The Pettis Paradigm and the Second China Shock

Will tariffs help rebalance the global economy (and the Chinese economy)?

Wow, two China-related posts in two days! This one is going to be less dire and more wonkish than yesterday’s, because it’s about China’s economy and the international trade situation, instead of about war and conflict. (The two aren’t entirely unrelated, of course.)

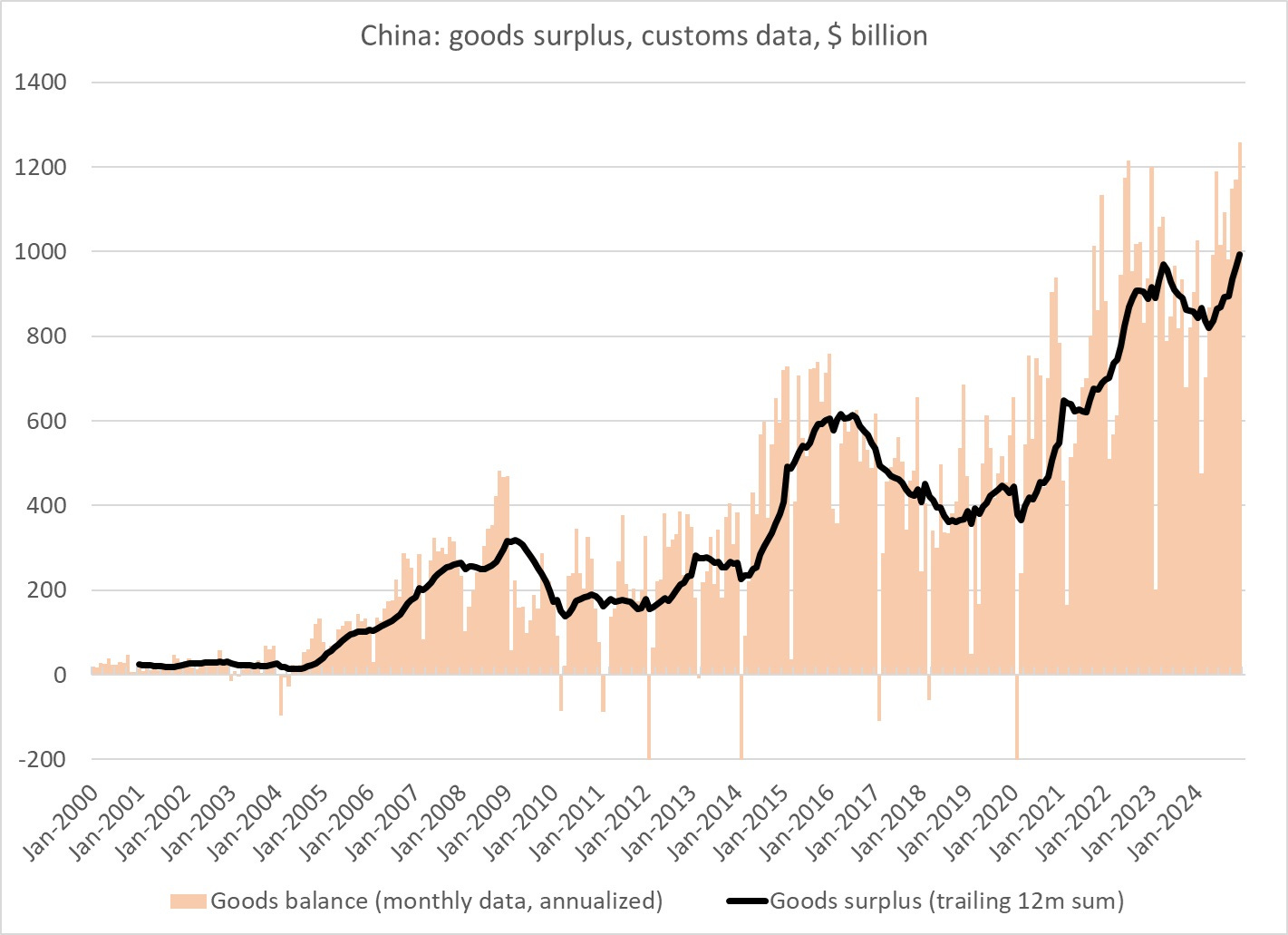

China has a huge and growing trade surplus, as you can see in the chart above. That chart is via Brad Setser, who is really a one-man army in terms of tracking global trade and financial flows. Here’s a thread from Setser with a lot more detail on China’s surplus. Interestingly, China’s exports to the developing world are a lot bigger of a factor here than its exports to the U.S. and the EU, though the latter are up by a little bit.

