How Maduro and Chavez wrecked Venezuela's economy

What *not* to do when you're in charge of a country.

Venezuela just had an election. The country’s long-ruling president, Nicolas Maduro, declared himself the winner, but he’s widely believed to have rigged the results, and the opposition claims to have won a decisive majority of the actual vote. Only a few countries have recognized Maduro’s win, and the list isn’t an encouraging one — China, Russia, Iran, North Korea, Syria, Cuba, Nicaragua, Honduras, and Bolivia.1 Most Latin American leaders — including many associated with the political Left, in Chile, Brazil, Mexico, Colombia, etc. — have withheld their approval, demanding to see better evidence of the vote count.

Venezuela’s people, angry over the apparently stolen election, have taken to the streets, and a few people have died so far. There are dramatic scenes of bakeries sharing free bread in solidarity with the crowds, and so on.

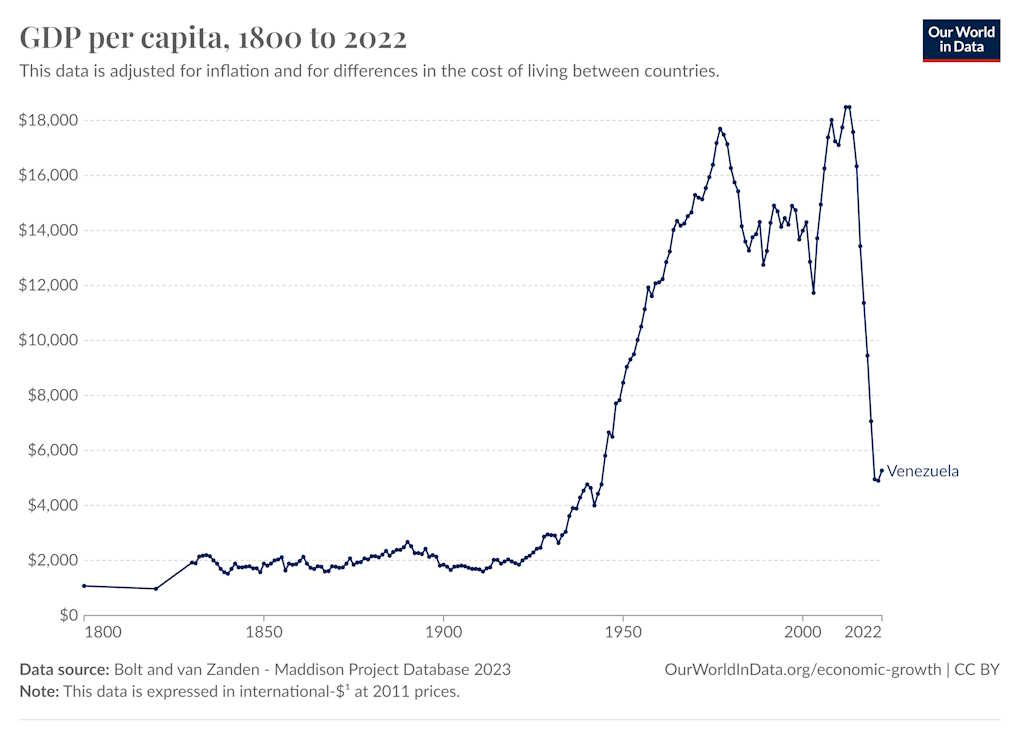

Why is Maduro so unpopular? Obviously a big part of it is that he’s an authoritarian who rigs elections and turns government force on protesters. But the even deeper reason is that on his watch, Venezuela suffered the kind of catastrophic economic collapse that usually only happens to countries in the grips of war. The Venezuelan economy is so bad (and the government so secretive) that the World Bank doesn’t even have estimates for the country’s GDP numbers. But the people at the Maddison Project estimate that Venezuelan living standards are now as low as they’ve been since World War 2:

If you want an idea of what this collapse has meant in terms of human suffering, I recommend Bloomberg’s series of reports from Venezuela in 2021. If I were a citizen of Venezuela, I would be mad too.

How did the country come to this sad juncture? A lot of people simply wave their hand and say “Socialism always fails.” Maduro and his predecessor Hugo Chavez brand themselves as champions of socialism, so it’s tempting to lump their failure in with the failures of countries like the Soviet Union and North Korea.

But that’s too simplistic of an answer. On one hand, as I’ll argue later, Venezuela’s failures do have a lot to do with ham-handed government interventions like expropriation and price controls. But not all “socialist” systems are created equal. Venezuela doesn’t have a central planning regime like North Korea or the old USSR. And none of the other “socialist” countries in Latin America — including Maduro’s political allies in Bolivia, Nicaragua, and Cuba — have suffered anything like what Venezuela has:

To wave away Venezuela’s collapse as a function of “socialism” thus ignores the interesting details of exactly which policies Maduro and Chavez used to bring down their country.

