What should China do to revive its economy?

There are a couple of aces that the government hasn't yet played.

OK, I know I said that the previous post in my China’s Economy in 2023 series would be the last one, but I just can’t resist writing one more. In the earlier posts I talked mainly about structural long-term issues, but I really should write something about the macroeconomic situation.

Everyone is talking about China’s economic slowdown. China’s headline growth for the second quarter is being reported at 6.3%, which sounds really fast, and which the country’s boosters have been trumpeting as a sign that China Is Back. But economics writers aren’t being fooled; they know this is a year-on-year figure, and represents a comparison with the darkest days of Zero Covid. In fact, China’s quarterly growth rate was 0.8%, which represents a 3.2% annualized rate of growth:

3.2% isn’t that bad; it certainly isn’t a recession. The question is whether or not even that modest number reflects reality. We have plenty of evidence that China smooths its growth numbers over time; when the economy is slowing down, “smoothing” just means “overstating”. And of course China has become a lot more cagey and secretive about its economic statistics in the last couple of years, and its leaders want to avoid the perception of economic weakness, so there’s a high likelihood that the real growth number is significantly worse than 3.2%.

Other numbers generally corroborate that story. China’s youth unemployment has risen from 11% or so before the pandemic to over 20% now, exports and imports are both falling, and the country appears to be heading for deflation if it isn’t there already:

The reason for this downturn — whether or not you want to call it a “recession” — is clear to pretty much everyone. It’s the real estate sector, which has been China’s biggest economic engine since at least 2008, and which has now mostly ground to a halt after a bunch of developers blew up.

Whether this is a bad thing for the rest of the world isn’t yet clear. On one hand, China used to be the largest contributor to global economic growth, and at least until recently was expected to be this in the 2020s as well. On the other hand, a collapse in Chinese demand for imported commodities has helped lower inflation around the world, and the diversion of international investment from China to other countries could give them a boost.

But either way, China’s policymakers will certainly be looking for ways out of this downturn. So far, the main ideas being suggested are basically the tools the U.S. used to fight its own housing-driven crash in 2008: fiscal stimulus and a central government bailout of bad debts.

Stimulus and bailouts

The economist Richard Koo was one of the intellectual heroes of the Great Recession. Having carefully watched Japan’s bubble bust and “lost decade” in the 1990s, he came up with the idea of the “balance sheet recession”. This is the idea that when a recession follows a big borrowing binge, households and/or companies stop borrowing and start trying to “rebuild” their balance sheets. Of course if everyone tries to save money all at once, it means people stop consuming and companies stop investing. That exacerbates the recession.

Koo’s analysis isn’t very different from traditional Keynesian economics, but it assumes a specific type of what Keynes called “animal spirits”. Basically, it’s the idea that when the economy gets weaker, people are more sensitive to debt. Maybe when it’s 2006 and everyone is seeing their house prices go way up, you don’t mind having a bunch of debt because you expect price appreciation to pay it off for you, or maybe you’re just having so much fun you’re not really paying attention to the “liabilities” side of the ledger. But when it’s 2010 and your house is underwater, maybe you go into financially-conservative mode and decide that you had better pinch every penny you can. There are lots of reasons people could behave like this — extrapolative expectations, limited attention, time-varying credit constraints, or various other reasons. But the evidence generally favors the idea that downturns with a bunch of debt are deeper and last longer.

And the basic policy recommendation is the same: to fight a recession, make people and companies feel financially healthy again. This means either bailouts and/or fiscal stimulus — either have the central government explicitly take on the debts of various other actors in the economy, or have it spend a bunch of money that people can use to pay down their own debts.

(Note: This is a little different than standard Keynesianism, which recommends fiscal stimulus as a way to jump-start spending activity via multiplier effects. In Koo’s modified version, stimulus helps even if the multiplier is low; even if people just save their government checks instead of spending them, that will help repair their balance sheets and eventually make them more confident about spending more.)

So anyway as you might expect, Koo is suggesting that China do both stimulus and bailouts. This is from his interview on the Odd Lots podcast:

[T]he private sector themselves cannot change their behavior -- after all, they're doing the right things: trying to repair their balance sheets -- then the government has to come in and borrow and put that money back into the income stream, which means fiscal stimulus is absolutely essential once you're in balance sheet recession.

Now, the basic macroeconomic argument for stimulus looks pretty strong. Rising youth unemployment and deflation both suggest a lack of aggregate demand, which is the typical Keynesian reason for stimulus. Chinese households have boosted their savings rates in recent years, suggesting a Keynesian “paradox of thrift” is going on. And China’s high amount of private-sector debt — substantially higher as a share of GDP than either the U.S. or the Eurozone — suggests that the central government could afford to assume some of this debt.

