Why Everyone Loves Japan

Part III of my book on the Japanese economy.

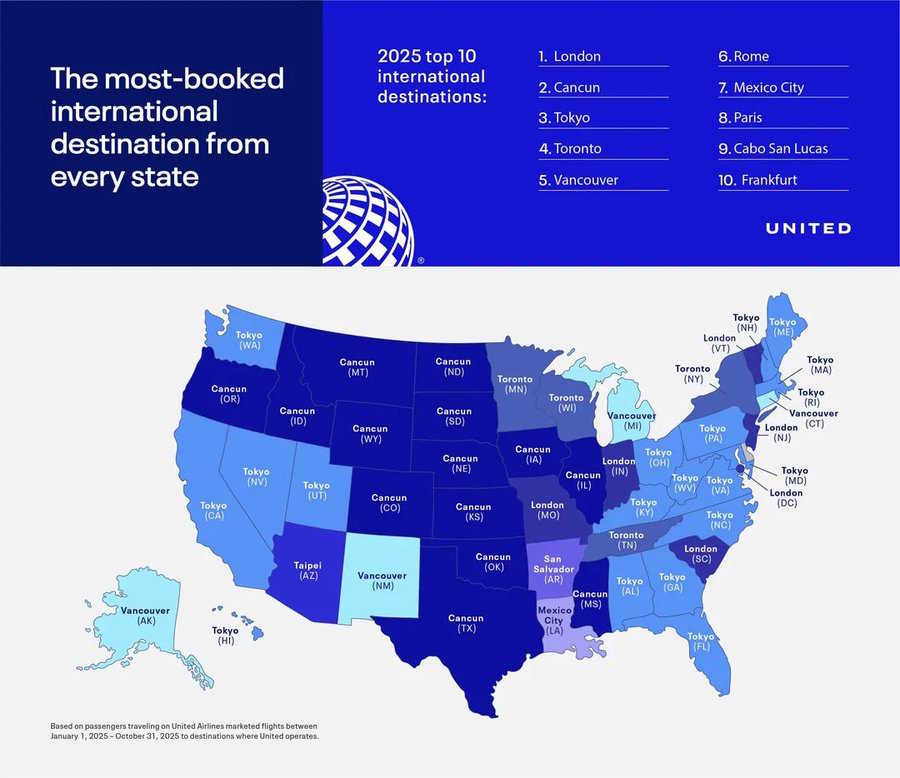

I hope everyone had a Merry Christmas! Winter holiday season is here, and for an increasing number of Americans, that means traveling abroad. Europe and Mexico are still hot destinations, but in recent years, Japan has skyrocketed to the top. In many places, Tokyo is the most-booked international flight destination:

Some of this is because of transfer flights to the rest of Asia, but most of it is just because practically everyone in America — and the world — at large wants to go to Japan these days. Every year, various friends text me requests for my Japan recommendations right around this time of year (I should really write a blog post summarizing these. I did one in the 2010s, but it’s totally out of date.) I myself will be there in early January.

Anyway, the fact that everyone is going to Japan right now provides a perfect opportunity for me to explain how the world’s love for Japan creates a key opportunity for that island nation to revive its sluggish economy.

In March, I published my first book, Weeb Economy — but only in Japanese. Half of the book was a series of translated posts from my blog, so those are already in English. The other half was a new part that I wrote in English and had translated into Japanese by my excellent translator, Kataoka Hirohito. Eventually the whole book will come out in English, but right now I’m publishing the new half as a series of blog posts. Here are the first two:

Part I: “I Want the Japanese Future Back!”. Here I explained why Japan is now basically a developing country again, and why this requires bold, persistent experimentation with new economic approaches.

Part II: “FDI is the Missing Piece of Japan’s Puzzle”. In this post I cited some prominent examples of how foreign-owned factories, research centers, and startups are already giving Japan’s cutting-edge high-tech industries a boost. I explained why one specific type of foreign direct investment — greenfield platform investment — is so much more important than the other types, and why Japan largely ignored this type of investment until recently. I explained the many benefits of greenfield platform investment, and listed some ways that Japan’s current economic conditions make it especially favorable to this type of investment.

