How to devalue the dollar

Trump and Lighthizer want to "weaken" the dollar. It's an idea worth considering, but the devil is in the details.

The other day I was chatting with a politician (who shall remain nameless), and he was telling me how worried he was about China. We talked about the risk of war, and about manufacturing jobs lost to Chinese competition. But then he said something unexpected. “I think their ultimate goal,” he muttered darkly, “is to bring down the dollar.”

I’ll talk about that idea in a bit, but what really struck me was just how reflexively many Americans associate the strength of their currency with the strength of their nation. I’m not really sure why. It might be just an unfortunate misunderstanding of the word “strength”. In fact, dollar “strength” is just a colloquial term — what it means is that the dollar is expensive relative to other currencies. Alternatively, people might realize that the dollar tends to be strong when the U.S. economy is doing well, and assume correlation equals causation. Or maybe Americans are just proud of how many people around the world want to hold their currency.

Whatever the reason, I know two people who don’t think a “strong” dollar is a good idea: Donald Trump and his main trade adviser, Robert Lighthizer. Trump is promising to weaken the dollar if he gets back into office, and Lighthizer appears to be the one who came up with the idea:

Lighthizer himself has been counseling Trump to devalue the strong U.S. dollar if he is elected in order to boost U.S. exports—advice that has been widely read as an audition for the Treasury post…

[Lighthizer] would make it a goal of U.S. policy to balance trade with the rest of the world, not just China. The implications are enormous. One tool, which Lighthizer has reportedly proposed to Trump, is a concerted effort to weaken the U.S. dollar against other currencies. Other things being equal, a cheaper dollar would reduce the prices that foreigners pay for U.S. exports, make imports more expensive for Americans, and help bring trade closer to balance. The dollar, however, has long been overvalued, partly because of its role as the global currency of choice; more recently, it has been soaring in response to a strong U.S. economy and conflicts in the Middle East and Europe that have sent investors running for the safe haven of U.S. assets. Details are scant, but Lighthizer appears to be envisioning a reprise of actions taken by U.S. President Richard Nixon in 1971 and Ronald Reagan in 1987: imposing or threatening tariffs on trading partners unless they agree to take steps to revalue their currencies against the dollar.

This would be a huge change to the global financial system — and to the U.S. economy. That doesn’t mean it would be a bad change. Lighthizer is right that “weakening” the dollar to some extent would likely make U.S. exports more competitive in world markets, and help rebalance the U.S. economy toward manufacturing and away from finance. And in the long run, it could help stabilize the global financial system.

But there are plenty of dangers involved as well. A cheaper dollar would almost certainly fuel higher inflation. It’s also easy to overshoot — a dollar that was too cheap would make life a lot harder for U.S. manufacturers who need to import components and materials. And most of the methods that the U.S. could use to depreciate the dollar are either of questionable effectiveness or would risk big problems in the financial system.

In any case, this is Trump’s biggest and most important economic proposal — bigger than tariffs by far. So I thought I should write an explainer about this whole issue — why the dollar is “strong” in the first place, the costs and benefits of a “strong” dollar, how the dollar might be depreciated, and what this would mean for Americans and for the world.

The basics: Why the dollar is “strong”, and what that means for Americans

The key to understanding international economics is to understand this one simple fact: If you want to buy something a country produces, you need that country’s currency.

Think about this for a second. Suppose I have a business in Japan that makes zippers. Why am I selling zippers? To make money so I can buy stuff. But to me, “money” means “yen”, and the stuff I want to buy — ramen, rent for my Tokyo apartment, day care for my kids, etc. — is priced in yen. So if you want to buy my zippers, whether you’re in Tokyo, Mumbai, or in Wichita, Kansas, you need some yen.

But if you’re in Mumbai or Wichita, you don’t have a bunch of yen just lying around. You need to go get some. So you go to a foreign exchange market, and you swap your rupees or your dollars for yen.

The yen’s value, in terms of rupees or dollars, will be determined by how many people do this, and how many rupees or dollars they swap for yen. In other words, the value of the yen is determined by supply and demand. Every time someone swaps their dollars for yen to buy a Japanese-made zipper, the demand for yen goes up a little bit, and the yen gets a little bit more expensive — i.e., “stronger” — as a result.

Now, I used zippers as an example, but goods and services aren’t the only things you can buy from a foreign country. You can also buy financial assets — bonds, stocks, real estate, and so on. If the Japanese zipper company issues a bond denominated in yen, and you want to buy it, you’re going to need yen in order to buy that bond. So demand for financial assets can also create demand for a currency, and make it more expensive (“stronger”).