I should also mention that a far less credible explanation is to blame “capitalism”, as some New York Times reporters hilariously tried to do in a recent article:

Founded by former President Hugo Chávez, Mr. Maduro’s mentor, the [Venezuelan socialist] movement initially promised to lift millions out of poverty…For a time it did. But in recent years, the socialist model has given way to brutal capitalism, economists say, with a small state-connected minority controlling much of the nation’s wealth.

This is just totally absurd. The fact that the New York Times published this is probably a reflection of the ongoing internal cultural problems at the paper. As Alex Tabarrok notes, the “brutal capitalism” that the Times reporters refer to means the lifting of some price controls and the legalization of remittances from the United States. Those were good measures, and have done a little bit to help ease the pain of Venezuela’s citizens. The collapse happened years earlier.

So what did destroy Venezuela’s economy? Basically, I think it was a combination of three things:

Interfering with the efficient operation of Venezuela’s state-owned oil company, PDVSA

Expropriating and nationalizing large numbers of private businesses

Responding to inflation with price controls

But before I get to these, let’s dispense with the idea that U.S. sanctions are what brought Venezuela down.

The Venezuelan economy was dying well before U.S. sanctions

Maduro’s allies and apologists, as well as America’s critics, love to claim that American sanctions are responsible for Venezuela’s collapse. This claim often makes it into the American press — for example, a recent feature in the Washington Post claimed that “sanctions on Venezuela…contributed to an economic contraction roughly three times as large as that caused by the Great Depression in the United States.”

Perhaps the most respectable figure associated with this viewpoint is the Venezuelan economist Francisco Rodriguez, who served as an advisor to the Venezuelan government and now teaches in the U.S. He has written several reports — one in 2022, and one in 2023 for the Center for Economic and Policy Research — claiming that U.S. financial sanctions decimated Venezuela’s oil industry and caused the country’s economic collapse. This is from his CEPR report:

Economic sanctions were first imposed on Venezuela in 2017, when the Trump administration barred financing and dividend payments to Venezuela’s government and state-owned oil company. Though restrictions on some state activities go back to 2005, and personal sanctions on some government officials go back to 2008, none of these were on a scale that was large or systematic enough in our view to significantly affect the functioning of the Venezuelan economy until at least early 2017…

On August 24, 2017, President Trump issued an executive order prohibiting the purchase of new debt issued by the Government of Venezuela or [the state-owned oil company] PDVSA, and that of previously issued debt held directly or indirectly by the Venezuelan government. It also barred dividend payments to Venezuela, impeding the government from using profits from its offshore subsidiaries to fund its budget. Exceptions were built in for short-term commercial debt, winding down of existing contracts, and transactions related to the financing of purchases of agricultural commodities or medical goods from the United States.

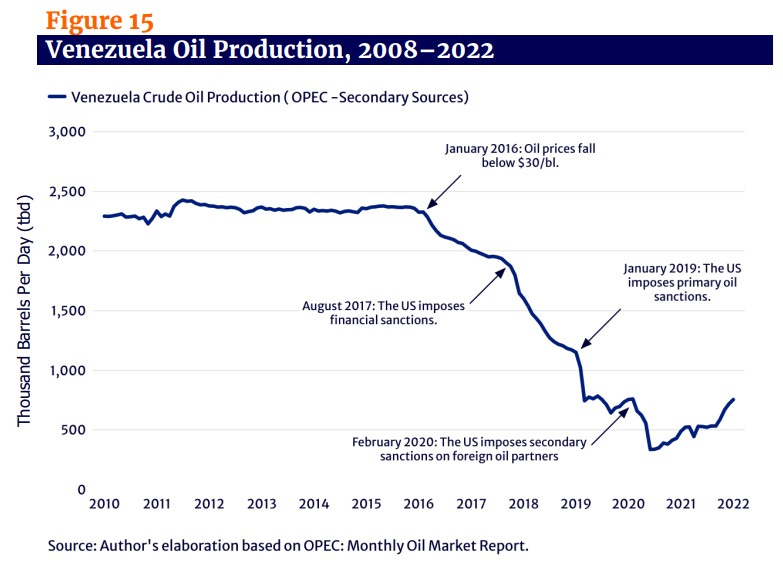

He claims that the 2017 sanctions caused a catastrophic collapse in oil production:

This is the strongest, most plausible case you can make for sanctions being the prime culprit. But the case still doesn’t really make sense, because the timing just doesn’t line up.

