You are the heir to something greater than Empire

Our golden age lies in our future, not our past.

“The blood of Numenor is all but spent, its pride and dignity forgotten” — Elrond

“Oh, Daddy was a caveman/ He played ball in skins, with shirts/ He dreamed of lights up in the sky/ While scratching in the dirt” — Tom Orley

I suppose it’s natural, when your country is in a state of steep decline, to take heart in the great achievements of your ancestors. Yishan Wong, the former CEO of Reddit, is from Pittsburgh, but his ancestors are from China. In a long post on X, he expounded a theory that China will always renew itself and rise to meet any challenge, because it’s conscious of its 5000 years of history:

Every kid in China grows up knowing that they're part of a 5000-year-old civilization…What it means is that even if you're a bunch of peasants right NOW, your people have always had civilization. The civilizations aren't perfect or eternal - they rise and fall when the rulers get corrupt and stupid - but civilization is part of the fate of your people, almost the natural default state of things. Even when it's fallen, it's always come back, because that's how your people DO things…

It's like knowing your family has been rich for generations and you're just in one of the down periods. That's different from having been poor and primitive from the beginning of time. It means that Chinese people internalize a default notion of "yeah, we have a civilization, it's just a down period right now, but eventually another strong leader will come about, we'll all work hard, and our civilization will rise again as it has dozens and dozens of times throughout history."…[F]or most Chinese history, China was the world-leading civilization and Chinese people know that…

I was lucky in my youth to work for a boss who was executing a long-term project plan (years long)…The West has less experience like that (on a generational scale). In the 1970s and 80s, China embarked on the long road to industrializing itself…These days, people often say, "it'll take 20 years to get manufacturing started again in the US." And the inherent unspoken response to that is, "oh man, that's too long, I guess we're sunk." But the Chinese response is, "Okay, better start working on it then and we'll have it in 20 years."…

I'm trying to express this deep idea of "they always knew it was in their blood, because it was part of their history."

Now, there are a bunch of reactions you can have to this, and the simplest, object-level response is that it’s a bunch of romanticized nonsense. China didn’t take a longer, harder road to industrialization than the West did — in fact, it’s exactly the opposite. China went from $3000 in per capita GDP to $19,000 in just 34 years; this took the UK more than 200 years, from 1760 to 1976:

It was people in the West who had to endure the long hard slog of gradual industrialization, getting up every day to labor for a future that only their descendants would ever be able to see; China zoomed to modernity in a single generation, taking some shortcuts along the way.

Nor is it the case that China’s current economic ascent is simply a return to former greatness. The Han Dynasty and the Tang Dynasty were certainly mighty and wealthy civilizations for their day, but the industrialization that China has accomplished since 1979 has no precedent or analogy in the imperial past. A long-term graph of China’s living standards looks even more like a hockey-stick than it does for other countries; at the height of Tang power, the average Chinese person was living a life that we’d now think of as one of desperate, inescapable poverty.

Like the rest of us, modern China is in uncharted territory, both in terms of its stunning achievements and in terms of its long-term challenges.

But simply observing that Wong’s reading of history is wrong overlooks the more important point, which is that the story he tells has real power — at least to him, and probably to a lot of other people as well. No, it’s not literally true that China’s modern greatness is a reclamation of past greatness, but if that myth gives Chinese people (or ethnically Chinese people) the confidence to get up and work hard day after day, then it has served an important purpose.

This kind of motivating myth is by no means unique to China. Plenty of White Americans draw inspiration from the greatness of Greece and Rome, or the British Empire. Just yesterday an Iranian tech founder was telling me about the greatness of the Achaemenids. V.S. Naipaul, who grew up in Trinidad, waxed lyrical over the temples of Hampi. A number of Black intellectuals in 20th century America devoted considerable thought to the greatness of past African empires. There are some Jewish Americans who will be happy to tell you about their own “5000 years of history” — after all, by the Jewish calendar, this is the year 5785.1

Some people in the West even trace their own civilizational lineage back to the ancient Egyptians and Babylonians. In his book Why the West Rules—for Now, the historian Ian Morris argues that the “Eastern core” of civilization stays relatively localized to north China and Japan, while the “Western core” has migrated all the way from the Middle East to North America:

The point here is that it’s actually pretty easy to construct a “5000 years of history” story for yourself and your ethnic group, no matter where your ancestors came from.

