Harris makes a big mistake by embracing price controls

Don't turn to the dark side of progressive economics.

I’ve been doing a series of posts on the substantive ideas of the two presidential campaigns. I talked about Biden’s policies back in May when he was still running, and when he dropped out I wrote a post about his legacy. On the Trump/GOP side, I wrote about Trump’s terrible idea for revoking the Fed’s independence, analyzed the RNC platform piece by piece, discussed the possible upside of tariffs on China, and argued that mass deportation of illegal immigrants would do no good for the economy, while spreading fear and division. Now it’s time for some posts about Harris’ ideas.

Today I want to talk about Harris’ first big policy announcement — a call for price controls on food and groceries. Here’s the story, from the Washington Post’s Jeff Stein:

Vice President Kamala Harris on Friday will unveil a proposed ban on “price gouging” in the grocery and food industries, embracing a strikingly populist proposal in her most significant economic policy announcement since becoming the Democratic Party’s nominee.

In a statement released late Wednesday night, the Harris campaign said that if elected, she would push for the “first-ever federal ban” on food price hikes, with sweeping new powers for federal authorities…

Harris’s plan will include “the first-ever federal ban on price gouging on food and groceries — setting clear rules of the road to make clear that big corporations can’t unfairly exploit consumers to run up excessive corporate profits on food and groceries,” the campaign said in a statement.

The exact details of the campaign’s plan were not immediately clear, but Harris said she would aim to enact the ban within her first 100 days, in part by directing the Federal Trade Commission to impose “harsh penalties” on firms that break new limits on “price gouging.” The statement did not define price gouging or “excessive” profits.

Price controls on food are a really terrible idea. The best-case scenario is that the controls are ineffectual but create the legal and administrative machinery for far more harmful controls in the future. The worst-case scenario is that they cause shortages of food and groceries, leading to mass hardship, exacerbating inflation, and setting America up for increased political instability.

If you want to defend Harris here, you pretty much have to assume that this is a populist proposal that she’ll eventually backtrack on once in office, or fail to get passed. After all, in the final days of his campaign, Biden floated a (very bad) proposal for national rent control — an idea he had never embraced in his presidency, and which was probably just a Hail Mary pass. But Harris explicitly said that price controls on groceries are something she’d do in her first 100 days as President, and candidates tend to be serious when they say that.

It’s also a very bad sign that Harris intends to use executive power to implement price controls. She appears to believe that the Federal Trade Commission can impose penalties on companies that “price gouge” — i.e., that raise their prices more than the administration believes is warranted. I am not a lawyer, but the idea that the FTC can go in and simply tell a Kroger’s in Michigan what price to charge for eggs seems like a vast expansion of the agency’s powers.

The FTC has the power to stop price fixing, but that’s something very different — price fixing means when multiple companies illegally collaborate to keep their prices high instead of competing. It’s dealt with under existing antitrust law, and the FTC has to sue companies in court to get them to stop it. I see no reason to believe that existing law allows the FTC to act like a central planning authority that can simply dictate what every grocery store in the land can charge for eggs, milk, diapers, and toilet paper.

So my guess is that the kind of price control regime Harris has in mind would require an act of Congress. I don’t know if she could get it passed, or if SCOTUS would strike it down, but if it succeeded, it would create the legal machinery for the kind of disastrous spiral of price controls, “hoarding” crackdowns, and shortages that brought down the economy of Venezuela.

(Side note: None of this makes Harris worse on economics than Trump, whose proposals to have the President set interest rates and enact 20% tariffs on U.S. allies are also terrible.)

Anyway, the real tragedy here is that price controls on groceries are completely unnecessary. Inflation has already been pretty much defeated, and grocery store greed was never the culprit behind price increases in the first place.