Although oil is an important piece of Venezuela’s economy, ultimately it’s just one input. The proximate causes of Venezuela’s immiseration are a currency crisis and hyperinflation. Both of these began long before 2017.

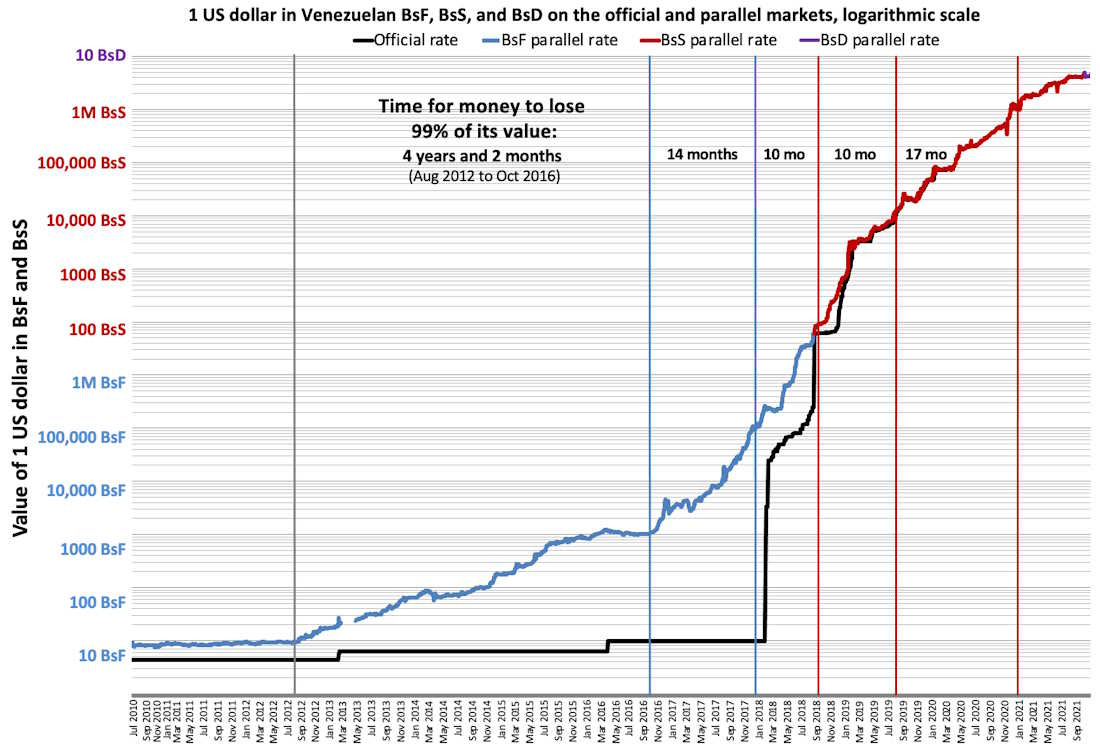

First, let’s talk about the currency crisis. Remember that most countries need foreign currency to buy imports. If the value of the currency crashes, consumers stop being able to afford everyday goods. The Venezuelan currency, the bolivar, was officially devalued in 2018. But if you look at the black market — which is where Venezuelans actually trade bolivars for dollars — the Venezuelan currency began to crash in the middle of 2012, losing 90% of its value against the dollar by September 2016:

That happened well before sanctions. Incidentally, it also happened two years before oil prices fell in 2014 — another external factor that Maduro/Chavez apologists used to blame.

Rodriguez completely ignores the effects of this pre-sanctions currency collapse in driving PDVSA to ruin. Remember, when a country’s currency collapses, it becomes much harder to pay debt denominated in foreign currency. PDVSA had done quite a bit of this sort of borrowing, so it was already preparing to default well before 2017.

