The elemental foe

Lifting humanity out of poverty is Job #1.

I remember a particular scene out of a book that terrified me when I was seven years old. During an argument, some minor character talks about having been to Calcutta and having witnessed the desperate poverty there. He describes seeing beggars on the street, starving, covered in sores. That mental image stuck in my mind for weeks. Even as a child, having never myself known absolute poverty, I had an elemental terror of it.

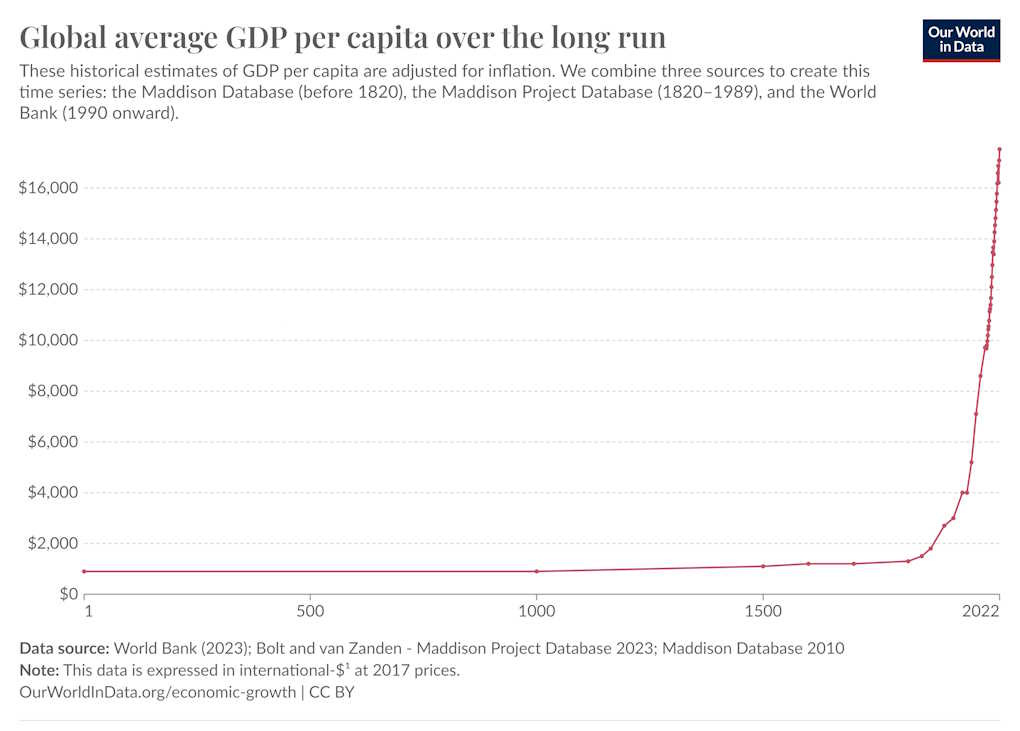

To ask why some societies in the world are still poor is the wrong question. Poverty is the default condition, not just of humanity but of the entire Universe. If humanity simply doesn’t build anything — farms, granaries, houses, water treatment systems, electric power stations — we will exist at the level of wild animals. This is simply physics.

Look at pictures of the other planets in the solar system — sterile desolate rocks and poison gases baked by radiation. That is the natural state of most planets. Then look at animal existence in the wild places of the world — a constant desperate struggle for survival, where populations are kept in equilibrium only by starvation and predation. That is the natural state of most life. Then look at how humans lived for the vast majority of our history — indigent subsistence farmers forever skating on the rim of famine. That is the natural state of preindustrial humanity.

When we spin fantasies of our collective past, we write about kings and princesses, because they’re the only ones who lived lives we could even remotely relate to today. Even then, the comparison is only approximate — the mightiest emperor of yesteryear had plenty to eat, but lacked antibiotics, vaccines, flush toilets, or air conditioning.

Even now, having escaped true poverty, you walk through your days with no consciousness of how closely it stalks behind you. Remember the last time you had to go an extra hour without eating? Remember the gnawing feeling in the pit of your stomach, the red fog that seemed to settle over your brain? You are always just a few hours away from that. You will never outrun it. Humanity as a whole is only a few days or weeks away; if the elaborate and fantastically expensive food supply and distribution system we’ve built were to suffer an interruption, we would be reduced to the level of starving wild animals in short order.