China certainly has the fiscal “space” to do massive stimulus and/or bailouts. Its central government debt to GDP ratio is only around 80% of GDP — about where Japan’s was at the start of its lost decade, and much lower than where the U.S., Japan, or most of Europe are today:

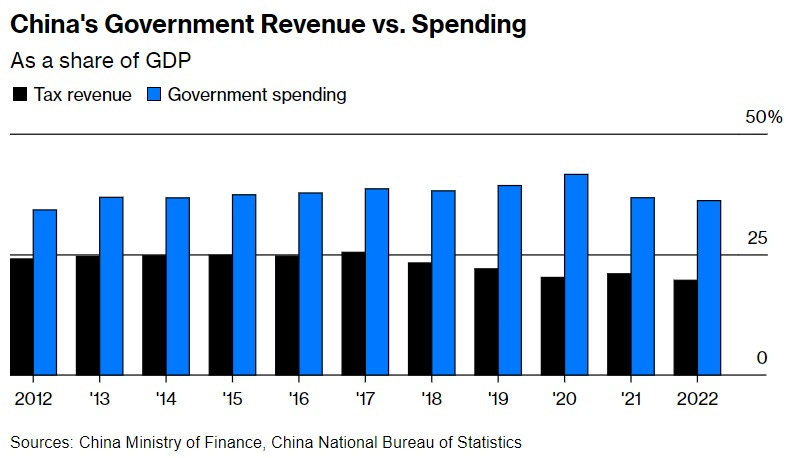

But a couple points here. First, China is a very low-tax country. Taxes were less than 20% of GDP in 2022, compared to about 33% in Japan and 27% in the U.S. And that number has gone down in recent years:

If China’s central government does stimulus, it will either have to raise taxes or accept a very large, very rapid runup in government debt. Raising taxes could be politically quite difficult, and there’s also eventually some limit to how much debt the central government can take on before economic problems start emerging. So these will hamper China’s attempts to do big sustained stimulus. This probably explains the general skepticism about whether China will take this route.

Next, it’s far from clear that stimulus will make China avoid Japan’s fate. Koo writes:

And so my guess is that Chinese government will put in the fiscal stimulus, which they're actually quite good at, and that will keep the recession from turning into a depression or something. So that's the key difference between the Japanese situation 30 years ago and what the Chinese may be faced with today…

But if you look at the chart above, you can see that starting in 1993, Japan started to run very large and very sustained fiscal deficits. And in fact those deficits are probably one reason why Japan avoided a large increase in unemployment during its “lost decade”. Japan’s stimulus was macroeconomically successful. It just didn’t stop Japan from becoming “Japanified”. So I’m not sure we should expect even a large Chinese stimulus to achieve significantly better results.

Some people argue that because Chinese property prices aren’t actually plummeting — as Japanese commercial real estate prices did in the early 90s — that China can avoid Japan’s fate. And maybe that’s true — if credit constraints are the reason for balance sheet recessions, then maybe having real estate that’s still worth a lot on paper can help avoid the economic harms of a debt hangover.

But I have my doubts. At this point, Chinese people no longer think of real estate as an asset that always goes up in price. Even if prices don’t plummet, the extrapolative expectations are gone; most people know that the only way to avoid selling their houses at a big loss will be not to sell at all. And if you can’t sell an asset for cash, what’s it really worth?

Japan comparisons aside, there’s the question of what China would actually spend stimulus money on. Koo suggests that China’s government spend money on completing the uncompleted houses that have made lots of people so mad:

I would recommend Chinese government to go in there and help those construction companies so that all the promised construction will be actually completed. I think that will be the most effective way to spend fiscal stimulus, fiscal money.

This might be a good idea, but it would be pretty small potatoes. China was estimated in 2022 to have up to 225 million square meters of unfinished homes (though some of that has probably since been completed or scrapped). That sounds like a lot, until you realize that it’s only 15% of Chinese housing construction in 2021, and less than 7% of the total number of unsold homes China already has sitting on the market.

There are also several big problems with the general idea of using stimulus to prop up the real estate industry. This is what China did again and again throughout the late 2000s and 2010s; when Koo says China’s government is “actually quite good at” stimulus, this is what he’s talking about. But those years of real-estate-focused stimulus came with major costs — in particular, a massively bloated real estate sector and slower productivity growth.

So trying to go back to that well once again might cement China in the dread middle-income trap.

