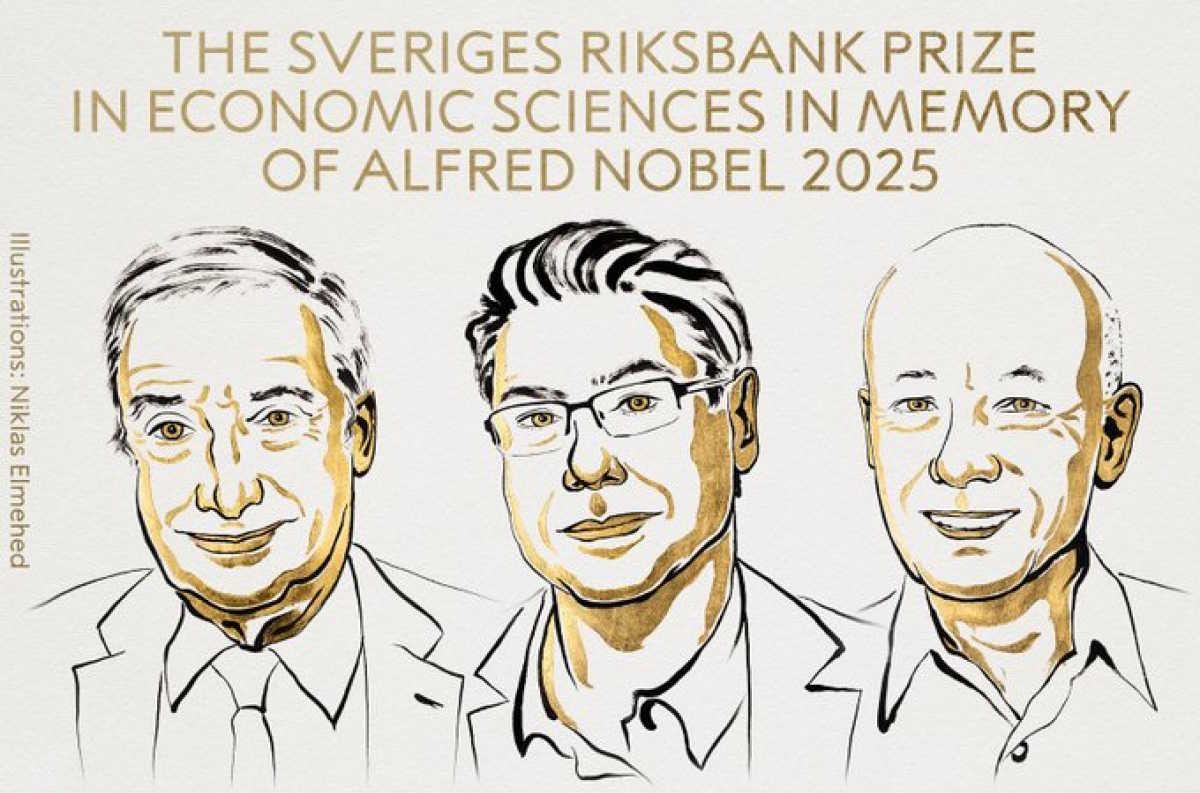

A Nobel for thinking about long-term growth

Aghion, Howitt, and Mokyr tackled the biggest question of all.

Well, it’s time for my annual Economics Nobel post! If you like, you can also check out my posts for 2024, 2023, 2022, and 2021.

Other than the tired old question of whether the Econ Nobel is a “real” Nobel prize,1 there are basically three things to talk about in these posts:

The research that got the prize

What the prize says about the economics profession

What the prize says about politics and policy in the wider world

So first let’s briefly talk about the research. This year’s prize went to Joel Mokyr, for writing about culture and growth, and Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt, for making models of technological innovation. For good summaries of what this prize is all about, see:

The Nobel committee’s own explanation

Alex Tabarrok’s post, mostly about Aghion and Howitt

Kevin Bryan’s post about both winners

Anton Howes’ post about Mokyr

I’m personally much more familiar with Aghion and Howitt’s work, so let’s start with that. The main idea they won the prize for is a model of how competition drives innovation, which they published in 1992.

The basic idea of this model is that technologies become obsolete as they’re replaced by better technologies. If you’re in academia, this might not be a problem, because your goal is to publish papers. But if you’re in a company that’s trying to turn a profit, the notion of your discovery being superseded should worry you. Suppose you spend a bunch of money and hire a bunch of researchers and invent a cool new product, only to see it superseded a year later by something even better. That’s how Digital Equipment Corporation must have felt when their cool new “minicomputers” were quickly made obsolete by the advent of the personal computer. It’s Joseph Schumpeter’s “creative destruction” at work.