This is the Second China Shock. Trade surpluses like this can’t be explained by the good old theory of comparative advantage — a Chinese trade surplus is just countries writing China IOUs in exchange for physical goods. Countries don’t really have a comparative advantage in writing IOUs.1

Why trade surpluses and deficits do happen is an important and interesting and complex question, and my general impression from reading a bunch of economics papers on the topic is “No one really knows”. It probably has something to do with the fact that China’s government is directing its banks to loan vast amounts of money to manufacturers, and paying manufacturers tons of subsidies on top of that. But there also has to be some sort of financial factor involved that prevents China’s currency from appreciating and allowing Chinese people to buy more imports. This could be something the Chinese government is doing intentionally, or it could be a natural outgrowth of China’s economic difficulties. More on this later.

The question is what to do about the vast flood of Chinese exports. Overwhelmingly, from all sides of the commentariat, there has been one main policy proposal2 for the world outside of China: tariffs on Chinese goods. The MAGA people, obviously, endorse this — tariffs are one of their big policy ideas.

In addition, some commentators suggest that China should shift its economic model toward promoting domestic consumption instead of yet more manufacturing. Many of the people suggesting this are private-sector macroeconomists who work for banks, writers, or other private-sector analysts. But notably, Paul Krugman has said similar things. Many commentators who don’t explicitly endorse tariffs will nevertheless say that if China doesn’t shift toward consuming more of what it produces, the world inevitably will put tariffs on Chinese goods.

The “other countries should put tariffs on China” idea and the “China should shift its economy toward domestic consumption” idea are unified in the worldview of Michael Pettis, who has advocated both things. He has been saying that China needs to increase the share of consumption in its domestic economy for well over a decade, and it seems to me that more than anyone, he is responsible for injecting this idea into the discourse. And in an article in Foreign Affairs in December, Pettis laid out a case for tariffs:

Today, [unlike in the 1930s], Americans consume far too large a share of what they produce, and so they must import the difference from abroad. In this case, tariffs (properly implemented) would have the opposite effect of [the] Smoot- Hawley [tariffs of the 1930s]. By taxing consumption to subsidize production, modern-day tariffs would redirect a portion of U.S. demand toward increasing the total amount of goods and services produced at home. That would lead U.S. GDP to rise, resulting in higher employment, higher wages, and less debt. American households would be able to consume more, even as consumption as a share of GDP declined…

Thanks to its relatively open trade account and even more open capital account, the American economy more or less automatically absorbs excess production from trade partners who have implemented beggar-my-neighbor policies. It is the global consumer of last resort. The purpose of tariffs for the United States should be to cancel this role, so that American producers would no longer have to adjust their production according to the needs of foreign producers. For that reason, such tariffs should be simple, transparent, and widely applied (perhaps excluding trade partners that commit to balancing trade domestically). The aim would not be to protect specific manufacturing sectors or national champions but to counter the United States' pro-consumption and antiproduction orientation.

Pettis’ views on trade policy, and his whole way of thinking about international economics, has drawn pushback from some economists. For example, in September 2023, Tyler Cowen questioned the focus on Chinese domestic consumption as a target for Chinese growth policy. As an alternative, he suggested that China should focus on improving certain dysfunctional service sectors like health care, which will increase both consumption and production.

In November, Pettis vented his frustration with the academic economics establishment in an X thread:

If you want to understand the effects of trade intervention, its ok to ask economic historians, but never ask economists. That's because their answer will almost certainly reflect little more than their ideological position…It was direct and indirect tariffs that in 10 years transformed China's EV production from being well behind that of the US and the EU to becoming the largest and most efficient in the world…Tariffs may not be an especially efficient way for industrial policy to force this rebalancing from consumption to production, but it has a long history of doing so, and it is either very ignorant or very dishonest of economists not to recognize the ways in which they work…To oppose all tariffs on principle shows just how ideologically hysterical the discussion of trade is among mainstream economists.