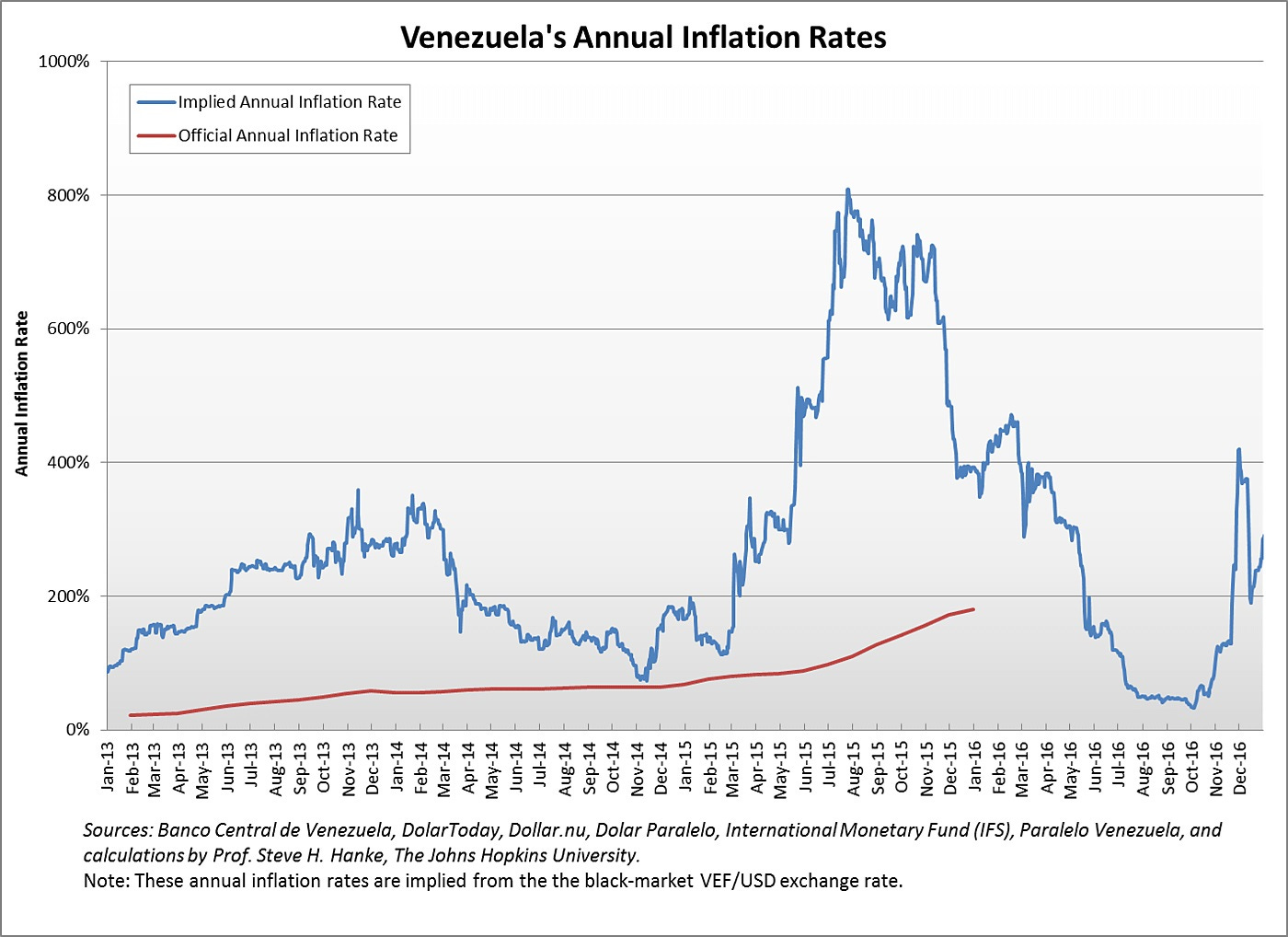

Along with currency collapse came hyperinflation. Official statistics show inflation rising gradually, to 200% by the start of 2016. Independent estimates show it significantly higher, a lot earlier:

Currency collapse and hyperinflation led to a collapse in Venezuelans’ ability to afford the basic daily necessities of life. Venezuelans were found to have lost an average of 8 kilograms (17.6 pounds) in 2016, due to an inability to afford food. Here are excerpts from an article in the Atlantic by Moises Naim and Quico Toro from May 12, 2016:

In the last two years Venezuela has experienced the kind of implosion that hardly ever occurs in a middle-income country like it outside of war. Mortality rates are skyrocketing; one public service after another is collapsing; triple-digit inflation has left more than 70 percent of the population in poverty; an unmanageable crime wave keeps people locked indoors at night; shoppers have to stand in line for hours to buy food; babies die in large numbers for lack of simple, inexpensive medicines and equipment in hospitals, as do the elderly and those suffering from chronic illnesses.

It’s not hard to find reports from other news outlets from 2016 (or even earlier) reporting the exact same thing. Venezuela’s hyperinflation, its currency crisis, and its collapse in living standards were all widely reported common knowledge well before the sanctions that Francisco Rodriguez blames.

It’s also worth comparing Venezuela to Iran, another oil-dependent country that was under far more stringent U.S. sanctions in the 2010s. Iran stagnated under those sanctions, and also suffered from the oil price drop in 2014, but its economy didn’t even come close to collapsing:

Now, there’s still a possibility that the sanctions of 2017 made Venezuela’s situation worse. Inflation and currency depreciation both accelerated in 2017 and 2018. Kicking Venezuela’s economy when it was down was a policy mistake on the part of the Trump administration. But make no mistake — the Venezuelan economy was already down when Trump started kicking it.