In Aghion and Howitt’s model, this creative destruction deters companies from investing in research.2 It provides a natural brake on the pace of technological innovation, and limits how fast the economy can grow.

In 2005, Aghion and Howitt published an important update to this theory, co-authored with Nick Bloom, Richard Blundell, and Rachel Griffith. The new theory deals with the effect of competition on the rate of innovation. If a market is very competitive, the Aghion and Howitt (1992) theory dominates, and innovation is relatively low. If the market is very uncompetitive, it’s also less innovative, because a monopolist doesn’t feel threatened enough to innovate. But if the market is simply somewhat competitive, then companies will innovate a lot, because whoever wins the competition will get tons of profit from being a temporary monopoly.

Innovation is therefore maximized when companies are “neck and neck”. It’s easy to look at the incredibly expensive AI competition going on right now, and see this kind of “neck and neck” effect at work.

This is all pretty standard macro theory stuff — it imagines a pretty simple economy with just enough complexity to explain the idea that the authors want to think about, and works through the mathematical implications of that theory. And in fact it’s a bit easier to test than many macro theories, because it isn’t actually pure macro — the models’ primary implication is about how individual companies behave, which lets you get some causal evidence.3 Some causal evidence supports the “inverted U” of Aghion et al. (2005), while other studies fail to find it.

What’s harder to think about is how to apply these models. As Lina Khan and other modern antitrust advocates have discovered, there’s not really a big dial labeled “amount of competition in the economy” that you can easily turn. Someday we may be able to do that, but right now, Aghion and Howitt’s most famous theories remain largely descriptive rather than prescriptive.

As a side note, Aghion is one of my favorite economists, and I know his research fairly well (Howitt’s less so, sadly). And these aren’t actually my favorite papers of his! So let me mention some others that I think are important.

He has a 2017 paper with Benjamin Jones and Charles Jones that provides a good way of thinking about how AI will affect economic growth — and pretty prescient, considering it was written five years before ChatGPT even came out. Basically the idea is that AI is still constrained by bottlenecks, and that as AI handles more and more, the bottlenecks become more and more important. This is why Tyler Cowen predicts that AI won’t supercharge growth as much as optimists expect.

Aghion also has a 2018 paper with Bergeaud, Lequien and Melitz, looking at the effects of exports on innovation. As someone who has advocated for export subsidies as a way to boost productivity, I often find myself going back to this paper. The upshot is that top companies become more innovative when they compete (and win) in world markets, but less-competent companies become less innovative due to the creative-destruction effect.

Aghion also isn’t just a theorist; he does important empirical work as well. Aghion et al. (2015) found that China’s industrial policy often increased productivity by boosting competition4 — obviously a topic I’m very interested in. His 2023 paper with Blundell and Van Reenen found that regulation has a real and negative effect on businesses in France (though perhaps not as big an effect as one might expect).

And perhaps most relevantly, Aghion, Antonin, Bunel and Jaravel did a literature review in 2022 on the relationship between automation and jobs. They find that at both the company level and the industry level, automation actually increases jobs, probably by growing the overall size of the market:

In this article, we survey the recent literature and discuss two contrasting views on the impacts of automation on labor demand. A first view predicts that firms that automate reduce employment, even if this may ultimately result in job creations taking advantage of the lower equilibrium wage induced by job destructions. A second approach emphasizes the market size and business stealing effects of automation. Automating firms become more productive, which enables them to lower their quality-adjusted prices, and therefore to increase the demand for their products. The resulting increase in scale translates into higher employment by automating firms, potentially at the expense of their competitors through business stealing. Drawing from our empirical work on French firm-level data and a growing literature covering multiple countries, we provide empirical support for this second view: automation has a positive effect on labor demand at the firm level, which remains positive at the industry level as it is not fully offset by business stealing effects. [emphasis mine]

This contradicts the dire predictions of researchers like Daron Acemoglu who believe that automation is a job-killer. It was written before generative AI came out, so this result could change, but it’s highly encouraging.

Anyway, those are my favorite Aghion papers, and I kind of wish more of them would have been cited in his Nobel, but in general I’m very glad he won the prize. He’s really one of the best researchers we have on the topic of innovation — a key voice guiding us through our strange new era of rapid technological change.

Anyway, on to Mokyr. Mokyr’s key work, especially his book A Culture of Growth, is very different than Aghion and Howitt’s. It’s basically a narrative history of the scientific advances that led to the Industrial Revolution. I’ve never read the book, mostly because I’m inherently skeptical of cultural explanations of growth, but I guess now I have to read it.

Mokyr’s explanation of why the Industrial Revolution happened in Early Modern Europe, as opposed to in China or somewhere else, isn’t completely cultural. Part of his hypothesis is technological — he thinks the printing press allowed scientists and engineers to more easily exchange ideas and build on each other’s innovations. This is actually somewhat testable — for example, Dittmar (2011) showed that the spread of the printing press predicted future economic growth.

