The decade of the Second China Shock

Brace yourselves.

The 2000s were the decade of the First China Shock. As far as I know, the term “China Shock” was coined by the economists David Autor, David Dorn, and Gordon Hanson in a famous 2016 paper. I’m not exaggerating when I say that if you only know one econ paper from the past decade, that should be the one. It was like a meteor crashing into the econ profession. Prior to Autor et al. (2016), “free trade is good” was the most unshakable consensus in the economics profession; after the paper came out, that consensus was shattered.

What Autor et al. showed was that trade with China devastated large swathes of the American workforce in the 2000s. In previous instances of trade expansion, some manufacturing workers had been displaced by competition with German or Japanese or Indonesian imports, but usually they just got jobs elsewhere in the manufacturing industry. China in the 2000s was completely different. The competition was so swift and sudden, so severe, and so spread out across every conceivable industry that American factory workers were left with nowhere to go. Many transitioned permanently into service-sector jobs that paid much less than they had earned before (think: cashier, fry cook, etc.). Some went on the welfare rolls.

Theoretically, this shouldn’t have caused such an earthquake in the econ field. Economists had always agreed that trade can cause “winners and losers” (a polite euphemism for “the shareholders who ship your job to China become millionaires while you become a burger flipper”). Every model agrees on that1. But until the China Shock of the 2000s, they hadn’t really viscerally believed that the losses could be so dramatic. The election of Trump that same year — which a number of papers connected to trade-related job losses — seemed to clinch it. Free trade isn’t always something to celebrate.

But at least economists could tell themselves that the China Shock was over. Both Autor et al. (2016) and subsequent papers by other researchers found that Chinese import competition stopped increasing around 2010, or even slightly earlier. This lines up very well with what we see when we just look at a graph of total manufacturing employment in the United States (though obviously the Great Recession was a part of the story there as well):

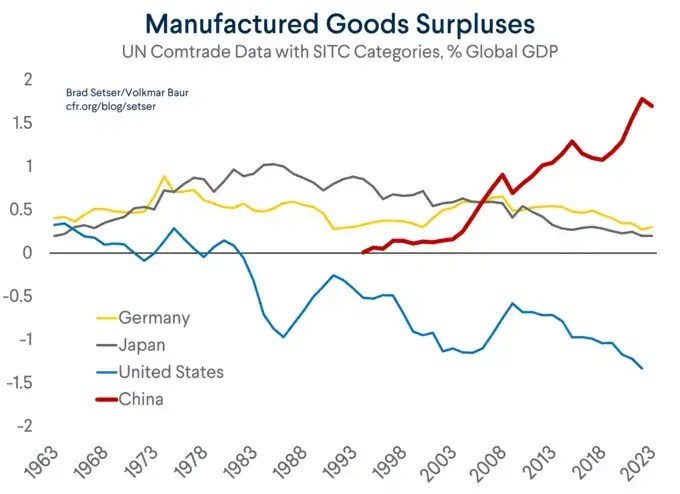

So there was this general sense that this was a one-off — that we rich countries could emerge, battered and bleary-eyed, from the bunkers of the 2010s, and stumble forward with what manufacturing industries remained to us, without the fear that this would happen again. After all, if you look at historical trade competition from Japan, or Germany, or other past competitors, it seems to peak and then level off or decline over time.

Except China, in so many ways, is not like those other competitors. As you can see from the chart above, which is from a recent blog post by Brad Setser and Michael Weilandt, China’s manufacturing surplus — measured relative to the GDP of its trading partners — didn’t stop climbing after 2010. And in the last few years it has been surging again, to heights never dreamed of by Japan or Germany. Meanwhile, headlines are beginning to sound the alarm about a Second China Shock.

This new trade shock will be one of the most important economic stories of the 2020s. So we need to understand it — what it is, why it’s happening, how it’s different from the First China Shock of the 2000s, and what we might want to do about it.

What the Second China Shock is, and why it’s happening

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Noahpinion to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.