In this third installment, I explain one of Japan’s most important advantages in attracting greenfield investment: the fact that everyone loves Japan and lots of people want to live there. I present data showing just how popular Japan is right now, and I try to give some explanations as to why people around the world love the Land of the Rising Sun so much.

The world loves everything Japanese, but Japan doesn’t realize it

In 2015, my employers at Bloomberg Opinion sent me to Japan to learn about the state of the Japanese economy. They helped me arrange many interesting discussions. I talked to the Financial Services Agency about the new corporate governance code; to Goldman Sachs about women joining the workforce; to Foreign Ministry officials about trade treaties; to an economics professor about fiscal sustainability; and so on. But the interview that stuck in my mind for many years after was with a manager at Kodansha.

My goal for the meeting was to learn about Japan’s efforts to increase its cultural exports — something the Western press had been talking about for decades. So I was absolutely astonished when the Kodansha manager told me that his company had no strategy and no plans to increase their sales of manga and anime in overseas markets. Even more surprising was his explanation as to why. “Americans don’t want to see Asian faces,” he told me.

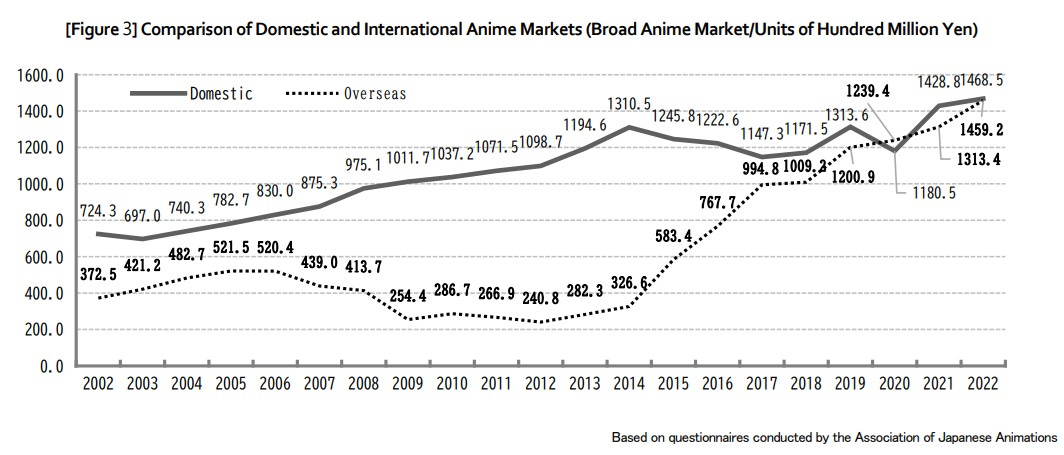

I stared at him in slack-jawed amazement. Nothing could be further from the truth, I told him. I didn’t have international statistics on hand, but I knew that Asian media was taking the U.S. by storm. Manga sections were steadily growing in American bookstores. K-pop was exploding in popularity. Cosplay conventions had become mainstream. Overseas anime sales were starting their long upward climb:

In 2015, these trends were already becoming apparent, but they’ve only accelerated. From the TV show Shogun sweeping the 2024 Emmy Awards, to the Korean film Parasite winning the Oscars in 2020, to Oscars for the Japanese movies Godzilla Minus One and The Boy and the Heron, to Korea’s BTS becoming the biggest band in the world, there has been no shortage of proof that “Asian faces” — or, more precisely, the products of Japanese and Korean imaginations — are exactly what the world wants to see.

But these examples can’t fully convey how Japanese pop culture, in particular, has become a memetic shorthand that young generations in America and many other countries use to communicate, to define themselves, and to understand the world.

When I moved to a new apartment last year, the movers stopped to talk to me about anime. When I went to hang out with some venture capitalists at their lavish San Francisco apartment, they asked me if I wanted to watch some anime. When I tutored children in math as a college student back in the 2000s, it was hard to get the kids to pay attention, because they were drawing anime characters in their notebooks. Anime tropes like “Notice me, senpai!” have crept into the American lexicon. When I go to my friends’ startup offices, there are manga volumes on the shelves. When I argue with strangers online, their avatars are faces from anime.

These aren’t just anecdotes. A survey of Americans by the website Polygon in early 2024 found that 42% of Gen Z watches anime every week, compared to just 25% who watch the NFL. Younger survey respondents reported that anime influences many basic aspects of their life — style, identity, friendship, and even attraction. (That’s just in the U.S., but as far as I know, this trend is worldwide — anime viewership is growing even faster in Europe, Brazil, and the Anglosphere.)

