Will this be the Chinese Century?

Probably yes, though that may not mean what people expect.

Witnessing America’s flamboyantly stupid economic self-harm and its slow descent into authoritarianism has made some people ask whether the 21st century will end up being the Chinese Century. Thomas Friedman says yes:

“There was a time when people came to America to see the future,” [an American businessman in China] said. “Now they come here.”…

President Trump is focused on what teams American transgender athletes can race on, and China is focused on transforming its factories with A.I. so it can outrace all our factories. Trump’s “Liberation Day” strategy is to double down on tariffs while gutting our national scientific institutions and work force that spur U.S. innovation. China’s liberation strategy is to open more research campuses and double down on A.I.-driven innovation…

[W]hat makes China’s manufacturing juggernaut so powerful today is not that it just makes things cheaper; it makes them cheaper, faster, better, smarter and increasingly infused with A.I…China starts with an emphasis on STEM education — science, technology, engineering and math. Each year, the country produces some 3.5 million STEM graduates…[T]he best are world class, and there are a lot of them…

Over 550 Chinese cities are connected by high-speed rail that makes our Amtrak Acela look like the Pony Express.

Matt Yglesias also recently tweeted (and then deleted): “For the first time in my life, I really just think America may be cooked and it's gonna be the Chinese century.”

Tyler Cowen has his doubts, arguing that Chinese success free-rides on a bunch of American-provided public goods:

In the realm of technology, China’s advances are impressive. BYD has the best and cheapest electric vehicles…Chinese AI, in the form of DeepSeek and Manus, has shocked many Westerners with its inventiveness…Yet Western and most of all American hegemony is not over yet. These advances by China are real, but they rest on a foundation of Western values and institutions more than it might appear at first…

The inconvenient truth, for China, is that its scale relies upon American power and influence. The Chinese export machine, for instance, requires a relatively free world trading order…If the world breaks down into bitterly selfish protectionist trading blocs…where will the Chinese sell the rising output from their factories?…

The Chinese growth and stability model also requires relatively secure energy supplies…If the Western alliance system collapses, who is to keep the Middle East relatively stable…China hardly seems up to that task…Another risk on the horizon is nuclear proliferation…The more nuclear powers inhabit the world, the more China is hemmed in with its foreign policy ambitions…

There is much to rue in the first few months of Trump’s foreign and economic policy, but China is far from being able to take the baton. They are running second, and doing a great job of that, precisely because we Americans – in spite of all our mistakes — still have the lead.

Surprisingly, I think Friedman is more right than Tyler here. I’ve written a bit about this topic over the past few years, and I think that when we look back on the 21st century, we’ll probably call it the Chinese Century — or at least, the first half of it.

But the reason I say this is because what it means for a century to “belong” to a specific country will change from what it meant in the 20th — and often in ways that will not be very pleasant.

What does it mean for a century to “belong” to a country?

The 20th century often gets called the “American century”, but there’s no one reason why. It’s just sort of a gestalt impression that the U.S. was the most important country during that century. There were lots of dimensions in which this was true:

The U.S. had the largest economy in the world, and was the dominant manufacturing nation.

The U.S. was militarily dominant, having the world’s most powerful military for almost the entire century.

The U.S. was one of the richest economies, setting the standard for what a modern lifestyle should look like.

The U.S. was a technological leader, producing by far the largest share of the scientific discoveries, breakthrough inventions, and commercial products that changed the world.

The U.S. was culturally dominant, through its output of movies, music, television, games, fashion, and ideas.

The U.S. was geopolitically central; it played a key role in creating and sustaining various international institutions, created the world’s largest and most powerful network of alliances, and provided global public goods like freedom of the seas.

The U.S. was historically central, playing the most important role in shaping many of the key global events of the 20th century — the World Wars, decolonization, the Cold War, and globalization.

In fact, I would argue that our whole modern notion of assigning centuries to countries was pattered after America’s unusual importance across nearly every single domain in the 20th century. It’s hard to think of other historical examples where one country has had such broad-spectrum dominance.

The closest comparison has got to be Britain in the 19th century, which gave birth to the Industrial Revolution and built a globe-spanning empire. But even the UK was never as militarily or culturally dominant as America was in the 20th century. As for older comparisons, only the Mongol Empire in the 13th and early 14th centuries really measures up. The globe was usually just too fragmented, and technological progress too slow, for one country or empire to overshadow all the others. Even the Roman Empire, the Abbasid Caliphate, and the Tang Dynasty were more regional superpowers than global ones.

