A Nobel for the story of women in the workforce

How Claudia Goldin brought all the threads together.

The 2023 Econ Nobel went to Claudia Goldin for her work on women’s labor market outcomes. I can’t say I’m particularly surprised to see Goldin get the nod, here. Economists generally recognize Goldin as one of the key pioneers of the “credibility revolution” in empirical economics.

The main thing you have to understand about the Econ Nobel (or, if you prefer, the Bank of Sweden Prize in Memory of Alfred Nobel) is that it’s typically a methods prize; instead of specific discoveries, like in chemistry or medicine, the Econ Nobel is typically awarded to researchers who invent new ways of making discoveries. In recent years, the prize has been awarded more and more to researchers whose primary focus is empirical analysis rather than pure theory.

This largely just reflects the direction of the overall field. Over the past three decades the econ profession has shifted in a decidedly empirical direction, relative to the theory-heavy stuff that prevailed in the 70s and 80s. A big part of that shift has been something called the “credibility revolution” — a movement toward using natural experiments to test simple hypotheses instead of trying to fit the data to complicated theories. In other words, econ is getting more scientific, and it’s doing it in a way that expands the capabilities of science as a whole, because it’s finding new ways to do science on things that can’t be controlled in a lab. That’s pretty cool.

Anyway, the prize in 2021 went to Card, Angrist, and Imbens, three pioneers of the credibility revolution. Goldin was an obvious choice for another prize in the same vein. A number of her key papers, including her famous 2002 paper with Lawrence Katz on the effects of birth control technology on women’s careers, used and improved the natural experiment technique.

To see how this works, let’s consider that paper, which is entitled “The Power of the Pill: Oral Contraceptives and Women's Career and Marriage Decisions”. In general, if you see a correlation between A) increased birth control use, and B) women getting more education and getting married later, you might wonder which way the causation ran. Maybe women started using birth control because of feminist cultural values, and started getting more education and getting married later for the same reasons? Maybe education would make women want to use birth control more? How do we know that adoption of a technological innovation led to social changes, rather than vice versa?

Goldin and Katz figured out how to identify which way the causation ran. They looked at state-level differences in laws that made it easier or harder for women to get the new birth control pill after the technology came out. This allowed the economists to figure out that the impact of the new invention was crucially important.

I sometimes jokingly refer to myself as a “technological determinist”, and this kind of thing is exactly why. Of course I recognize that social movements and cultural factors are important. But I think there’s a tendency in our society to attribute everything to culture and activism, ignoring the fact that technology sets the boundaries of what cultures and movements can accomplish. Goldin and Katz’ paper on the birth control pill is an important reminder of the indispensable power of technological innovation.

But in any case, back to Goldin’s Nobel. It would be wrong to see this award as purely a sequel to the 2021 prize, because Goldin did a lot more than just analyzing natural experiments. Her real strength lay in weaving together a wide variety of theories and facts to create a coherent story about an important phenomenon — the changing role of women in the workforce.

If you want an overview of how Goldin wove together these disparate threads, I recommend this post by Alice Evans:

I also recommend the interview Goldin did with Danielle Kurtzleben, as well as her Conversations with Tyler podcast interview with Tyler Cowen.