In the developed societies almost all of us manage to stay a few steps out of reach of that monster for our entire lives, and this fact is the wonder of the world. The artifice we have built to keep it at bay — vast farms blanketing whole continents and tended by fantastic machines, sprawling landscapes of ersatz caves to keep us sheltered from the elements, endless roads and rails, an empire of warehouses and supermarkets and pharmacies and just-in-time logistics — is the only meaningful thing that has ever been built within the orbit of our sun in billions of years.

It is industrial modernity — our single weapon against the elemental foe. It took centuries of blood and sweat to build, centuries of sacrifice by our sturdiest workers, our most brilliant inventors, and our most visionary leaders. And it is fantastically complex, far beyond the ability of even the most brilliant individual to understand in full; only collectively, at the level of society, do we shore up its fragile walls and keep it from collapse every day.

When smug intellectuals sneer at “economic growth” or “GDP”, they are denouncing the very walls of the fortress that has allowed them to live more than an animal existence. Safe within its sheltering bastions, they are free to indulge in the extravagance of pretending that the foe isn’t lurking right outside. They revel in the luxury of their material security by staging mock revolutions over differences in social status and relative wealth among the elite. With their bellies full of industrially grown sugars, they wander through pleasant fantasies of an imagined past — pastel-colored worlds filled with noble savages, happy indolent peasants, and glossy 1950s advertisements. Sometimes they imagine they could move to one of those fantasy worlds.

As shallow as all that sounds, it’s precisely to allow the luxury of shallowness that humanity struggled so long and hard. Yet we can never afford for luxury to become complacency, because the foe has not been defeated. Ageless and sleepless, it crouches outside, scratching and gnawing at the walls, waiting for the fat and happy people inside to forget about its existence — waiting for them to stop maintaining the fortress of industrial modernity.

Thus, there must always be some of us who remember the presence of the foe. To those of us who remember falls the task of restraining the pleasant fantasies — of preventing them from spilling over from indulgent imagination into real policy. To us falls the tiresome task of reminding the world that degrowth would return us to a more savage, cutthroat existence. It is our thankless job to remind the world that GDP is much more than just a line on a chart — and at the same time, to draw this line on this chart again and again, ad infinitum.

And to us also falls the task of reminding the world that growth must be sustainable. If we burn the walls of our fortress to throw a party in the moment, there will be nothing left to protect our descendants, and the foe will devour them. It is tempting to believe that manmade climate change is not real, that natural habitats can be razed without consequence, and that the world’s waters represent an infinite safe dumping ground for pollution. These are all just more unaffordable daydreams.

Part of this task is to remind the world of the importance of technological progress. Without newer and more sustainable sources of energy and materials, our choice would be between degrowth and environmental destruction. Technology built industrial modernity, and technology sustains it, and only technology can extend it into the indefinite future.