In fact, the increasing Japanese influence on American life goes far beyond pop culture. Over the past two decades, Japanese food has increasingly become the most sought-after cuisine. New Yorkers line up around the block to get into ramen restaurants that would be considered average in Japan. Wagyu has become a national obsession. Omakase has become a pinnacle of find dining, and words like kaiseki and izakaya are becoming part of the standard lexicon. Matcha has become a delicacy — expensive shops advertise “the finest matcha tea from the shade-grown farms of Kyoto, Japan”. Even non-Japanese restaurants sometimes affect Japanese names and pseudo-Japanese decor in order to seem higher class — allowing to charge a hefty price premium. It’s hard to find a high-end cafe or restaurant in San Francisco these days that doesn’t have something yuzu-flavored.

Nor is it just food. In the high-end home furnishing stores where rich Americans shop, Japanese-made ceramics and other objects command a hefty price premium. At the more affordable end, Daiso, Uniqlo, and Muji have become all the rage. Japanese artists like Kusama Yayoi have become such staples of high culture that the trend has been parodied in Netflix dramas. Fashionistas in trendy cafes will have B-side Label stickers on their laptops and bags.

As with food, even the veneer of Japanese fashion and design is enough to impart a sense of high class and good taste. Seeing boutiques with katakana on their signs on St. Mark’s Place in New York City, or Haight Street in San Francisco, is now commonplace, even if the goods inside aren’t from Japan. Trendy American brands will give themselves Japanese-inspired names like “Baggu”. I often joke that the U.S. is in the middle of a great shift — in the 19th and 20th centuries, high class in America was defined as “anything French”, while in the 21st century it’s defined as “anything Japanese”.

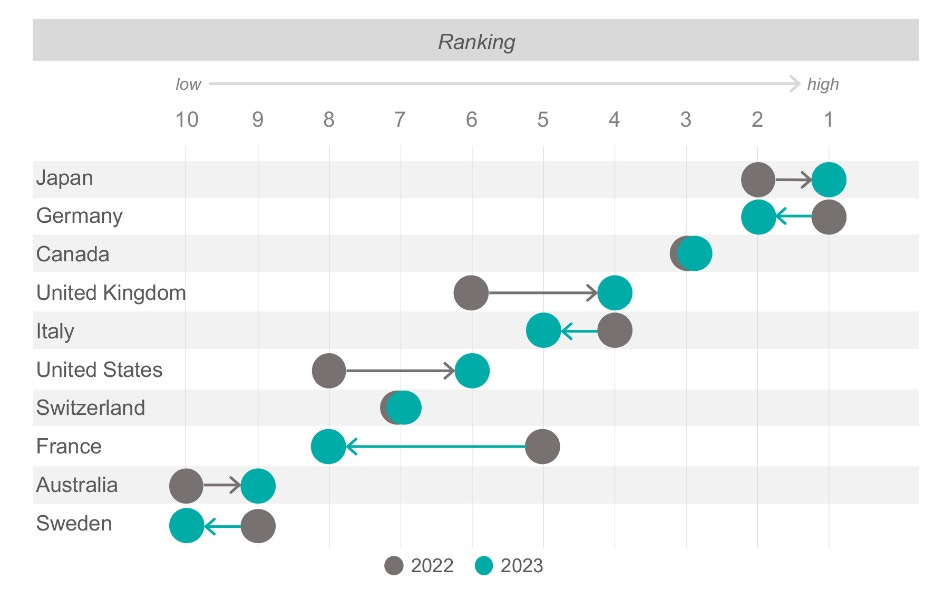

Japan’s international cachet can be seen in a variety of international surveys and rankings. In 2023, Japan topped the Anholt-Ipsos Nation Brands Index, which has measured international perceptions of various developed countries for 15 years:

Japan also regularly comes in at or near the top of a similar international survey by the BBC. Recently, Japan was ranked #2 on U.S. News and World Report’s list of the “best countries in the world”, which combines various subjective metrics to assess a country’s international appeal. And another survey by Conde Nast put Japan in the top spot.

