

It’s impossible not to notice that Europe is being economically eclipsed. The EU’s GDP was equal to America’s in the early 1980s, but since then it has grown considerably more slowly. As for China, its economy eclipsed Europe’s in size as of 2020.

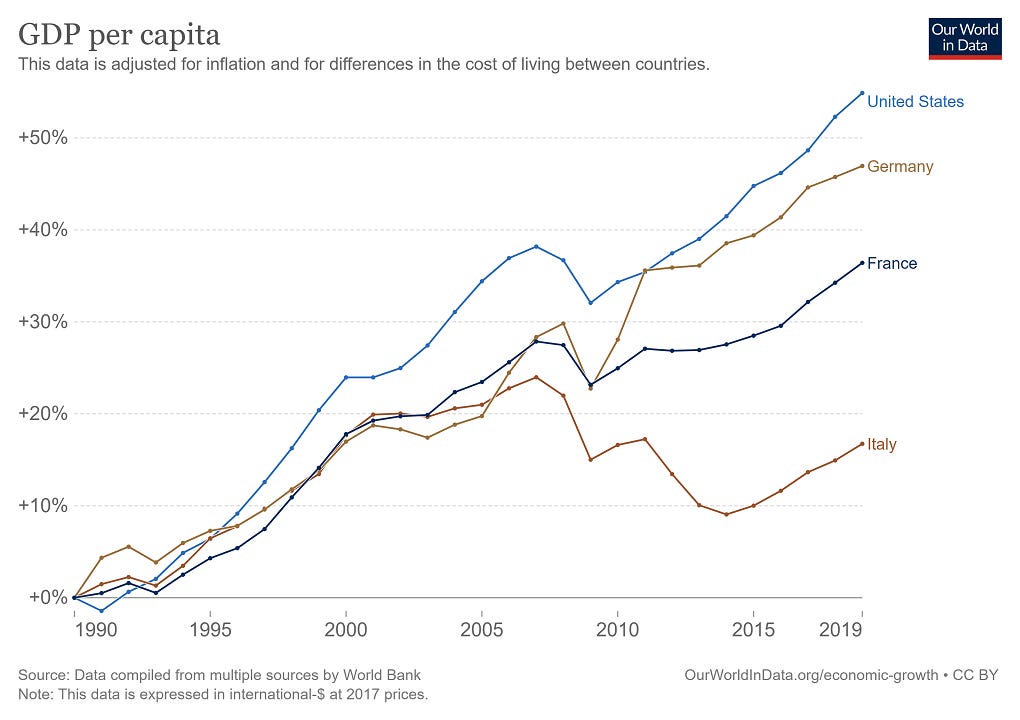

Much of Europe’s relative decline is demographic, even though Europe now lets in tons of immigrants and has a total fertility rate only slightly lower than the U.S. A more worrying issue is slow growth in per capita output. Though East Europe has grown quickly since its communist days, and Germany has mostly kept pace, France and Italy have seen living standards grow much more slowly than those in the U.S.

But even more disturbing is the way Europe’s core economies have seemingly turned their backs on the technologies of the future. Despite the strength of East Europe and Ireland in the software industry, and despite little competition from China, Europe as a whole has failed to become a software supercluster like the U.S. has. Instead of an economic opportunity to be exploited, Europe has treated the internet as a problem to be regulated.

European countries also produce very little of the infrastructure and equipment that forms the backbone of the global internet. As Jonathan Hillman writes in The Digital Silk Road, Europe has instead opted for a strategy of trying to control standards-setting bodies; instead of producing, it tries to make rules about what others should produce.

On the rapidly emerging technology of AI, Europe has been even worse. Faced with the incredibly powerful and versatile new technology of large language models, Italy simply banned ChatGPT, and France has threatened to do the same. Despite producing lots of top-tier AI researchers, Europe has little presence in the AI industry. As with the internet, Europe has used a regulation-first approach to AI.

