Why you should not ignore economists

They aren't always right, but they almost always have something important to add.

I’m really liking most of what I see from Kamala Harris’ campaign so far, but I disagreed with her about “anti-price-gouging” policy. Fortunately, as Jerusalem Demsas reports, Harris has clarified that she doesn’t support price controls or endorse Elizabeth Warren’s bill from 2022:

When I asked the Harris campaign for clarity, a senior campaign official told me that Harris was not supporting price controls, nor would her proposal to go after price-gougers apply beyond food and grocery stores. After some prodding, the official confirmed that this meant Harris had not endorsed the Warren-Casey bill…The official also [said] that adding in too much detail could be deceptive given that the real policy-making process requires time, effort, and negotiation.

My objections were based on the assumption that Harris was endorsing Warren’s ideas about price controls; instead, it seems like she’s simply throwing out some populist rhetoric. Which means I’m no longer worried about this issue. Unlike the GOP, the Democrats have a candidate who can be relied upon to listen to the relevant experts and avoid taking extreme and dangerous policy steps.

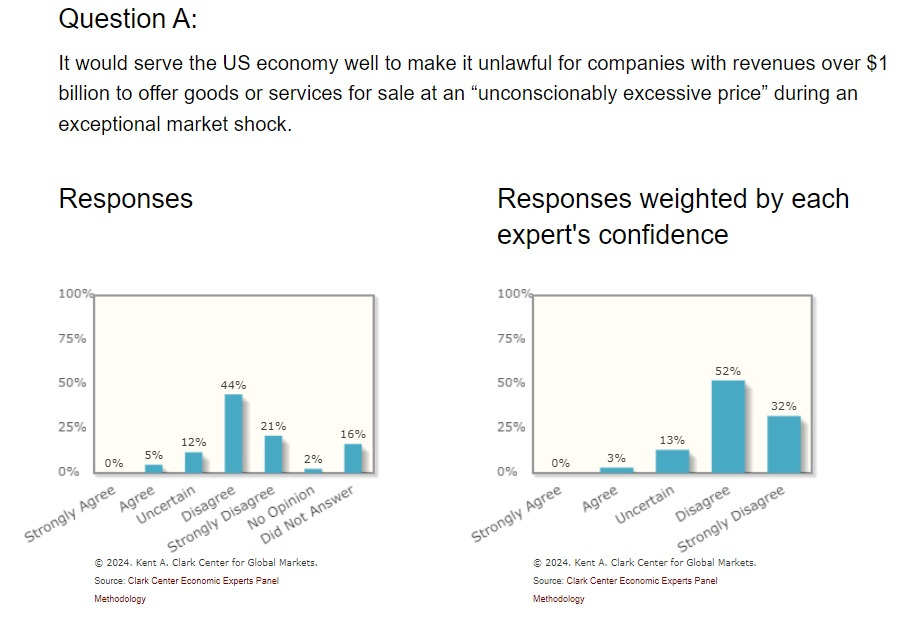

In this case, the experts were economists, most of whom are against “anti-price-gouging” efforts and price control type policies in general. Here are a couple of representative polls from the Clark Center’s Economics Expert Panel, which is a survey of a few dozen top economists:

But some progressives don’t think economists should be regarded as experts on economic policy. They believe that popular conventional wisdom should take precedence when it conflicts with the opinion of academic economists. An example is Fordham law professor Zephyr Teachout, who wrote an article in the Atlantic entitled “Sometimes You Just Have to Ignore the Economists”. Here are some excerpts:

Price-gouging bans are broadly popular—except among economists. The reason is that, in the perfect world of simple economic models, allowing sellers to charge whatever they want during periods of heightened demand is actually a good thing: It signals to the rest of the market that there’s money to be made on the product in question, which in turn leads to more supply…Plus, letting prices rise helps ensure that the product will be sold to the people who value it the most.

Here, regular people seem to understand a few things that economists don’t. During an emergency, such as a natural disaster, short-term demand cannot be met by short-term supply…A short-term price spike won’t always trigger the long-term investments needed to increase supply, because everyone knows that the situation is, by definition, abnormal; they can’t count on a continued revenue boom. During a rare blizzard, sellers might jack up the prices of snowblowers. But investors aren’t going to set up a new snowblower-manufacturing hub based on a blizzard, because by the time they had any inventory to sell, the snow would long be melted.

Interestingly, Teachout misunderstands the simple economic model that she’s criticizing here. I don’t think any economist believes that a price spike in response to a single blizzard generates a supply response. Instead, what happens — at least, in the simple model — is that companies understand that blizzards are a thing that occasionally happen, and plan their supply accordingly.