In my experience, most Japanese people are generally unaware of any of this. Earth became a weeb planet in spite of the failure of the Japanese government’s attempts to promote Japanese culture overseas. It has been an organic, disorganized, bottom-up phenomenon — Japanese culture simply holds a special appeal to the people of the U.S. and much of the rest of the world.

The most important word about Japan that Japanese people don’t know

In fact, even more astonishing than my interview with Kodansha is the fact that to this day, I have not met a single Japanese person who has heard of the word “weeb”.

Explaining the meaning of the word “weeb” is actually a little tricky, since it comes from internet slang. It was originally a short form of “weeaboo” — a nonsense word invented on an old web forum, meaning a non-Japanese person who is obsessed with Japanese culture.

The dictionary definition of “weeb” still claims that it’s a derogatory term for people who are overly obsessed with Japan. But this hasn’t been the case for a while. Like the word “otaku” in Japanese or “nerd” in English, “weeb” started out as an insult but eventually became a semi-ironic badge of honor. And like those other slang words, “weeb” has come to be applied in a much looser, more casual sense.

There are still the classic, hardcore weebs — the people who flock to anime conventions and enter cosplay competitions and study Japanese just so they can play the untranslated versions of every Final Fantasy game. These enthusiasts form a vibrant and highly original subculture that has spread throughout the world. In another essay in this volume, I try to explain this subculture.

But like “otaku” and “nerd”, “weeb” is starting to take on a looser, more general meaning. Just as anyone these days might jokingly refer to themselves as an “hiking otaku” for enjoying hiking, or a “tea nerd” for knowing a lot about tea, people in the English-speaking world are starting to refer to themselves as “weebs” for liking Japan and Japanese products in general.

It is in that looser, more general sense that America — like an increasing number of other countries — has become a weeb nation. And it is in this more general sense that the worldwide weeb trend can help Japan reclaim its position as a global center of high-tech innovation.