Price controls are a “solution” for problems that don’t even exist

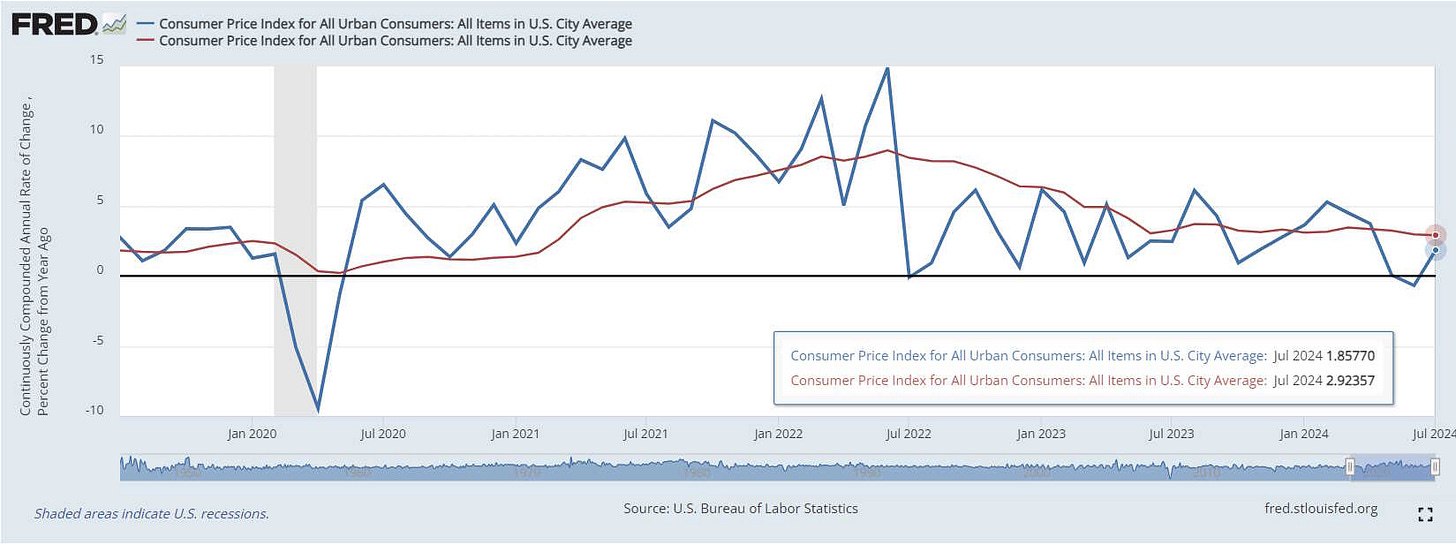

First of all, let’s talk about the inflation situation. CPI inflation, which is the number that news outlets pay attention to, is basically back to its 2% target. On a monthly basis it’s been below target for three months, while on a year-over-year basis (which it’s down below 3%:

PCE inflation — the number the Fed is officially supposed to pay attention to — hasn’t come out for July yet, but the numbers look similar. In fact, no matter what inflation measure you use, it’s clear that inflation is back down to around the 2% target. Jason Furman has a table of various inflation measures, and they all tell the same story:

Across the board, inflation is way down for all sorts of consumer goods.

Now, this doesn’t mean that the danger of inflation is gone — it could still come back, if Trump forces the Fed to cut interest rates too much, or if we make some other stupid policy mistakes. But actual inflation right now is not a big deal.

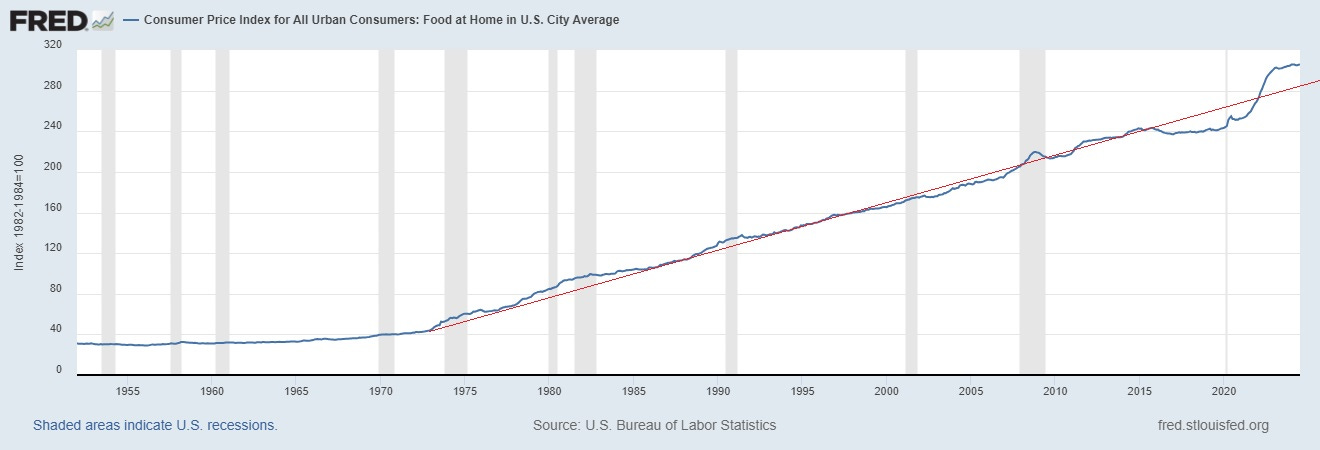

Now you’ll also notice that in Furman’s table, “Core ex shelter” inflation is lower than the other numbers. That’s because inflation for everything except rent has collapsed. In particular, grocery inflation (“food at home” in the CPI) has been hovering around zero since the beginning of 2023:

Here’s what that looks like in terms of the actual price level. You can see there was a big increase in 2021-22, but then prices flatlined:

We already beat grocery inflation. It’s over. Harris’ big policy scheme is aimed at a problem that no longer exists.

Now, many people will argue that what Americans care about isn’t grocery inflation itself — which is the rate of change of prices over a month or a year — but the actual price level. And this makes sense — if prices rise a lot and then stop rising, people will still care that they rose in the past.

But it’s also true that grocery prices were unusually low in the 2010s. Instead of continuing the trend of slow, steady increases from earlier decades, they remained flat for a while. In that sense, maybe half of the big price increase of 2021-22 was just “catching up” to the old trend:

And more importantly, what people probably care about even more than the price of groceries is how much groceries they can afford. And when we divide wages (average hourly earnings for production and nonsupervisory workers) by the price of groceries, we see that while purchasing power did take a hit in 2021-22, regular workers are able to afford more groceries in 2024 than in 2019:

Steady wage increases and the flatlining of grocery prices have canceled out most of the drop in purchasing power that happened in 2021-22. People may still be a bit grumpy over being able to afford only slightly more groceries that they could buy in 2019, but it doesn’t seem like the kind of popular rage that requires a dramatic policy fix.

What’s more, there’s no indication that grocery store profits have anything to do with the rise in grocery prices in 2021-22. The reason is that grocery stores make almost no profit, and their profits barely increased at all when grocery prices went up:

You can see from this chart that the big increase in prices didn’t translate to a big increase in grocery store profits. A 3% profit margin is very low — the S&P 500’s average profit margin is 11.5%! In fact, grocery stores are a notoriously unprofitable business in general:

Grocery stores consistently have among the lowest profit margins of any economic sector. According to data compiled this month by New York University finance professor Aswath Damodaran, the entire retail grocery industry currently averages barely more than 1 percent in net profit. In its most recent quarter, Kroger reported a profit margin of 0.75 percent[.]

The reason grocery store margins are low is that the business is incredibly competitive. The biggest chain is Kroger, with a market share of only 16% and a profit margin that’s consistently under 2%. The grocery industry is capitalism working as it ought to work, bringing food and daily necessities to Americans at a cheap price. When those prices rose, it was because grocery store costs rose.

(Side note: In fact, this is generally true of the entire 2021-22 inflation episode. Despite the widespread belief among progressives that the inflation was due to price gouging or “greed”, changes in price markups were uncorrelated with price increases in 2021-22, and industries with more monopoly power actually saw fewer price increases during that time. As Matt Bruenig explains, and as I’ve also argued, the entire “greedflation” narrative was wrong.)

Now, that doesn’t mean there’s no monopoly power problem in the food industry! In a post in December 2023, I argued that if there’s anyone jacking up prices, it’s not grocery stores or farmers, but the middleman businesses who process food:

There is anecdotal evidence that there are monopoly issues in the food supply chain, especially in meatpacking. The top 4 companies in that industry are very dominant, and Matt Yglesias points us to a recent price-fixing lawsuit against big meatpackers. (Though it’s also notable Tyson Foods’ profit margin collapsed during the recent inflation.) So monopoly power in food processing is worth investigating, and possibly prosecuting with standard antitrust tools.

But this has nothing to do with Harris’ proposal to have the government outlaw price increases at grocery stores. Grocery store “price gouging” is not why groceries are expensive in America, and mandating that they keep prices low will not counteract the forces that made groceries more expensive in 2021-22.

This isn’t a case of “the cure is worse than the disease”. It’s a case of treating a disease that the U.S. economy doesn’t actually have with a “medicine” that isn’t actually a cure.

Price controls can wreck an economy

Let’s talk about the dangers of price controls, because they’re big.

First, think about what would happen if the President of the U.S. managed to impose price controls on grocery stores. As we saw in the last section, these stores have razor-thin profit margins — when they increase prices, it’s because they’re paying higher costs. If the stores are forbidden from raising prices when costs go up, the government will be forcing them to take a loss.

