What does China have to lose from a real estate crash?

A lot.

This is part of an ongoing series about developments in China’s real estate market. Previous installments in the series:

China’s real estate trilemma (subscribers only)

Hexapodia XXVII: Evergrande (podcast with Brad DeLong)

Why China's Evergrande Crisis Could Be Worse Than the U.S. Crash (Bloomberg Opinion)

Chinese real estate is still in the news, as the Evergrande saga continues. A lot of the coverage has focused on the company itself, which may or may not have already defaulted but is certain to do so soon. People are looking at Evergrande in order to get an idea of whether there’s going to be contagion to other real estate developers or to the Chinese economy as a whole, what the government’s response will be, etc. But my sense is that at this point, the details of this one company’s situation matter less and less for the systemic picture. Even if the company manages to bamboozle bondholders into thinking they’re going to get repaid for another week or another two months, global uncertainty about the Chinese property market and its related industries is already on the rise, Chinese growth forecasts are being downgraded, Chinese and global asset markets are reacting negatively, and the Chinese government is already in crisis management mode. This is already much bigger than Evergrande, and everyone knows it.

Which does NOT mean there will actually be a real estate collapse in China. MacroPolo analyst Houze Song believes that the government will do what it takes to sustain the property sector, at least for a while longer:

We believe that Evergrande is an exceptional case that is unlikely to lead to a broader systemic crisis in the property sector…This near-term baseline scenario is predicated on three key factors: 1) the central bank will further relax mortgage policy to alleviate the liquidity crunch for the property sector; 2) property sales will rebound as demand for housing remains healthy; 3) the more vulnerable firms will be able to sell their assets (e.g. land) to raise cash…

Since Beijing, and Xi Jinping personally, have long emphasized a stable property sector as a precondition for any macro policy, the PBOC’s recent hawkishness will have to be moderated…

The fact that property demand appears to be holding up despite the recent turmoil further suggests that a reversal of the broader clampdown [on real estate] can go a long way toward assuaging concerns.

(By the way, in case you’re wondering who I turn to for China analysis, the think tank MacroPolo, and its founder Damien Ma, are a favorite source of info. Damien’s 2013 book about China’s economy successfully predicted much of what has happened between then and now.)

So the bull case is that China’s leaders are going to stare into the abyss of a real estate crash, decide it’s not worth it, and pull back, using a combination of monetary policy and state-directed lending to reflate the sector. This is basically what they’ve done the last few times a crash threatened (in 2009, 2014, and 2016), so it seems like there’s a reasonable possibility of it happening again.

The bear case — at least, in terms of investment in the sector — is that the Chinese government is serious about moving the economy away from real estate, construction, finance, and so on. Evergrande’s collapse was precipitated by new government restrictions on real estate and tightening by the central bank. The government telegraphed its intentions by declaring that “Housing is for living in, not for speculation.” And Xi Jinping has shown a determination to shift the economy away from industries like real estate and finance and toward manufacturing.

It’s possible that Xi will stay the course, accept a temporary slowdown in economic growth (perhaps papering over it with a year or two of creatively reinterpreted government statistics), try to make political opponents and foreigners bear most of the financial losses, and use the crisis as an occasion to tighten government control over the economy — all with the expectation that productivity and growth will eventually rise once resources shift out of real estate.

Either of these narratives will please the people who think that China’s government always has everything under control. If the government bails out real estate yet again, then it will be praised for maintaining stability; if it goes through with a wrenching transformation, it will be praised for boldly shifting the economy toward a less unbalanced, more productive model.

These claims will be strengthened by the fact that China, unlike America in the 2000s or Japan in the 1990s, has a state-controlled banking system that will not collapse if the government does not allow it to collapse. China can bail out the banks, or simply ignore their solvency and tell them to keep lending. And those loans will sustain the economy. When China avoids a U.S.-style or Japan-style collapse in lending, it will be hailed as evidence that China has figured out a better way to manage an economy.

But that doesn’t change the fact that China is in great danger from a real estate crash. The dangers are simply different than for a market economy — or even for a socialist economy that lacks China’s distinctive characteristics. Here are four of the ways I think China will suffer from a real estate crash — even if there’s no severe recession.

Danger #1: A shift toward even less productive assets

Xi seems to want to reorient China’s economy toward the creation of national power, which in his mind involves more manufacturing and less real estate. But unproductive manufacturing companies — pumping out product at a loss — are not a good route to national power, as both the Soviet Union and China under Mao discovered.