Tyler responded ascerbically:

I am usually loathe to turn [Marginal Revolution] space over to negative attacks on others, but every now and then I feel there is a real contribution to be made. I have been saying for years that Michael Pettis flat out does not understand international economics, and yet somehow he is treated as an authority in the serious financial press. Here is his recent tweet storm. It is wrong.

As you know, any time there’s an economist food fight, especially over macroeconomics, I am here for it! I wish Tyler had elaborated on his criticisms of Pettis’ paradigm, and I also think Pettis is being unfair in his blanket accusations of ideological bias.

But in any case, I think I have four points to make on this topic.

International economics is really, really hard

The first point is that as far as I can tell, nobody really understands international economics. It’s basically macroeconomics on steroids. There are a huge number of factors that make issues of tariffs, trade surpluses, and the effect of trade on consumption vs. investment very complex. Some of these factors are:

There are many countries in the world, not just two. Although we tend to think about bilateral trade deficits, in fact third parties matter a lot, and there are a lot of them. For example, if China’s trade surplus with America goes down, it might be because China is exporting more components to Vietnam for cheap final assembly, to be shipped onward to American consumers.

Business cycles matter a lot. If countries are in a depression-style situation where interest rates are at the zero lower bound (a “liquidity trap”), a number of standard results about the effects of trade policies — and results about how monetary and fiscal policy affect trade — go out the window. Right now, there are signs that China is in that situation, but the rest of the world is not.

Tariffs interact with monetary and fiscal policy. For example, if the U.S. puts tariffs on China, China might try to cancel those tariffs out by printing a bunch of money, which would make the yuan cheaper. These sorts of interaction depend on understanding how monetary and fiscal policy work (which we don’t really), and also on understanding how policymakers in countries around the world make decisions about monetary and fiscal policy (which we definitely don’t understand).

Exactly why international trade happens in the first place isn’t well understood. There’s the classic theory of comparative advantage. There are theories based on capital-intensive countries investing in labor-intensive countries. There’s Krugman’s “New Trade Theory”, which focuses more on differentiation and variety as the motivation for trade. And so on. The most empirically successful models of trade are just very simple equations called gravity models, which are agnostic on why trade happens, and could arise from a variety of different processes. This means we don’t really know the baseline of what trade between the U.S., China, and other countries would look like without Chinese industrial policies or currency market intervention.

There are all kinds of wrinkles and complications that affect trade, called “frictions”. These include things like home bias in both consumption and financial investing, sovereign default, currency market frictions, and so on. Economists argue back and forth about which of these frictions cause the various “puzzles” in international trade — disconnects between theory and evidence — or whether that’s just how trade works in the first place.

Competition (also called “market structure”) can throw a wrench into all of this. Trade is carried out by companies, and whether Chinese companies and American companies end up making profits on their exports and their domestic sales will affect how they behave. Domestic competitive environments and international competitive environments both matter, and neither one is particularly well-understood.

In graduate school, I took a class in international finance. The professor who taught that class was known for using advanced mathematical methods borrowed from engineering to make models in which two different frictions interacted to affect international trade. That was a big improvement over the standard theories that could only handle one friction. But what if you have seven? It’s hopeless.

I think that one reason no one has come up with an alternative to Michael Pettis’ ultra-simple way of analyzing international economics is that anything more complex that that quickly balloons into an absolute nightmare. Making big sweeping assumptions about how tariffs will affect production and consumption isn’t exactly the most rigorous or empirically testable way to think about trade and industrial policy, but if the alternative is a blizzard of unworkable math that probably still makes way too many simplifying assumptions, maybe you just go with the simple thing.

Also, Pettis’ paradigm isn’t that different from some of the heuristic ideas that orthodox economists have used to analyze trade policy. For example, Ben Bernanke’s early-2000s warnings about a global “savings glut” bear more than a little similarity to Pettis’ ideas, and the IMF’s calls for China to “rebalance” its economy toward domestic consumption in the mid-2000s are very similar to Pettis’ prescription.

