I have written a book!

It's called "Weeb Economy". But so far it's only in Japanese.

Here’s a bit of news: I’ve written my first book! Well, half a book, really. Half of it is a series of republished blog posts that I’ve written about the Japanese economy over the years, while the other half is a new section I wrote. It’s coming out in Japan on March 19th; if you want a copy, you can order one here. The title is Weeb Economy: ウイーブが日本を救う, which translates to “Weeb Economy: The Weebs Will Save Japan”.1 It was translated from English by the excellent Kataoka Hirohito, who has been translating my blog posts for over a decade.

I have to admit, publishing a book on the Japanese economy with the word “weeb” in the title is pretty on brand for me.

Yes, it’s a funny title. But surprisingly, almost nobody in Japan knows the word “weeb”,2 so I’m hoping that the novelty will be eye-catching, and that teaching the country a fun and important new word will provide a good excuse to expound my own ideas about how to revive Japan’s stagnant economy.

The new half of the book is all about how Japan can leverage its global cultural appeal to get more foreign direct investment. As things stand, most FDI into Japan comes in the form of mergers and acquisitions — foreign companies buying Japanese companies in the hope of using them as beachheads to sell into the Japanese market. Japanese people are understandably wary of this type of investment, since it doesn’t really create jobs, and the acquired companies are often mismanaged.

But what Japan really needs is more greenfield platform FDI — companies building factories or research facilities in Japan in order to make and sell products to the rest of the world, or foreign entrepreneurs starting export-oriented startups in Japan. That kind of investment has been used to supercharge the economy of Poland, which is due to overtake Japan in terms of living standards in the near future. As a country, Japan’s exports are surprisingly weak, it has fallen out of many key global supply chains, and its technological ecosystem is often isolated from the rest of the world. Greenfield platform FDI can help fix that, by reintegrating Japan with the global economy, bringing in foreign technology, and pumping up exports.

The basic thesis of Weeb Economy is that the world would love to invest more in Japan, because technologists, entrepreneurs, and businesspeople all over the world would love to live in Japan. Over the last decade or so, there has been a general realization that Japan is a great place for tourism; the country is friendly to foreigners and is easy to navigate. But what most people still don’t realize is how easy it is for foreigners to live and work in Japan.

Once they realize that key fact, I believe that lots of people will choose to move and invest. Already, there are some encouraging examples — TSMC fabs in Kumamoto, AI startups in Tokyo, and so on. This is no coincidence. Japan’s culture — not its traditional culture, but its modern way of life — carries a unique appeal that has captivated the hearts of untold millions around the world, including a disproportionate number of people working in high-tech industries. And Japan’s cities are some of the best places to live on Earth.

So I think there’s a huge opportunity here for Japan to add a whole new piece to its economic machine, which can bolster and enhance all the other pieces. In the book, I offer some ideas on how the Japanese government and businesses can speed up the development of the “weeb economy”.

OK, now for the bad news: The book is only available in Japanese right now, so odds are you probably can’t read it yet (unless you feel like using an AI translation app and a smartphone camera). It’ll eventually come out in English at some point, but I don’t know exactly when.

But now for more good news: Since half of the book consists of translated blog posts that I’ve already published on this blog, you can just go read the originals! Here are some posts that got included in the book:

And here is a short excerpt from my initial English-language draft. Enjoy!

Part I: I want the Japanese future back!

Japan lost the future in 2008, not in 1990

When I lived in Japan in the mid-2000s, it still felt very much like “the future”. 3g flip-phones with grainy cameras were far more advanced than anything I had encountered in the U.S. Japanese people had LCD or plasma TVs, while most Americans were still using old cathode-ray machines. Their kitchens had automatic rice-cookers and other appliances I had never seen, and their laptops were higher-performance and far more durable than the ones I had used in the U.S. Their toilets were like something from a spaceship, and their showers could dry clothing. Some people even had digital SLR cameras that could shoot movie-quality video — a miraculous technology I had never even dreamed was possible.

And the cities! Giant screens adorned the sides of buildings, like something out of science fiction. There was always a train station within walking distance that would take me anywhere I wanted to go. The trains were clean and fast and they ran on time, and they even had electronic screens that told you when the train would arrive at the next station. Japanese cars and even motorcycles glided along quietly, where in America they roared and grumbled. Even in the U.S., of course, the most revolutionary, futuristic car — the Toyota Prius — was a Japanese model.

