FDI is the Missing Piece of Japan’s Puzzle

Part II of my book, Weeb Economy.

My book, Weeb Economy came out in March, but only in Japanese. Half of the book was a series of translated posts from my blog, so those are already in English. The other half was a new part that I wrote in English and had translated into Japanese by my excellent translator, Kataoka Hirohito. So while I’ll eventually republish the whole book in English, what I can do right now is to publish my English-language first draft as a series of posts on this blog.

The first installment was entitled “I Want the Japanese Future Back!”. In that post, I explained why Japan now finds itself in the position of a developing country, playing catch-up with other countries. This means Japan needs to experiment with bold new strategies and development models, as it did in ages past.

In this second installment, I suggest one such experiment: a huge increase in a kind of investment called greenfield FDI. I discuss:

How Japan is already benefitting from greenfield FDI in a few places

Why greenfield FDI (a foreign company building a factory or research center in Japan) is so much more important and useful than other kinds of FDI like mergers and acquisitions

Why Japan needs to export a lot more to other countries, and how greenfield FDI can help do that

How Japan can start to welcome more greenfield FDI

Why Japan is an attractive destination for international investment

The Kumamoto miracle points the way

The semiconductor industry is probably the most important industry in the world. Computer chips are absolutely essential to every high-value product in a modern economy — autos, rockets, appliances, machinery, everything. They’re also of crucial military importance, in an age where precision weaponry rules the battlefield. And they’re of core importance to emerging technologies like AI — whose vast computational resources require enormous data centers — and biotech.

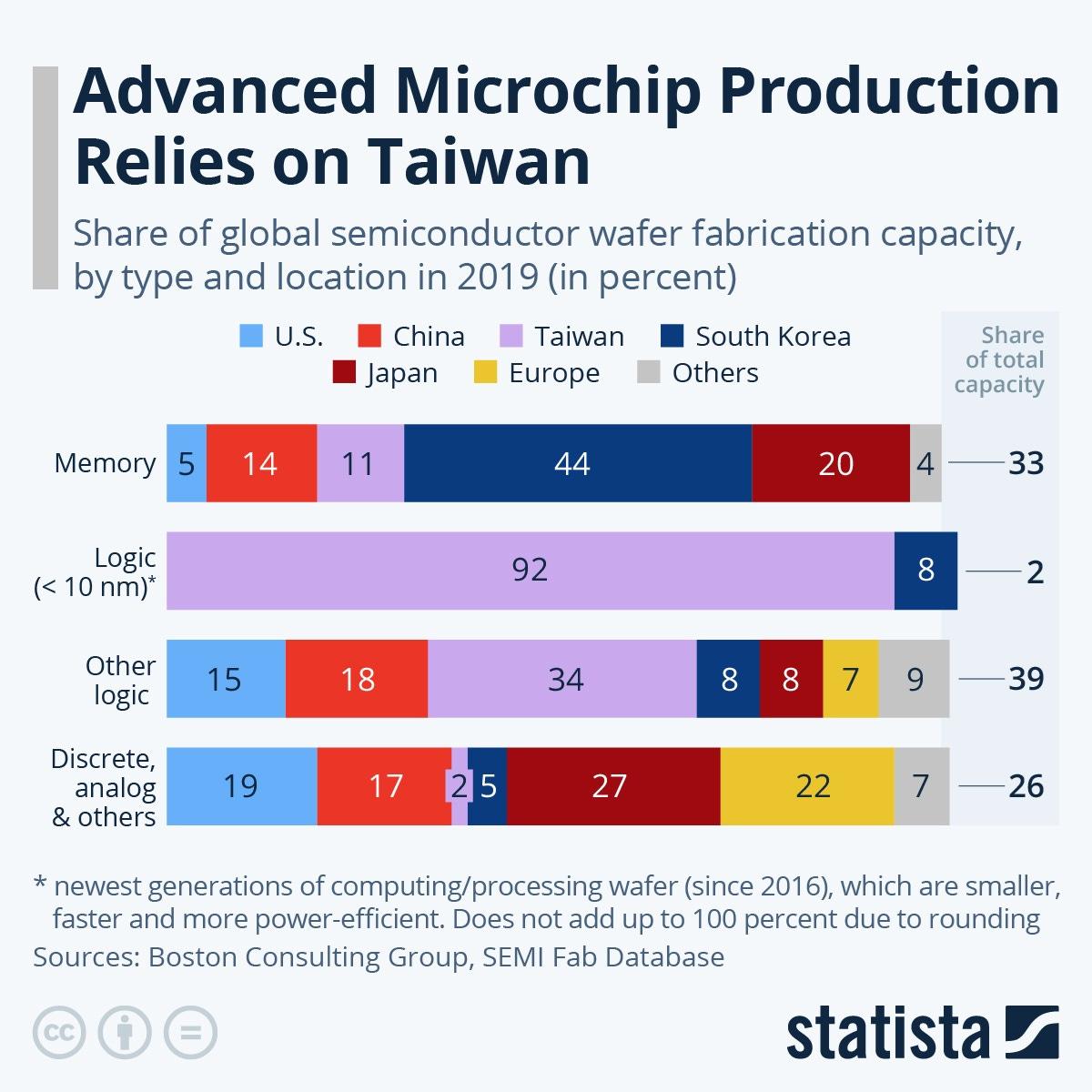

As a result, it’s no wonder that the world’s major economies have been fighting over the semiconductor industry for generations. In the early days, the U.S. and Japan were the clear leaders. Much of the industry involves the design of semiconductors and the production of specialized tools and materials, and in these upstream parts of the industry the U.S. and Japan are still strong. But in the most important downstream part of the process — the actual fabrication of the most advanced chips — both the U.S. and Japan have lost their lead to Taiwan:

Specifically, they have lost their lead to one remarkable Taiwanese company: Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company. TSMC are essentially the world’s greatest machinists. Other companies design the chips, and other companies create the (incredibly advanced) machine tools that make the chips. What TSMC does is to buy the tools, and then use the tools with incredible ingenuity and efficiency to make someone else’s chips designs into reality. They pioneered this “pure-play foundry” business model, and it has made them rich — and it has allowed Taiwan to outcompete the chipmaking industries of every other country on the planet.

Since the pandemic, the global battle to win semiconductor market share has intensified, due to the advent of AI and to the geopolitical competition between China and the democratic countries. Japan, like many countries, is trying to build its own foundry business, in the form of Rapidus, a joint venture between a bunch of Japanese companies that’s also getting some help from IBM. But — also like in the U.S. there’s also a second, parallel effort afoot. Japan is building chips for TSMC.

In late 2021, TSMC created a Japanese subsidiary called Japan Advanced Semiconductor Manufacturing (JASM), and started building two fabs in Kumamoto prefecture. Sony and Denso pitched in to help. So did the Japanese government, providing billions of dollars in subsidies and offering TSMC logistical assistance in finding local workers and ensuring adequate water and other infrastructure. The first plant was completed very quickly, and opened in February 2024; the second is expected to open in 2025. Now TSMC is considering a third fab in Kumamoto, producing even more advanced chips, to be opened in 2030.

Observers have been impressed with the speed with which the fab was built, comparing it favorably to TSMC’s plant in America, which initially suffered delays. TSMC credited the successful construction to a variety of local supporting institutions — “suppliers, customers, business partners, government and academia.” TSMC’s founder Morris Chang, who once poked fun at Japan for the slow speed of its business dealings, has now become a true believer in the revival of the country’s chip industry. At the opening of the first TSMC plant in Kumamoto, Chang predicted a “renaissance of semiconductors” in Japan.

And Japan isn’t stopping with TSMC. Micron, an American chip company, is building a fab in Hiroshima, bringing some of its best technology into the country. Samsung is building a semiconductor development center in Yokohama. Both of these investments are being done with significant help from the Japanese government, and involve cooperation with Japanese companies and universities.

These investments by foreign companies aren’t Japan’s only strategy for reviving its semiconductor industry — they coexist alongside homegrown efforts like Rapidus, as well as Japan’s upstream efforts in the chipmaking tool and materials industries. But they represent a crucial addition to the purely indigenous efforts. This is an example of multi-strategy development at work.

But it’s far from the only such example.

A school of AI fish

The artificial intelligence boom is the most important trend in the software industry right now. Whether this remains true in future years remains to be seen, of course, but the capabilities of large language models like ChatGPT, AI art software like Midjourney, and computer vision systems are undeniable. Even if there’s a bubble and bust in the field at some point — as there was with dot-com companies in 2000 — AI is going to be important in the long term.

Japan largely missed out on the internet software boom — the country has no internationally dominant consumer internet giants like Google or Facebook, and its B2B software industry was hampered by Japanese companies’ slowness to adopt IT solutions in past decades. But the AI age is a new dawn, and Japan has another shot at building a powerful software industry.

At the time of this writing, one of the most interesting AI startups in Japan is Sakana AI. Currently, AI applications generally use one large statistical model to generate text, create images, recognize objects, predict the shape of a protein, etc. Sakana tries to instead use groups of smaller models to accomplish the same thing. In addition to being able to do some things better than big models, these groups of smaller models may use much less electric power — an important consideration, when AI’s energy needs are skyrocketing.

Sakana AI has three founders. There’s Llion Jones, originally from Wales, who was one of the authors of the groundbreaking 2017 research paper that discovered the algorithm now used to make LLMs. There’s David Ha, originally from Canada, who was an AI researcher at Google Brain. And there’s Ito Ren, a Japanese former diplomat who was an executive at the e-commerce company Mercari.

The company’s investors are equally international — it includes American venture capital firms like Khosla Ventures, Lux Capital, and New Enterprise Associates, the American semiconductor giant Nvidia, and a large assortment of Japanese banks and technology companies. Sakana’s most recent funding round raised $214 million, and valued the company at $1.5 billion.

That’s not a huge valuation compared to U.S. giants like OpenAI ($150 billion) or Anthropic (possible valuation of $40 billion). But Sakana’s presence has put Japan on the map as a potential hotspot for international AI investment. Nvidia, for example, has declared its intention to create an R&D center in Japan. OpenAI has opened a branch office in Tokyo. Oracle is investing $8 billion over the next decade in AI and cloud computing in Japan. This is in addition, of course, to all the big cloud providers — Amazon, Microsoft, and Google — looking to invest in Japan in order to serve the Japanese market.