What will the stores do if the government forces them to take a loss? They will sell less stuff, because they’re taking a loss with every sale they make. Shelves will go empty, just like they did in the Soviet Union, and just like they did in Venezuela.

When people hear the words “Soviet Union” and “Venezuela” in connection with the U.S. economy, they often roll their eyes. Those regimes were dysfunctional in a very large number of ways — price controls were only a piece of the story in each case. But that doesn’t mean basic economic operates differently in the USSR or Venezuela than it does in America. The economic logic of price controls in a competitive industry like groceries is basic Econ 101 supply-and-demand stuff. The good old Econ 101 supply-and-demand model doesn’t work in all cases, but it’s very good at explaining exactly why price controls cause shortages in highly competitive industries:

Yes, we’ve all grown tired of libertarians and free-market types shouting “It’s just Econ 101, bro. Do you want to be the Soviet Union?” every time anyone proposes a government intervention in the economy. But in this particular case, they happen to be correct!

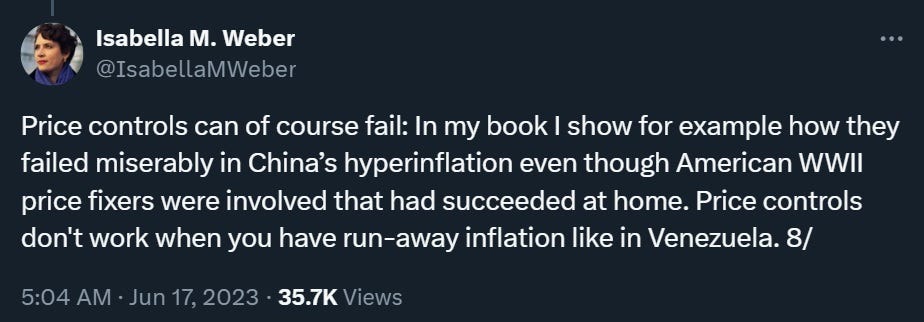

Even many prominent advocates of price controls, like Germany’s Isabella Weber, think of them as a specific tool that can be very dangerous if applied in the wrong situations:

If we look at history, we see many examples where price controls had big negative effects. We see basically no examples where they had a positive effect. World War 2 in the U.S. isn’t a good example, because there was also wartime rationing — the government put a cap on demand for consumer goods, which made the price controls a bit beside the point.

One example of price controls that seemed not to have much effect was Argentina. Aparicio and Cavallo (2021) find that from 2007 to 2015, these price controls had little effect on the economy one way or another:

[T]he impact of targeted price controls on aggregate inflation is small and temporary. At the microlevel, controlled goods are sold at government-agreed prices, which are on average 3.3% lower than before the control, but these are compensated by similar price increases soon after the controls are removed…. At the macrolevel, the inflation rate of controlled goods fluctuates between periods of marginally lower and higher inflation relative to other goods, with no significant impact on the aggregate inflation rate.

Second, contrary to common belief, we find that controlled goods are seldom discontinued and that their availability is similar to that of noncontrolled goods. They have a higher probability of going temporarily out of stock, but stockouts are short-lived and goods are only occasionally discontinued…Overall, our results suggest that targeted price controls are just as ineffective as more traditional forms of price controls in terms of reducing aggregate inflation[.]

There was basically no long-term effect on prices, and shortages were only temporary — essentially an ineffectual policy. But note that Aparicio and Cavallo’s analysis ends in 2015! A couple of years later, Argentina experienced soaring inflation:

It’s possible that the rebound inflation from the lifting of temporary price controls touched off this big inflation in the late 2010s. Note that inflation is actually a big danger of price controls, since the threat of shortages can lead to hoarding of food and consumer goods, which exacerbates shortages and drives up prices even more.

What about Nixon’s price controls in the 1970s? Blinder and Newton (1981) argue that these controls had a very small and ultimately temporary effect on prices — similar to what Aparicio and Cavallo found for Argentina. And they argue that the “rebound” from the end of temporary price controls exacerbated the inflation of the late 1970s.

So it seems like the best result America could hope for from a regime of grocery price controls is “nothing”, and the worst result is very very, very bad. In between lies a range of moderately bad outcomes.

This is the same argument I made back in 2022 when Elizabeth Warren was trying to pass a bill to limit “gouging”. Fortunately, the Biden administration resisted the temptation to sign on to the price-control push, instead choosing to simply yell at companies for charging too much. Instead, Biden and his team focused on A) measures to boost supply through government action, such as the IRA, and B) antitrust.