In the long run, it’s probably possible to reorient China’s economy from real estate, construction, and finance to manufacturing in a way that enhances productivity. But this will take time. Entrepreneurs have to figure out their comparative advantage and build effective organizations. Communities of engineering practice and managerial talent must develop. Market niches must be sought out and exploited. And the requisite technology must be imported or invented. Even when this is successful, it tends to take a decade to make a major shift like this, as South Korea’s Heavy Chemical and Industry drive demonstrates.

If China has a crash in the property, construction and finance industries, and if Xi wants to avoid a recession, he doesn’t have a decade; he has perhaps a year. In that time he must direct banks to seek out and find manufacturing businesses to lend to whose output equals the lost output from real estate. And this task will be especially gargantuan in China, where real estate and related activities comprise almost 30% of the economy:

And as Brad and I point out in our latest podcast, China might have trouble sustaining the economy by pumping up exports, as the U.S. did to some degree after our housing crash. The world has grown more leery of Chinese exports, and much of the available market has already been exploited due to Covid, which knocked out some of the competition. So if China tries to replace real estate with manufacturing overnight, it may be forced to make things that no one anywhere really wants.

In fact, some of this has already happened in China’s past rounds of stimulus. Cong, Gao, Ponticelli and Yang (2016) show that when the government increased bank lending after the Global Financial Crisis, the portion that went into manufacturing tended to go to lower-productivity state-owned enterprises, causing a reduction in productivity growth.

Americans are often sympathetic to Xi’s desire to shift China’s economy away from finance and real estate, since we remember how much of our own talent was siphoned off into those industries in the 2000s. Heck, I’m sympathetic too! But industrial policy isn’t quite like squeezing a tube of toothpaste — you can’t just squeeze one sector and expect resources to come out somewhere else. Developing new industries well takes time; otherwise the result could be further stagnation in productivity, and a Middle Income Trap sort of situation.

Danger #2: Loss of stabilization policy

A closely related danger — and one that outside observers may fail to appreciate — is that forcing a shift away from real estate could rob China of its macroeconomic stabilization policy.

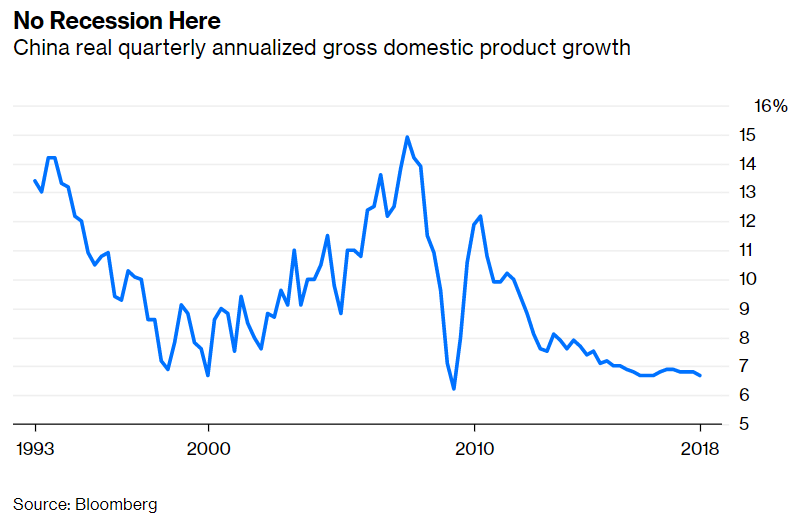

China has gone many years without a recession (at least on paper; the jury is still out on whether it had to cook the books a little to keep growth positive in the Asian Financial Crisis and the Global Financial Crisis).

China was able to do this for two reasons. First, it had plenty of room left for rapid catch-up growth, as long as it was able to sustain aggregate demand. But second, it had a very special tool for sustaining aggregate demand: State control of the financial sector. Whenever a macroeconomic threat loomed, China could simply tell the banks to lend a bunch of money in order to keep growth going.

There is plenty of interesting research on how this system worked. A couple examples:

Acharya, Qian and Yang (2016) show how Chinese pressure on big banks to lend during periods of macroeconomic instability increased loans, and also ended up pumping up the shadow banking industry, as smaller banks were forced to compete. They document how much of this flowed into the property sector.

Bai, Hsieh and Song (2016) document the size of the financial stimulus and the role of local government financing vehicles (which are mostly invested in real estate and related activities).