Logically, telling yourself this sort of story of past civilizational greatness doesn’t make a lot of sense. First of all, people are individuals, and a notional connection to a great civilization or the heroes of the past doesn’t really make you any more of a badass. There are Jewish people who make lists of Jewish Nobel prize winners, but the accomplishments of Einstein or von Neumann will not raise their own abilities by one iota. If Confucius turned out to actually be Korean,2 it would not make one Korean person even the tiniest bit wiser, or one Chinese person the tiniest bit less wise.

I suppose for some people, feeling like they’re descended from greatness gives them more self-assurance. Perhaps it’s a confidence-booster to imagine that there’s some latent variable, unmeasurable on any test, and hitherto undetected in your own career, that will someday enable you to build a great company, or win a Nobel prize, or become a champion League of Legends player, or whatever it is you aspire to. Maybe as you sit there trying to work out a tough math problem on your real analysis exam, you’ll think of Carl Friedrich Gauss, or Srinivasa Ramanujan, or Li Chunfeng, and you’ll think “If my ancestors can do it, so can I!”, and you’ll attack the problem instead of recoiling in terror. Good for you!

The problem with the “civilizational greatness” mode of thinking is that it quickly turns into something zero-sum. The greatness of past civilizations is reckoned at least partly in relative terms — the Romans were great not just because they built the aqueducts, but because they were tougher than the Carthaginians. And if I expect my own “civilizational greatness” to give me a competitive advantage in the modern day, I have to come up with a story about why my ancestors are greater than yours, which means it behooves me to come up with reasons to denigrate your ancestors and spin stories about why their purported greatness was fake.

That obviously gets very stupid, very fast. Social media and web forums are full of people slagging off each others’ ancestors, and I don’t think it’s helping to either build personal confidence or to create a more harmonious society.

Mud-slinging over ancestral greatness also feeds into an even darker sort of conflict — the debate over which ethnic groups are the true owners of the country. A lot of this discourse is based on arguments over who was here first, but some of it is based on the notion of whose group did the most to build up a country. During the 2010s, for example, you saw plenty of claims that “slaves built America” — the implication being that America bears an even greater collective debt to the descendants of those enslaved people today.

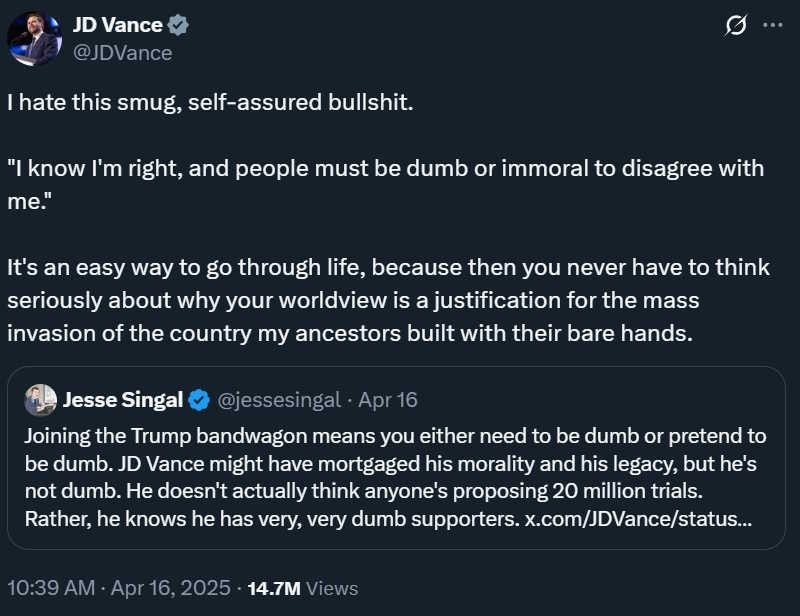

Now, in the 2020s, we’re seeing the reverse claim. In a recent debate on X, Vice President JD Vance justified mass deportations based on the claim that he was defending “the country [his] ancestors built with their bare hands”:

These arguments over which group of people “built the country” are worse than pointless; they serve as justifications for destructive zero-sum ethnic conflict in modern-day America. And they do so by minimizing the future contributions of people whose families just showed up recently in America — or who haven’t even arrived yet.

Which brings me to the second, and most important reason that “ancestral greatness” is an intellectual trap — it’s fundamentally backward-looking, when modernity requires that we look forward.

The notion that we live in a fallen world is a common one; it’s the basis of practically every creation myth, from Eden to the Great Unity to the Silmarillion. There have even been times in history when it was true — a European living in 700 A.D., or a Chinese person living in 1400, wouldn’t be wrong to think that the past had held greater glories. But for a person in the modern world to believe this is simply absurd.