That was the right approach. Progressive economics has sort of a “light side” and a “dark side”. The light side is industrialism, which wants to build more supply, and which recognizes that government is an essential tool in that effort. The dark side is a sort of left-populism that blames the machinations of greedy corporations and billionaires for every economic challenge, and which believes that limiting corporate profits will somehow trickle down into improved fortunes for the middle and working class.

The dark populist flavor of progressive economics is what Joe Stiglitz embraced when he traveled to Venezuela in 2007 and effusively praised Hugo Chavez’ economic policies (Stiglitz also suggested price controls on gasoline in the U.S. in 2022). It’s what Elizabeth Warren embraced in her call for price controls in 2022. And it’s the branch of progressivism that is informing Kamala Harris’ decision to make price controls her first big economic policy proposal.

This is a big misstep. Under Biden, Democrats came up with a version of progressive industrialism that promised to remake the U.S. economy while avoiding most of the mistakes that command-and-control policies made in the 20th century. With inflation now down, the economy strong, wages growing, and factories finally being built on American shores, there is no reason for Harris to execute a hard pivot to left-populism just to differentiate herself from Biden. On housing, for example, Harris’ proposal is strong — and very Bidenesque. Promising to stay the course toward abundance, reindustrialization, wage growth, and antitrust would be consistent with the sunny vibes that have buoyed her campaign thus far.

Update: The Harris campaign appears to be toning down the rhetoric on price controls pretty quickly, telling some people that the proposal is just about increasing antitrust enforcement. That’s a very good sign. It shows that the Harris campaign, unlike the Trump campaign, listens to reason.

Update 2: Harris has now clarified that she doesn’t support Elizabeth Warren’s “anti-price-gouging” bill, and that her efforts to combat “price gouging” wouldn’t extend past grocery stores. I see this as a sign of a significant walk-back, and a sign that we don’t have to worry about a price control regime. Unlike the GOP, the Dems listen to reason when they make a misstep.

I hope this isn't a misstep, but rather a good political calculation that recognizes that whatever the truth is, there is a massive PERCEPTION problem out there about the reality of the economy, largely fueled by right-wing BS media that says the economy has never been worse.

American voters really don't care about charts or policy details -- I don't mean this as a criticism, just a fact, people are busy. They care about results. Like with healthcare, they care about whether they can see their doctor when they need to, get surgery when they need it, and will it bankrupt them?

Likewise here. I tend to agree with other commenters who think this is more about messaging. A lot of Americans have the populism bug, and they just need to feel like whoever is at the top gives a shit about what they're going through. I think (I hope) this is a chance for her to say "No matter what the fancy experts say, I know many of you are hurting, and I'm going to go to bat for you."

We'll have to see what she says and actually proposes. Obviously the entire Right is ready to scream "COMMUNIST PRICE CONTROLS!" and I'd hate to think the Harris campaign just handed them that on a silver platter.

I read that Harris statement, and I think you are taking it many miles too far.

"Price gouging" leaves her a ton of weasel room. (Especially now when inflation has fallen off.)

The play here is entirely political. When bad things happen, human beings need a scapegoat.

Over the years, prices went way up on stuff like health care and college and real estate. While income remained fairly flat for most people. But at least, inflation on everyday stuff remained low. Then post pandemic income finally went up, particularly for the less affluent half of the population, but damn it, price increases on things like food and gas consumed a huge portion of that increase. People were pissed, and since dimming rates of inflation do not mean falling prices, they are going to be pissed for some time.

Republicans offer a scapegoat: the Biden administration.

Harris's job is to deflect that. The political loser answer, which I expected from Democrats, is a technical response about all those pay raises adding to the cost of things, and Trump's part in Covid relief legislation, and (especially) how pay raises have kept ahead of inflation. Regardless of the merits, none of this would move the needle an iota.

The political winner is to offer a better scapegoat than that offered by the Republicans. Something easier to understand. Easier to act on. So... prices went up due to price gouging, and we will forbid it. (After you make me president, and send Donald Trump into retirement.)

Note that she did not say that she is going to limit the price increase on milk and eggs and bread to a specific government-determined number. Rather, after she takes the oath of office, she would be looking at particularly egregious cases of price gouging. You can bet she will take action cautiously, because odds are great that the process will not go quickly and the courts will take a dim view.

The road from this to price controls... I'm not seeing it in my worst nightmares. Simply will not happen.