Is economics an excuse for inaction?

No, it is not. But there's a reason people think it is.

Statistics PhD student Kareem Carr asked a provocative question the other day on Twitter:

The question provoked a lively thread of responses and discussions (which usually manages to avoid descending into the typical Twitter shit-show of shouting and bad faith). But I thought it was interesting enough to write a post about.

Is the goal of economics to provide supporting arguments for the inaction of the ruling class? Is the meme at the top of this post accurate?

Well, no, it’s not. The people who do academic economics generally do not have this goal. The body of theory and empirical work that comprises modern economics was generally not written with this goal in mind. Carr’s notion is a popular fantasy, promoted by some people on the political Left (who want it to be true so they can bash economics) and some on the political Right (who want it to be true so they can appropriate the prestige of the field for their own ends).

But this popular fantasy does have its roots in some real things, so I thought it would be good to discuss why this misconception is so popular and enduring — and why it’s wrong.

Econ’s roots

There’s a sort of popular myth that economics began with Adam Smith’s declaration that the “invisible hand” of the market would lead to a good society. In fact, while Smith did recognize the importance of market forces and self-interest, his vision of a good society didn’t stop there. Here are some Adam Smith quotes:

“Our merchants and masters complain much of the bad effects of high wages in raising the price and lessening the sale of goods. They say nothing concerning the bad effects of high profits. They are silent with regard to the pernicious effects of their own gains.”

“It is not very unreasonable that the rich should contribute to the public expense, not only in proportion to their revenue, but something more than in that proportion.”

“No society can surely be flourishing and happy of which by far the greater part of the numbers are poor and miserable.”

“Wherever there is great property there is great inequality. For one very rich man there must be at least five hundred poor, and the affluence of the few supposes the indigence of the many.”

“People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices.”

And so on. Adam Smith decries the existence of inequality and poverty, blames property rights for this inequality, advocates progressive taxation as a remedy, and is innately suspicious of profit. He sounds more like Thomas Piketty than Milton Friedman.

Smith’s suspicion of profit and enthusiasm for redistribution are baked into the very core of economic theory. The zero-profit condition says that in a well-functioning market, the rate of profit should be no more than the cost of capital — if you see companies making big margins, you should suspect that the market isn’t working right. This is the basis of the antitrust movement, which is again gaining strength in America with the appointment of Lina Khan to chair the FTC. Though there are a few populist firebrands in the antitrust movement, much of it is an intellectual movement driven by economists.

Meanwhile, Smith’s call for redistribution is inherent in the Second Welfare Theorem, considered one of the basic theorems of economics — and something that every intro student is taught. The Second Welfare Theorem says that if you change the initial distribution of wealth in society, you can basically get any outcome you like. This puts the burden of proof on those who think we shouldn’t redistribute wealth — it forces them to bring proof that the harms from taxation are just too high. Though there have been some economists who opposed redistribution, enthusiasm for the idea is traditionally very dominant within the profession. Even Milton Friedman, that great champion of laissez-faire, supported the idea of a negative income tax that would give people more cash the poorer they were.

And though economists do generally believe that very high taxes have some costs, a 2013 survey found that 97% of economists favored federal tax hikes, compared to only two-thirds of the general public, and a 2020 survey finds that most economists think raising the top marginal rate wouldn’t hurt economic growth.

Over the decades, leading economists found other reasons for government intervention in the economy. Just a few examples:

John Maynard Keynes, the father of modern macroeconomics and an incredibly influential figure, came up with the idea of fiscal stimulus to solve the problem of recessions — an idea that is almost universally accepted today among economists.

Paul Samuelson, arguably the most influential economist of the 20th century, and the author of much of the modern economics curriculum, came up with the theory of public goods — things like infrastructure and research and public parks that the private sector won’t provide on its own.

Kenneth Arrow, one of the profession’s leading lights, explained why the free market doesn’t work in the health care industry.

Joseph Stiglitz, yet another Nobel prize winner, showed that under some simple assumptions, land should be taxed at 100% of its value — basically, total redistribution of the wealth from land ownership (the idea was originally due to the 19th century economist Henry George).

Along with George Akerlof, Michael Spence, and others, Stiglitz pioneered the theory of asymmetric information, which shows yet another reason free markets break down (and which provides another justification for government health insurance).

This is by no means an exhaustive list. But it shows how economists at the very top of the field — the people cited are not just Nobel winners but legendary names within the profession — spent their effort finding reasons to justify action by the ruling class to alleviate inequality, poverty, and market breakdown.

Now, you might ask — and many leftists do ask! — why such justification was even necessary in the first place. Why didn’t economists simply assume that government action was good and necessary? Why did they start with “free markets are good” as the baseline assumption, and then force themselves to work to find reasons markets break down?