Now here’s the thing — when a country’s exchange rate gets “stronger”, it makes that country’s exports more expensive to buy. If there’s a huge demand for a country’s bonds, that will make its currency more expensive. And because its currency is more expensive, it will find it harder to export goods and services.

This is the most common explanation for why the U.S. runs a large trade deficit — somewhere around 3% of GDP1:

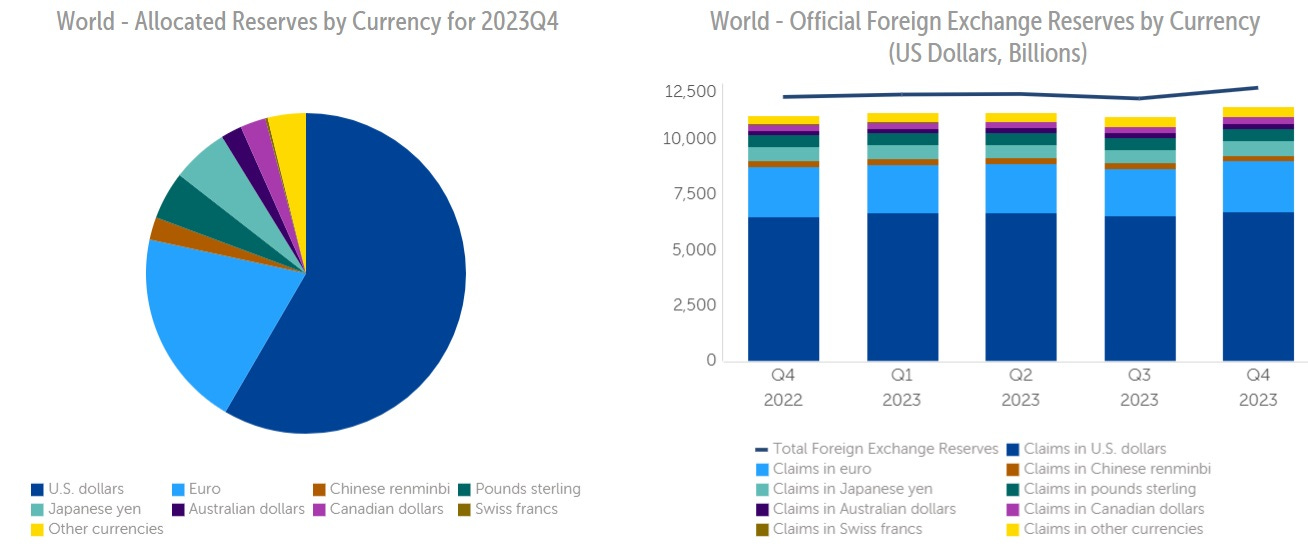

The U.S. dollar functions as the world’s most important reserve currency. That means that a whole bunch of countries around the world hold a whole bunch of U.S. bonds — mostly through their central banks. The foreign-currency bonds held by central banks are called “foreign exchange reserves”, “forex reserves”, or just “reserves”. When we say that most “reserves” around the world are “in dollars”, or that the dollar is “the reserve currency”, what we mean is that most of the foreign-currency bonds that central banks hold are U.S. bonds. In this case, “most” actually means around 60%:

So there’s a lot of demand out there in the world for U.S. bonds. But to buy those bonds, the countries that bought the reserves had to swap their own currencies for dollars. That made the dollar more expensive and the other countries’ currencies cheaper. And that made those countries’ exports of goods and services more competitive, and U.S. exports less competitive. In other words, demand for U.S. bonds crowded out demand for U.S. goods and services.

This makes life harder for U.S. manufacturers and providers of tradable services, because it makes them less competitive. It makes cheap imports — especially cheap Chinese imports — even cheaper, which makes it very hard to keep factories in the U.S. And the resulting decline of U.S. manufacturing weakened our military’s ability to produce a bunch of weapons in case of a major war.

But at the same time, the “strong” dollar makes it easier for Americans to afford cheap imported goods, which lets them consume more. And many economists also believe that it lowers U.S. interest rates, make it easier for Americans to borrow money. Easy borrowing can boost consumption (at least in the short term), and it also gives a boost to the finance industry, which relies on a lot of borrowing in order to operate. Finally, it makes it easier for the U.S. government to levy financial sanctions on other countries, as we did against Russia and Iran.