Everyone wants to go to Japan, and they’re starting to realize they can

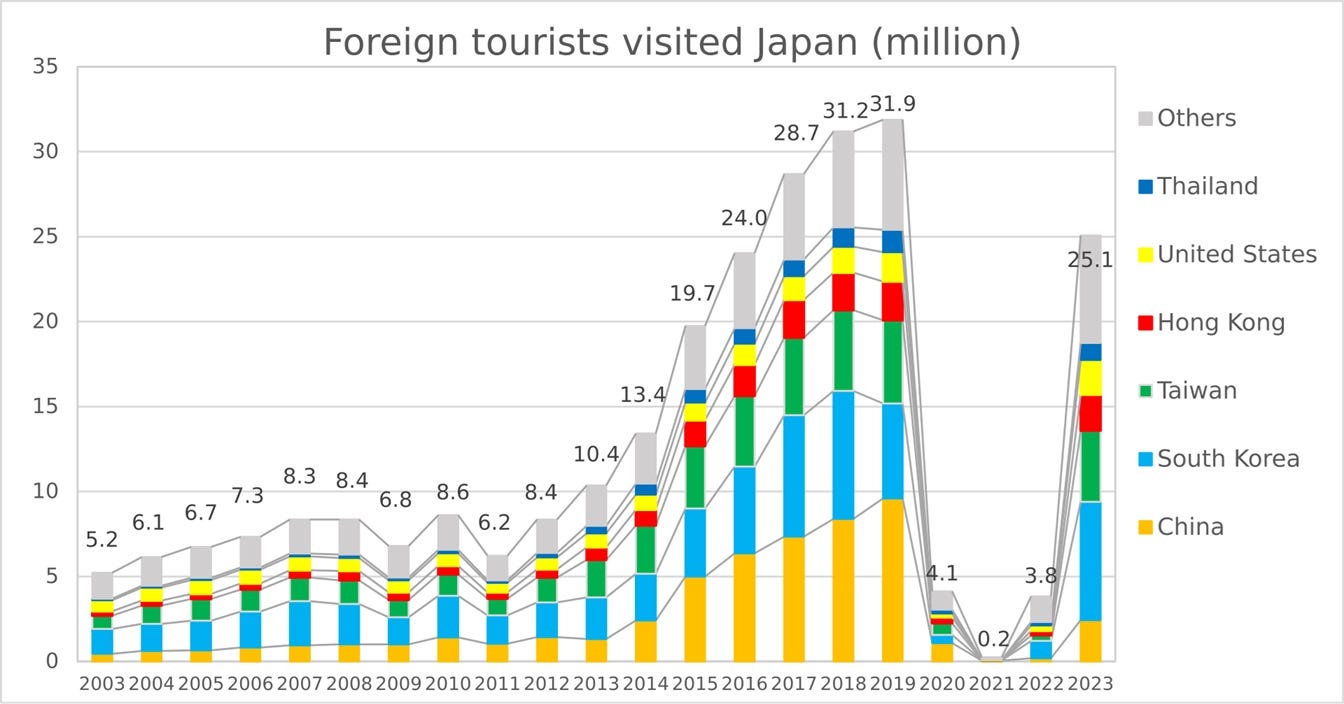

By now, everyone in Japan knows all about the tourism boom, but the numbers are still staggering. In 2007, 8.4 million tourists came to Japan. By 2019 that number had almost quadrupled, and is now rebounding sharply from the pandemic:

The Japanese government intentionally encouraged tourism starting in the early 2000s, but the boom since 2012 has far exceeded their targets. So many people are visiting Japan that it’s straining local infrastructure, causing overcrowding, and prompting the locals to ask when the flood will recede. So far there’s no sign that foreigners are getting bored with Japan; tourism numbers in 2024 look set to top the record set in 2019, with increasing arrivals from the U.S. and Europe more than canceling out a drop in visitors from China. Personally speaking, almost everyone I know in San Francisco is either going to Japan these days, or wants to go. Some have started going multiple times a year.

Eventually, something will probably have to be done about overtourism. But the boom in foreign travel to Japan has accomplished several important things, all of which will be potentially useful in boosting investment into Japan.

First, it has familiarized much of the world with Japan — what was once a mysterious far-off land is now just one more place you can go and hang out when you get some vacation time. And instead of reducing Japan’s overseas cultural cachet through boredom and familiarity, the tourism boom seems to have only deepened foreigners’ love of Japanese food, art, and culture.

Second, tourism is forcing Japanese cities — especially Tokyo — to become more user-friendly to foreigners. Signs in English and other foreign languages have proliferated, shopkeepers and restauranteurs are all used to dealing with non-Japanese customers, and so on.

Third tourism is rapidly dispelling the previously common stereotype of Japan as a closed-off, xenophobic country. Foreigners can now see for themselves how open, free, friendly, and welcoming of a country Japan actually is. For most people, this revelation makes little difference in their lives. But for a few, it has prompted a second realization — that instead of just visiting, they could go live and work in Japan.

Mass immigration to Japan remains dominated by people from poorer Asian countries, especially Vietnam and the Philippines. But a 2020 survey by the global money transfer service Remitly found that Japan topped the rankings of countries that Americans and Canadians would like to move to. Anecdotes about Americans moving to Japan are starting to proliferate. The real estate news website Mansion Global reports that “[Japan’s] appeal is now leading to a slow-growing influx of American expats moving to the country in search of full-time residences or second homes abroad.” Personally, I’m always surprised by the number of people I meet in the San Francisco tech industry who talk about moving to Japan. A few have even done it.

Two extremely important examples of Westerners who made this move are the founders of Sakana AI. On Lux Capital’s website, they note that Llion Jones “fell in love with Japan after spending a holiday there and moved to Tokyo in 2020.” As for Jones’ cofounder David Ha, he has spent much of his career in Japan since graduating from college.

It’s not just Westerners either. A growing number of Taiwanese people want to work in Japan. It’s not clear whether a desire to live in Japan on the part of TSMC’s workers was a factor in that company’s decision to invest in Kumamoto, but it certainly couldn’t have hurt.

Which brings me to the final effect of the tourism boom: It’s helping Japanese people to finally realize just how much the world loves their country. Japan may not yet know the word “weeb”, but it’s becoming conscious of the phenomenon itself.

But knowing that the world loves Japan is far easier than understanding why this is the case. In fact, there are no simple or easy answers to this question. I can venture my best guess as to the reasons for Japan’s unique global appeal, but it means I’ll have to venture beyond the realm of data and research and into the realm of supposition and amateur sociological theorizing.

It starts, I think, with Japan’s unique approach to urbanism.