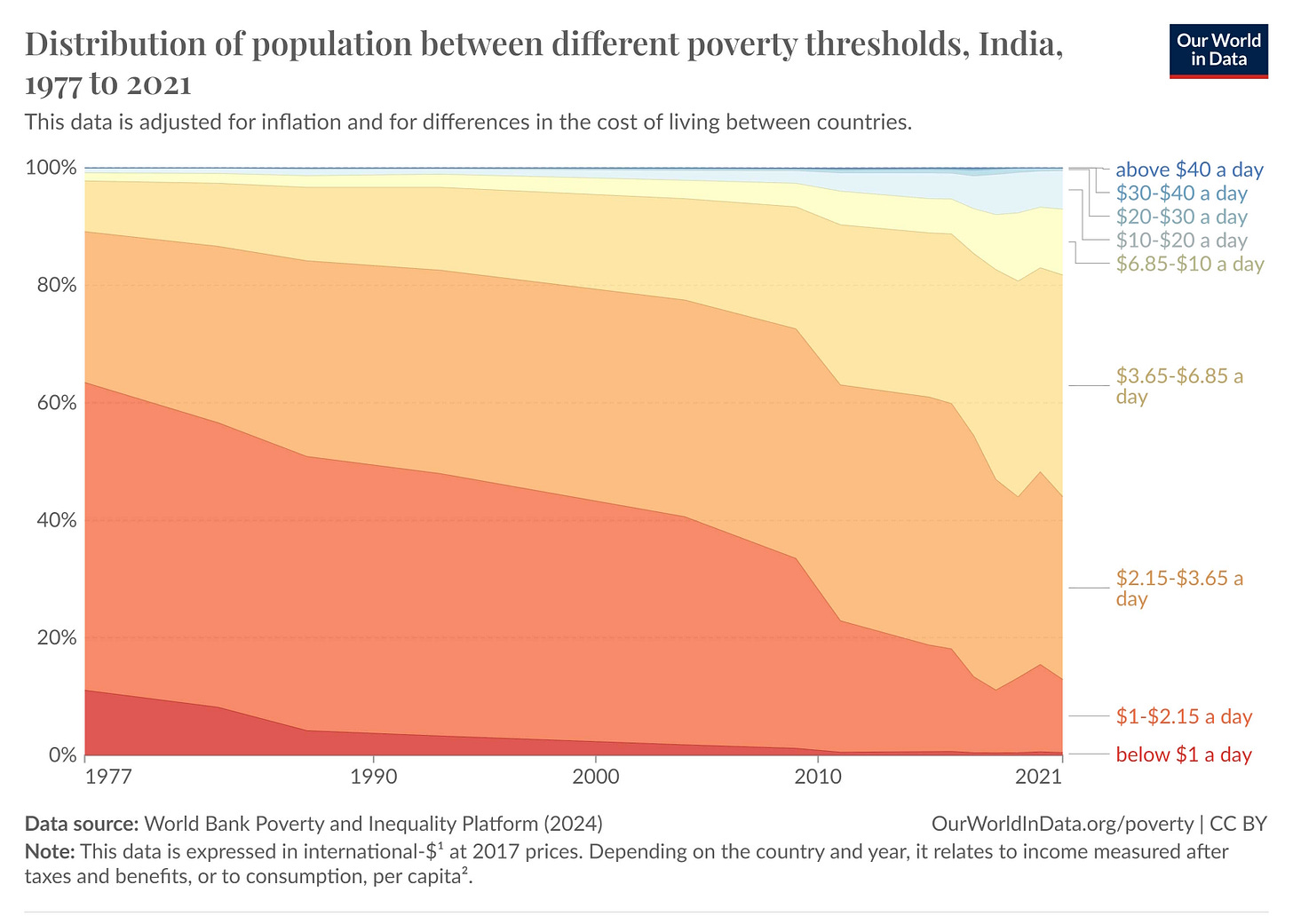

But most of all, it falls to us to extend the fortress’ protection to every human on the planet. As you read these words, there are still billions of humans living outside the sheltering walls of industrial modernity — still grappling hand to hand with the foe. Less than half of humanity lives on more than $10 a day. Almost two billion live on less than $3.65. Two billion lack access to safely managed drinking water. Every day, 190 million people go hungry in India alone.

No redistribution of resources from Europe and America to India and Africa will fix this. The wealth of the world is not a fixed lump of treasure to be plundered; that is simply another daydream. Our true wealth is not gold and paintings lying in vaults in rich men’s mansions; it is the system of industrial production and logistics that is built and rebuilt and maintained every day by billions of human hands. Foreign aid is helpful, but it cannot substitute for economic development. Industrial modernity must be built out where it does not already exist.

I will be the first to tell you about the drawbacks and dangers of China’s rise as a world power — about its totalitarian society, and the danger that its pride and ambition will plunge the world into a devastating war. I will be the first to tell you that to think that wealth would bring China freedom was wishful thinking. And I will be the first to tell you that China’s entry into the global trading system could have been much better managed — that its undervalued currency and disrespect for the global environment were problems that could have been ameliorated with proper foresight.