Even just two or three centuries ago, our ancestors lived lives that today would be intolerable squalor. George Washington was a smallpox survivor. Even the rich had bed bugs. Thomas Jefferson, who owned hundreds of slaves, nevertheless wrote repeatedly of his terror of winter. For most people in premodern times, life was a constant struggle for food — even at the height of the Tang and Han dynasties, malnutrition was the norm and famines were common. Death in childbirth was typical, with a rate hundreds of times higher than today. The average American in 1900 would be eligible for special education classes today. Violence was far more common; everyone in the Middle Ages carried a knife. Covid would have been nothing to our ancestors; deaths from disease were many times higher in normal times during the 1800s:

Fantasies of happy medieval peasants, and healthy peaceful hunter-gatherers, are just that — fantasies. The past was a time of constant toil, struggle, hardship, loss, adversity, disease, hunger, violence, and woe. Even in the vaunted 1950s, the big house and white picket fence were reserved for the rich — more than a fifth of Americans lived in poverty in 1959, including 18% of White Americans.

It took us centuries to escape from this brute existence — centuries of war and nation-building, centuries of invention and discovery, centuries of daily toil and backbreaking labor. And Yishan Wong is wrong; nowhere, at any point on that longest of long marches, did anyone have any idea whether the effort would succeed. Whether you were Chinese or European or Indian or Middle Eastern, the conquest of human material poverty was a thing that had never happened before — not during Roman times, nor the Song Dynasty. Never.

It is right and proper to revere and venerate our ancestors — not because they were wiser than us, or because they ruled over great empires, but because they struggled up out of the animal muck into which they were born. They put their shoulder to the wheel and kept going, day after day, through all the sorrow and hardship, and they never quit.

Our ancestors were not wise kings and majestic emperors. They were filthy apes who dared to look up at the stars. That struggle is your blood and your heritage, and it is greater than any empire that has ever existed.

The proper way to honor that legacy is to emulate it — to build more, to keep struggling upward in the present day. To believe that we live in a fallen world is to disgrace every one of our forebears who worked to give us a better future. Instead, we should stay on the path they set out for us, looking forward instead of back.

Squabbling over whose people “built America”, and trying to keep out anyone who doesn’t spring from that stock, is a fool’s errand; instead, we should be welcoming and encouraging the people who will keep building America tomorrow, no matter what part of the globe they hail from. Fighting over whose ancestors were greater is useless; instead, we should resolve to create a great line of descendants. Rather than restoring our societies to the (real or imagined) glories of the past, we should expect to build our societies to peaks never imagined.

That task is what we should take pride in. That is what we owe to the future, and to those who came before.

The only people who can credibly claim to have 5000 years of written history are the Egyptians and the Iraqis. Everyone else is counting prehistory as part of their “civilization”.

He was not.

I'm going to be charitable and say, I understand why during the Great Recession this narrative of "flailing and falling America" took hold. But for the last ten years, I think we can all look with some self reflection and say it has not borne out. And if it becomes true now, it very much can be remedied, no matter how horrible and worst case the next few years are.

I don't know how but we need to take pride on the fact that we have gotten thru it - today is better than yesterday, and if tomorrow is hard than let's take pride the day after that we got thru it. That needs to be our narrative.

Additionally, some self love - this can again be the same country that elected Barack Obama. A country of hope and love, a country that embraces the change and belief in a better tomorrow. A country for all people, built on liberty and wealth. That is a big part of this country's history- bringing a globally diverse group together and shooting for the moon - and it can be the narrative thst inspires is to bring everyone together for an even better tomorrow.

Nice comments and great charts and illustrations, too.

I recall reading (James Fallows, maybe?) after his time in Japan and Malaysia and China that America's superpower is its ability to assimilate and yet have room for differences - you can come here and be Italian, you can come here and be Mennonite, you can come here and be Muslim, you can come here and be Vietnamese - or be whatever you want to define yourself to be. There is room to be different from each other, and out of those differences new solutions arise. And those 1st and 2nd generation immigrants are links back to those parts of the world, so help build bridges and networks and trade.

So siloing into only one cultural heritage is a losing game.

Even China doesn't have one heritage. Dozens of languages across the country, sometimes I'm amazed it can even be considered one country. And after nearly committing cultural suicide in the Cultural Revolution, they adopted a lot (a LOT!) from America, even if they won't admit it.

It's very much a hybrid culture.

Much power in having multitudes within. When you can embrace it, it gives great flexibility and strength.