So what did Venezuela’s leaders do to impoverish their nation? It’s hard to determine causality for sure, but three bad policies of the Chavez-Maduro era stand out: mismanagement of the state-owned oil company, expropriation of private business, and price controls.

Mismanagement of the state-owned oil company

Venezuela is a petrostate, meaning that it depends heavily on crude oil for both export earnings and for government revenue. But not all petrostates are created equal. Although on paper Venezuela has the world’s largest proven oil reserves, most of this is “heavy” oil, which is a lot harder to extract. Venezuela’s oil also has lots of impurities like sulfur, which make it hard to process. This means that it takes a lot more investment to sustain Venezuela’s oil industry than, say, Saudi Arabia or Iran.

Fortunately for Venezuela, it got that needed investment for a long time, thanks to its far-sighted and competent state-owned oil company, PDVSA (pronounced “peh-deh-VAY-suh”). Created in the 1970s, PDVSA hired the best and the brightest, and the government largely left it alone to do its thing.

But in the late 90s and early 2000s, Venezuelan leaders began to raid PDVSA’s investment budget. Chavez accelerated this extraction in order to fund his social programs (and, undoubtedly, payments to various regime cronies as well). This made it impossible for PDVSA to keep up the investment needed to increase oil production — or, eventually, even to maintain it. The technocrats at PDVSA protested this move, and he fired them en masse. The Economist told the tale back in 2006:

PDVSA developed a reputation for professionalism and competence…The company was thought to be relatively free from…corruption and cronyism…It was certainly efficient, producing as much oil as [Mexico’s] Pemex did with a third of the staff…[But] with an election looming [in 1998], the government slashed the company's investment budget…

Venezuela's fields require a lot of maintenance. The oil they produce is more viscous and acidic than the norm…Less than a tenth of the fields simply spout oil thanks to the natural pressure of the reservoir. Keeping the remainder flowing requires constant injections of water or gas. Even so, their output declines at roughly twice the pace of oilfields in the North Sea. Venezuela has to add 400,000 b/d of new annual production capacity just to keep output stable…That is even more expensive than it sounds, because each well produces only a small amount: perhaps 180 b/d, compared with as much as 7,000 b/d from some Persian Gulf wells. It takes Venezuela ten times more wells than Saudi Arabia to produce a third of the oil. No wonder that at the height of its expansion in 1997, PDVSA was investing $5.4 billion…

[W]hen President Hugo Chávez came to power in 1999, he started squeezing even more money out of the firm. By 2000 investment had fallen to $2.5 billion. Mr Chávez accused PDVSA of hiding its profits from the government through deceptive accounting. He also questioned the firm's expansion plans and overseas acquisitions. Above all, he decried its relative autonomy and appointed a number of hostile bosses to impose his authority.

PDVSA's management, naturally, resented this. They joined a general strike in December 2002, along with half of the firm's 40,000 employees. Most of the skilled staff, including engineers and technicians, stopped work for two months. Since…many of PDVSA's wells require constant monitoring and treatment…the strike killed lots of them. Analysts estimated that Venezuela lost as much as 400,000 b/d of production capacity…But the worst was still to come. Mr Chávez denounced the strikers as saboteurs and sacked them all. The toll was highest among skilled workers: two-thirds of managers and technical staff went. At a stroke, PDVSA lost almost all of its most experienced and best-qualified employees…

Critics say that the government restaffed the firm with incompetent cronies…. Contractors whisper that it is having trouble spending even its reduced investment budget…The company can no longer maintain its own fields, let alone complete the many new projects it is pursuing[.]

Other sources tell similar stories.

Chavez and his cronies seemed to simply not understand the technical details of Venezuela’s oil industry — they thought Venezuela was Saudi Arabia, and they fired anyone who was willing to stand up and tell them otherwise. As a result, Venezuela’s oil production stagnated and began to fall. But its net oil exports suffered even more, because it had to import light sweet crude to mix with its own oil. This is from 2014:

As weird as it seems, Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro’s government plans to start importing crude oil for the first time in order to blend it with Venezuela’s own crude and keep the country’s overall production from falling further. It turns out that Venezuela’s own production of light crude oil has plummeted since the late President Hugo Chávez took office in 1999, and the country desperately needs light crude oil to blend with its Orinoco Basin extra heavy crude oils. Without such a blend, the Orinoco Basin’s extra heavy crude is too dense to be transported through pipelines to Venezuelan ports and exported abroad…Production of light crudes has fallen because of lack of investments, abandonment of exploration of light crude areas, and the nationalization of companies that used to help produce light crudes. So, while the government has already been buying refined products to blend with its heavy crudes, it will now be forced to import light crude oil[.]