In the 21st century’s opening decade, Japan felt like it had embraced that new century while America was still lingering in the 20th. William Gibson, the celebrated creator of the cyberpunk science fiction genre, wrote this in 2001:

The world's second-richest economy, after nearly a decade of stagflation…still looks like the world's richest place, but energies have shifted…yet it feels to me as though all that crazy momentum has finally arrived…[T]onight, watching the Japanese do what they do here, amid all this electric kitsch, all this randomly overlapped media, this chaotically stable neon storm of marketing hoopla, I've got my answer: Japan is still the future, and if the vertigo is gone, it really only means that they've made it out the far end of that tunnel of prematurely accelerated change. Here, in the first city to have this firmly and this comfortably arrived in this new century - the most truly contemporary city on earth - the center is holding…Home at last, in the 21st century.

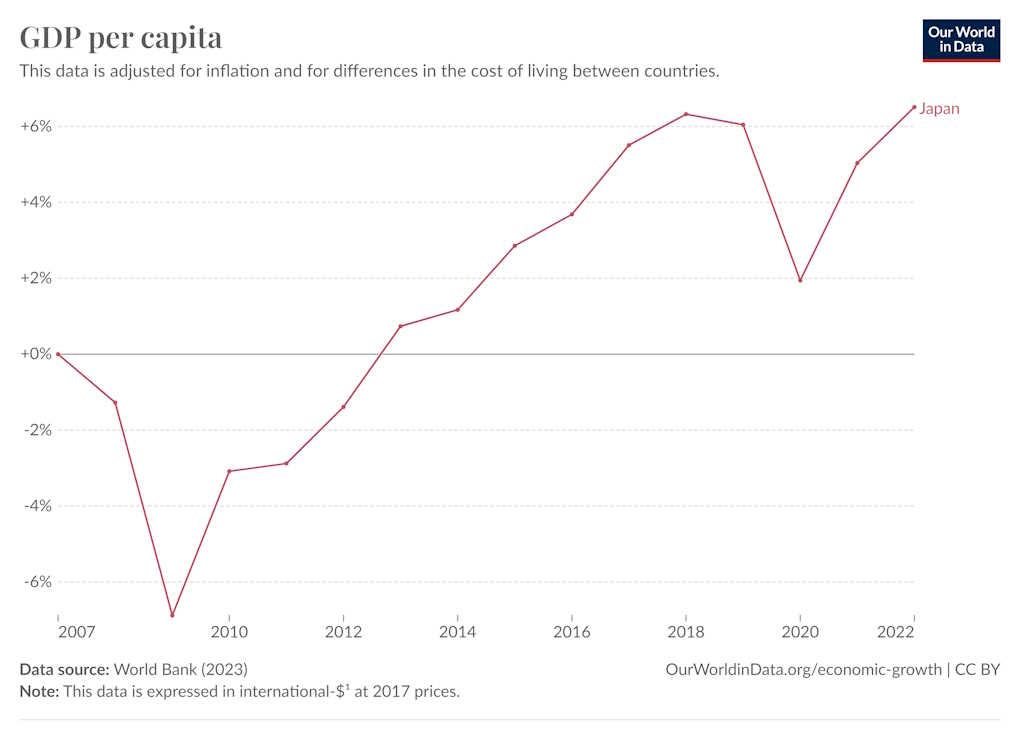

Now realize that the Japan of my earliest memories — the early and mid-2000s — was a full decade and a half after the famous bursting of Japan’s economic bubble. I am not hearkening back to the go-go days of the 1980s. By the time Koizumi Junichiro was in office, Japan’s “lost decade” had come and passed, full employment had been restored, and the country had returned to slow but steady economic growth. Despite the overhang of the bubble era, Japanese per capita incomes, measured at international price levels, grew by a respectable 20% between 1990 and 2007:

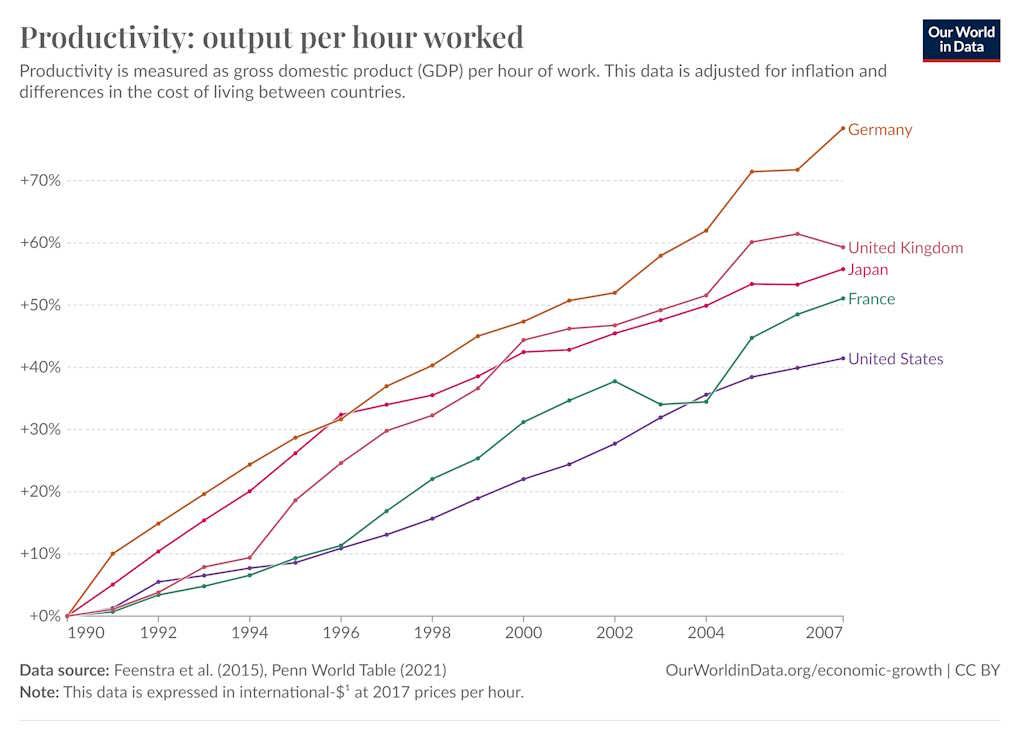

This was slower than the U.S. or West Europe, but that was mainly due to Japan’s more rapid population aging, which was increasing the percentage of retirees. In terms of GDP per worker, Japan kept pace with other rich countries over this time period, and even outgrew the United States:

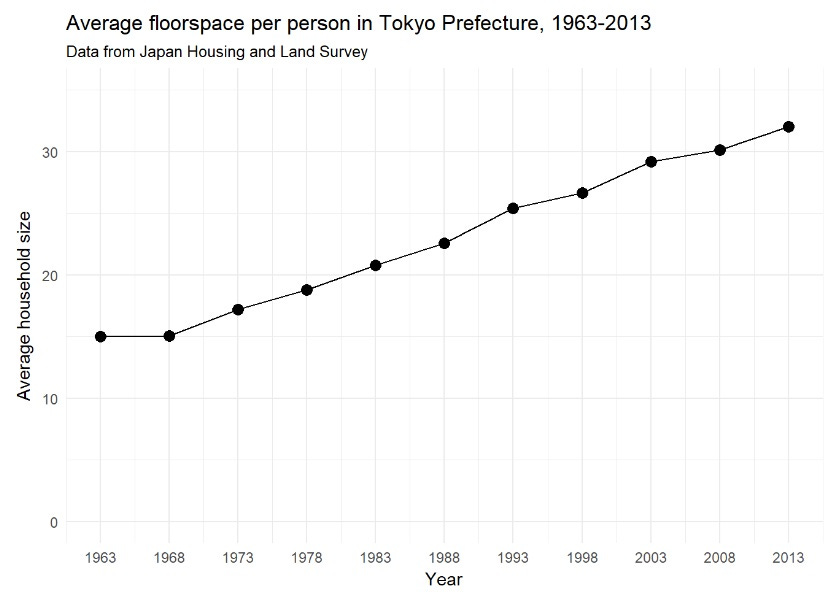

And this growth was being felt by regular Japanese people. It wasn’t just fancy gadgetry and big screens. Japanese houses were getting steadily bigger, growing from the tiny “rabbit hutches” of the postwar period into something similar to what Europeans enjoyed:

Japanese people were eating better, too, as local chefs and entrepreneurs took advantage of imported food to create the world’s best restaurant scene, and big new grocery stores like Aeon revolutionized home cooking. Gyms, cafes, and all kinds of public spaces were improving in quality and quantity. Culturally, Japan still felt at the cutting edge, with a vibrant street fashion scene, a golden age of anime and manga, a burst of musical creativity, and an explosion of online culture driven by websites like Niconico.