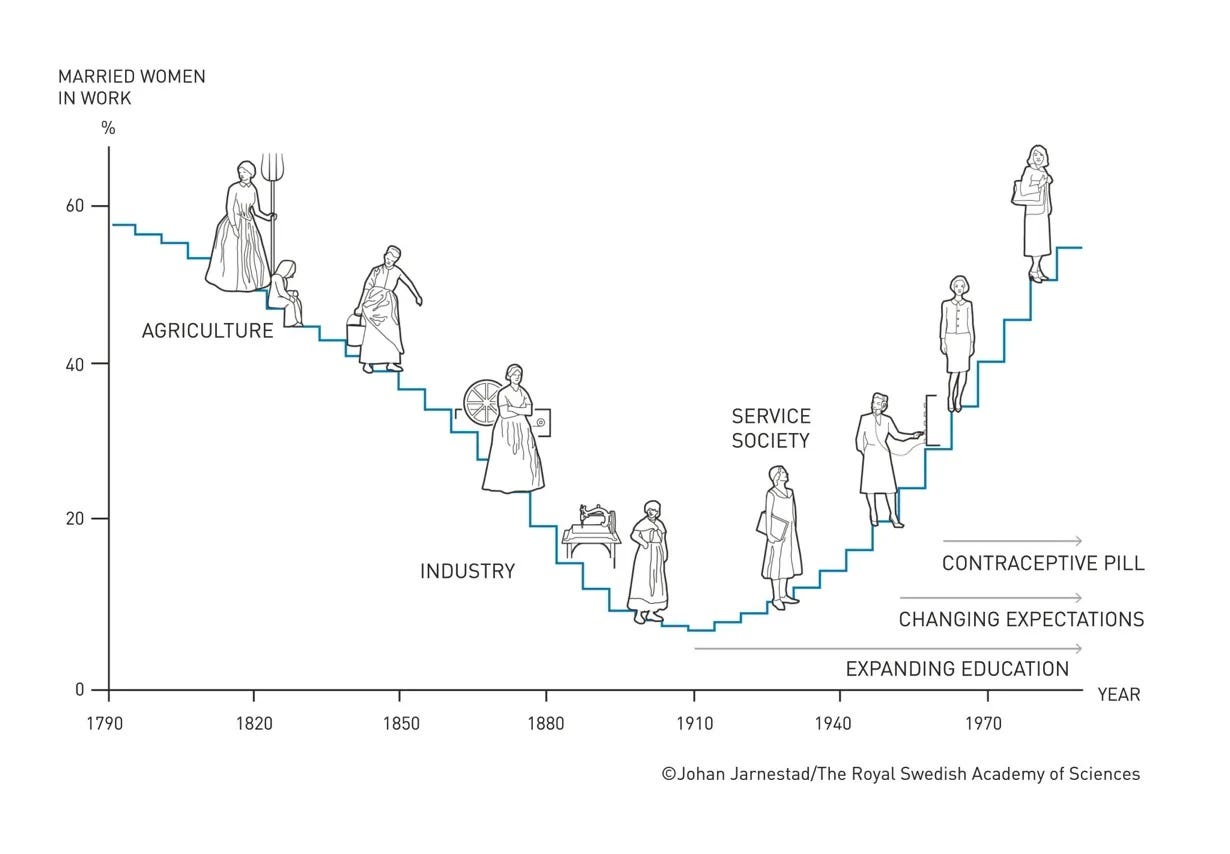

What really stands out here is how broad and eclectic Goldin’s methodology was. She considers theories of female workers as rational decision-makers responding to market demand, but she also considers cultural norms and politics and the spread of ideas. She uses natural experiments, survey research, and economic history. She created whole new data sets, uncovering trends in women’s employment back to the 19th century. This was what allowed her to figure out that women haven’t recently entered the workforce for the first time, but re-entered it. Here’s a helpful infographic from the Nobel folks:

This sort of integrated, eclectic approach is important because the phenomenon of women’s changing role in the workforce is a highly complex one, with a lot of moving parts. There’s the impact of broad “structural” shifts in the economy — the change from agriculture to manufacturing to service industries. There are policy changes like expanded education that affect women’s opportunities in the workplace, and there technological innovations like the birth control pill and home appliances that affect the tradeoff between work and family life. There are social movements like feminism and political changes like anti-discrimination law. All of these things happen at the same time, and they all interact.

If there’s a simple story that emerges from Goldin’s body of work, it’s that the main thing that affects women’s economic situation is the tradeoff between the workplace and the family. If the economy is one that forces people to choose one or the other, it’s going to be harder for women to work. The industrial age, when working meant long hours in a factory far away from home, housework was a huge chore, family planning was difficult, education was rare, and families passed on traditions of separated gender roles, made it uniquely difficult for women to go out and earn a living in the marketplace. The new service economy, with all the new technological and cultural innovations of the past century, has made it more possible to take care of a family and still go out and have a job. And thus it is that we live in a much more gender-equal age.

But “more gender-equal” doesn’t mean that inequality has been conquered. One of Goldin’s most famous papers, a 2010 study with Katz and Marianne Bertrand, found that women still face somewhat of a choice between child-rearing and careers. Following the careers of MBAs from a top business school, they found that motherhood was correlated with interrupted careers and shorter working hours — factors that statistically explain most of the remaining gender wage gap. The key is that women are the “on-call parent” within most families, which requires them to have more flexible work arrangements — and thus less high-powered careers.

When I look at this research result, it immediately suggests two ways to close the remaining gender wage gap. The first is a preference shift to get men to care more about childcare. As Goldin found, those cultural shifts can matter a lot. But being a technological determinist, I’m more optimistic about a new innovation: remote work.