As a result, even though Venezuela was still selling plenty of oil abroad, the country’s net oil exports began to crash early in Chavez’ tenure:

For a while, this seemed not to matter. Oil prices soared in the 2000s, so despite the drop in net exports, the money kept rolling in to government coffers. And the oil price spike kept investment from falling off a cliff, despite Chavez’ raids on PDVSA’s budget.

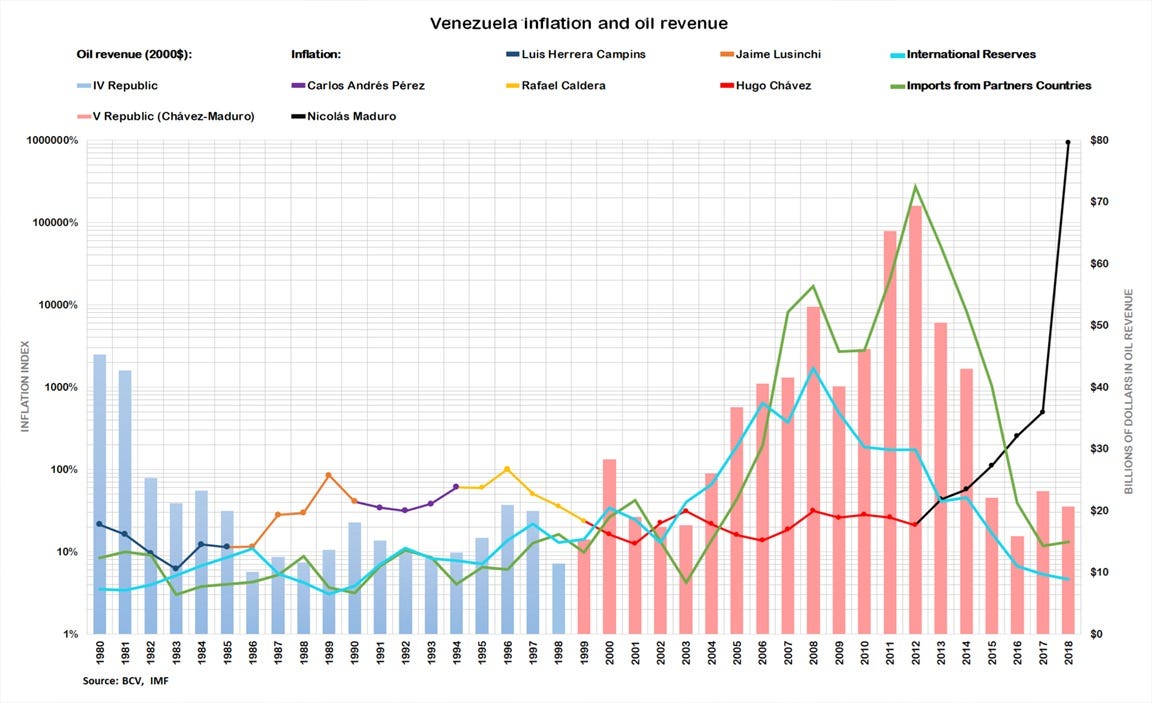

But Chavez’ mismanagement of PDVSA was setting the country up for total disaster. When oil prices fell in 2014 (shortly after Chavez died and Maduro took over), PDVSA’s chronic lack of investment under Chavez and Maduro began to tell. Production began to fall steeply, and the government’s oil revenues — the pink bars on the graph below — fell off a cliff:

This was all well before sanctions hit, and it coincides with the start of Venezuela’s currency collapse and entry into hyperinflation.

Thus, one of the biggest causes of Venezuela’s collapse was Hugo Chavez’ mismanagement of PDVSA. What kind of “socialist” cripples the state-owned oil company and fires half of its workers for striking? Not a very smart one, I’d say.

At the same time, though, Chavez was doing some genuinely destructive socialist things regarding other sectors of the economy.

Expropriation and nationalization

Hugo Chavez was extremely hostile to private business. This is from ABC News in 2013:

The Chavez government has expropriated or nationalized numerous companies (no one seems to be able to count them all) involved in various sectors including aluminum, cement, gold, iron, steel, farming, transportation, electricity, food production, banking, paper and the media. The number of private companies in industry has dropped from 14,000 in 1998 to only 9,000 in 2011, according to [economist Gerver] Torres.

Many self-described socialist leaders nationalize national resource companies and infrastructure like transportation, electricity, and telecoms. But Chavez went after a much broader swathe of the Venezuelan economy — supermarkets, housing, agriculture, finance, steel, tourism, glass, cement, etc. Overall, over a thousand companies were nationalized between 2003 and 2012.