Then there’s Spellbrush, a U.S. startup that has a partnership with the AI art and design company Midjourney. Spellbrush uses generative AI to create Japanese-style anime art — one of the most popular and lucrative applications for AI so far. Spellbrush recently opened a branch office in Tokyo’s Akihabara neighborhood.

Japan is still behind the U.S. and China in AI, but investments like these keep it in the game.

It’s important to note that although Sakana AI might succeed, the most likely outcome is that the company will fail. This is true because most startups fail in general, and because in a rapidly changing new industry like AI, the failure rate is likely to be even higher. In fact, the entire AI industry may be headed for a significant bust, like the dotcom crash in 2000.

But this shouldn’t negate the importance of Sakana, or of the Japanese AI boom in general. First of all, though most startups fail, the few that succeed often grow very large and important — venture investing is about accepting many failures in order to find a few huge wins. The investment and attention that Sakana draws to the Japanese AI startup scene will help make sure that some of those successes happen in Japan. Even a general AI bust will likely only be a temporary setback to the industry, as with the dotcom crash and the subsequent recovery.

Second, even failed startups often contribute crucial innovation to a country’s ecosystem. Fairchild Semiconductor wasn’t successful, but it pushed the envelope of semiconductor technology forward, and some of its alumni went on to found Intel. General Magic tried and failed to invent the smartphone in the 1990s, but its alumni went on to help create the iPhone.

And third, Sakana sends a signal that Japan is a viable destination for international investment in the software industry in general, well beyond AI. Japan is generally weak in most areas of IT, including B2B solutions, consumer internet companies, and cloud computing providers. As in semiconductors, a wave of foreign entrepreneurs and foreign funding could help Japan shore up its weak spot in software.

The most important kind of FDI

The chipmaking projects by TSMC, Micron, and Samsung, the U.S. VCs’ investment in Sakana AI, and the branch offices of companies like OpenAI are all examples of foreign direct investment, or FDI. But they’re not the only type, and when people talk about FDI, they often mean something very different. In fact, it’s actually a bit of a confusing term, because it encompasses multiple unrelated categories of investment. FDI includes:

Cross-border real estate purchases

Acquiring a foreign company (M&A)

Building a branch office or factory in a foreign country (“greenfield” investment)

Most writers who advocate for Japan to increase FDI focus on the second of these. They believe that allowing more foreign acquisition of Japanese companies will improve these companies’ productivity by transferring foreign management techniques.

I am agnostic concerning this argument. I recognize that Japan’s policymakers and businesses have many reasons for resisting foreign acquisitions, both as part of the country’s development strategy and part of its social policy. Foreign buyers might downsize Japanese companies by firing large numbers of employees, which would hurt Japan’s corporation-centric social welfare model. They might strip-mine Japanese companies for their technology or other assets and then sell them off as husks of their former selves, as happens all too often with leveraged buyouts in the United States. Or they might simply neglect their Japanese acquisitions until they stagnated.

Instead, my argument is that Japan should focus specifically on increasing and promoting greenfield FDI — foreign companies building their own branch offices and factories in Japan. And in particular, Japan should encourage greenfield platform FDI, in which a foreign company builds factories or offices in Japan in order to create goods and services that are then exported from Japan to a third country. TSMC’s chip fabs in Kumamoto are an example of greenfield platform FDI.

This particular kind of FDI offers a lot of benefits that foreign takeovers don’t. For one thing, greenfield FDI usually directly adds to the economy — when a foreign company builds a factory in Japan, or even just purchases office equipment for a new office, that represents real money that goes directly into Japanese people’s pockets. And greenfield FDI inevitably results in the hiring of more Japanese workers, since someone has to work at the new factory or office branch.

Investment spending and workers’ salaries in turn stimulate the surrounding local economy — already, Kumamoto is experiencing an economic boom. Note that M&A doesn’t necessarily accomplish any of this — it just changes ownership of existing businesses, without requiring any new investment, hiring, or spending on the local economy.

And greenfield FDI is also more likely to be received warmly by the Japanese public. Ito, Tanaka, and Jinji (2023) find that Japanese people feel more positively about greenfield FDI than about foreign acquisitions:

This study empirically examines the determinants of individuals’ attitudes about inward foreign direct investment (FDI) using responses from questionnaire surveys that were originally designed. Individuals’ preferences for inward FDI differ between greenfield investments and mergers and acquisitions (M&A), and people are more likely to have a negative attitude toward M&A than greenfield investments. People with a negative image of the so-called “vulture fund” for foreign capital tend to oppose inward FDI, and this is more pronounced for M&A than greenfield investments.

On top of all this, greenfield platform FDI has a very good economic track record. It has been key to the economic success of a number of developing countries — most notably China, but also Poland and Malaysia.

After China’s entry into the World Trade Organization in 2001, companies from around the world flocked there to set up factories — both to sell their products to a billion newly available Chinese consumers, but also to exploit what at the time were cheap Chinese labor, land, energy, and capital costs, in order to make products for export to the rest of the world. This is known as “platform FDI”.

Poland executed a similar strategy on a smaller scale, becoming a factory floor for European nations — especially Germany — looking for lower costs and more friendly regulation. Malaysia became a center of electronics manufacturing, with investments from the U.S., Singapore, Japan, and elsewhere. In both of these cases, the products of foreign-owned factories were largely sold abroad, since both Poland and Malaysia have relatively small domestic markets. FDI thus helped to make China, Poland, and Malaysia into export powerhouses.