So there are winners and losers from the “strong” dollar. That’s why I don’t like the word “strong” here — an expensive dollar makes American consumers and financiers and sanctions stronger, but it makes exporters, manufacturers, and the military weaker.

Now, here are two important things we don’t actually know:

We don’t know why all these countries want all these U.S. bonds.

We don’t know how much of the U.S. trade deficit is caused by overseas demand for U.S. bonds.

There are several theories for why countries’ central banks want to hold U.S. bonds, and all of them could potentially be true at once. One theory is that other countries buy U.S. bonds in order to intentionally keep their currencies cheap, so they can export more stuff, because they think exporting more stuff will help their economies in the long run. Another theory is that these U.S. bonds act as a form of insurance against currency crises — if your currency depreciates so much that you have trouble affording imports of food and fuel, you can sell some of your dollar reserves to prop up the value of your currency. A third theory is that because dollars are often used in trade and international finance, other countries want to keep some U.S. bonds around so they can sell them for dollars in order to buy imports. There are some other theories too.

Whatever the reason, it’s likely that the robust international demand for U.S. bonds makes the U.S. dollar more expensive relative to other currencies. How much more expensive, we don’t know. But if you want to reduce the U.S. trade deficit and/or make American exports more competitive on world markets — two different but related goals — then the dollar’s role as the “reserve currency” is one big obstacle standing in your way. As long as a bunch of foreign central banks are out there buying U.S. bonds, the U.S. dollar will always be an expensive currency, making it an uphill battle to sell more American stuff overseas or to even out the balance of trade.

That is why Robert Lighthizer, who cares a whole lot about trade deficits, wants to devalue the U.S. dollar. And that’s also why anyone who cares about preserving and expanding U.S. industrial capacity — which now includes many progressives and many conservatives — will inevitably have to think about the dollar’s value as well.

How would a dollar depreciation work in practice?

If you want your currency to get cheaper, there are a few basic things you can do. These include:

Having the central bank print money (lower interest rates)

Getting Americans to save more

Having the central bank buy foreign currency (currency intervention)

Pressuring foreign countries to appreciate their currencies against the dollar

Putting restrictions on foreigners buying U.S. bonds (capital controls)

Menzie Chinn has a great blog post in which he discusses options (1), (3), and (4) on this list, and includes some useful research papers for reference. Anyway, let’s go through these options and list their strengths and drawbacks.

Printing money / Lower interest rates

First, remember that the value of the dollar in foreign exchange markets is determined by supply and demand for dollars. I’ve talked entirely about the demand side, but the supply side is also important. If you increase the supply of dollars in the world, that should drive the price of dollars (i.e. the exchange rate) down. So the Fed could just print a bunch of money in an attempt to devalue the dollar. This would lower interest rates, which would make buying U.S. bonds a worse deal financially. Presumably, that would get some countries to buy fewer U.S. bonds, thus depreciating the dollar.

There are a couple problems with this. First, printing a bunch of money would cause a bunch of inflation, which Americans are already very mad about. Second, the main trade deficit we care about is the one with China, and the country whose exports we care most about competing with is China. In fact, almost all of the trade imbalance in the world, if you count the EU as one country, is just a U.S. trade deficit matched with a Chinese trade surplus:

China’s central bank probably cares about financial gains and losses a lot less than the central banks of America’s allies in Europe, Asia, etc. So printing money would probably not be as effective in bringing down the U.S.-China trade deficit — it would only affect our much smaller deficits with countries like Korea, Taiwan, and Germany, weakening those allies’ export competitiveness while not doing much to China.

So causing inflation in the U.S. while not doing much to change the U.S./China trade balance doesn’t sound like a great idea. Unsurprisingly, I don’t see anyone suggesting this.

Getting Americans to save more

A second idea — which Chinn doesn’t mention, but which Miles Kimball, who taught me about 2/3 of what you’re reading in this blog post, thought we should do — is to get Americans to save more money. If American households and American companies bought more U.S. bonds, that would make them more expensive (i.e. it will lower interest rates). And it would do so in a way that doesn’t cause inflation, because when Americans save more, it means they consume less, so aggregate demand would fall.

Currently, the U.S. doesn’t save much compared to a lot of other countries, especially China. We might be able to use policy to boost that amount. The question is “How?”. For many years, economists believed that policies like capital gains tax cuts and tax credits for 401k’s and other things like that would get Americans to save more. But if they did, it sure didn’t show up in the aggregate statistics. Personal savings rates have gone mostly down over the years:

Corporate savings rates haven’t really changed much either. So it’s just not clear how to get the U.S. to save more money. One option is deep fiscal austerity, but that’s politically tough, especially at the scale you’d have to do it in order to affect the exchange rate.