The Manhattan Institute documented some of the inevitable failures that occurred when Chavez’ cronies started attempting to run these companies as engines of redistribution:

[A]s state control of the agricultural industry increased, Venezuela’s food production fell 75% in two decades while the country’s population increased by 33%….After agriculture, the regime nationalized electricity, water, oil, banks, supermarkets, construction, and other crucial sectors. And in all these sectors, the government increased payrolls and gave away products at low cost, resulting in days-long countrywide blackouts, frequent water service interruptions, falling oil production, and bankrupt government enterprises.

It seems likely that as with the oil industry, cronyism was also involved.

This sort of nationalization harms the economy in several ways. First, government is often not very good at running things like supermarkets and cement factories. Second, Chavez appears to have taken a similar approach with these newly nationalized industries that he did with the already-nationalized PDVSA, using them as piggy banks for social programs. This led to short-term poverty reduction, but in the long run it killed the goose.

And third, arbitrary nationalization of private companies is a huge disincentive to private investment. If you’re a businessperson, why would you start a business when the government is likely to just swoop in and take it away at any moment (at a price of the government’s own choosing)?2

As a result, despite Venezuela’s incredibly crashing currency (which makes exports cheaper), the country’s non-oil exports began to plummet in the 2000s:

Chavez’ expropriations — and Maduro’s — turned Venezuela into more and more of a petrostate over time. When mismanagement of PDVSA and falling oil prices hurt the oil industry, the country had nothing else to fall back on. The disaster of the 2010s had its seeds in the 2000s.

As an aside, it’s also worth noting that Maduro hasn’t just expropriated capital — he’s also expropriated labor, by forcibly drafting workers into food production. This is from 2016:

The government of president Nicolás Maduro has, in a new decree, paved the way for the conscription of the nation’s citizens into forced labor…The decree “establishes that people working in public and private companies can be called upon to join state-sponsored organizations specializ[ing] in the production of food,” explained Amnesty International last week. “They will be made to work in the new companies temporarily for a minimum of 60 days after which their ‘contracts’ will be automatically renewed for an extra 60-day period or they will be allowed to go back to their original jobs.”…“Trying to tackle Venezuela’s severe food shortages by forcing people to work the fields is like trying to fix a broken leg with a Band-Aid,” said Erika Guevara Rosas, Americas Director at Amnesty International.

This was probably the closest thing to old Soviet communism that Maduro or Chavez has actually tried.

Price controls

Nationalization of industry is the clearest case where you can point to the Chavez-Maduro regime and say “See? Socialism doesn’t work!”. But it isn’t the only one. Chavez and Maduro also made extensive use of another very destructive policy: price controls.

Hugo Chavez started to use price controls well before hyperinflation struck. It was another populist policy meant to provide cheap stuff to the poor. This very predictably led to shortages as early as the mid-2000s:

President Hugo Chavez's policy of keeping a tight control on food retail prices while doubling the price of raw coffee beans back in December may have backfired…For at least a week, there has been no roasted coffee available on the shelves of Venezuelan supermarkets as wholesalers and coffee producers have been withholding their coffee from sale…Since 2003, President Chavez has maintained a strict price regime on some basic foods like coffee, beans, sugar and powdered milk…But this measure designed to curb inflation has alienated Venezuela's coffee producers who say their profit margins have been reduced to nothing…

Venezuela's leftwing leader has authorised the use of the National Guard to "find every last kilogram of coffee" being stockpiled by coffee roasters…Yet several food stores in Venezuela's capital city Caracas say the coffee raids are not addressing the fact that shops are also running low on sugar, maize, powdered milk and beans…Store managers insist they are not being supplied with new stock from wholesalers and importers, who were also complaining that the prices set by the government are too low.

Price controls led to precautionary hoarding, despite Chavez’ attempts to impose harsh penalties on people stockpiling food and other consumer goods. That fueled higher inflation, even before Venezuela’s currency started collapsing in 2012. Chavez responded to the rising inflation in 2011 with — you guessed it — more price controls:

The prices of 18 products, including soap and shampoo, are being frozen with immediate effect while other sectors will be examined in the coming months…Firms, including multinationals like Colgate and Pepsi-Cola, will have to report production costs so officials can set what is deemed a fair price…President Hugo Chavez said the aim was to "protect people from capitalism"…Price controls were first introduced in 2003 and staples like cooking oil and rice are currently regulated…The law widens the number of goods being monitored, including fruit juice and mineral water, as well as cleaning products such as detergent…Toilet paper, toothpaste and disposable nappies are among toiletries and personal items on the price control list.