A blizzard is not like an asteroid strike or a supervolcano eruption. It’s incredibly easy for any corporate employee to go to weather.com and get data on how common blizzards are. So if corporations can charge higher prices during blizzards, they will plan to make more stuff, because they know that blizzards will come along every so often. This is true whether the price increases come from higher costs or from higher profits. Even if price increases only reflect the increased costs of delivering supplies during a blizzard, as long as profits are positive, it still makes sense to make more stuff to meet the increased demand.

That’s the simple model, anyway. Teachout dismisses it based on what she feels to be simple common sense. But because she misunderstands the model, she’s far too quick to dismiss the idea that price controls during blizzards will limit supply over the long term.

Teachout also fails to grapple with a second reason to worry about price controls during “abnormal market disruptions” — they can lead to hoarding. Consumer goods get scarce during a blizzard, and price spikes are a way of rationing scarce goods. If prices don’t rise, and if there’s no way to ration purchases to individuals1, a few people can rush in and buy up all the toilet paper or peanut butter on the shelves. Everyone who lived through Covid remembers what happens when people hoard. But when prices soar, it means that most people can’t afford to hoard. Also, if anti-price-gouging controls are in place, people may hoard in expectation of a blizzard, even when one doesn’t materialize, just to get ahead of the rush.

Modeling hoarding behavior isn’t simple — it’s actually kind of hard, because it depends on a bunch of stuff like expectations, strategic interactions, irrationality, and so on. Common sense won’t give you an easy answer when it comes to preventing hoarding — this is why the economics discipline has smart academics who work on the problem. If those smart academics tell you that anti-price-gouging laws will make hoarding worse, they might be wrong, but you can’t just wave away their arguments and common-sense your way to an answer you like better.

So Teachout tries to demonstrate why economists aren’t useful on the price-gouging issue, yet ends up demonstrating the opposite. And yet on the other hand, she follows up her dubious point about supply with an argument that actually does make quite a lot of sense!

The other big problem with the textbook economics take on price gouging is the assumption that temporarily higher-priced products will find their way to the people who value them the most….During a power outage, a working-class cancer patient who desperately needs to buy the last generator in stock to keep his medications refrigerated might not be able to outbid a healthy millionaire who just wants to run their air conditioner.

This is another way of saying that price-gouging bans are a form of moral policy…All parents, not just the wealthiest, should have an equal chance to obtain diapers even if supply chains are disrupted. Price-gouging laws represent a different set of market rules, grounded in fairness.

In fact, this is an argument that economists often make for various forms of rationing or government provision of goods. In an incredibly influential article in 1963, Kenneth Arrow — a Nobel-winning economist whose work underlies much of the modern discipline — argued that the health care industry has a moral dimension that makes typical market approaches untenable. And in a short paper in 1977, Martin Weitzman — the same economist who did the work on hoarding that I cited above — showed that when inequality is very high, allocating goods randomly can actually be better for the general welfare of society than using prices to ration things.

Of course, that short Weitzman paper is just a thought experiment — it doesn’t take things like long-term supply responses into account, and it just assumes hoarding is impossible. But like Arrow’s paper and many others, it shows that economists are not the simple robotic proponents of free markets that Teachout and some other progressives assume them to be. Economists think about fairness, and equality, and all the other stuff that normal people care about.

There is a caricature of economists as priests of unfettered capitalism, using their theories to justify free-market policies instead of trying to actually figure out how the world works. But in a post back in 2021, I pointed out that much of the economics literature is now dominated by the problems of unfettered free markets:

The free-market revolt is over. Economists’ concern about inequality is growing rapidly, as evidenced by the language economists are using in their papers. Here’s a graph of just one example:

It’s not just language, though. A large number of major research programs are now dedicated to finding ways that government can act to fix the economic problems besetting the U.S. and the world. Some of these include:

The study of inequality (and of taxation that could reverse it)

The study of labor market monopsony (corporate power that holds down wages)

The study of monopoly power and the new antitrust movement

The study of cash benefits

The Opportunity Insights program and parallel efforts to study and reverse falling mobility

Renewed interest in racial disparities

The new minimum wage literature

The new development economics

The new economics of poverty

…and so on.

Meanwhile, the institutions of the profession are becoming dominated by more and more intervention-minded scholars. For example, the last seven presidents of the all-important American Economic Association have been:

Richard Thaler, one of the inventors of behavioral economics

Robert J. Shiller, who wrote a book about how fraud and deception are fundamental to free markets

Alvin E. Roth, an economist who helped devise mechanisms of centralized allocation for things like organ transplants

Olivier Blanchard, a centrist macroeconomist who has been leaning more and more toward government intervention

David Card, who did the original research showing minimum wage isn’t so bad, and is one of the main champions of the empirical turn

Meanwhile, young high-profile economists tend to be champions of government intervention and foes of inequality.