Given all this, it’s reasonable to ask whether Japan’s so-called “lost decades” after the bubble era were really lost at all. Japan’s catch-up growth had ended, and its living standards were still a bit below the very richest countries like Switzerland or Singapore, but it was solidly within the first rank of nations, and it was still upwardly mobile. It was innovative and vital, at the cutting edge of both technology and culture. And it had accomplished all of this without the kind of deep wrenching disruptions that America experienced after its own real estate bust.

But in the years since 2007, it feels like that Japanese future has been lost. Living standards grew only 6.5% between 2007 and 2022.:

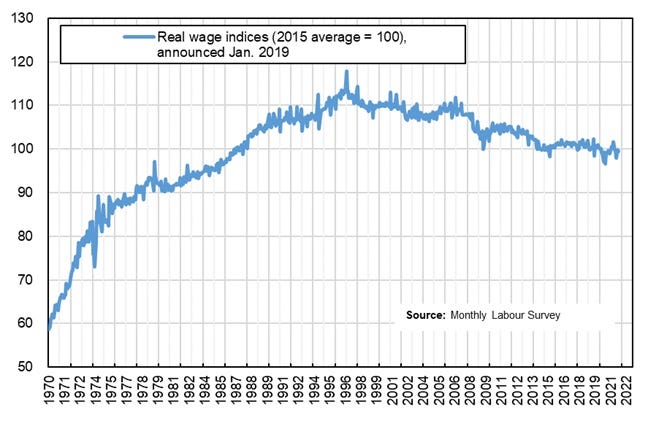

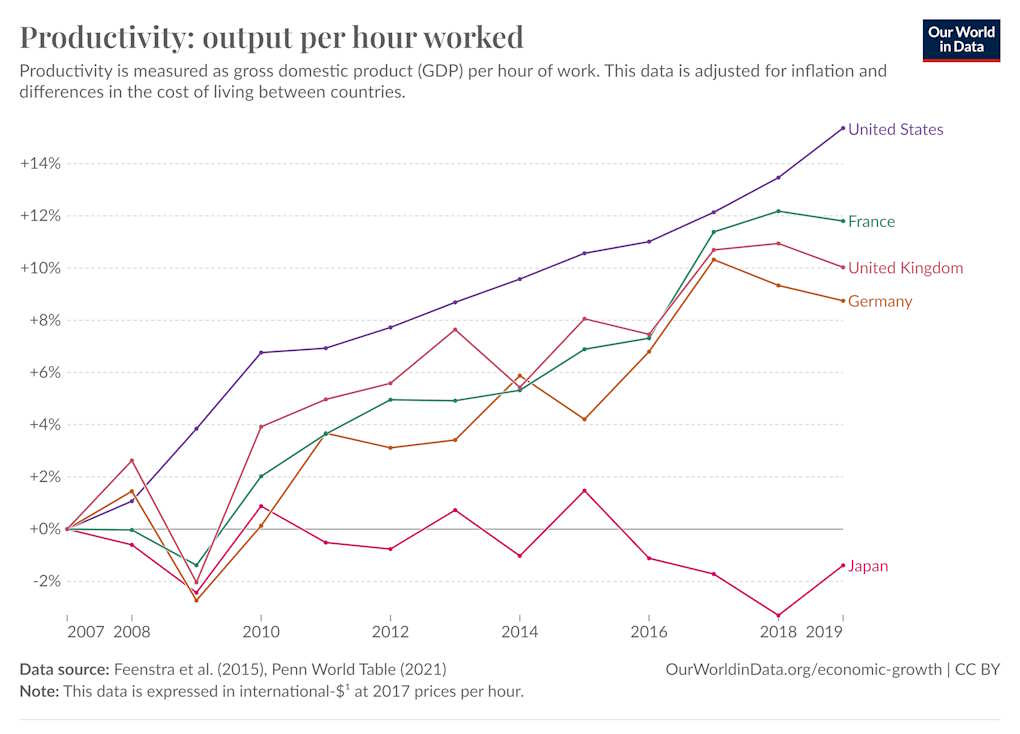

And even that meager amount of growth was entirely due to increased labor input — women, old people, and young people going to work — rather than to productivity increases. In fact, Japanese workers produced less per hour in 2019 than in 2007, falling well behind other advanced nations:

Why did Japan stagnate starting in 2008? It’s not clear. Potential culprits include the global financial crisis, the big earthquake and nuclear accident of 2011, the subsequent shutdown of nuclear power, rapid aging, the retirement of the Baby Boom generation, and the ramping up of Chinese competition. Perhaps it was all of these combined. But whatever the reason, 2008 was the turning point.

This doesn’t mean Japan has stagnated in every regard. Its big cities continue to build themselves up, and its restaurants and shops have continued to improve. But when I go back to Japan each year, I can clearly feel the loss of that futuristic vitality that I felt 17 years ago. Japan’s consumer electronics are no longer the cutting edge, having long ago been supplanted by Apple and various other brands. Its auto companies have been caught flat-footed by the switch to battery EVs, and are now — like most Western brands — are in danger of losing the global market to innovative Chinese competitors.

America’s household appliances have caught up and surpassed Japan’s — plenty of American homes now sport Instant Pots, air fryers, sous vide cookers, video doorbells, smart speakers, and so on. Japan still has much better toilets, and there have been some locally specific innovations such as better air purifiers. But for the most part, Japanese homes still feel like they’re stuck in 2007. And that’s not even considering furniture, which tends to be much higher-quality in the U.S.

This does not mean Japan is a bad place to live, or that it’s no longer a rich country. Far from it. In fact, the amenities of life — the safety and friendliness, the visual beauty, the infrastructure, the unparalleled retail experience, and so on — make it extremely pleasant in ways that richer countries often fail to match. And if, like me, you’re a foreigner with an American salary who works remotely and sets his own hours, Japan can feel like a paradise. (In fact, this will be important for my argument in a bit.)

But for average Japanese people, life in Japan is hard to afford. Average real wages have actually decreased since 1996:

The situation is actually not quite that bad, since it involves substantial composition effects — falling labor hours, the retirement of highly paid Baby Boomers, the entry of more part-time workers into the labor force, and so on. In fact, hourly wages have increased by a modest amount. And the rise of women’s employment since 2002 has taken some financial pressure off of many families by adding a second income, just as it did in the U.S. in the 1980s and 1990s.

But the shift to dual-income households can only happen once. Ultimately, stagnant productivity and low overall growth will continue to make life a slog for the average Japanese family. The weak yen, which is caused in part by Japan’s slow growth, will continue to make imports expensive. And as the percentage of the elderly continues to steadily increase, Japan’s working-age citizens will have to toil more and more simply to afford the same standards of living — unless productivity can be raised.

Because being “the future” isn’t just about having fancy gadgets and cool screens on buildings. Technological progress — the development of new products and better production processes — is the ultimate font of a nation’s quality of life. If Japan can reclaim the mantle of “the future” — if it can reach the technological cutting edge across a wider array of products — it can secure an easier, more fulfilling life for its people.

Ultimately that is why I want the Japanese future back.

The official title is actually just ウィーブが日本を救う: 日本大好きエコノミストの経済論, which translates to “The Weebs Will Save Japan: Economic Theory From a Japan-Loving Economist”. But “Weeb Economy: The Weebs Will Save Japan” is what’s actually on the cover. Japanese publishing is…a bit different.

In the general sense, a weeb is a non-Japanese person who likes Japanese culture. Usually, it’s used to refer specifically to people who are obsessed with Japanese animation and comics, but in my book I use it to just mean anyone who thinks Japan is an especially cool place. By that standard, most of us are weebs.

Congratulations on publishing the book! Pre-ordered. 日経BP is a fantastic publisher. I co-translated Hans Rosling’s “Factfulness” into Japanese (2019) and it was also published by 日経BP. It printed over 1 million copies in Japan in 2 years. Email me at [redacted] if you want to brainstorm promotion strategies. I’d also like to write a book review once it’s out!

"But the shift to dual-income households can only happen once"

tell that to my polycule