Which brings me to my second point: Whatever you think of Pettis’ theories, I think he’s probably the single most important and influential international economics theorist in the world today. His framework for understanding China’s economy and China’s trade policy might not please academics, but from what I can tell, it has been implicitly accepted by most private-sector economists and commentators, and many policymakers as well. It’s a poppier version of the old “savings glut” and “rebalancing” ideas, simplified for general consumption.

When I see China’s top economic policymakers use language like this, I’m almost certain they’re reading Pettis:

China’s ruling Communist Party pledged to make boosting consumer spending a greater policy focus, as weak domestic demand threatens the nation’s annual growth target despite an export boom…“The focus of economic policies needs to shift toward benefiting people’s livelihood and promoting spending,” senior leaders agreed at a meeting of the 24-member decision-making body led by President Xi Jinping, the official Xinhua News Agency reported.

Pettis isn’t the only person to talk about China’s low level of consumption as a share of GDP as an important problem, or to advocate “rebalancing”. Nor was he necessarily the first. But he has been the most consistent and relentless, and these days I see him cited very frequently. Put simply, Pettis is winning this debate.

A pretty simple way that Pettis could be (sort of) right

My third point is that I can see a pretty simple way in which an approximation of Pettis’ view might be useful, if not to understand international economics in general, then at least to understand the Second China Shock specifically. Basically, it’s all about the profits of Chinese companies.

So far, China’s main methods of fighting its real-estate-induced recession is to pump up manufacturing production, especially in capital-intensive high-tech industries — machinery, ships, planes, cars, batteries, drones, semiconductors, and so on. The Wire China had a great interview with Barry Naughton (probably the top American expert on China’s industrial policies) in which he explains what Xi Jinping is trying to do:

Of course, we don’t know for sure what goes on in Xi Jinping’s mind. But I think we can characterize his approach as this: ‘Billions for tech, but not one cent for bailouts.’…Xi Jinping doesn’t really care about what Chinese people want to buy and want to make, because that would be just ordinary GDP. He’s asserting that there’s something more fundamental than that: high quality GDP, which is determined, at the end of the day, by Xi Jinping himself…

[This] leads to a massive misallocation of resources, so that the underlying productivity of the economy is basically not improving. When we look at total factor productivity growth…China’s not really experiencing significant productivity growth. That is astonishing, because if we look at this economy that’s implementing all these new technologies, we think, wow, that’s gotta produce some kind of explosive growth in productivity. But we don’t see it…

And it’s fundamentally because, for example, China is investing in lots of semiconductor equipment plants that are losing immense amounts of money; it’s investing in thousands of miles of high speed rail that go where nobody wants to go.

In other words, Xi is making the Chinese economy look a little bit more like the old Soviet one, where production was determined by plans instead of by the market. He’s using banks and industrial policy to tell Chinese companies to build a bunch of specific high-tech manufactured products, and they’re doing what he’s telling them to.

Why did this approach fail in the USSR? Ultimately, it was because Soviet manufacturers were inefficient — they made a bunch of stuff, but they produced it at a loss. That was unsustainable.

Chinese factories are a lot better than Soviet ones were. But if you tell enough different manufacturers to all produce the same stuff at the same time, they’re going to compete with each other, and their profits will mostly fall, and they’ll start taking big losses.

In fact, we can already see this starting to happen in China:

And here’s the ever-excellent Kyle Chan:

China’s solar manufacturing industry is struggling to stop excessive capacity expansion and a price war. One set of tools Beijing uses to control over-expansion is tighter regulatory requirements on financing, resource use, and tech. But of course the devil is in the enforcement.

You see similar policy efforts across a range of industries facing similar challenges in China: steel, coal, shipbuilding, batteries, wind. Other policy tools range from the curtailment of subsidies to outright moratoriums on new projects or new firms, like China’s temporary moratorium on new shipbuilding firms after the global financial crisis.

Even in China’s vaunted auto industry, profits are collapsing and a shakeout is occurring. The once-legendary auto giant SAIC is flailing.

(Fun historical side note: From the 1950s through the 1980s, a major aspect of Japan’s industrial policy was about trying to prevent the profits of Japanese companies from collapsing via overproduction and over-competition, usually by forming cartels to restrain production in manufacturing industries. In contrast, Xi’s China is just going full speed ahead for yet more production.)