And on top of all that, saving more, like printing money, would only reduce our deficit with China if China’s central bank cared a lot about the interest rate it’s getting on U.S. bonds. It probably does not care a lot. So savings inducement is probably a very costly policy for not a lot of gain in terms of exchange rate changes.

Sterilized currency intervention

A third alternative is to have the Fed print money and use it to buy Chinese assets — yuan-denominated bonds, Chinese stocks, real estate, etc. That’s called currency intervention, or forex intervention. It’s what China does to us — it’s how they accumulated all those dollar reserves in the first place. We could just do it right back to them.

If the Fed just did this without doing anything else, it would reduce interest rates and cause a big increase in the supply of dollars, which would raise the risk of inflation, as I mentioned above. That’s called “unsterilized intervention”. But if the Fed bought Chinese assets while also selling U.S. bonds at the same time, the effects on inflation and interest rates would cancel out. That’s called “sterilized intervention”.

Menzie Chinn writes that “there’s not much evidence that for countries with open capital markets this works, on an extended basis,” and sends us to a literature survey by Popper (2022). But Popper doesn’t really conclude much either way — getting convincing empirical evidence for macro stuff like this is inherently hard, because there’s no real way to isolate causality. So I don’t think we really know if this would work, and there’s some theory indicating it might. But the unknowns are large.

In any case, I think sterilized intervention is by far the most promising policy tool in the list, and it’s the one we should be looking at. It would require some legal changes, both to allow the Fed to do it, and to mandate that it do it. But the low risk of inflation, and the fact that we could target the policy specifically to China, make it a pretty attractive option.

Pressuring other countries to devalue their currencies

But anyway, let’s move on and talk about what Robert Lighthizer actually seems to have in mind — pressuring foreign governments to devalue their currencies. Basically, this means we would sit down in a room with the other countries and say “OK guys, you need to stop buying so many U.S. bonds. In fact, sell off the ones you have, until your currency gets more expensive relative to the dollar.”

In fact, we’ve done this once before, in 1985. It was called the Plaza Accord. We successfully pressured European allies and Japan into appreciating their currencies relative to the dollar, and the dollar did in fact get “weaker”. And although people debate how effective it was, the general consensus is that the Plaza Accord largely succeeded in reducing the small U.S. trade deficit of the 1980s.2

So this would actually be a very promising avenue for devaluing the dollar safely, if not for one big problem: The only trading partner that really matters, i.e. China, is not going to do agree to this like America’s allies did in 1985.

Chinese leaders reportedly believe that the Plaza Accord was what derailed Japan’s economy and caused its decades of stagnation. That is probably false — in fact, the Plaza Accord completely failed to reduce America’s bilateral trade deficit with Japan. All of the trade deficit reduction came from Europe. But China’s leaders appear to believe that a big trade surplus is in their national interest, and that appreciating their currency would represent knuckling under to U.S. pressure, and so they’re just not going to do it.

Which means that a “Plaza Accord 2.0”, as Lighthizer seems to be planning, would be aimed entirely at America’s Asian and European allies — whose trade surpluses with the U.S. are very small. If Japan, Taiwan, Korea, etc. appreciated their currencies and China didn’t, it would simply hurt America’s allies and strengthen China. This might count as a “win” in Robert Lighthizer’s mind, but in reality it would be a loss for the U.S.

Capital controls

There’s one more option I could mention, even though it’s incredibly unlikely to happen. Everything I’ve talked about so far is true in a world of free capital movement — in other words, it assumes there’s a “foreign exchange market” where you can just swap dollars for yen, yen for rupees, rupees for euros, and so on. But some countries restrict their citizens and their companies from buying and selling foreign currencies. These restrictions are called “capital controls”. China has capital controls, but currently the U.S. does not.

The U.S could enact capital controls, ending the system of floating exchange rates and more-or-less free capital movement that has prevailed since 1973. We could enact a law restricting foreign purchases of U.S. bonds, or putting a tax on those purchases. The only person I’ve seen suggest this is Michael Pettis:

[A] more direct and focused alternative to tariffs is capital controls. If the United States were to tax capital inflows, or otherwise restrict capital inflows from surplus economies, then there would be no need for the U.S. trade account and its domestic savings rates to adjust to net foreign inflows. There would also be no need for import tariffs.

This would work, though it would take lots of time and effort to implement. And it would cause a wrenching change to our entire economic and financial system.