Anyway, the point here is that there’s no reason that we should believe, a priori, that the 21st century will be dominated by anyone the way America dominated the 20th. The historical norm is multipolarity, with different countries and empires having modest leads in various different dimensions for various periods of time.

Now, you can argue that globalization and continuous technological progress are both here to stay, meaning that future centuries are permanently more likely to have one dominant country. I think that’s probably true to some extent. But as I’ll explain, I also think that the nature of both globalization and technological progress are changing, in ways that will bias the 21st century toward multipolarity.

And some of these changes will result from the power transition from the U.S. to China. Simply put, 20th century America invented the game that it won, whereas China will use its power to invent (and win) a different sort of game.

China’s greatness will be different from America’s greatness

You might be surprised to hear this, but I actually think China and the U.S. are very culturally similar, rather than representing distinct, alien poles of “Eastern” and “Western” civilization.1 But I’m not much of a cultural determinist; I think technology and institutions tend to matter more. Here, the differences outweigh the similarities.

One area where China already far surpasses America is in state capacity. This is from a post I wrote back in 2023:

In his book China’s Economy: What Everyone Needs to Know (which is excellent and which I heavily recommend), Arthur Kroeber offers a grand unified theory of the country’s economy — that it’s good at rapidly and effectively mobilizing lots of resources, but bad at using those resources in an optimally efficient way. So in the case of say, building too many apartments, or failed Belt and Road projects, or wasteful corporate subsidies, the lack of efficiency can really bite. But if we’re talking about building the world’s biggest high-speed rail system, or creating a world-beating car industry from scratch, or building massive amounts of green energy, then China’s resource-mobilizing approach can accomplish things on a scale no other country has ever accomplished before…

Remember a few years ago, when a bunch of people were sharing this map of a hypothetical U.S. high speed rail system?…Of course, the map and others like it were pure fantasy; in 15 years, California’s much-ballyhooed high speed rail project has managed to almost complete one small segment out in the middle of nowhere. That’s the extent of the U.S.’ high speed rail prowess…But in China, they actually built the map!…In the last 15 years, China, starting from scratch, built a high-speed rail network almost as twice as long as all other high-speed rail networks in the world, combined. I’m not exaggerating; you can look these numbers up on Wikipedia. As of last year, China had 42,000 km of high-speed railways in operation, with another 28,000 km planned. That’s compared to just 2,727 km in Japan, with its famous shinkansen.

The U.S. used to have much higher state capacity than it does now, back in the middle of the 20th century — it was able to outproduce all other nations during World War 2, build the interstate highway system, and so on. But modern Chinese state capacity exceeds even America’s peak.

What other nation could have maintained the kind of draconian, micro-managed Covid lockdowns that China kept all the way through 2022? Of course, past a certain point, these lockdowns were probably counterproductive, and they were certainly dystopian. But they were certainly a demonstration of the awesome power of the Chinese party-state.

China is also bigger than the U.S., and so if its economy continues to mature, it will eventually be even more economically dominant. The UN predicts that by 2030, China will represent 45% of all global manufacturing — higher than the U.S. ever achieved except for a brief moment after World War 2 (Update: A more sober estimate is 36%, similar to what America achieved in the late 1920s and early 1960s). But also recall that manufacturing is falling as a percent of China’s GDP, as service industries grow. So unless China somehow turns out to be uniquely weak in the service sector, we can probably expect its overall economic dominance to be just as big as America’s was, or bigger.