In a 2014 paper, Goldin writes that the key to advancing gender equality is to make work more flexible:

But what must the "last" chapter contain for there to be equality in the labor market? The answer may come as a surprise. The solution does not (necessarily) have to involve government intervention and it need not make men more responsible in the home (although that wouldn't hurt). But it must involve changes in the labor market, especially how jobs are structured and remunerated to enhance temporal flexibility. The gender gap in pay would be considerably reduced and might vanish altogether if firms did not have an incentive to disproportionately reward individuals who labored long hours and worked particular hours. Such change has taken off in various sectors, such as technology, science, and health, but is less apparent in the corporate, financial, and legal worlds. (emphasis mine)

Goldin wasn’t quite sure how flexible workplace hours could be achieved. But that was in 2014, before the pandemic, before Zoom and Slack and Google Docs came together in a time of need to produce the remote work revolution. Like birth control or the dishwasher, remote work is a technological innovation that appears to be here to stay. Its productivity benefits are becoming more apparent over time, as companies learn ways to profitably restructure their production processes around more geographically distributed, asynchronous teams.

On top of its other benefits, Goldin’s research seems to me to imply that remote work will be yet another boon for working women. Norms change, but slowly and with difficulty. Women shouldn’t have to be the “on-call parent”, but if they want to be, then remote work will make it much easier for them to do that while still holding down a high-powered career. I think that countries that want to improve gender equality — I’m looking at you, Japan and Korea! — should try to encourage remote work.

In any case, Claudia Goldin’s Nobel is richly deserved. She demonstrated a new way to do economics — bringing together a large number of different methods, theories, and data sources to attack one very big, very difficult question. As she puts it, this is economics as detective work.

But Goldin’s research is about more than just understanding the past; it’s about changing the future. There’s a pretty universal tendency to attack social problems like gender inequality head-on — to shout about them and lament them and march in the street. Sometimes this works very well, sometimes not. Goldin showed that this direct approach can be complemented by a coolly intellectual one that attempts to understand social problems at their functional level. By understanding how that technology and supply and demand and incentives complement things like social norms and laws, we can improve our ability to reshape the world to our liking. Knowledge, after all, is power.

Fun story: my wife and I tried to game the system by having me (the father) be the oncall parent. No one thought to mommy track the dad, and then she was able to work full steam and advance her career at the same time. It worked for quite a while!

But, opting for flexibility did eventually catch up with me, and now she earns more than I do. Happened after about ten years.

Here's another comment, because my last one was getting too long.

Anecdote time!

I practice a martial art. Most of the other people in my dojo are men. When I got pregnant, I went to my instructor and explained my situation: I will keep practicing until I start "showing," but I can't exert myself, so I'll have to step back if the practice gets too vigorous, and I absolutely cannot do any sparring where I might get kicked or punched in the stomach. My instructor agreed and was very supportive.

As I went around the dojo and told all my colleagues about my pregnancy and what it meant for my practice, no fewer than four of them beamed at me and said, "Congratulations! BTW, what a coincidence, my wife is pregnant too!"

Over the next few months, as I grew more exhausted and to pull back from practice more and more, finally quitting it altogether, all these men continued to practice as hard and as regularly as ever. Once each man's wife gave birth, he would disappear for about two weeks, then reappear, bleary-eyed and exhausted (these are all good husbands and dads, who did their share of nighttime baby care) but otherwise fit and eager to practice.

I, on the other hand, not only had to stop practice altogether about 4-5 months into my pregnancy; it also took me months, plural, to get back into sufficient shape to be able to return to the dojo. It took me a *long time* to catch up with my male friends once I returned.

The point of this anecdote is: pregnancy is brutal on the body, even "healthy, easy" pregnancy (such as the one I was lucky to have), let alone a complicated one. It's easy to forget when you focus on intellectual jobs, where a person can be thought of as a "brain on a stick" and their physicality and body doesn't matter so much. If your job requires a high level of physical exertion, such as being an athlete, being pregnant/giving birth is a wrecking ball. Even in low-exertion jobs, the reason women take more leave after a baby is born is not just "society's norms dictate that women look after babies," it's to give their bodies some time to heal from the ordeal that is childbirth.

Truly, we won't have 100% gender equality in the workplace until artificial uteri are widely available. I'm kind of kidding, but not really.