And in the end, there’s no guarantee that it would reduce our bilateral trade deficit with China — the entire brunt of the adjustment might fall on U.S. allies, who might be forced to run trade deficits against the U.S. in order to balance out China’s trade surplus. This is especially likely because China’s government would be by far the most willing — and able — to pay the tax for buying U.S. bonds. So it would likely keep buying bonds, while other countries would be forced to stop.

If reducing the U.S.’ overall trade deficit is your overriding goal, that counts as a “win”. But if your goal is to strengthen the export industries of the U.S.-led geopolitical bloc relative to China, that would not be a good outcome.

General costs and risks of dollar devaluation

So of all the options on the table, sterilized intervention — having the Fed buy Chinese assets and sell U.S. bonds — seems like the best. Unfortunately, no one is talking about it. And all the other options seem much more likely to punch down on America’s allies, whose economies are already much weaker than our own, while doing relatively little to address the central problem of the bilateral deficit with China.

Also, it’s worth mentioning that any policy to devalue the dollar would inevitably come with some costs and risks. For one thing, dollar devaluation would make imports more expensive for Americans. Another way of putting this is that the U.S.’ trade deficit allows it to increase consumption — not by a huge amount, maybe only 4%, but enough to notice.

More importantly, dollar devaluation could put a lot of strain on the American financial system. It’s not just foreign governments who hold U.S. bonds — in fact, most of those bonds are held domestically, especially by U.S. banks. Devaluing the dollar would lead to lower demand for U.S. bonds, which could drop their price by a little or a lot. This might not be a big danger — in 2015, China sold off a substantial portion of its dollar reserves, and the value of U.S. bonds didn’t really shift (in econ jargon, total demand turned out to be highly inelastic). But if this time turned out differently, it could hurt the balance sheets of many U.S. banks — recall that a decrease in the value of government bonds almost caused a banking crisis back in 2023.

These costs and risks are why, frankly, I don’t expect Trump to actually implement any of Lighthizer’s proposals. Trump would be afraid that anything that caused inflation would lose him popular support. And because he built his own fortune on cheap loans, he’s unlikely to embrace any policy that would cut off major sources of cheap loans from abroad. Also, the TikTok affair showed that Trump is easily pressured by China and its proxies.

But if Biden wins, or if someone else serious gets into office, I would take a look at sterilized currency intervention as a way to nudge China toward appreciating its currency.

And who knows? A nudge might be all it takes. My analysis above was predicated on the idea that China’s leaders don’t want to appreciate the yuan. China’s leaders basically don’t do anything they don’t want to do. But they might change their mind about what’s in their own best interests.

In fact, their mind might already be in the process of changing. The U.S. financial sanctions on Russia have motivated China to start using more yuan in its foreign trade and fewer dollars, in order to reduce its own vulnerability to a similar attack. That effort is still in its infancy, but if it continues, it’ll reduce Chinese demand for dollars somewhat. Meanwhile, China is buying up massive amounts of gold, signaling its shift away from U.S. bonds as the core of its reserves. It may even be selling down some of its U.S. bond holdings, though it’s hard to tell; it might just be having its state-owned banks buy more to compensate.

But in any case, these are signs that China’s leaders are growing less content with a global financial order in which they depend on the hegemony of the U.S. dollar. A nudge, in terms of a well-timed currency intervention by the U.S. government — or even a few more well-placed financial sanctions on Chinse companies that supply Russia’s war effort — might help accelerate this shift in their thinking.

A portion of this trade deficit is fake, for two reasons. First, U.S. companies pretend that they make their profits overseas, in order to avoid taxes. Second, the trade deficit doesn’t take value-added trade into account — it only measures where things were assembled, not where the value of their components and designs was created. But even netting out those two things, the U.S. trade deficit is still quite large.

In fact, it took until 1987 for the trade deficit to start falling. This is because when a country’s currency gets weaker, it takes years for exports to rise and imports to fall as a result. But what happens immediately is that imports get more expensive, which temporarily raise the trade deficit. These are called the “quantity effect” and the “valuation effect”. Eventually the quantity effect should overwhelm the valuation effect, but it takes time.

Re "saving more". We have another tool you didn't mention. Lift the cap on the income subject to social security taxes and plow that money into bonds. It's hard to induce people to save but the government can make it happen. Would be popular politically too, at least for most of the lower 3/4 of the income distribution and likely some of the rest as well

Always count on Lighthizer to beggar his neighbours. He's a zero-sum guy ever since he melded with Trump.