Macroeconomics: The predator of foolish regimes

One thing no ruler can control.

Bolivia isn’t a country we talk about a lot. It’s a small landlocked South American nation of 12 million people whose economy is dependent on mining and natural gas. Back in 2006, Bolivia elected a socialist leader, Evo Morales. You might assume that Bolivia’s economy would follow the disastrous example of Hugo Chavez’s Venezuela, with which it was closely aligned. But in fact, it didn’t. The Bolivian economy did fine under Morales. Growth was robust, and poverty and inequality declined. I wrote about Bolivia’s apparent socialist success for Bloomberg back in 2019:

By 2017, Bolivia was 42 percent richer than when Morales took office. But for the average Bolivian, the results were even better -- the country’s Gini coefficient, a measure of income inequality, fell by more than 19 percent since Morales took office. Poverty has declined by 25 percent since he was elected. Although Morales has showed some disturbingly authoritarian tendencies, including doing away with presidential term limits, economically he seems to have turned his country around.

But I noted that underneath the surface, trouble was brewing. Drawing on some 2019 research by Kehoe et al., I pointed out that Bolivia’s currency peg and dwindling foreign exchange reserves put it in danger of a classic emerging-market currency crisis:

When there is pressure for the dollar to strengthen -- and thus for the domestic currency to weaken -- the government has to sell dollar-denominated assets…If Bolivia ever runs out of [reserves of] dollar assets, it won’t be able to stop the boliviano from depreciating, resulting in a very rapid crash in the currency’s value…Reserves have now fallen to about half of their peak levels…

A currency plunge is an especially frightening prospect because of Bolivia’s increasing external debt…[T]he amount that Bolivia’s government owes in foreign currencies has approximately quintupled since 2007…If Bolivia is ever forced to abandon the dollar peg and the boliviano drops in value, this foreign-currency debt could become very costly to service. Bolivia could then be forced to choose between two disastrous alternatives -- a sovereign default, or Venezuela-style hyperinflation.

In other words, Bolivia was making the same classic mistakes that resource-dependent countries so often make — trying to keep their people happy by keeping their currency too strong, in order to make imports cheap, setting themselves up for a macroeconomic disaster.

Here’s a brief refresher on how this all works. Regular people in countries like Bolivia depend on imported food and fuel for their daily lives. To import food and fuel you need dollars — or some other international currency like euros or yen or yuan or whatever. Bolivia can get dollars two ways — by selling exports or by selling bonds. If it doesn’t sell enough exports — for example, if gas prices drop and its exports are worth less — it has to sell bonds in order to keep importing.

The country maintains a stockpile of “reserves” — basically, bonds that pay off in dollars — that it can use to buy imports if export revenue temporarily goes down. But if the country tries to maintain an exchange rate peg — basically, declaring that its currency is worth more dollars than it’s really worth, so it can keep buying more imports than it can really afford — then the stockpile of reserves will eventually get used up. At that point there’s no way to stop the country’s currency from crashing in value relative to the dollar, as everyone desperately exchanges more and more of their local currency for dollars in order to keep buying imported food and fuel. This abruptly impoverishes the citizenry, and it tends to lead to either a sovereign default or hyperinflation (for reasons you can read about in my post about Sri Lanka’s crisis back in 2022).

So basically, I predicted that Bolivia’s economy was in danger not from socialism — which seemed to be implemented far more prudently than in Venezuela — but from macroeconomic mistakes. Socialist or not, Bolivia was in danger of the kind of standard, well-known economic crisis that resource-exporting countries tend to stumble into.

Well, fast forward to 2024, and the dangers I warned about have now come to pass.1 Juan Pablo Spinetto tells the tale:

[Bolivia is having] a financial meltdown: an old-fashioned balance of payment crisis triggered by the lack of international reserves to defend an exchange rate fixed to the US dollar since 2011. With international reserves at about a tenth of their $15 billion peak in 2014, the government of President Luis Arce is safekeeping every dollar bill and gram of gold, depressing activity, sparking fuel shortages and stoking social unrest — all in the name of avoiding a devaluation of an untenable 6.9 boliviano-per-dollar peg…

Annual inflation spiked to almost 8% in October, the highest since the implementation of the peg. The lack of dollars led to parallel exchange rates, feverish currency speculation and suppliers demanding payments in hard currency, amounting to the informal dollarization of the economy.