Japan, of course, is in a very different economic situation than China, Poland, or Malaysia were in the 2000s. But it can still learn from their successes. In addition to the direct benefits for investment and employment, greenfield platform FDI offers two main advantages: it can increase a country’s exports, while also facilitating technology transfer. In its current economic situation, Japan could use a whole lot of both of these things.

Japan needs exports

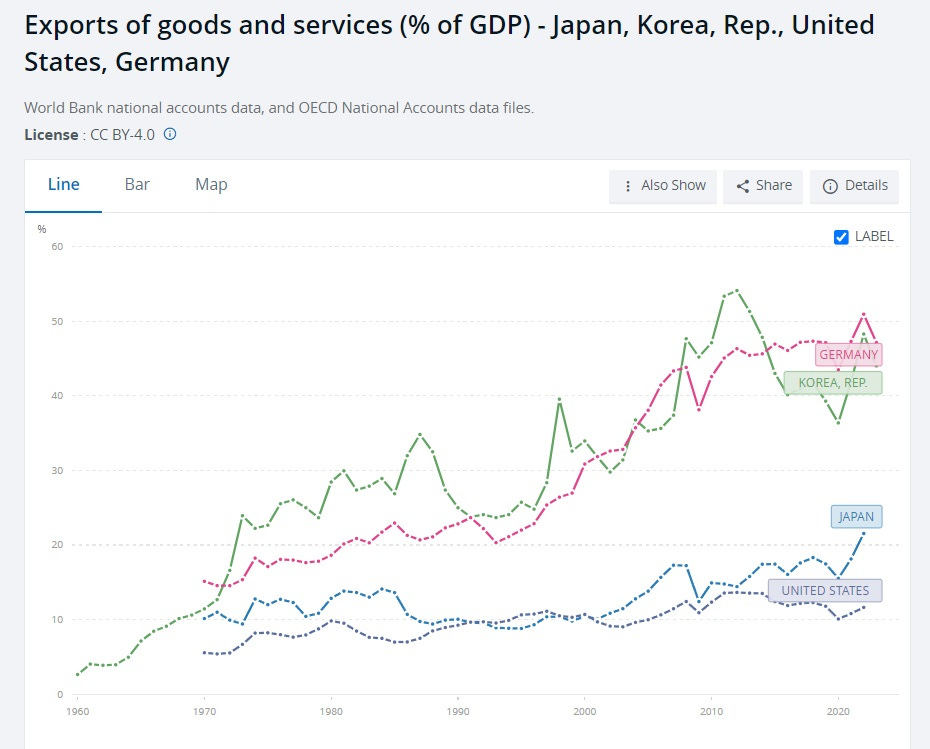

Americans often think of Japan as an export powerhouse, because of the international success of brands like Toyota, Honda, Sony, and Panasonic. And during the early days of the postwar miracle, Japan’s bureaucracy did strongly encourage exports, in order to earn precious foreign currency. But in fact, this lingering stereotype is badly mistaken — Japan has never really been an export-oriented economy like Germany or South Korea. It’s a domestically focused economy, more like the United States:

As Chalmers Johnson recounts in MITI and the Japanese Miracle, this inward focus was part of Japan’s development model in the 1960s. MITI found that ensuring cheap bank loans to domestic companies, and promoting competition in the domestic market, was a way to quickly boost Japan’s investment rate and its capital stock. And they found that this approach also ensured an adequate level of exports, since Japanese companies would produce more than they could sell in the domestic market, and export the excess capacity overseas.

Now, Japan finds itself badly in need of exports. The first reason is that exports help increase the value of the yen, making Japanese people richer as a result.

Japan’s currency has weakened dramatically against the dollar and other world currencies. This is partly because of Japan’s low interest rates relative to other rich countries, which is driven by Japan’s low inflation (and probably by a need to keep Japanese government borrowing costs low, in order to make Japan’s very large government debt sustainable).

As a result of the weak yen, Japanese people are finding it increasingly difficult to afford imports. Japan imports most of its food and energy, so the weak yen is increasing the cost of daily life. Japanese companies are having trouble importing the parts and materials they need, as well as energy. The Japanese government has been forced to intervene to prop up the value of the yen. But such interventions can’t last forever, since they require selling off foreign assets — eventually, the government runs out of foreign assets to sell, and the currency crashes even more.

An increase in global demand for Japanese exports can help increase the value of the yen. This is because in order to buy Japanese goods and services, foreigners need to swap their currencies for yen. This increases the demand for the yen, which pushes up its value. The more exports Japan sells, the stronger the yen becomes. Ultimately, Japan’s currency problem probably can’t be fixed by exports alone — financial outflows will have to be addressed as well. But exports help.