And the answer is: They didn’t. While all of these economists recognized the importance of market forces in the economy, none of them started from the assumption that laissez-faire was good. But assuming that some kind of government action is necessary doesn’t imply that all government action is good — indeed, this is a common logical fallacy. You still have to figure out which kind of government intervention you need. And that’s what these economists were trying to do!

As an analogy, think about public health specialists. Just as Adam Smith recognized that poverty and inequality are the natural state of a market economy, public health people realize that people naturally get sick, and look for ways to prevent them from getting sick. Eventually they find that things like hand-washing and water sanitation are very effective in preventing illness. They didn’t start from the assumption that public health interventions are bad — they just had to figure out which interventions are good.

The free-market revolt

Now, the profession isn’t unanimous in its embrace of government intervention. There have always been at least a few economists who argued against things like progressive taxation, fiscal stimulus, welfare, government provision of health insurance, and so on. At certain times there have been a lot of these folks, and at times they have become very strong within the profession. The early years of the 20th century (the first Gilded Age) were one such time, until the Depression swept away the idea that the government should be a passive bystander. In the 1970s and 1980s, laissez-faire came back into vogue.

The libertarian economics of the 70s and 80s had its roots in the Mont Pelerin Society and the University of Chicago economics department in the mid 20th century. Economists like Friedrich Hayek, Milton Friedman, and George Stigler were consciously and openly ideological in their promotion of small-government ideology. This culminated in Friedman’s famous 1980 television special, Free to Choose, in which he combined libertarian principles with (often simplistic and obsolete) economic theory to endorse laissez-faire approaches across a broad swath of policy issues. This obviously dovetailed quite strongly with the Reagan and Thatcher revolutions in the political arena.

I don’t have evidence, but from talking to older economists, it seems like this free-market revolt drew a bunch of political conservatives into the economics profession in the 70s and 80s. At a time when academia in general was moving strongly to the left, econ seemed to some aspiring young people to be the “conservative science”. You can see the remnant of this in the political affiliations of the profession today — econ has only a 5.5-to-1 ratio of Democrats to Republicans, compared to a 43.8-to-1 ratio in sociology and an 8.1-to-1 ratio in political science! (Note: Some questioned this source for political affiliation; this 2006 paper by Klein and Stern shows a 2.5-to-1 ratio for economists, and this 2016 study by Langbert et al. finds 4.5-to-1 for economists, compared to 11.5-to-1 for social scientists in general. Here’s similar evidence from political donations.)

In any case, this free-market revolt left lasting marks on the profession. The new discipline of “law and economics” was dominated by the Chicago school, providing strong support to big business in its quest to become even bigger; now, some economists make big bucks moonlighting as expert witnesses helping corporations argue to courts that their mergers will increase economic efficiency (they usually don’t). The new antitrust movement is just beginning to successfully fight back.

And macroeconomics became temporarily dominated by anti-interventionists. Economists like Robert Lucas and Ed Prescott made models claiming that recessions are optimal economic outcomes (!!!), and that attempts to fight them only make things worse. These models did become the mathematical standard in macro, and though newer models do come up with good reasons to do fiscal stimulus, they were forced to work hard to do it — a rare case when the leftist critique of “non-intervention as a baseline” actually does actually bite.

Meanwhile, the free-marketers had a deep impact on econ education. Greg Mankiw’s textbooks, which generally favor free-market ideas, have become the standard introductory undergrad textbook, and are only now starting to be displaced by materials like Krugman’s textbooks and the CORE Project.

This free-market turn in the economics profession — which closely paralleled broader shifts in the political climate of the nation — is probably a big reason why many people now believe, as Carr does, that econ is a science dedicated to the ideological defense of government inaction. But it’s not the only reason.

Pop economism

It turns out that the “economics” most people interface with is not even mainstream academic economics. It’s a pop version of conservative ideology, broadcast by a network of well-funded partisan think tanks, right-leaning publications, and TV hucksters. So-called “supply-side economists” were often not even trained economists, but political columnists and commentators like Larry Kudlow and Jude Wanniski.

This process is well-described in James Kwak’s excellent book Economism: Bad Economics and the Rise of Inequality. I encourage you to read that book. What the various hucksters did was to describe their political positions using the language of economics, without much (any?) support from actual economics research. Academics who knew this was a lot of hot air tended to stay in the ivory tower, not speaking out. So the public’s perception of “economics” became dominated by the media motormouths.

Looking at where Carr is getting his impression of the econ profession, it turns out he’s getting it from…pop economics!