I suppose that just because many economists hold progressive views doesn’t mean that progressive activists and intellectuals need to pay attention to them. Zephyr Teachout and other advocates of anti-price-gouging laws know what policies they want, and they don’t need Martin Weitzman or Ken Arrow to sprinkle holy water on their ideas.

But it’s often very helpful to have smart thoughtful people who have the same goals as you, and who have thought deeply and rigorously about how to achieve them. Sometimes they can furnish you with arguments to help your cause. Sometimes they can flesh out your policy proposals with practical details, to help them achieve greater success. Sometimes they can even tell you when you’ve made a misstep and need to rein it in.

And on top of that, if you’re someone who actually cares about about understanding how the world works, economists can help you with that too. Just because economists care about inequality and other social problems doesn’t mean the profession has exchanged a libertarian religious canon for a progressive one.

Now, that isn’t universally true. Joseph Stiglitz, a darling of progressive think tanks for his broadsides against neoliberalism, once praised Hugo Chavez’ economic policies despite ample evidence that they were leading the country over a precipice.2

But this is the exception rather than the rule. Research suggests that although economists are influenced a bit by their personal ideologies, this influence is pretty limited, and economists don’t end up falling neatly into progressive or conservative ideological blocs.

For example, Gordon and Dahl (2013) studied the Clark panel of top economists that I cited above, and they found that economists can’t easily be clustered into liberal and conservative camps:

The results so far do nothing to identify panel members with conservative versus liberal views…[W]e tried two different approaches. In the first, we looked for clusters in the data…The data show no systematic evidence of clustering into two or even a few roughly equal-sized camps, yielding only weak evidence that three or four idiosyncratic individuals differ from the rest of the sample, and from each other. As a second approach, we focused on the subset of questions that we flagged previously as likely to generate disagreements due to distributional concerns or due to debates on the possible importance of market failures…If there were liberal and conservative camps…some [economists] would consistently give the “Chicago price theory” response and others would consistently give the opposite response…There is no support for different camps in our data, only idiosyncratic views among some Panel members.

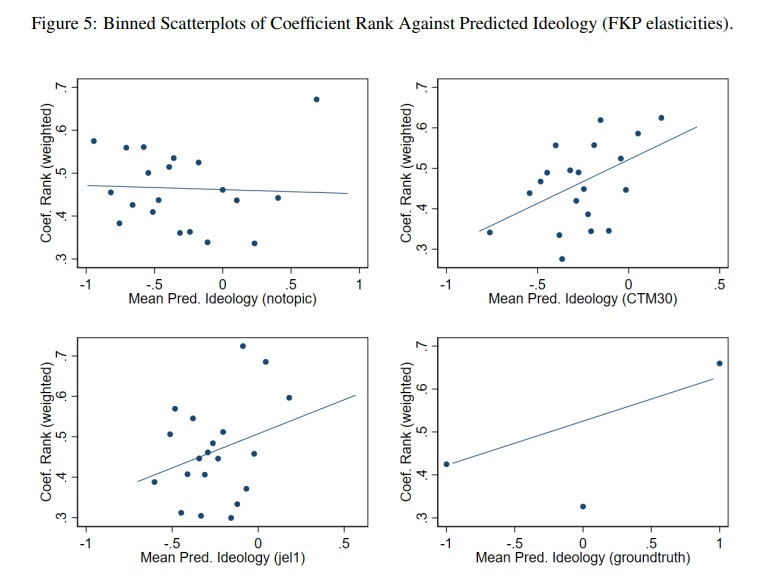

Jelveh, Kogut, and Naidu (2022) take a different approach, using text analysis of economists’ papers to predict which researchers will reach broadly anti-government conclusions, and which will reach pro-government conclusions. It turns out that there is some predictive power there — economists who use generally right-coded language tend to predict worse results from government intervention, and economists who use generally left-coded language tend to say government intervention is good. But the tendencies are not very strong! If you plot out the data of research findings versus ideology, it looks like a mostly random cloud with very little predictive power:

So while every researcher has their biases, economists are not generally either progressive shills or libertarian shills. Which means that they’re mostly focused on just figuring out how the world actually works.

In fact, economists have been doing a lot more of this as the decades have gone by. There’s a well-documented trend of econ becoming more empirical and less theoretical since the 1980s. Empirical studies can be influenced by ideology, but it’s a bit harder to massage data to reach your desired conclusion than to write down a theory that gets you the results you want. More and more of what academic economists do is just about finding the facts.

Even if you’re utterly dedicated to a certain political movement, it is important to have some understanding about how the world really works. If your ideology tells you to build a dam, you need to consult civil engineers who will tell you if it’s actually feasible. If you don’t, you could end up with a lot of drowned citizens.3

Economists don’t know everything, and they can often get things wrong — the fact that different economists disagree with each other on almost every issue is proof of their fallibility. An economy is inherently both harder to study and harder to control than a bridge or a jet engine or a particle accelerator — getting reproducible, dependable, broadly applicable results in social science will always be an uphill battle. But economists know a lot of facts about the economy, they have a lot of data and a lot of good statistical methods, and once in a while they even have a theory that consistently works. They are an intelligent, meticulous, professional, and highly informed bunch, and listening to people like that rarely makes you dumber.