Chinese companies are responding to this in a very natural manner — trying to export their products when they can’t sell them at home. When people talk about “overcapacity”, this is what they’re talking about. Export profits are keeping many Chinese manufacturing companies — and, increasingly, the Chinese economy itself — afloat.

Exporting your way out of a recession is fine and good — it’s basically how Germany and South Korea shrugged off the Great Recession in the early 2010s.3 But China’s export boom is heavily subsidized, both with explicit government subsidies, and — more importantly — with ultra-cheap abundant bank loans. Subsidies are distortionary — they mean that China is making the cars that Germany and Thailand and Indonesia and other countries would be making for themselves if markets were allowed to operate freely. By subsidizing exports on such a massive scale, China is distorting the whole global economy.

But, you may ask, as long as China’s taxpayers (who pay the cost of explicit subsidies) and savers (who pay the cost of underpriced bank loans) are footing the bill, why should people outside China worry about those distortions? Basically, China is paying for Germans and Thai people and Indonesians to have cheap cars instead of having to make the cars themselves. Why should anyone be angry?

Well, three reasons. First of all, if a wave of underpriced Chinese exports forcibly deindustrializes the rest of the world — a possibility I’m sure Xi Jinping has considered — then it could weaken the world’s ability to resist the military power of China and of Chinese proxies like Russia and North Korea. That’s scary.

Second of all, even if a bunch of cheap Chinese stuff looks like a gift in the short term, it can create financial imbalances that cause bubbles and crashes in other countries. This is the “savings glut” hypothesis for why the global economy crashed after the First China Shock in the 2000s.

And third, a flood of cheap Chinese stuff can cause disruptions and chaos in other economies, hurting lots of workers a lot even as it helps most consumers a little.

Michael Pettis also argues that cheap Chinese stuff actually makes Americans poorer, by reducing their domestic production so much that Americans actually end up consuming less. I’m highly skeptical of this argument, since a basic principle of economics is that people don’t voluntarily do things that make them poorer.4 But perhaps military weakness, financial instability, and labor market disruptions are scary enough.

So what should countries do to prevent this? Tariffs are one obvious answer. If the world raises tariffs on China high enough, exchange rates will have difficulty adjusting, and Chinese products will have difficulty penetrating foreign markets. Chinese companies will then have to fall back on their domestic market. This will intensify the effect of competition, and reduce their profits much more quickly.

The sooner Chinese companies’ profits collapse, they will cut back on production. They’ll also probably pressure the government to stop subsidizing overproduction, in order to lessen the competitive effect and keep themselves in the black. This political pressure could be what finally pushes Xi Jinping and the CCP to change China’s economic model, reducing incentives for overproduction.

This would be good for Chinese consumers. They get a temporary flood of cheap goods when Chinese companies flood the domestic market. If and when China’s government reduced the fiscal and financial incentives for overproduction, China’s taxpayers and savers would get a much-needed reprieve. And in the long run, a less distorted Chinese economy would be good for productivity, since resources would be diverted to sectors that have more room for improvement, like health care and other services.

This scenario isn’t exactly what Pettis envisions, but it’s reasonably close. It features tariffs forcing China to rebalance its model from production to consumption, ultimately benefitting regular Chinese people. And it’s pretty easy to understand this scenario in terms of pretty standard orthodox economic concepts — subsidies, distortions, productivity, and competition — plus a little bit of political economy thrown in.

Now, this wouldn’t mean Pettis’ paradigm would be right in general. This scenario would only work because of unique features of Chinese industrial policy and Chinese domestic politics. But since the Second China Shock is one of the most important things happening in the global economy right now, I think there’s a chance that Pettis’ paradigm is making itself useful.

Pettis needs to think harder about the downsides of tariffs

That said, I think it’s also possible that Pettis is overlooking or (more likely) downplaying some major pitfalls of his approach. This is my fourth point.

Pettis assumes that because America runs a big trade deficit, tariffs would pump up U.S. manufacturing so much that not only U.S. GDP, but also U.S. consumption, would end up increasing. He writes:

By taxing consumption to subsidize production, modern-day tariffs would redirect a portion of U.S. demand toward increasing the total amount of goods and services produced at home. That would lead U.S. GDP to rise, resulting in higher employment, higher wages, and less debt. American households would be able to consume more, even as consumption as a share of GDP declined.