Mokyr also cites political factors — in particular, Europe’s fragmentation, which allowed scientists and inventors to shop around for a country that would support them. It might be possible to test this too, using natural geographic factors (which tend to separate regions into multiple countries) to predict where growth would eventually happen.

But Mokyr’s most famous idea — and the one that he put in the title of his book — is that Europe’s top scientists and thinkers had a special culture that allowed them to kick-start economic growth. Basically, Mokyr argues that they believed in the idea of scientific progress — the idea that science and technology are basically good for humanity, and that they naturally build up and improve over time. This attitude, he thinks, was key to Europe’s take-off — and, eventually, to the whole human race’s ability to escape poverty.

It annoys me a bit that this type of work won a Nobel prize. This is not because I disagree with the idea — in fact, I think it’s probably quite right, and despite never having read Mokyr at all, I’ve been writing for years that we need similar attitudes in the modern world:

I love the general outline of Mokyr’s ideas, and I expect I’ll find them very reasonable. But I don’t think the Econ Nobel should be about ideas that simply sound legit — even if I’d personally make policy based on those ideas.

In previous years, the prize had been trending toward greater recognition of empirical economics and applied theory — basically, it had been rewarding economists who made econ more of a science. An award for narrative history and untestable theories about culture takes us in the exact opposite direction.

In fact, I spent most of my Nobel post last year complaining about Acemoglu and Robinson doing something similar, with their theory of institutions and development:

But at least Acemoglu and Robinson tried to test their theory empirically! Yes, the tests aren’t that reliable, but at least there’s still the idea that some sort of empirical, testable science is being done. Mokyr tries to quantify some of the cultural elements he’s talking about, but he doesn’t actually try to test his theories against data. It’s not a bad or worthless exercise, but it’s not scientific at all.

The effect on the economics profession may not have been foremost in the committee’s mind, however. Instead, they may have been thinking about the anti-growth turn in Western culture. Under Trump, America is embracing antivax lunacy and ignoring the power and promise of electric technology, while regular Americans are terrified of AI. Meanwhile, much of Europe is embracing degrowth ideology and shunning air conditioning, while over-regulating information technology.

The West, in other words, may be losing the very secret sauce that powered its rise. We desperately need Mokyr’s culture of growth — the belief in the power of innovation to help regular human beings, and the conviction that progress is cumulative. The Nobel committee may be sending a message to Western civilization to break out of the high-level equilibrium trap into which we may have fallen.

That is an important and timely message indeed.

It is.

It’s actually only one of two deterrents. The other deterrent is that when the pace of research is really fast, companies know they’ll have to overpay for researchers down the line just to stay in the race, which will reduce their future profits. That sounds hokey until you remember that Meta is now paying AI researchers $250M salaries.

It’s very difficult to figure out cause an effect when you’re dealing with one entire economy, but a lot easier when you have lots of different companies you can look at.

If you accept the “inverted U” theory of competition and innovation, this result implies that before the industrial policies, China’s industries were too dominated by SOEs or other uncompetitive quasi-monopolies. So industrial policy might be a good antitrust tool!

We have a Luddite President. His brain works on dystonia. On one hand, he is pushing AI, on the other, he is pushing coal as a power source. He works on peace in the Middle East while making war on Democrats.

I completely agree that the country's attitude after President Kennedy challenged us to go to the moon is vastly different. We used to be a “can-do” nation. We had inventors working in their garages all over America. Necessity is the mother of invention. All that has disappeared.

We don’t seem to have the curiosity anymore. Perhaps I exaggerate, but from all appearances, the nation is exhausted, and the lack of will to do the hard and difficult is obvious. I could list 101 things that we would have worked on decades ago that both parties would have worked on. A Congress that solved problems.

When I look at America, I see something that more resembles England after WWII.

I really like the model that technologies become obsolete as they’re replaced by better technologies.

Materials science and engineering and Chemistry are underrated sciences, and we see technological substitutions happen all the time!

In the 1870s, petroleum from Russian Azerbaijan and Pennsylvania in America largely replaced palm oil from Nigeria as an industrial lubriciant.

https://open.substack.com/pub/yawboadu/p/how-a-corporation-became-a-colony?utm_source=share&utm_medium=android&r=garki

Or when Peruvian Guano or Chilean nitrates got replaced with synthetic fertilizer from German Scientists.

Or now with Chinese synthetic diamonds killing De Beer's diamond cartel.

https://open.substack.com/pub/yawboadu/p/guns-germs-and-cobalt-q-and-a-9-insights?utm_source=share&utm_medium=android&r=garki

Technological substitution is the biggest killer of resource nationalism.