Now having said all that, I do think that there is one big problem with economists’ policy advice (beyond the inherent difficulty of drawing firm conclusions about large social systems). Econ is a deeply hierarchical profession, where the intellectual authority of the most prestigious researchers receives far too much deference.

Anyone who has been in econ academia knows this very well, but there’s actually evidence supporting it. Javdani and Chang (2019) did an experiment on economists themselves, and found that they gave much more credence to ideas that they thought came from prominent mainstream figures in the field:

Using an online randomized controlled experiment involving 2425 economists in 19 countries, we examine the effect of ideological bias on views among economists. Participants were asked to evaluate statements from prominent economists on different topics, while source attribution for each statement was randomized without participants’ knowledge. For each statement, participants either received a mainstream source, an ideologically different less-/non-mainstream source, or no source. We find that changing source attributions from mainstream to less-/non-mainstream, or removing them, significantly reduces economists’ reported agreement with statements. This contradicts the image economists have of themselves, with 82% of participants reporting that in evaluating a statement one should only pay attention to its content.

Occasionally, this deference to authority can lead to a sort of cascade failure where a few old guys get some basic things wrong, and everyone else has to either humor them or challenge their mistakes only slowly and incrementally. A particularly egregious example of this is in the case of climate economics. I wrote a post about this back in 2021:

The basic story here is that a few prominent researchers in the field made some basic errors when assessing how damaging climate change could be. The younger researchers knew that the old guys had messed up, but because of the culture of the profession, it took them a very long time to start pushing back on the mistaken conventional wisdom. But policymakers realized very quickly that the climate economists were downplaying the threat, and decided to ignore them in favor of technologists, policy wonks, and (occasionally) activists. As a result, the field of climate economics became almost completely marginalized, and is only now starting to claw its way back to a position of influence.

So economists shouldn’t be treated as sages, nor their advice as received wisdom. They should not be the only experts consulted when making policy. But it’s always worth hearing what they have to say. The idea that they are free-market dogmatists whose stale and simplistic ideas can be waved away with an appeal to common sense is badly mistaken.

In fact, as we found during Covid, rationing is really hard, because if you want to hoard, you can go buy toilet paper at a bunch of different stores.

There’s an interesting parallel with Milton Friedman’s praise of Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet in the 1980s. Pinochet’s policies, while not nearly as disastrous as Chavez’s, have been vastly overrated by history; Chile only really began to grow and prosper once they kicked Pinochet out.

Even in the extreme case that you don’t care if a bunch of your citizens drown, you’ll need to understand how the world works if you want to hold on to power. Stalin and Mao managed to hang on to power even after collectivization of agriculture killed millions of their citizens, and the British managed to rule India for a long time despite famines caused by bungled economic policies. But in a democratic society like the United States where leaders can get tossed out for having an inflation rate that’s a couple of percentage points higher than normal, it’s important to produce results that the voters like.

Very good article. Based on my interactions with people I think the issue people have with economists is that people really want to tell a moralizing story which reflects their values and says who is a good guy and bad guy. Economic results tend to interfere with that desire.

I think that has some important implications about things like belief in global warming. If you want conservatives to listen to those experts it's really important to disassociate them with moral language/accounts (eg seeing nature as valuable in itself not there to serve man, degrowthy values) to the maximum extent possible.

Noah, I am a long time reader and like most of what you have to say. But saying that you are "really liking what you see from the Kamala campaign", when, essentially, there has been NOTHING other than some jiggling around, some cackling, and (on day one) 142 deprecations of Donald Trump (whether merited or not, that is not really what anyone needed to hear) you blunt your own credibility. I look daily and have seen no policy statement other than her price control statement, which she quickly walked back because it was populist but so unconnected to reality that even the plebes caught on that she was economically illiterate.

So if you have a magic source that allows you to see anything other than laughing and gyrations, would you share it with us? Some of us have looked high and low and have found, essentially, nothing.

Of course the real question for those who are not already pre-sold down the river is if she has so many great ideas, why did she not implement any of them the first four years, but all of a sudden is sure that (whatever they are) she will implement then the next four because...

You seem to retreat to an approach that she will just rely on the expertocracy and that will be great. I am an expert on infectious diseases and can tell you that the expertocracy was dead wrong on virtually every part of the covid response. Krugman is wrong every day. So while I agree that expertocracy has some merit, that approach provides little solace.

You must know something the rest of us have been unable to find. I hope you will share it so that we will all know.