Now, to be fair, the Economist has moved strongly in a pro-government-intervention direction in recent years, and Russ Roberts has evolved in this direction as well. But when you’re getting your idea of what economics is from the pages of the Wall Street Journal, you’re not getting any sort of accurate picture of what economics actually says.

And that’s a problem.

Turning things around

In recent decades, three huge and important changes have happened in the economics profession. All of these changes work against both the free-market wave of the 70s and 80s and the rise of well-funded “economism” in the public sphere.

First, the profession has become much more empirical.

Whether or not something works in theory is less important now than whether it works in practice. Papers still have theory sections, but they’re more phenomenological — proposed explanations for observed phenomena, rather than a mathed-up form of philosophy. Meanwhile, new econometric methods relying on quasi-experiments are rapidly becoming dominant.

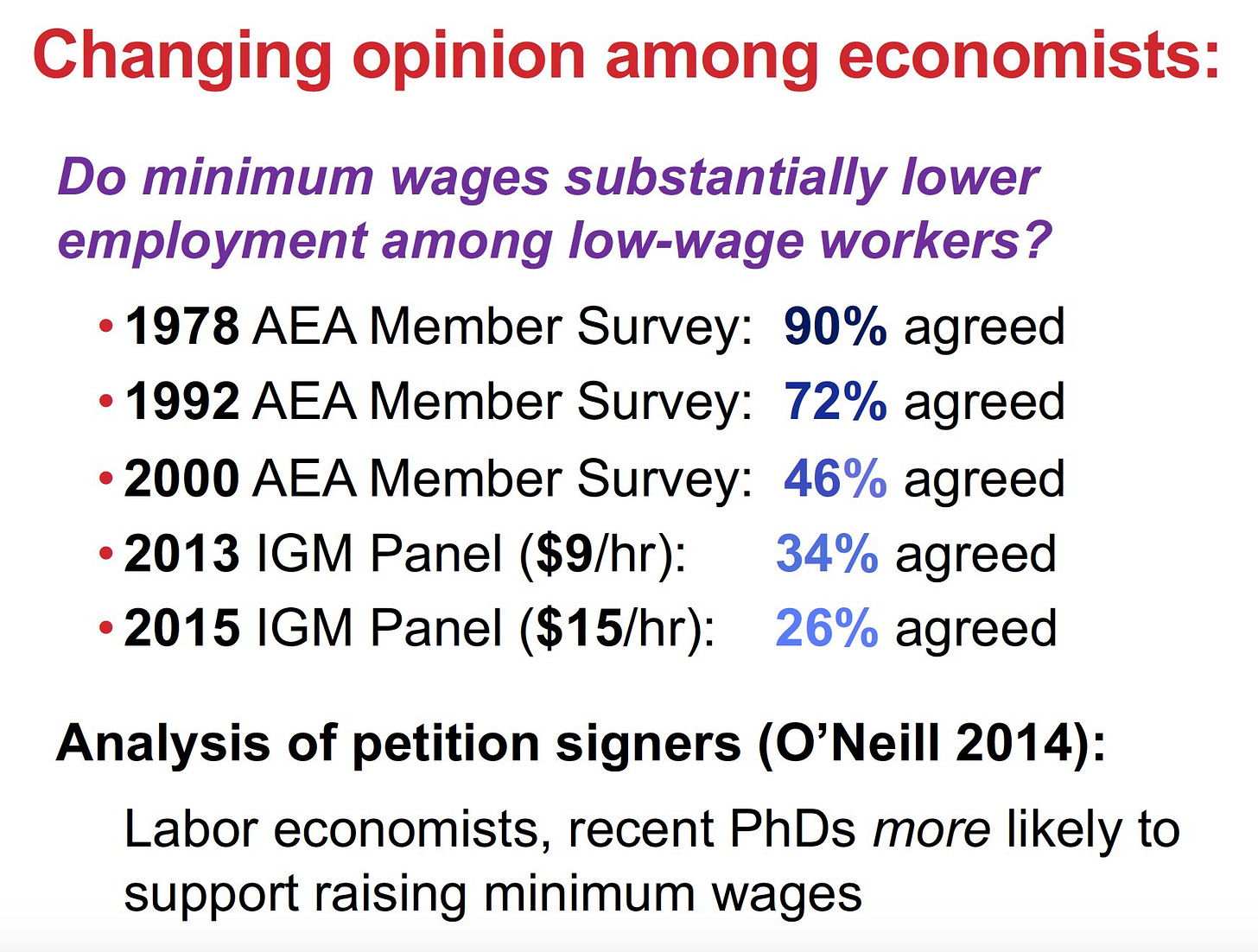

The empirical turn means that economists are more open to being persuaded by the evidence. Theory always supported the possibility that minimum wage would have a benign effect on employment (at least, up to a point). But a flood of increasingly credible empirical results has convinced economists to be much more favorable toward the minimum wage in recent years:

The second change was an increased willingness of academic economists to enter the public discussion. Leading media figures like Thomas Piketty, Paul Krugman, and Gabriel Zucman now lean to the left, and the influence of the generally left-leaning Econ Twitter is growing. Both of these help balance out the legacy institutions of the 80s free-market media machine.