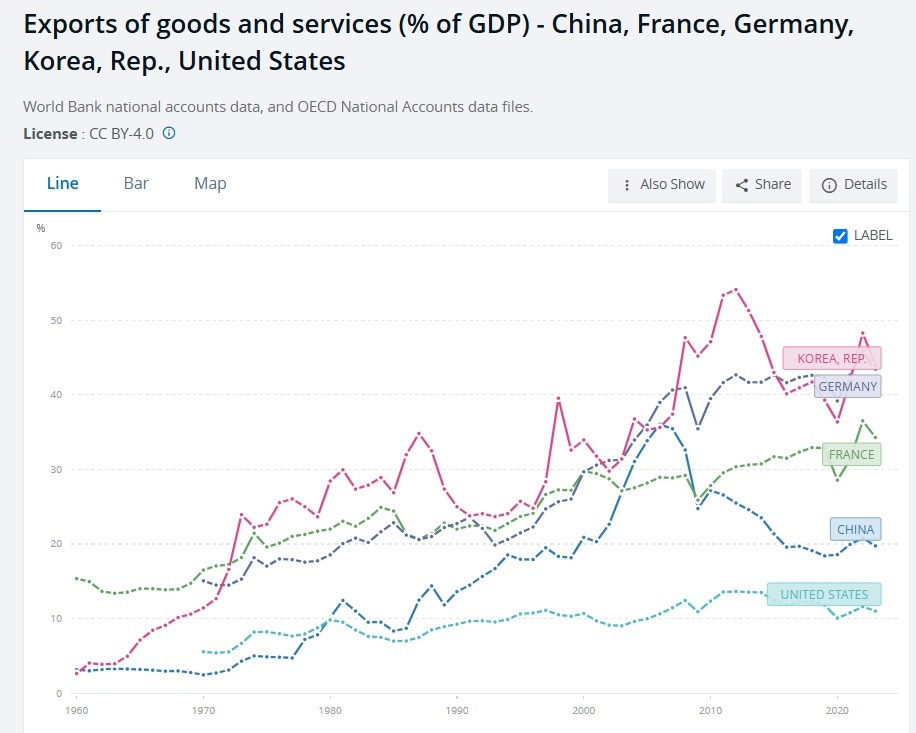

Nor do I think the loss of U.S. export markets will hurt China much. Tyler asks: “Where will China sell the rising output from their factories?”. The answer to that question is “China”. Contrary to popular belief, China is not that export-intensive of an economy, compared to the likes of France, Germany, or South Korea:

China had a brief period of export-oriented growth in the 2000s, but that’s basically over. Now, China sells most of what it produces to Chinese people. Even the vaunted “Second China Shock” is mostly an overflow phenomenon; for example, China has become the world’s top car exporter, but the vast majority of the vehicles it makes are for domestic consumption.

In this sense, China is becoming more like the 20th century U.S. — a very large economy that has some prominent exports but is fundamentally domestically focused. Lack of demand from America is highly unlikely to cripple or even substantively reduce China’s economic progress, especially as the Chinese economy shifts to services.

(And no, China’s current real estate bust will probably not derail its economic rise, any more than the Great Depression permanently derailed America’s.)

With economic dominance will come military dominance. The smaller nations of the world are probably more able to resist conquest and domination by their larger neighbors now, thanks to nuclear proliferation and the shift of technologies toward tactical defense (basically, drones and missiles blow up vehicles, and guns shoot down drones). But China’s size and manufacturing strength will allow it to overwhelm any nation that resists it, and that threat will be enough to overawe most.

But the similarities probably stop there. China’s vast size, smaller resource endowments, and inefficiently high level of government involvement in the economy will probably stop it from attaining the kind of world-beating living standards that America enjoyed (and still enjoys, at least for the moment). China will be the world’s biggest economy, but only because it’s 4 times the size of America; it probably won’t be the richest. This means that although the people of the world may admire China’s vast train stations, soaring skyscrapers, and endless infrastructure, they may not be clamoring for the chance to live as the Chinese live.

In terms of technological leadership, China will certainly shine — but not in the same way America did. In a post last month, I argued that China overall is a highly innovative country, but that due to weak IP protections and other institutional factors, its innovations tend to be a blizzard of incremental improvements with few dramatic breakthroughs:

To American ears, this sounds like a condemnation of China’s system, but to China’s leaders this is probably just fine. If China simply appropriates or copies any new invention and scales it up more efficiently than anyone else can, it still comes out on top. And my sense is that coming out on top is far more important to China’s leadership than furthering the aggregate progress of human knowledge and prosperity.

If weak IP protections discourage breakthrough discovery and invention all over the world, so what? That just reduces the risk that the rule of the Chinese Communist Party will be destabilized by the emergence of new techno-economic paradigms.

Some might argue that AI will change this equation. If people all over the world are able to create breakthrough innovations on their mobile phones using open-source AI algorithms, the cost of breakthroughs might come down so much that IP protections don’t really matter. If so, the world will enjoy a technological golden age. But even in that scenario, China will likely be able to appropriate, scale, and commercialize all of those innovations. It will still be the technological leader, just not the kind the U.S. was.

In the cultural realm, I expect China to be more isolated and less influential than America was. Partly this is because of language — English is far more internationalized than Chinese will ever be (though AI will erode this barrier significantly). But partly it’s because of social control. China is a deeply repressive nation, with universal surveillance, fine-grained media and speech control, and ubiquitous censorship. That’s the kind of society where only anodyne, cautious artistry can flourish, except in tiny subcultural pockets too small for the government to worry about.

China’s leaders will also probably remain paranoid about allowing in foreign ideas. They will continue to use the Great Firewall to “protect” Chinese people from the memes and ideas produced by the rest of the world. So artistic and cultural ferment will arrive in China only weakly, and with a lag. It will be orphaned from the global discussion, and the country’s creativity will instead be channeled into the technological and commercial space.