As Spinetto notes, the country’s forex reserves are almost entirely gone now, which is why the crisis came when it did:

There is one difference. I predicted that a currency crisis might be sparked by a drop in the price of natural gas. Instead, what precipitated Bolivia’s slide into crisis appears to have been a drop in natural gas production, along with government policies that spent foreign exchange reserves on imports. Peter Millard and Sergio Mendoza write:

A lack of investment and exploration of gas fields ultimately tanked production, resulting in today’s nationwide diesel shortage…What’s more, fuel subsidies — which make gasoline even cheaper than in Saudi Arabia — have drained foreign reserves…

When Morales overhauled the natural gas industry in 2006, he raised taxes so much that oil majors…simply produced from the wells they had already drilled instead of spending to increase output at existing fields or trying to find others…The government was also using overly optimistic calculations of how much gas it had already discovered and gave little thought to the necessary investments to keep output stable for the coming decades.

So you actually can see some similarities with Venezuela’s downfall here. In both countries, a long-term lack of investment in the main export industry (oil for Venezuela, gas for Bolivia) led to a lack of exports and a shortage of incoming dollars, eventually causing a currency crisis. Both countries lived for the moment, offering their people more government largesse and more cheap imports than they could afford in the long term, and setting themselves up for disaster when the music stopped. In Bolivia’s case I’d call it populism rather than socialism, but that’s splitting hairs.

But the main point here is that bad macroeconomic management spells doom for a ruling regime, whether it’s “socialist”, “capitalist”, or something else. If you maintain an exchange rate peg to support unsustainable levels of imports, you will have a crash. If you take out a ton of loans denominated in foreign currency, a crash will cause you to either default or suffer hyperinflation. No matter how you set up the distribution of power and wealth inside your country, you will have to deal with those macroeconomic laws.

As it turns out, this sort of emerging-market crisis isn’t the only kind of macroeconomic crisis a country can have. There’s another common type: the deflationary depression. That’s the kind of crisis America got itself into in the 1930s and the late 2000s, and Japan got itself into in the 1990s.

This sort of crisis is marked not by inflation, but by disinflation2 or deflation. The causes of these are not as well-understood as the emerging-market currency crisis,3 but the triggering event is usually a financial bubble and crash accompanied by a large amount of private-sector debt. The typical result is years of slow growth and high unemployment, accompanied by low or even negative inflation rates. If you’re an American who’s old enough to remember the period from 2008 to 2012, you’ve experienced one of these.

One of the big problems in this sort of crisis is “debt deflation”. This isn’t actually a type of deflation — it’s the name for the vicious cycle of reinforcement between debt and deflation in a depression-style episode. Basically, deflation exacerbates debt.

In general, interest payments and principal payments on loans and bonds are not adjusted for inflation — if you owe $1000, and suddenly there’s deflation so $1000 is worth a lot more, then you suddenly owe a lot more in real terms (i.e., you owe a lot more relative to your income). When people suddenly owe a lot more, they either A) cut back on consumption, or B) default on their debt. Either of these things reduces aggregate demand — either people buy less stuff in order to pay down their debts, or a wave of defaults hurts the already-wounded banking system. Lower aggregate demand makes deflation worse. And so the vicious cycle continues.

China is experiencing this sort of problem right now, following the burst of its real estate bubble back in 2021-23. Lingling Wei reports:

Over the past week…China’s 10-year sovereign yield kept falling to fresh lows. Now, the yield is around 1.7%, a full percentage-point plunge from a little over a year ago. The return on the 30-year government bond has also dropped below 2%…The sovereign-debt yield still has a ways to go before falling to zero, but the speed of the drop is astonishing. The lower the yield falls, the deeper the market is signaling economic stress…Official statistics show that China’s economy grew at 4.6% in the third quarter and is expected to reach the 5%-or-so target for the full year. In reality, businesses are struggling to keep their lights on, people are having severe difficulty in finding jobs, and municipalities are drowning in debt. Even government employees aren’t getting paid.