Then the bolivar collapsed, the price of imports soared, and inflation really took off. What do you think the Venezuelan government — now led by Maduro, after Chavez’ death — did about this? That’s right — even more price controls. This is from 2014:

Venezuela on Friday decreed a new price control law that sets limits on company profits and establishes prison terms for those charged with hoarding or over-charging, part of socialist President Nicolas Maduro's efforts to tame inflation…The law carries prison sentences of up to 14 years for crimes including hoarding, "destabilizing the economy" and food trafficking…Previous laws created by Chavez called for prison sentences of up to six years for hoarding or overpricing of food.

One important price control was on the currency itself. Starting around 2012, Venezuelans decided that they really wanted to get their money out of the country and exchange it for dollars. This caused the value of the bolivar to fall. Chavez and Maduro responded by pegging the exchange rate at a very high value — insisting that bolivars only be traded for dollars at a much more favorable price than the one the market was willing to pay. Venezuelans who wanted to get their money out responded by going to the black market.

Anyway, the Chavez/Maduro price controls led to a sort of crazy, pervasive regime of terror, with the government running around trying to find and punish anyone who had too much food or too many basic consumer goods. Here’s an anecdote from Moises Naim and Quico Toro from 2016:

When a Venezuelan entrepreneur we know launched a manufacturing company in western Venezuela two decades ago, he never imagined he’d one day find himself facing jail time over the toilet paper in the factory’s restrooms…

[A]mid deepening shortages of virtually all basic products (from rice and milk to deodorant and condoms) finding even one roll of toilet paper was nearly impossible in Venezuela—let alone finding enough for hundreds of workers…So the entrepreneur turned to the black market, where he found an apparent solution: a supplier able to deliver, all at once, enough TP to last a few months…

But the problem wasn’t solved.

No sooner had the TP delivery reached the factory than the secret police swept in. Seizing the toilet paper, they claimed they had busted a major hoarding operation, part of a U.S.-backed “economic war” the Maduro government holds responsible for creating Venezuela’s shortages in the first place. The entrepreneur and three of his top managers faced criminal prosecution and possible jail time.

Guess what? When you run an economy like this for decades, it’s not going to stay rich. (Remember this next time economists like Isabella Weber or the folks at the Roosevelt Institute tell you that price controls are the best medicine for inflation.)

So yes, Chavez and Maduro wrecked Venezuela’s economy with bad policy. The oil price drop of 2014 certainly didn’t help, nor did America’s sanctions in 2017. But the core screw-ups were mismanagement of PDVSA, nationalizations, and price controls. The first of these was questionably “socialist”, since it involved strike-breaking and weakening of a state-owned enterprise. But the second and third fall pretty clearly within the ambit of policies that 21st-century socialists tend to embrace. Other “socialist” countries in Latin America, such as Bolivia, have escaped Venezuela’s fate by doing less of all three of these things.3

Venezuela thus serves as a warning to other countries. Electing left-wing leaders can be fine — witness Boric in Chile, Lula in Brazil, etc. But you really do have to watch out for the Chavez/Maduro types who think that “revolution” means taking a wrecking ball to every economic institution in the country. That way lies madness.

Once again, much of what you see in the news is part of Cold War 2. Maduro is getting support from China and its various proxies because he’s perceived to be a thorn in America’s side.

Predictably, antisemitism was also a factor here.

Cuba is the exception, having nationalized most of its economy long ago, and not being dependent on natural resources. That has left it poor and stagnant, but it has managed to have only minor crises so far.

I’m Venezuelan, attended university in USA and have worked as an Economist, so this issue is close to my heart.

There are so many examples of destructive behavior by the Chavez/Maduro government that it is difficult to begin describing them all. But you have made a good start.

It is worth mentioning the opaque funds started by Chavez, for example the $100 Billion FONDEN fund from the proceeds from international oil sales above the national budget’s reference price. These funds had zero oversight; nobody knows what happened to that money. Over a Trillion dollars in oil exports were received during 25 years of the Chavez/Maduro era, and what remains is an ash heap with a $154 Billion mortgage.

Oil money was used to buy loyalties within and outside the country, just look at yesterday’s shameful failure by the Organization of American States to even initiate an impartial probe into Venezuela’s July 28 election. The 35-member OAS needed 18 votes to pass the motion but only mustered 17 votes.

It has been credibly argued that Venezuela’s point of no return was the 2004 packing of Venezuela’s Supreme Court by Hugo Chavez: https://www.caracaschronicles.com/2009/04/27/thoughts-on-the-eve-of-the-fifth-anniversary-of-1m/

I always find it strange when leftists blame American sanctions for economic troubles in "socialist" countries. Do their economic darlings have to suck on the American capitalist teat to function? Can't they turn to the many other friendly countries instead?