If Xi stays the course and decides that this sort of thing holds China back, then China loses this superweapon against recessions. It can still tell banks to lend to manufacturing companies, but again — remember, as Cong et al. (2016) showed, this tends to funnel money to low-productivity SOEs.

Which means that the tradeoff between short-term growth and long-term productivity wouldn’t just be this time; it would be forever. China’s near-magical ability to bat away macroeconomic threats while sustaining relatively rapid growth would be gone.

Of course, this was probably going to happen anyway. As China reaches developed-world levels of floor space per person, demand for real estate was always going to eventually flag, meaning that using real estate lending as stimulus would also incur a drop in productivity. But if MacroPolo’s analysis is right, there’s still enough demand for housing that the policy could be maintained a little longer if the government chooses.

Danger #3: Household wealth destruction

The previous two dangers have to do with long-term productivity growth. But there are also threats to the wealth of various actors in China. Because China’s stock market is not very well-developed, and because deposit rates are kept low, middle class wealth is mostly invested in property or in property-related products. This can include:

Owning property

Holding wealth management products backed by bank or shadow bank investments in property or construction

Holding local government bonds implicitly backed by local governments’ ability to sell land to raise money

Holding bonds from construction companies or developers

Etc., etc.

A commonly cited estimate is that 70% of the wealth of urban Chinese households is in real estate, but much of the rest is in financial assets that themselves are often heavily tied up with real estate. Thus, if real estate values and the value of related companies decline heavily, the newly emergent Chinese middle class is going to take an enormous loss — depending on the size of the bust, probably bigger than the devastating and lasting losses American households took after 2008.

Will that cause widespread unrest and disaffection with Xi’s regime? I would expect so. But since Xi is ultimately supported by the Chinese Communist Party, an even bigger factor might be the losses taken by the 95 million Party members — most of whose wealth is almost certainly also dependent on real estate in one way or another. Obviously Xi will arrange things so that his friends and allies within the Party get to keep the real estate and related assets that hold their value, while sticking political enemies with the assets that go to zero. But the real question is how many “friends of Xi” there are and how many get left on the outside. Selectorate Theory says that if you piss off too many of the people who hold real power in a country, you get the boot — so the question is whether a bust will still leave Xi with enough good assets to pay off a winning coalition.

Danger #4: Local government financing crisis

Local governments in China tend to fund a significant chunk of their spending by selling land. Obviously that can’t go on forever, and the central government has been trying to push the local governments toward more traditional tax-based financing. But a real estate crash will forever damage local governments’ ability to raise cash in the way they’re accustomed to doing.

The central government can (and probably will) bail out local governments’ bad real estate related debts. But going forward, less activity in the sector, and less demand for LGFV debt, will force local governments to shift to financing themselves with taxes; already, land sales by local governments have plunged significantly. This shift could crimp economic activity, and lead to a diminution of the local governments’ power and prestige — angering the Party cadres upon whose support Xi depends.

The end of the China Model?

So there is a real danger from a rapid and permanent shrinkage of the Chinese real estate sector, even if the country manages to avoid a financial crisis and recession of the type that capitalist countries tend to suffer after property busts. In China’s case, the danger is more long-term — a slow-motion collapse of the growth model that has seen the country catapulted from poverty to middle-income status in just 30 years.

In fact, that model has already undergone significant evolution, with a transition from export-led growth in the 90s and early 00s to domestic investment-led growth in the late 00s and 10s. The long boom in real estate and construction was bound to end eventually, but the unwinding precipitated by Evergrande’s collapse, combined with Xi’s determination to shift the economy toward industries he likes better, threaten to end China’s most recent growth model in a premature, suboptimal fashion — and one that leaves lots of influential and important Chinese people jilted out of their expected fortunes.

No country can sustain rapid growth forever, and to transition from fast growth to slow growth without a devastating recession is quite an accomplishment. But a recession isn’t the only kind of scar that the transition can leave. If Xi insists on a hard and permanent landing for Chinese real estate, he could easily end up with a weaker country and a bigger backlash than he expects. That’s a strong argument for reflating real estate and slowing Xi’s plans for a rapid industrial shift.

I'd really like to see that graph of the real estate sector as a % of the economy pushed back another decade or so, to see what Japan looked like in the Crichton-panic era.

The party doesn't think it can afford a recession. So they're making the bet that they can reduce reliance on unproductive sectors without letting companies fail and their stakeholders suffering economic consequences. But that creates the same moral hazards that allowed those sectors to become so prevalent.

Maybe they can thread the needle. Maybe they can't. I suspect the task is too delicate and complicated, but might be wrong.