“It feels like depression,” a reader in China recently wrote to me.

Note that there are signs that China’s official 4.6% growth rate is still being substantially overstated.

And here’s Hannah Miao of the WSJ on China’s deflation problem:

Prices for goods leaving Chinese factories have fallen year-over-year for 26 consecutive months, dropping 2.5% in November from a year earlier, and there is little sign of them turning up again soon. China’s gross domestic product deflator, a broader gauge of price levels across the economy, has been in negative territory for six consecutive quarters, the longest stretch since the late 1990s…The fear is that deflation is becoming ingrained in China. As falling prices sap profitability, companies could postpone investments or shed workers, leading more people to cut back on spending. Others might put off purchases because they think prices will drop even more.

Here’s a pretty striking chart:

Note that China’s strategy of producing vast amount of industrial goods could easily exacerbate deflation, by causing a glut of overcapacity that forces prices down. Profits are falling at Chinese companies, because the government is pushing companies all over the country to make too much product. This is almost certainly contributing to falling producer prices. If the U.S. and other countries raise tariffs on Chinese goods, it could send Chinese products back to China and make the deflation there even worse.

The generally accepted way a country gets out of debt deflation is to stimulate aggregate demand, with monetary easing and fiscal stimulus.4 This is why everyone is calling on China’s government to unleash massive stimulus. Xi Jinping was very reluctant to do this at first, being a generally conservative sort of guy. Now he’s ramping up stimulus at last, but as Wei reports, the bond markets don’t seem to be encouraged just yet.

Note that the policy responses to the two common types of crises are in some ways exact opposites. In an emerging-market currency crisis you generally want to cut government debt, in order to stabilize the currency. But in a deflationary depression, you want to increase government debt, in order to stimulate aggregate demand. Getting the policy right requires knowing which kind of crisis you’re in. (In 2009-11, some economists who are used to studying emerging-market crises suggested cutting government deficits, but this would have been the wrong medicine.)

In any case, we see that macroeconomics is like a predator that eats foolish regimes, both democratic and authoritarian. Countries that ignore time-honored principles like “Don’t try to keep your currency overvalued with a dollar peg”, “Don’t borrow a ton of money in foreign currency”, or “Don’t respond to deflation with fiscal austerity” are just asking for trouble.

Authoritarian regimes often think they can control the macroeconomy by controlling the microeconomy. Venezuela tried to stop inflation with price controls, and ended up just making the problem worse. Xi Jinping is trying to escape deflation by engineering a massive glut of manufactured products, which is likely making his problems worse. Macro problems have to be solved with macro solutions — austerity for inflation, stimulus for deflation, and so on.

Leader who think they can order around the vast, imponderable forces of macroeconomics the way they order around their domestic constituencies are generally in for a rude awakening.