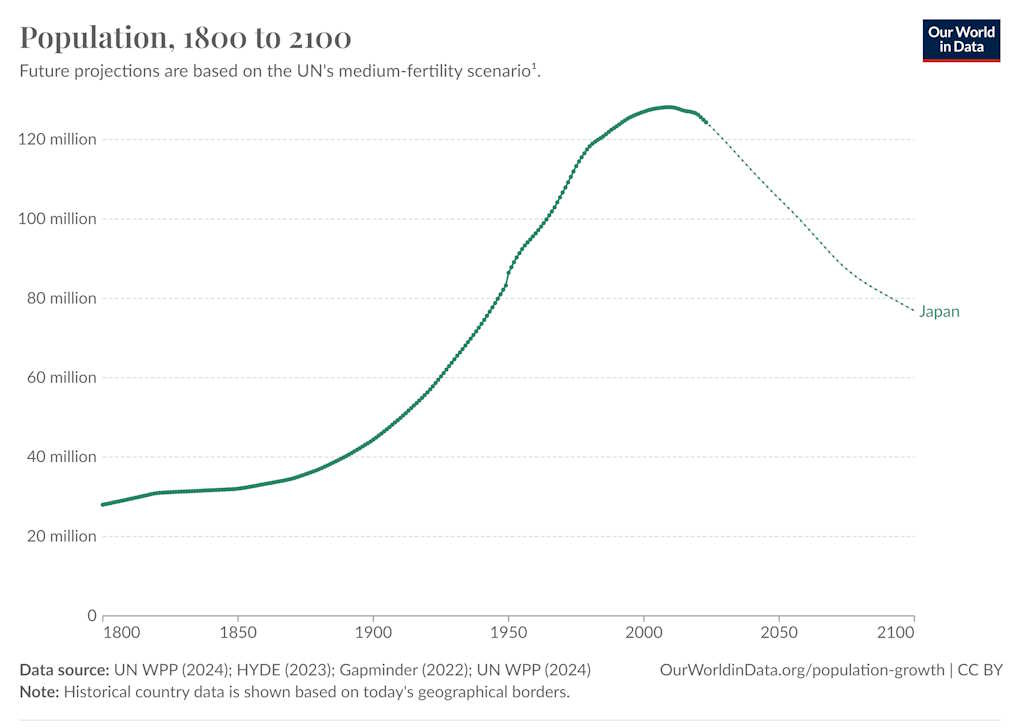

The second reason for Japan to focus on exports is that the domestic Japanese market is shrinking. Japan’s population is forecast to fall substantially over the remainder of this century:

Mass immigration may slow this trend, and measures to increase the birth rate may eventually manage to reverse it. But whether that will ever happen is unknown, and even if it does, Japan will not be a major growth market for a long while. This means there is much less incentive for companies — Japanese or foreign — to invest in Japan in order to serve the domestic market than in the past. Less investment also means less spending on R&D, which causes Japan to fall behind technologically.

Exporting can help reduce this problem, or even solve it. The more Japan becomes an attractive platform for export production, the more reason there is for Japanese companies and foreign companies to invest in Japan, including investments in R&D and new technologies. This will help increase productivity.

Finally, the activities required to increase exports may improve productivity. There’s a lot of research on “learning by exporting” — entering foreign markets could teach Japanese engineers, product designers, and managers how to produce things that foreigners want to buy. This could help counter the so-called “Galapagos syndrome” — the tendency of Japanese product standards to drift away from international standards, shrinking the markets available to Japanese companies.

Another way to put this is that exporting allows companies based in Japan — whether domestically owned or foreign-owned — to achieve scale without exacerbating competition that drives down prices.

Greenfield platform FDI — like TSMC’s fabs in Kumamoto or American venture capitalists’ investment in AI startups in Tokyo — can help Japan become more of an export powerhouse. Okubo, Wagner, and Yamada (2017) find that foreign-owned factories in Japan tend to export more — and also to innovate more. Their explanations for the difference have to do with corporate governance and culture, and with the pool of employees that foreign-owned companies are able to hire. They write:

Foreign ownership may play a role in risk-taking choices of companies – such as exporting and innovating – for various reasons. It can provide companies with more information about the outside market, especially in the context of small and medium enterprises. Foreign owners may be keen on getting high returns on investment and may tolerate a higher risk level. Firms with foreign ownership may have greater access to funds. Also, firms that do allow foreign ownership may experience a more open corporate culture than firms that do not, and such open culture may facilitate risk-taking.

The simplest explanation here is that multinational companies — especially those with foreign employees — simply know a lot more about global markets. TSMC knows what kind of computer chips Nvidia and Apple want to buy. Sakana AI’s founders keep in touch with the American AI market, and understand what kind of capabilities U.S. companies want from AI models. And so on.

In other words, greenfield platform FDI is a perfect example of multi-strategy development. It means that instead of coming into Japan to compete with local companies in the Japanese market, foreign companies are helping Japan sell a bunch of new products to a bunch of new overseas customers.

The intangible benefits of FDI

Japan’s low levels of productivity are somewhat of a mystery to researchers. Nakamura, Kaihatsu, and Yagi (2018), a trio of researchers from the Bank of Japan, arrive at the frustrating conclusion that the biggest problem is a lack of “intangible assets” at Japanese companies. These are any non-physical assets — brand reputation, patents, software, long-term customer relationships, management know-how, worker skills, tacit technical know-how, and so on.

This is such an enormously broad and heterogeneous category, and so many of its components are hard to measure, that “intangible assets” basically ends up becoming a label for economists’ ignorance about what makes some companies more valuable than others. For example, Nakamura et al. note that Japanese companies spend quite a lot on R&D, but don’t seem to get nearly as much value for their spending as U.S. companies do.