And yet, when I look at China’s achievement in pulling over a billion people out of the jaws of poverty, it’s hard to say the tradeoff wasn’t worth it. Before the 1980s, most Chinese people lived in desperate, grinding poverty — not just because of the insanity of Maoism, but because poverty was China’s natural state for its entire history, just as it is the natural state of every preindustrial society. Xi Jinping may have grown up in a cave because of the Cultural Revolution, but the condition of the average Chinese peasant for most of recorded history was not much better.

China’s rise to wealth, engineered by Deng Xiaoping and his successors, and carried out by untold millions of Chinese entrepreneurs and workers, was among the greatest blows humanity ever struck against the foe — rivaled only by the Industrial Revolution itself. Nearly a fifth of the entire species was elevated to something approximating a materially comfortable existence. Even acknowledging all the drawbacks, it’s difficult to imagine a better world in 2024 where that didn’t happen.

And now, incredibly, humanity might be repeating that feat just a couple of decades later. India, now the world’s largest country, is growing rapidly — not as rapidly as China did, but fast enough to have already brought most of its citizens out of the most extreme poverty.

If India can complete this repeat of China’s accomplishment, it will leave only Africa, and a few small areas of the globe, outside of the sustaining arms of industrial modernity.

It is impossible to point this out on social media without someone attempting to qualify the statement with criticism of Narendra Modi’s government. But while criticism of leaders is good and welcome, it is sheer inhumanity — the most destructive of rich-world daydreams — to imagine that these flaws make India’s rise to riches a bad thing on balance. However bad you believe Modi to be, he’s less bad than the CCP — and China’s enrichment was still one of the best things that ever happened to the human race. Modi is just a person, and countries are bigger than people.

Lifting another billion humans out of the jaws of poverty is an overriding moral imperative. And so the United States, Europe, Japan, Korea, and other rich countries should invest as much as economically feasible in India. They should open their markets to any and all Indian goods, to whatever degree domestic politics will allow. And they should offer whatever development assistance they can — in particular, the building and financing of high-quality infrastructure. All this should be done whether it’s Narendra Modi or — as looks more likely after the recent elections — someone else who leads the country.

Obviously all of this is also true of Africa, although only a few African countries are ready to receive large amounts of foreign investment at the moment. But policies to keep rich-world markets open to African goods, and to encourage more investment in the continent, are moral imperatives — and will ultimately prove even more important than any foreign aid.

If you want to understand the principles that underlie my political leanings, this is the key. Humanity is at war — a war so old, so terrible, and so all-consuming that even World War 3 would be a minor skirmish in comparison. Whether or not we remember it, we are always on death ground. But our intelligence has given us an opportunity not afforded to other animals — the chance to conceive of our species as a single team, fighting not individually but as an army united against the implacable, elemental foe of poverty and desolation.

It is our highest task to push that foe ever backward, to build out the fortress of industrial modernity, to reclaim the Earth for the safety and comfort of beings that think and feel. The Earth, and eventually, all the other places as well.

I've read your stuff for a long time, Noah. And, writing for a living myself, I tend toward that worst bias of regularly thinking I'm the best writer in the room.

So i am very sincere when i say: This? This is some of the best stuff you've ever done. Kudos!

I loved the part about " With their bellies full of industrially grown sugars, they wander through pleasant fantasies of an imagined past — pastel-colored worlds filled with noble savages, happy indolent peasants, and glossy 1950s advertisements"

Fantasies of an imagined past are pretty ripe in African countries unfortunately, partially due to poverty. Even though some racists will say nonsense like "Africa didn't have civilization", which is patently false. The opposite is when people glorify pre-industrial Kingdoms like the Mali Empire.

While it's cool to know who Mansa Musa is, at the end of the day, if we could go back in time, the Mali Kingdom was hellish by modern standards. Mansa Musa, the supposedly richest man who ever lived, died around age 40. Many of the Mansas (Emperors) of the Mali Empire died young by sleeping sickness, like the tsetse fly. The country was a slave state, and despite the Mosques and Islamic centers of learning, the only people who were literate according to the Arab Chroniclers were the elite, while most Malians were illiterate.

We shouldn't glorify the past and we should praise technological progress because poverty is the norm, not wealth.

Below I wrote about the West African Kingdoms if anyone is interested!

https://yawboadu.substack.com/p/the-economic-and-geopolitical-history-26c