So while I expect China to produce some hit video games and big-budget movies, I don’t think it will do much to push the boundaries of culture, despite the individual creativity of its people. Chinese tech products like TikTok will have an influence on global culture, but the key content will be produced elsewhere.

As for geopolitics, I think Tyler is certainly right that China will provide fewer global public goods than America did. It will be less interested in creating freedom of the seas for other nations, and more narrowly concerned with protecting its own trade. Its military will make sure energy supplies reach Chinese shores, but probably won’t be interested in making energy globally abundant. Research is another example; China’s government will make sure China dominates every frontier technology, but won’t care as much about expanding the frontier. And global security is yet another; for all the sneers directed at America’s self-appointed role of “world police”, it was more willing to stand up to regional conquerors than China has proven so far.

But I think Tyler overestimates the negative impact on China from the collapse of American public good provision. If America stops protecting Chinese shipping and energy supplies, China’s military will become perfectly capable of doing it themselves. There is nothing unique about the U.S. Navy, just like there was nothing unique about the British Navy. And in fact, since I predict China will guard only its own trade and energy supplies and leave other countries out to dry, the Chinese Navy may be able to accomplish its goals more cheaply than the U.S. could.

In other words, I expect China to be a far more selfish power than America was in the late 20th century. It’ll be more like the U.S. of Teddy Roosevelt’s time — mostly inwardly focused, but occasionally intervening in smaller countries’ affairs out of economic self-interest or desire for glory. International institutions and forums will become either irrelevant or will be vehicles for China to boss smaller countries around.

In sum, I predict that this will be a “Chinese Century”. This may not hold as strongly in the second half, when China’s low fertility rates start to bite and India really starts hitting the top of its own trajectory. But for the next few decades at least, I expect China to be the world’s preeminent economic and technological power — a historically unmatched marvel of size, resource mobilization, and innovation. America’s orgy of self-destruction will only hasten this future.

And yet I think that the Chinese Century will be disappointing in many ways, especially to people living outside China itself. A world where every invention gets grabbed and copied by Chinese state-sponsored companies is a world less filled with wonder (though AI may help here). A world where Chinese warships guard Chinese trade and leave other nations to fend for themselves is a more chaotic, less secure, less egalitarian world.

A world where China produces everything for itself but has no need of foreign manufactures is one where other developing countries have less opportunity to grow. A world where China tolerates regional conflicts and preserves peace only in its own backyard is a more dangerous, violent one. And a world where the premier nation hides its culture from everyone else is a more drab, less creative one.

In other words, I’m more confident than Tyler about China’s ability to prosper, build, innovate, and dominate in a world where America collapses in on itself. I think Thomas Friedman is right, and that unless something big changes, China is headed for at least half a century as the globe’s preeminent power. But that prospect makes me fairly glum, because a Chinese Century will, in many ways, be a downgrade from the American Century. Perhaps the U.S. efflorescence was a very rare and special thing, whose like we will not soon see again.

This deserves a much longer post, but in brief: America never had a single traditional culture, while China destroyed much of theirs in the Maoist period. Both countries have substituted consumerism and technological progress for traditional cultural relationships. Americans and Chinese people both dress sloppily, cut corners at work, and drive to the mall in crocs and shorts, eat high-calorie greasy food, and harbor grandiose, vague, usually unrealistic dreams of personal wealth and success. On the other hand, both maintain close, often contentious family relationships, with “amoral familism” a widespread attitude in both places. Both have a passion for real estate. Both are large, diverse nations, with deep social divisions; in America these are mostly racial, in China they’re mostly urban/rural and class divisions, but they function similarly. In addition, both “Han” and “white” are synthetic ethnicities created to unify large, diverse populations. Both Americans and Chinese people tend to have pride in the size and power of their countries. It is my casual observation that Chinese people assimilate to American culture even faster than other immigrant groups, and Chinese people feel markedly less “foreign” to me than people from Europe, Canada, or Australia. Your mileage may vary, of course.

My idle speculation from a an armchair in China is that while the ‘American century’ sure feels like it’s ending there is no sense of a ‘Chinese century’ beginning. Like the scale here is another level. But it does not feel futuristic because the same technology is already there in all the developed world. Just in far smaller quantities. And the middle income features feel anachronistic.

Maybe this is just the interregnum. Or maybe one simply cannot call these things in advance.

It’s curious that you mentioned in the footnote that Canadians or Australians feel more foreign to you than Chinese immigrants do. Could you elaborate on that?