So the mystery remains a mystery. But even if we don’t quite know what the most important intangible assets are, we still might be able to help companies get more of them. Nakamura et al. suggest a fairly standard, reasonable list of approaches — increasing labor mobility, improving corporate governance, allowing more lagging companies to fail, and improving the venture capital ecosystem. These are all reasonable approaches, and — as we saw above — they’re all things that Japan is already trying to some greater or lesser degree.

But there’s one strategy that seems to be flying a bit under the radar here: FDI. When foreign companies put their factories, offices, and research centers in Japan, they bring many intangible assets with them — foreign management techniques, technical tricks and know-how, connections to customers and suppliers in other countries, and so on. And these can, for the most part, be pretty easily transferred to Japanese companies.

One way, which has been thoroughly documented by researchers, is through interactions with local suppliers. When a company like TSMC puts a semiconductor fab in Japan, one reason is so that it can buy a bunch of specialized tools and components from Japanese suppliers — like the photoresist that Japanese companies are so famous for. This in turn teaches Japanese suppliers what the leading chip companies need and how to best serve them, as well as details about how the best chipmaking tools work. Those kinds of knowledge are both intangible assets.

Another way ideas spread is through job-switching. TSMC’s fab is going to employ a bunch of Japanese workers. Those workers are going to get the chance to learn how to make chips from the very best in the business. If some of them eventually leave to go work at Japanese semiconductor companies, they’ll take all that knowledge with them. This sort of knowledge transfer would have been harder in the old days, when Japan was still under the lifetime employment system. But now, with mid-career hiring on the rise, it’s very likely.

Let’s imagine an example of how this might work. Suppose you’re a Japanese AI researcher at a domestic AI startup. You and your team know a lot about AI models, from reading research papers, from building them yourself, and maybe from going to some conferences overseas. But for some reason your models aren’t quite as good as foreign companies’ models. The foreigners must have a bunch of little tricks they use to make things work better.

Then one day your company hires another researcher who worked at Sakana AI. Your new colleague knows a lot of those tips and tricks for making models work more smoothly, from having worked with some of the top researchers at Sakana. And their time at Sakana also gave them personal connections with a bunch of other researchers overseas, whom you can now call up and ask for help solving your model’s problems.

Congratulations! You’ve just transferred tacit knowledge for free. Your company’s intangible assets have increased.

If this example sounds contrived, consider how many of Japan’s most famous inventions came through interaction with foreigners and absorption of foreign knowledge. Japan’s Canon cooperated with America’s Hewlett Packard in the 1980s to create laser printers. Yamaha created the digital synthesizer with the help of a Stanford engineer named John Chowning. The famous inventor Sasaki Tadashi licensed American patents to help him invent the first commercially viable pocket calculator.

Those are all examples from the book We Were Burning. In other words, in the 20th century, close links between Japan and the U.S. created a vibrant international research community, where ideas flowed back and forth across borders and across companies.

In fact, there’s evidence that this is a consistent pattern when it comes to FDI. Todo (2006) and Kozo (2006) both find that FDI consistently leads to positive productivity spillovers to the country that receives the investment, and that these spillovers are closely related to R&D spending.

Observers of the Japanese economy have noted with dismay how it seems to be losing human contact with other developed economies. Few Japanese people study abroad these days, and those that do tend to go only for a very short period of time. The number of Japanese young people who want to work abroad has diminished. Collaboration between Japanese scientists and their foreign counterparts has decreased, contributing to a decline in Japan’s high-quality research output. Even as the international research community has grown larger, Japan has been pulling away from it.

Greenfield FDI can help counter that increasing insularity, by bringing foreign researchers and managers into Japan, where Japanese people can absorb their knowledge without leaving the country.

Japan is welcoming the right kind of FDI, but it can do more

Why has greenfield FDI in Japan traditionally been very small? In the early days of its postwar miracle, Japan restricted all kinds of FDI for protectionist reasons, in order to reserve the domestic market for Japanese companies that were still in their early growth stages. This was a typical policy for the time, and not dissimilar from the “infant industry” protections used by the U.S. in its early development.

From the late 1960s through the early 1970s, Japan significantly liberalized its restrictions on FDI. There were still many institutional barriers to foreign acquisitions, mostly resulting from a combination of Japan’s financial and corporate governance systems, and from cultural resistance. But although foreign companies should, in theory, have had an easier time doing greenfield M&A from the 1970s onward, few took the plunge. There are lots of possible reasons for this — force of habit, regulatory differences between countries, cultural differences, and a general stereotype of Japan as a protectionist economy. But the most important reason was probably that unlike countries like China, Poland, or Malaysia, Japan simply didn’t try to actively encourage foreign companies to use it as a production base.

Since 2003, though, the situation has slowly changed. Former Prime Minister Koizumi Junichiro called for more FDI into Japan. Regulations were eased a bit, and tax incentives were put in place. These efforts were minor and halting at first, but have gathered strength over time. Targets have become much more ambitious — in 2023 the government set a goal of attracting 100 trillion yen of FDI (about $690 billion as of this writing) by 2030. Politicians now talk regularly about the need to boost FDI. Immigration laws have been changed to make it much easier for skilled professionals to get permanent residency. There is a new Council for the Promotion of Foreign Direct Investment in Japan, and various other government efforts to attract FDI.