But the third and most important change is in the econ profession itself. The free-market revolt is over. Economists’ concern about inequality is growing rapidly, as evidenced by the language economists are using in their papers. Here’s a graph of just one example:

It’s not just language, though. A large number of major research programs are now dedicated to finding ways that government can act to fix the economic problems besetting the U.S. and the world. Some of these include:

The study of inequality (and of taxation that could reverse it)

The study of labor market monopsony (corporate power that holds down wages)

The study of monopoly power and the new antitrust movement

The study of cash benefits

The Opportunity Insights program and parallel efforts to study and reverse falling mobility

Renewed interest in racial disparities

The new minimum wage literature

The new development economics

The new economics of poverty

…and so on.

Meanwhile, the institutions of the profession are becoming dominated by more and more intervention-minded scholars. For example, the last seven presidents of the all-important American Economic Association have been:

Richard Thaler, one of the inventors of behavioral economics

Robert J. Shiller, who wrote a book about how fraud and deception are fundamental to free markets

Alvin E. Roth, an economist who helped devise mechanisms of centralized allocation for things like organ transplants

Olivier Blanchard, a centrist macroeconomist who has been leaning more and more toward government intervention

David Card, who did the original research showing minimum wage isn’t so bad, and is one of the main champions of the empirical turn

Meanwhile, young high-profile economists tend to be champions of government intervention and foes of inequality.

This leftward shift of economic ideas parallels the overall leftward shift among the public — the age of Reagan and Thatcher is over, and the shortcomings of the free-market revolt have made themselves painfully apparent. Economists aren’t pushed around by popular opinion, but nor are they blind to events in the real world.

In any case, this hopefully clears up why Carr’s stereotype of the economics profession is — happily — a misconception. Econ did go through a phase where many of its most outspoken leaders and a coterie of loosely affiliated political pundits were dedicated to promoting the cause of government inaction. That phase has now been over for a while.

You write: "And so on. Adam Smith decries the existence of inequality and poverty, blames property rights for this inequality, advocates progressive taxation as a remedy, and is innately suspicious of profit."

Adam Smith did not advocate progressive taxation. His first maxim of taxation was:

"The subjects of every state ought to contribute towards the support of the government, as nearly as possible, in proportion to their respective abilities; that is, in proportion to the revenue which they respectively enjoy under the protection of the state. "

That's tax burden in proportion to income, or the equivalent of a flat tax.

Your number 2 point doesn't say it is a good thing to tax the rich more, it says that it is "not very unreasonable" — a bad thing, but not bad enough to block a tax that Smith thought desirable for other reasons.

Your quote 5 stops just before the point where Smith makes it clear that he is not supporting anti-trust policy, he is arguing against government policies that help create trusts, the 18th c. equivalent of the CAB cartelizing the airline industry. Here are the sentences you didn't give:

"It is impossible indeed to prevent such meetings, by any law which either could be executed, or would be consistent with liberty and justice. But though the law cannot hinder people of the same trade from sometimes assembling together, it ought to do nothing to facilitate such assemblies, much less to render them necessary."

Your quote 4 is again taken out of context, drastically changing its meaning. Here is what follows the bit you quote:

"The affluence of the rich excites the indignation of the poor, who are often both driven by want, and prompted by envy, to invade his possessions. It is only under the shelter of the civil magistrate that the owner of that valuable property, which is acquired by the labour of many years, or perhaps of many successive generations, can sleep a single night in security.

...Where there is no property, or at least none that exceeds the value of two or three days' labour, civil government is not so necessary.” He isn't arguing against inequality, he is saying that it is inequality that makes government necessary.

It's risky to pontificate on a book you haven't read, basing your views on other people's selected snippets. You are correct that Smith was not a conservative, but he was an 18th c. radical not a 21st century progressive, which is what you are trying to imagine him as. His basic view was that the laissez-faire policy he supported was in the interest of the laboring class.

I've discussed such misrepresentations of Smith repeatedly on my blog over the years as I encounter them.

Well, the academics might be moving on, but the GOP and conservative Dems are still using the 70s and 80s ideas as excuses for inaction. So in a sense he's right.