Why people love Japanese cities

One strategy that Japan has tried in order to curb overtourism is to get tourists to visit small towns and rural areas instead of Tokyo and Kyoto. This strategy has failed, because Japan’s big cities are exactly what foreigners come to the country to see. To be sure, Japan’s rivers and mountains are beautiful, its small towns are quaint, and its temples and shrines are majestic. But what really makes Japan different from every other country in the world are its big cities.

Unless they have lived abroad, Japanese people have little idea what life in an American city is like. Unless you live in the center of New York City, life is typically lived in a point-to-point fashion. You move back and forth between your house, your office, and “third spaces” like stores, restaurants, bars, clubs, and parks. Usually you take a car, but perhaps sometimes a bicycle. If you’re poor you take a bus. The entire space between these points might as well be empty to you — you see signs and buildings as you drive by, but you’re usually focused on reaching your destination. A city thus becomes a network of points, rather than a space to be occupied.

This type of life can be comfortable, but it leaves little room for serendipity. Accidental meetings between friends and acquaintances are rare, unless there’s a cafe or bar that both people frequent. Accidental discovery of interesting new restaurants and shops are even rarer — instead, people use websites, word of mouth, and advertisements. And of course, accidental meetings with strangers are rare (which can be good or bad, depending on how extroverted you are).

Walkability and density are two reasons why Americans who move to Japan tend to feel like they’ve stepped into another universe. The ability to go anywhere without the stress of driving or the task of finding parking allows them a sort of freedom that few of them have ever known — Japanese people might consider an eight-minute walk to a train station to be unacceptably long, but to an American, that might as well be next door. And on the way to their destination, they’ll see far more people and far more interesting places to eat and shop. Where back home their commutes focused only on the destination, now the journey is half the fun.

Of course, Japanese cities are far from the only dense, walkable cities in the world. They also stand out for being extremely clean, quiet, and safe, and having some of the world’s most punctual and convenient trains. And Japanese urban infrastructure is always in excellent condition, due to timely and effective maintenance. But even these advantages aren’t quite unique — Zurich, Singapore, Stockholm, and Seoul all share those advantages. Japan’s cities have something extra special in addition.

I believe that that something is commercial density. Tokyo has an order of magnitude more restaurants than New York or Paris, and the disparity in retail stores is probably similar. Small business is the lifeblood of Japanese cities — and, in many ways, of the Japanese middle class. This might be partly cultural, but at least some of it is the result of deliberate policy. Japanese zoning usually limits the size of stores in mixed-use areas, ensuring that small businesses dominate. The Large-Scale Retail Store Location Law also provides some protection. And Japan’s government provides lots of support for people who want to start small businesses, including a variety of subsidies. This support, along with a culture of craftsmanship, might be why Japan’s independent restaurants and stores tend to stand out in terms of both quality and originality.

Commercial density is especially astronomical in central downtown neighborhoods like Shibuya, Shinjuku, and Ginza. Here Japan takes advantage of another secret weapon: verticality. In most cities — New York City, London, Paris, and even other Asian megacities like Hong Kong — most shops and restaurants are at ground level, with apartments and offices on the higher floors. But Japan has a special innovation: zakkyo buildings, with restaurants and stores mixed in with offices for several floors. These buildings have two special features: 1) signs all the way up the side of the building, and 2) direct street access via elevators and stairs.

Zakkyo buildings do two special things for Japanese cities. They allow a huge amount of retail to be concentrated in a very small space, in hyper-dense eating and shopping districts like Shinjuku. And they allow people walking past the buildings to see and access those shops and restaurants very easily from the street. This makes walking through a Japanese downtown an even more magical, serendipitous experience than walking through a city like New York — there are just so many more places to explore. And it also allows more residential areas very close to the city center to be surprisingly quiet and livable, since so much foot traffic is drawn to the ultra-dense downtowns.

Of course, Zakkyo buildings also give Japanese cities their characteristic aesthetic. Columns of colorful electric signs running up the sides of buildings might seem tacky or antiquated to some Japanese people, but to foreigners, they create a distinctive beauty — a forest of lights that feels at once both enticing and soothing. Japan’s electric cityscapes feel more like luminescent trees or clouds than like something artificial — utterly different from the garish lights of Las Vegas or the overwhelming harshness of Times Square. This may be one of those features of Japan that it takes a foreign perspective to appreciate.