But what about hardware industries, where Europe has traditionally been stronger than in software? Europe used to export lots of cars to China, but in the last few years the balance has shifted abruptly:

Much of this is due to Europe’s lagging position in electric vehicles, as the world shifts away from internal combustion engines. Europe buys plenty of EVs, but it doesn’t produce what it buys:

In wide-body aircraft, one of Europe’s traditional manufacturing strengths, Macron agreed to double Airbus’s production in China on his recent trip there. It seems likely that China will use this as an opportunity to appropriate Airbus’ technology and eventually outcompete the European company — as it has been trying to do to the U.S., and as it did to Germany’s Siemens in high-speed rail technology.

Examples such as this abound. Germany sold its robotics manufacturing champion Kuka Robotics to Chinese buyers, making it more likely that Germany’s products in that industry will shortly be outcompeted by Chinese rivals in relatively short order. Whether it’s using China as a cheap production base or selling core technology to Chinese companies, France and Germany seem to consistently choose quick cash over maintaining their long-term technological lead in advanced manufacturing.

Of course, all this is on top of boneheaded policies like Germany’s decision to close its nuclear plants in the middle of an energy crisis.

In sum, Europe appears to be turning its back on the technologies of the future, viewing them either as threats to be regulated away, or as consumption goods to be imported from China. If you want to be a superpower, this is not the kind of thing you do. Mastery of cutting-edge technology leads to both economic and military power; the EU will not be able to substitute regulatory power or moral power in their place.

There’s a parable we tell ourselves about the Ming and Qing dynasties that ruled China from 1368 to 1911. The conventional wisdom is that during this period, China turned its back on the outside world and on new technologies, choosing instead to look inward and cultivate a tranquil, harmonious, static society. The Ming burned their oceangoing ships in the 1500s and sealed the country off from most trade. In 1793, the Qing emperor declared to a British trade mission that “Our Celestial Empire [has] no need to import the manufactures of outside barbarians.” That isolationism was brought to an abrupt end when China’s technological backwardness and military weakness made it incapable of resisting foreign aggression in the 1800s, leading to the “century of humiliation”.

That is the story we like to tell, and perhaps there’s some truth in it. But even if it’s just a fable, Europe seems in danger of making that sort of mistake in the modern day. It risks becoming a backward but tranquil society, smug in its relatively high quality of life, refusing to engage with what Macron calls “crises that are not ours”. That strategy might work for a while, as France and Germany buy off the Russian barbarians and make a quick buck selling a century of accumulated technological leadership to the Chinese at bargain-basement prices. But in the long run, a decline into weakness, irrelevance, and backwardness will not work out for Europe any better in the 21st century than it did for China in the 19th. The consequence won’t just be the failure of Macron’s ridiculous dreams of being a “third superpower”. Someday someone will show up on Europe’s doorstep who can’t easily be bought off, and the era of harmonious stasis will come to a nasty end.

I agree with the sentiment of this but the Ming/Qing China comparison is way off base. Those are a story of overly strong central governments mandating stasis and isolation. Europe is fragmented with the EU subordinate to the member states. Many of the issues raised in this piece are symptomatic of that, e.g. German gas policy or French technology transfer to China. These make sense for the individual member states but not the EU as a whole. This fragmentation also precludes long-term stasis. The EU isn't able to force Denmark to burn the Maersk fleet nor get all 27 states to close their borders. Some kind of local-optimum temporary stasis is all you get.

"Someday someone will show up on Europe’s doorstep who can’t easily be bought off, and the era of harmonious stasis will come to a nasty end." This is a prediction of something that already happened - Russia/Ukraine. The process of military renewal has already begun. Yes, the EU will probably not be a 'third superpower'. Even if it re-arms and re-industrialises so will other areas of the world at as great a rate.

Europe won't be a superpower, nor will it's individual states be superpowers again. However, greater military power is very likely (and will have unpredictable effects in the region). As for technology, Europe has not meaningfully fallen behind yet, and re-establishing industries in already advanced economies may prove to be easier than establishing new industry in developing economies. Under the current system of trade most industry in Europe simply doesn't make sense no matter EU or state policies. But if that system is upended by China/USA conflict then that calculation would change in an instant.

A shame the UK stepped away from the project, we could at times push the French and German axis forward on some matters.