Second, China’s ability to use real estate as stimulus was predicated on the expectation that prices would always go up, which created ever-greater demand for the new apartments that were being pumped out. That’s probably gone now; China has reached developed-world levels of floor space per person, and Chinese people have now spent a couple years watching prices drift downward. So the extrapolative expectations that motivated whole families — eight grandparents, two parents, and a young couple — to pool their life’s savings to buy a single urban apartment have probably been destroyed.

In other words, having the central government borrow a large percentage of GDP and hurl it at the housing market will probably not be a very effectual form of stimulus.

The other big suggestion I’ve seen is to have the central government use stimulus money to bail out local governments, which ran up a ton of real-estate-related debt. I don’t see the point of that. China’s local governments have a lot of debt because they don’t do property taxation, so bailing them out will not allow them to start spending more, now that land sales revenues have dried up. Instead, China’s government can (and probably will) take over some of the day-to-day funding of local governments, though this will require raising income taxes or sales taxes or some such.

Instead, what China should do is just have the central government cut a bunch of checks to Chinese households. If they went out and spent the money, good — that would deal with the aggregate demand problem. And if they used the money to pay down their debts, also good — that would help deal with the balance-sheet problem.

I’m not sure whether China’s government feels comfortable dropping money out of a helicopter, but it seems like the best way to give their economy a short-term boost.

But there’s one more big thing I think China can and should do.

Might as well build a world-class health care system

Some people argue against using a short-term macroeconomic crisis as a reason to undertake needed long-term structural reforms. I don’t see the point of that argument. If there are reforms you need to make anyway, and if they involve spending more government money, then a recession seems like a perfect time to do them.

In China’s case, the reform it needs is a world-class health government-funded health care system. China still spends very little of its GDP on health care compared to advanced economies:

Although China nominally has universal health coverage, it’s actually pretty patchwork and subpar:

Since 2016, the two main [Chinese health insurance] programs covering 95% of population are voluntary, residency-based, basic medical insurance; and mandatory employment-based program for urban residents with formal-sector jobs…Although China has universal coverage, it has a very entrepreneurial, unregulated healthcare system which led to some gaps in the system…

The health system is conflicted between stressing quality of care or spreading the scarce medical resources as widely as possible. As evaluated on a per capita basis, China’s health facilities remain unevenly distributed. Only about half of the country’s medical and health personnel work in rural areas, where approximately three-fifths of the population resides. The severest limitation on the availability of health services, however, appears to be an absolute lack of resources, rather than discrimination in access on the basis of the ability of individuals to pay. An extensive system of paramedical care has been fostered as the major medical resource available to most of the rural population, but the care has been of uneven quality.

Basically, China’s health care system isn’t great because they just don’t spend very much. Well, time to spend more. A massive program of government spending on health care would work as fiscal stimulus even as it also fixed one of the most glaring holes in the Chinese economic model.

It would also deal with that pesky youth unemployment problem. Health care is one of the most labor-intensive industries, so in terms of providing jobs for youngsters, it makes a good replacement for the anemic real estate industry.

It’s also something China is just going to have to do anyway. A huge cohort of Chinese people in their 50s is about to enter old age:

Without a world-class health care system, the burden of caring for these old folks when they get sick or disabled is going to fall on young workers. That eldercare burden will draw young healthy people (especially women) away from productive work, and force them to spend their time doing tasks for which they are not specialized. Which will starve Chinese companies of needed labor and reduce potential growth.

Building a world-class health care system could avert this fate. Maybe the Chinese government won’t do this; maybe Xi Jinping thinks that health care is weak and decadent, and that Real Men (TM) work in factories or construction sites. But what America’s New Dealers realized is that if you lower the amount of time that young people have to spend taking care of grandma and grandpa, you free up young people for more productive work. China would be wise to follow that example. And an economic downturn is a perfect chance to do this.

So those are my two suggestions for China to get its flagging economy on its feet: Cut big checks to households, and rapidly build out a top-notch government-funded health care system. Those will both require spending a lot of central government money, and — eventually, not right now — raising taxes to developed-world levels. But the alternative is to experience a protracted downturn as real estate prices go sideways for a decade and economic pessimism becomes entrenched. And spending money on consumption and health care will yield a lot more bang for the buck than hurling it directly into the maw of the real estate mess. Either way, Chinese growth is going to slow down going forward, but I think my two suggestions would make that transition a lot less painful.

China having lower taxes than the USA and Japan is…news to me. I’m surprised for some reason but not sure why.

I noticed that mass media usually report *youth* unemployment for China, whereas for other countries an *overall* unemployment is typically reported. That is also the case in this blog. Is there a reason for this? Shouldn't we be comparing apples-to-apples