But Trump’s tariffs in his first term didn’t do anything of the kind. Industrial production actually declined after Trump put up his tariffs:

There was no surge in factory construction, either; that only happened once Biden came into office and enacted industrial policies (the CHIPS Act and the IRA).

There wasn’t much action in the trade deficit either. If you squint really hard you can see a small improvement right before the pandemic began, but then a total collapse afterward:

What happened? Two things. First, the U.S. dollar appreciated in response to the tariffs, cancelling out at least part of the effect. Second, U.S. manufacturers suffered when they had to pay a lot more for parts and components. These are very general problems with tariffs as a policy, and I discussed both of them in more detail in this post:

Instead of quoting my earlier post, I’ll quote Matthew C. Klein, who co-authored the book Trade Wars are Class Wars with Pettis, and who recently wrote an op-ed explaining how tariffs could easily backfire:

Spending on manufacturing imports tends to track the business cycle and new orders for American-made goods. Imposing “universal” tariffs high enough to force those imports to fall by more than 40 percent to close the trade deficit would likely involve a severe economic downturn that hurts Americans more than anyone else. To avoid that pain, domestic production of those same goods would have to rise enough to cover the gap — and rise fast enough to prevent shortages and inflation. The experience of the pandemic suggests that this is not a realistic option…

Another counterintuitive impact is that the dollar tends to become more expensive in response to the imposition — or threat — of new tariffs…[This] means that goods made in the U.S. become more expensive for customers in the rest of the world. The net effect is that tariffs often hit exports more than imports, even when foreign trade partners fail to retaliate.

Pettis doesn’t really seem to grapple with either point. It’s possible that he believes that Trump’s first-term tariffs were a failure because China simply rerouted its exports through Vietnam; in this case, putting tariffs on all other countries, as Pettis recommends, would close off that loophole. But that still wouldn’t deal with the question of exchange rate appreciation. Unless tariffs on the rest of the world are so huge that they overwhelm the dollar’s ability to adjust to compensate, some sort of financial intervention to keep the dollar weak would be necessary in order to make tariffs effective. Pettis has suggested taxing capital inflows, which could do the trick,5 but this kind of intervention doesn’t seem on the table for the Trump administration.

And Pettis also fails to grapple with the intermediate goods problem. The U.S. would not benefit from going back to the kind of quasi-autarkic economy it was during World War 2 — technology has changed too much for any country to prosper while walling itself off from the rest of the world. The U.S. can onshore and harden its supply chains to some extent, but no matter what, U.S. manufacturers are still going to have to order some materials, parts, and components overseas. I haven’t yet seen Pettis suggest a solution to this problem, or think hard about the failure of Trump’s tariffs to increase industrial production in the U.S. six years ago.

So while I think Pettis’ paradigm probably does a good job grappling with the unique characteristics of the Second China Shock and China’s political economy, I don’t think we should rush to make it our general default paradigm for thinking about trade, tariffs, and international economics in general. It still needs a lot of fleshing out.

Update: Tyler Cowen and Paul Krugman both weigh in on Michael Pettis Thought.

Actually, this is not entirely true. There is an argument that America, because it has the reserve currency, actually does have a comparative advantage in writing IOUs, because those IOUs are used for international payments and risk hedging and stuff like that, and thus represent a form of disguised financial services. But it’s hard to apply this argument to the developing countries that are accounting for more and more of China’s trade surplus. Very few people think Vietnam or Brazil or Saudi Arabia has a comparative advantage in financial services.

I tried to suggest intentional devaluation of the dollar via exchange rate intervention as an alternative, but nobody has been particularly interested in this idea.

Germany may have hurt its European neighbors somewhat by exporting too much to them, since at that point they were all at the zero lower bound.

In order for cheap Chinese imports to actually impoverish Americans, there would have to be some kind of externality or coordination problem involved. That might be the case, but Pettis or the MAGA people need to explain what they think that externality is. It’s not readily apparent to me what it might be.

Though currency market intervention by the Fed would be more effective and much easier to implement!

'Michael Pettis also argues that cheap Chinese stuff actually makes Americans poorer, by reducing their domestic production so much that Americans actually end up consuming less. I’m highly skeptical of this argument, since a basic principle of economics is that people don’t voluntarily do things that make them poorer.'