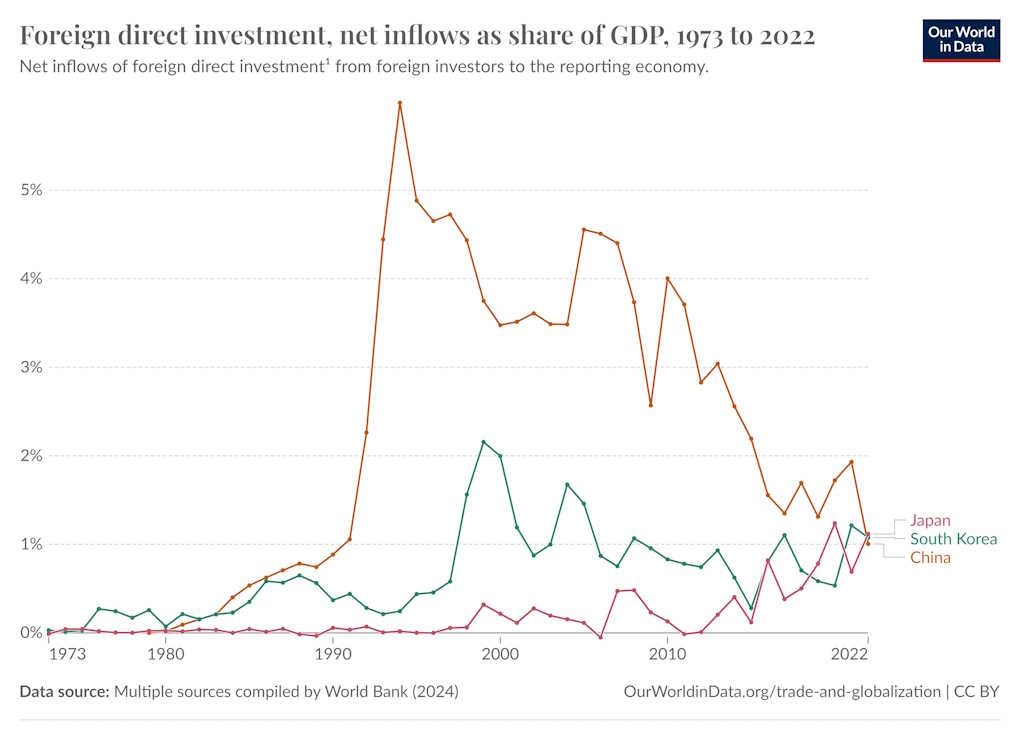

And amazingly, the plan seems to be working. In 2022, net FDI inflows to Japan were very slightly greater as a proportion of the economy than in either China or South Korea:

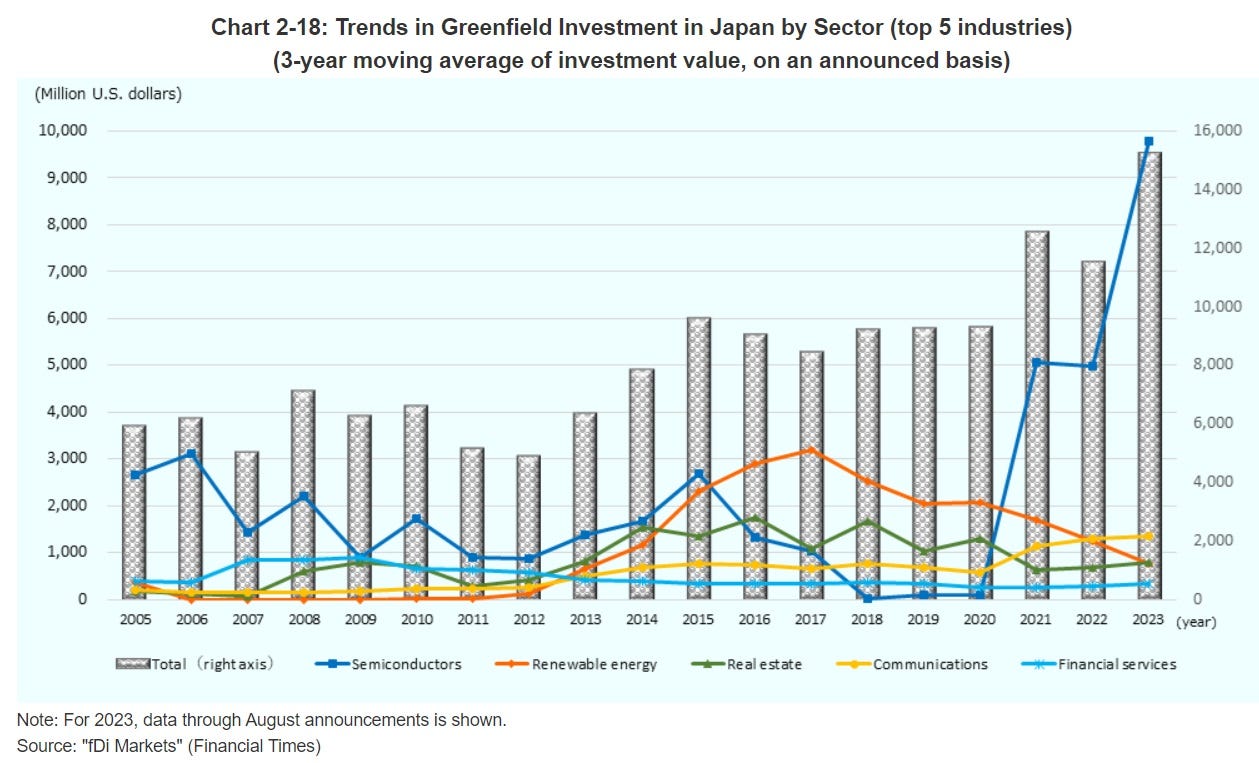

And encouragingly, greenfield FDI seems to be powering this rise. The number of inbound M&A deals has held steady, while greenfield projects have soared:

And since the semiconductor industry is powering this rise, it’s likely that a significant amount of this will result in exports.