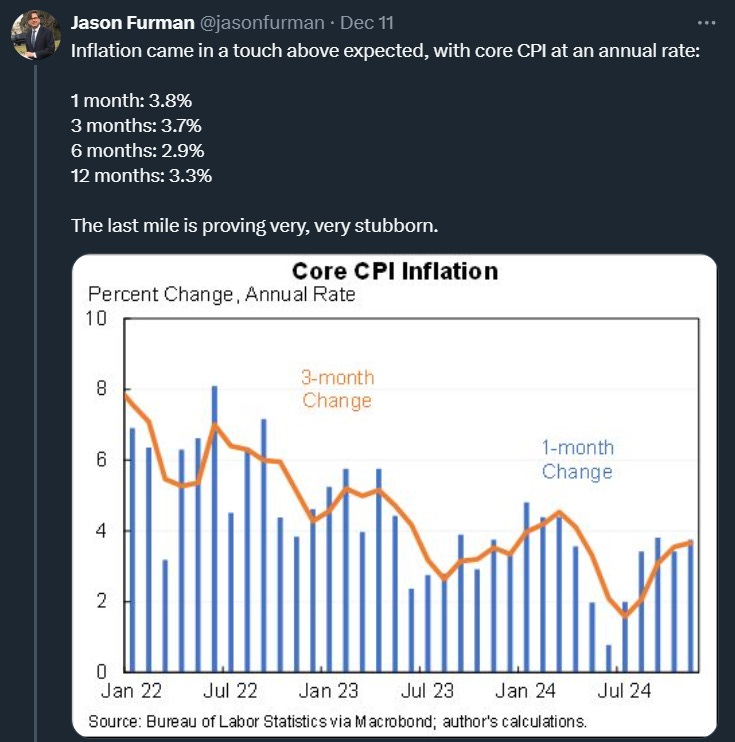

I would like you to think about this in the context of the United States’ current incoming government. Inflationary pressures have waned somewhat in the U.S. thanks to the rate hikes, but they still exist:

In a pre-election post, I suggested that Trump forcing the Fed to keep rates low, while vastly increasing the deficit with tax cuts, constituted a big inflationary risk. But I also think we should consider the implications of MAGA influencers like Elon Musk sabotaging efforts to keep the government running:

It’s not clear whether on balance these sorts of shenanigans will be deflationary or inflationary. If repeated and intensified over time, these pressure campaigns could cause a crisis of confidence in U.S. economic policy, sparking capital outflows, putting downward pressure on the dollar, and raising the rate of inflation. On the other hand, suddenly no longer paying a ton of government employees (including the U.S. Military!) would be deflationary, since it would reduce consumption and therefore reduce aggregate demand.

So while I don’t know exactly whether our new GOP government is headed toward massive stimulus or punishing austerity, I think there’s a possibility that this new Trump administration could cause some unforced errors and increased economic difficulty. As I like to say, macro will not be mocked.

I don’t really deserve the credit here, since Kehoe et al. (2019) did the research.

Disinflation is when inflation goes down but still stays positive. Deflation is when inflation actually goes negative.

In brief, the leading theories are A) weakness in the financial system caused by a buildup of bad debts at banks, B) a crisis of consumer confidence (“animal spirits”), and C) a change in consumer behavior toward paying down debt (“balance sheet recession”). These three theories could all be true at once. Debt deflation aggravates (A), (C), and possibly (B) as well.

Some people ask: “How do you solve a debt problem with more debt?”. The answer is: When you shift debt from banks and consumers to the government, you increase bank lending and consumer confidence. Government debt has its own problems — in the long run it fuels inflation. But if you’re in a deflationary depression, fueling inflation probably shouldn’t be your immediate concern. This is why basic Keynesian economics recommends raising government deficits in severe downturns, but counteracting this by enacting austerity when times are good. Often, people who style themselves as “post-Keynesians” forget the second part of this formula.

Great article Noah! Amazing job explaining the difference between currency crises and debt-deflationary depressions.

In countries like Venezuela and Bolivia, they have economists that understand these issues, but rigid political systems prevent reforms. Sometimes, devoping country leaders often prefer blame external actors rather than enact necessary changes. This is worsened by a public that lacks macroeconomic understanding and is content with an artificially inflated standard of living built on draining foreign reserves or increasing dollar denominated debt.

As you highlighted with Bolivia, bad macro economic policies often lead to balance of payments crises. The result would be turning to the IMF.

Unfortunately, many in the developing world mistakenly believe the IMF causes these crises. While IMF policy prescriptions can sometimes create new challenges, the real issue often lies in bad policies the government does to make them borrow from the IMF in the first place (currency anchor, draining foreign reserves, lack of investment, declining exports, and foreign currency borrowing as you described). Then the leaders fail to take responsibility for their policies—like in my country Ghana, which has borrowed from the IMF over 17 times, yet continues to blame the institution rather than addressing systemic issues.

I also wrote about misconceptions of the IMF if anyone wants to read here. I take the same framework Noah Smith uses instead of conspiratorialism:

https://open.substack.com/pub/yawboadu/p/the-imf-part-2-how-the-fund-actually?r=garki&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=true

I think you just explained that macroeconomics is... gravity.