Essentially, Japanese cities represent adventure — every day you walk out of your door in Tokyo or Fukuoka or Nagoya, you know you’re likely to discover an amazing new place to eat, a cool new boutique, or a fun new bar. And in those beautiful settings, you’re likely to meet interesting new people — new friends, business partners, or even lovers. Yet that adventure is a safe and comfortable one — urban Japan offers few dangers, or even inconveniences.

There are not many cities in the world that offer that winning combination. Traditionally, this is the role that Paris has played in the global imagination. But as I explain in another essay in this volume, Tokyo — and other Japanese cities — may be taking its place.

But although Japan’s unique urbanism is a big part of why foreigners are drawn to the country, it can only be part of the explanation — especially because many of the people who love Japanese products, and Japanese pop culture, have never even visited the country. There must also be cultural factors at work.

Japan as alternative modernity

For me to try to articulate which specific features of Japanese culture make it so uniquely appealing to foreigners is probably a lost cause. For one thing, culture is too complex to describe in language — the descriptions almost always end up being both boring and ambiguous, and usually fall back on tired stereotypes. It’s also likely that different aspects of a nation’s culture appeal to different groups of people. And since neither government, business, or private citizens has deliberate control over a nation’s culture, the exercise would be useless.

Instead, I think it’s more useful to realize what Japanese culture represents to foreigners, in a more general sense. And what I think it represents is alternative modernity.

Politically and economically speaking, Japan is part of the West. It’s a democratic, capitalist, developed country, with a notion of human rights similar to what prevails in the U.S. or Europe. It trades extensively with the U.S. and the EU, and it has strong scientific and intellectual links with both. It is neither a repressive one-party state like China or Russia, nor a theocracy like Iran, nor an aristocracy like UAE.

And yet in a million small ways, Japan is culturally distinct from the U.S. or Europe — or from anywhere else. It has different mannerisms, different social customs, and different aesthetic sensibilities. People relate to their coworkers and their friends and their families in different ways. Japanese institutions — companies, schools, bureaucracies — all do things a bit differently than their peers elsewhere. Even tiny aspects of Japanese culture, like preferences for brand goods, or the way people read the manual when they buy a new camera, feel different in ways that are difficult to describe but easy to recognize.

This high density of tiny differences manifests in almost everything Japan produces. To a Japanese person, the word “anime” refers to any cartoon, but to the rest of the world, it represents a specifically Japanese style that’s instantly recognizable and completely unique. Japan’s global in art, design, architecture, and fashion stem partly from a culture of craftsmanship, but partly from the fact that Japanese people simply tend to create slightly different kinds of designs.

In other words, Japan is a place that is substantively similar to other rich, democratic, and free countries, but feels different. To people all over the world, it represents an alternative to the standard global version of modernity descended from West Europe. People who value the wealth and freedom of European-derived societies, but who feel oppressed or bored by European-derived cultures, find refuge and novelty in Japan and its products.

There is thus no single reason that the world has gone weeb. Instead, there are a myriad of small reasons. For those who want to boost FDI into Japan, I would say that understanding and cataloguing all of these reasons is much harder than simply taking advantage of their existence.

I have started to believe it is about more than traditional or pop culture, more than the exchange rate, more than the charm of city and countryside. It's because Japan offers a different and more comforting take on what a modern society can be. You touch on this at the end, but let me go into a little more detail.

Consider that Japan missed many major consumer-facing tech trends of the 21st century -- it failed to lead in the social media, freemium gaming, alogrithmic curation, or AI spaces. In many ways, it feels like a place time stopped. Yet it doesn't feel backwards. Quite the contrary: it feels in many ways a sane, calm alternative to the West, and America in particular, where "disruption" might as well be on the dollar bill at this point. I write about this at more length here: https://blog.pureinventionbook.com/p/super-galapagos

Great article. One more thing for me personally -- Japan is also extremely affordable, especially for the quality of goods or services received. This is of course major function of the depreciation of the Japanese yen, but it still has the effect of making Japan accessible to a huge swathe of the global population in a way that New York, London etc is not (especially in terms of the quality of amenities received -- just compare a $300/night hotel in New York with a hotel half the price in Tokyo)