But although this is good progress, Japan could do a lot more on the FDI front. First of all, 1.1% of GDP per year is a big improvement, but it’s not really big enough to be transformational — Poland gets over 5%, France gets 3.8%, and the U.S. gets 1.5%.

Second, most of Japan’s greenfield FDI is in one single industry — semiconductors. If Japan could attract similar levels of investment in other sectors, it would be insured against a sudden downturn in the chip industry, and it would have the chance to build up its technological muscle along a wider front. There are plenty of other high-value industries where Japan could be a high-tech, low-cost production platform — aerospace, biopharma, batteries, and electronics being four obvious examples.

In other words, Kumamoto, Sakana AI, and the other examples above are an important proof of concept for a golden age of Japanese FDI, but they should be only the beginning.

Why do foreigners invest in Japan?

Traditionally, the reason a few foreigners wanted to invest in Japan — either through greenfield investments or M&A — was to tap the large and lucrative Japanese market. That motivation still remains to some extent, but it’s growing weaker every day. But there are a number of reasons Japan is increasingly attractive as an export platform. Understanding these reasons is absolutely crucial for Japanese government officials and businesspeople who want to attract more FDI — if you’re selling something, you must understand why your customers want to buy it.

The most obvious selling point is the weak yen. A cheap Japanese currency makes anything produced in Japan more competitive in world markets. On top of that, decades of stagnant real wages have a silver lining — they’ve made Japan’s skilled workforce look relatively cheap. A third strong point is Japan’s deep network of high-quality suppliers.

There’s also the national security angle. As China’s foreign policy has become more aggressive, the U.S. and other developed nations have begun to try to move them out of China. The U.S. government calls this “friendshoring”, while companies call it “de-risking”, but the principle is the same — no one wants to be caught dependent on Chinese manufacturers for critical high-tech products if a war breaks out. Japan is an obvious alternative production base — it’s smaller and more expensive than China, but infinitely more secure. And unlike China, Japan will not use espionage to steal foreign companies’ intellectual property.

Even Germany, which has traditionally been more willing than other Western countries to invest in China, is beginning to get nervous; a significant number of German companies are looking to switch to Japan. And the U.S. Department of Defense is planning to develop advanced weapons in Japan, as well as manufacturing more traditional munitions there.

Yet another advantage — which Japanese people may not fully appreciate, since they’ve never had to deal with the alternative — is Japan’s efficient government. In many Western countries, environmental review laws and other poorly crafted regulations have turned land use into a nightmare — projects that pass all relevant environmental and safety regulations still have to endure years of lawsuits and court-enforced paperwork, making it hellishly expensive and time-consuming to build factories. The U.S., the UK, and other anglophone countries, which rely on the courts to adjudicate environmental regulation, have become especially hostile to development.

Japan’s more sensible and efficient system, which relies more on bureaucrats than on the court system, preserves some role for community input, but allows construction projects to be approved in a timely manner. Japan’s willingness to build, meanwhile, has left it with plenty of high-quality infrastructure — and the ability to create more quickly to suit the needs of foreign investors if necessary.

But there’s one more huge reason that foreigners want to invest in Japan, which could ultimately be more important than all the rest combined. And it’s a factor that, in my experience, very few Japanese people — including the government officials tasked with promoting FDI — yet appreciate.

The key is that people around the world really love Japan, and want to live there.

(In Part III, I’ll explain why so many people in the world want to live and work in Japan — and how Japan can leverage this soft power to supercharge its FDI sector.)

To emphasize one of your important points:

"Second, even failed startups often contribute crucial innovation to a country’s ecosystem. Fairchild Semiconductor wasn’t successful, but it pushed the envelope of semiconductor technology forward, and some of its alumni went on to found Intel. General Magic tried and failed to invent the smartphone in the 1990s, but its alumni went on to help create the iPhone."

Failure is an important part of the path to success creating both technical expertise and adjacent technology & capabilities that enable future successes. This is true both when the future success is internal and external to a company.

I'm going to stand firm on my position that non-anglophone countries are only notionally pro-AI because the penny hasn't dropped yet. I find it very hard to believe that the same cultural landscape that has delivered the current Japanese software culture will react to the real effects of AI in any way but abject horror.

I bring one item of evidence. The absolutely NUCLEAR reaction of the Japanese localization community of Mozilla to the introduction of AI translation.

"I prohibit to use all my translation as learning data for SUMO bot and AIs.

I request to remove all my translation from learned data of SUMO AIs."

https://support.mozilla.org/en-US/forums/contributors/717446