I am not sure how this principle holds when you take large and heterogeneous groups such as 'Americans' or the 'Chinese' (and even for smaller groups it fails if you'd ask me). There are plenty of Americans who would do something that would make others poorer, as long as it makes them richer, even if total wealth decreases. Pushing addictive painkillers (or illegal drugs) on the market was a voluntary choice of some, even if drug (or painkiller) addictions reduce productivity of the addicted and thus total productivity and wealth creation. Moving production to the other side of the world has certainly made CEO's and shareholders wealthier, but not factory workers, nor plenty of local communities (and who says the shareholders and CEO's are domesticated in the US, meaning that even more corporate profits move elsewhere). The increasing call for onshoring and the potential economic benefits thereof shows that these past actions might have been a voluntary mistake, from a national point of view.

Buying a cheaper Chinese car does seem like an individually rational choice, but when a sufficient number of people makes this choice this could push some other manufacturer over the brink, meaning that an even larger number of cars won't be made in the US. And considering the size of automotive plants and companies these days, the bankruptcy of a company like Ford, however unlikely it seems, would certainly make Americans poorer.

Even on an individual level: How many people have voluntarily bought NFT's?

This doesn't say anything about whether or not we need tariffs though, it's just that your 'basic principle of economics' can work if, and only if, people would be fully 'rational' (which we're not) and have full information of the future effects of their actions (which we don't), and you see a nation as a homogeneous entity (which it is not). So maybe that basic principle needs to be revised if you're trying to make sense of the real world?

This is one of my favourite topics but one I don't fully understand. Here is my understanding and I would love it if you or anyone else could answer some questions that I have:

The Chinese government (especially the CCP) has amassed a great war chest in terms of funds/assets through taxation of individuals and companies which, in turn, received payments from around the world in the first two decades of the 21st century. In essence, 1 out of every 100 dollars or their equivalent created around the world by various central banks probably went into the CCP's pockets. China became the factory of the world as companies increasingly used its massive labour force and pro-capital policies working with thousands of contract manufacturers, especially as the products of Japanese and Korean companies became more expensive and American and European companies outsourced jobs and factories to China to produce goods at scale for an increasingly globalised world.

Given the state-owned banking system and a snakehold over financial executives, the CCP used some of this tax revenue as well as international dollar bonds issued by local governments through local government financing vehicles (LGFVs) to subsidise the manufacturing sector when it could have spent it instead on improving healthcare. (The high taxation levels also probably stopped Chinese workers from building wealth through their incomes so they went on a house buying binge.) Chinese companies, on the other hand, began to become global exporters in their own right developing their own 'brands' targeting the less affluent markets initially and then entering European and American markets. The emergence of the internet and improved shipping networks allowed them to export directly to the end consumer (e.g. Shein) or else export directly to wholesalers/retailers.

The People's Bank of China also controls the exchange rate preventing it from appreciating as renmimbi increasingly became an important currency in international trade.

So my questions are:

1) Why don't other large developing countries (India, Brazil, Indonesia) copy this?

2) If you think of the CCP or the Chinese government as basically a big bank that makes sub-optimal lending decisions then won't the money run out sometime? When?

3) China needs to increase domestic demand or consumption but what does that mean in practice? What are they unable to do that people take for granted in developed countries? Is this just a roundabout way of saying the CCP or the Chinese government needs to tax less and banks need to reduce interest rates for personal loans or credit card loans or give out more loans than they currently do etc.

4) Much of China's trade with the world actually involves intermediate goods, not final goods. Given companies rarely like to change suppliers and it's hard to find ones that can produce at scale, speed and at cost then can there ever truly be any alternatives?

5) Wouldn't the world suffer if tariffs on Chinese intermediate goods leads to higher prices for consumers worldwide? Doesn't everyone deserve an Alexa or an iPhone or their knock-offs?

6) If the PBOC controls the exchange rate like this and it has largely worked out for them then why do we advocate free float of exchange rates for developing countries? Provided they're good at managing their reserves, shouldn't they pick an optimal exchange rate and stick to it? How is it that some countries like Japan and China can control exchange rates but others like Sri Lanka or Argentina or Indonesia or India can't?