Should Democrats go back to neoliberalism?

To some degree, yes. But what they really need is a development state.

Adam Ozimek had an interesting tweet today:

It’s a compelling point. The op-ed he’s referring to is by law professor Zephyr Teachout, in which she accuses grocery stores of using market power to squeeze out smaller competitors and raise prices for consumers. I’m not sure who has “mocked” Teachout’s article, but Alex Tabarrok did a very good job of dismantling its arguments. As Tabarrok points out, Teachout’s argument is simply incoherent; she blames big grocery stores for jacking up the price of eggs, but then she cites lower egg prices at big grocery stores as evidence of this wrongdoing:

Cities have the power to bring down food prices…Big retailers often flex their muscles to demand special deals [from suppliers]…Those discounts are…a major reason that prices are so insane…

Consider eggs. At the independent supermarket near my apartment, the price for a dozen white eggs last week was $5.99. At a major national retailer a few blocks away, it was $3.99…

So the next time you’re staring down a $10 carton of eggs, remember: Call the mayor.

How can big grocery stores raise the price of eggs by charging lower prices for eggs? It seems obviously nonsensical. Teachout argues that big stores use their market power to force suppliers to give them discounts, which in turn forces those suppliers to jack up prices for small stores. She thinks the latter effect outweighs the former — if not for market power, she thinks, eggs would cost $3.99 at the small stores too.

This story requires some pretty heroic assumptions. For Teachout to be right, we have to assume that the suppliers have insufficient market power to resist the big stores, so that they’re forced to offer Costco lower prices. But we also have to assume that the suppliers are able to squeeze the small stores in response, which means we need to assume that the suppliers have some market power of their own — just not as much as the big stores. All of the market power has to work out just right, or the whole story falls apart.

But here’s the thing. We don’t have to just assume all of that stuff; we can easily go check the data. It turns out that even the biggest grocery stores make almost no profit. Costco and Walmart, the biggest and presumably the most powerful grocery stores in the country, both have profit margins of less than 3%, compared to around 12% for the S&P as a whole. Other big stores like Kroger make even less. The big-box grocery stores therefore have very little market power, and are operating at close to cost.

And this makes sense given the fact that the grocery industry is very fragmented — Walmart has a 25% market share nationwide, but everyone else is in the single digits. (And there aren’t even any Walmart stores in NYC!) As Tabarrok notes, the obvious reason the big stores getting better deals from the suppliers is that they’re buying in bulk — which of course is perfectly legal.

Going after grocery stores doesn’t make sense. But Democrats just keep doing it — Elizabeth Warren blamed grocery stores for rising food prices during the post-pandemic inflation, and Joe Biden blamed them later on. Kamala Harris wanted a law against “price gouging” for groceries.

What’s going on? The likeliest answer, I’m guessing, is that Democrats think that by going after grocery stores, they can harness populist rage. The 2010s were a time of popular anger in America, and it felt like whoever could harness and direct that roiling energy would reap political dividends. And since the end of the pandemic, Americans have been mad about inflation. Food is an absolute necessity of life, so higher food prices really hurt the average American. Groceries are something that people buy very frequently, so they tend to notice price changes.

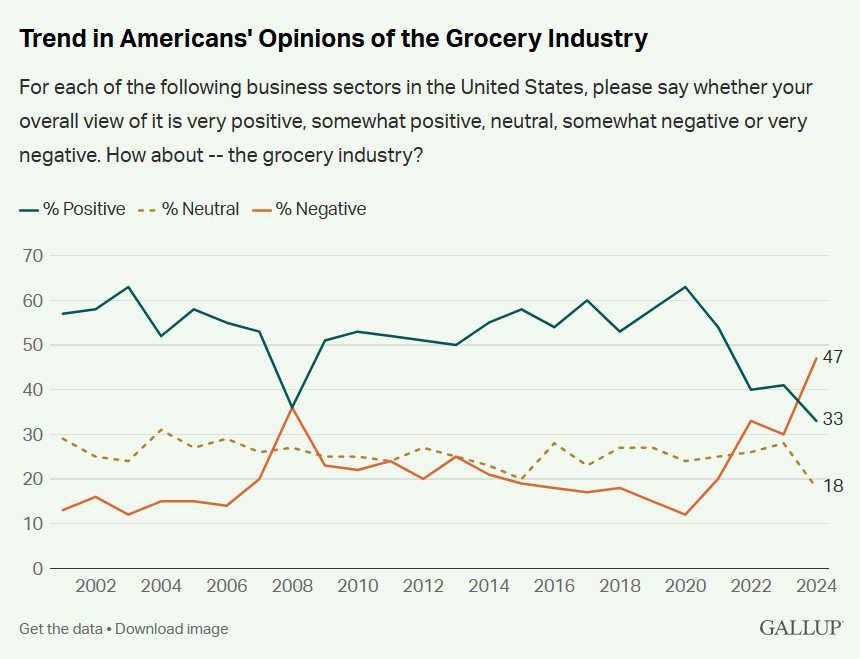

And just like with health insurance, Americans probably tend to get mad at the consumer-facing company who actually charges them money, rather than at the shadowy suppliers who are billing the consumer-facing company — or at external forces like supply shocks. Indeed, grocery stores have become less popular as prices have gone up, even though the stores aren’t profiting much:

So it might make political sense to raise a hue and cry against grocery stores, even if the economics doesn’t make much sense.

But there are at least two big problems with this strategy. First of all, since grocery stores aren’t the actual source of high food prices, coming down hard on them won’t actually help American consumers. Laws against “price gouging” will just force grocery stores to lose money when supply shocks raise their costs. Their thin margins — which don’t actually rise during inflationary episodes — will go negative. They will probably have to close some stores, leaving consumers less well-served, and ironically increasing concentration of the grocery industry at the local level.1

If progressives try to get the government involved in the grocery business, as Zohran Mamdani wants to do, it probably won’t end up going well. In fact, Kansas and other states have experimented with government-owned stores, and they have — pretty predictably — underperformed:

KC Sun Fresh was the city’s attempt to alleviate a lack of access to healthy food in its urban center…But the store, in a city-owned strip mall, is on the verge of closure. Customers say they are increasingly afraid to shop there — even with visible police patrols — because of drug dealing, theft and vagrancy both inside and outside the store and the public library across the street.

KC Sun Fresh lost $885,000 last year and now has only about 4,000 shoppers a week. That’s down from 14,000 a few years ago…Despite a recent $750,000 cash infusion from the city, the shelves are almost bare…

High-profile projects have [also] failed in recent months in Florida and Massachusetts.

As Ezra Klein and the Abundance folks like to point out, at some point you actually have to make stuff work in order to make the voters like you. Getting Americans mad at an undeserving target like grocery stores might win you a couple of elections in the short term, but in the long term, you have to actually address reality; if you fail to bring down food prices, people are going to feel betrayed and get mad at you for failing to keep your promises.

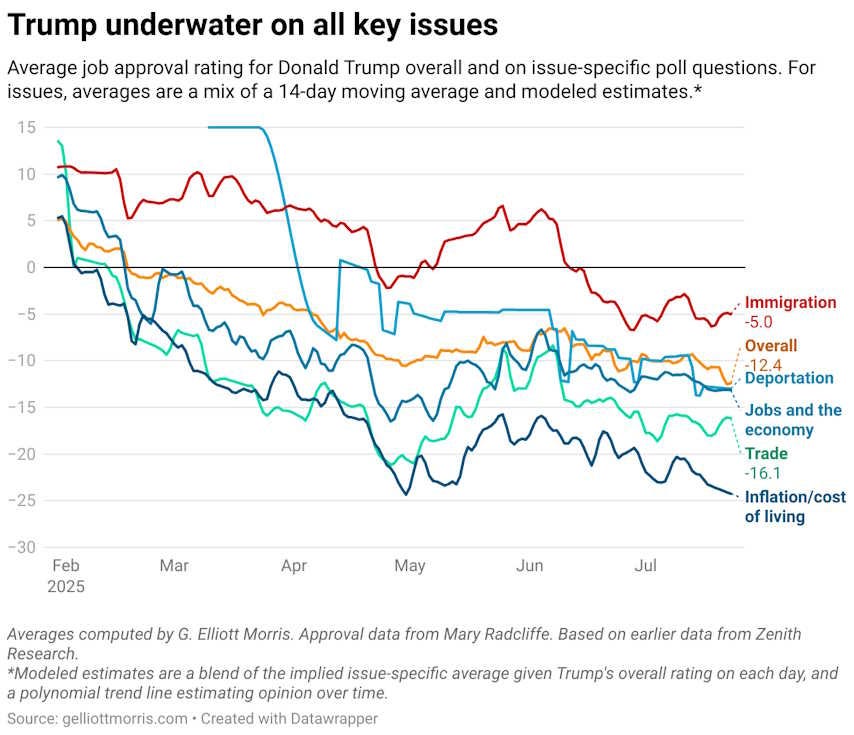

Donald Trump is finding that out now. He campaigned on the idea that kicking out immigrants would bring down prices. Now ICE is rampaging through American communities and rounding people up for “Alligator Alcatraz”, but prices aren’t going down, or even slowing. As a result, inflation has gone from one of Trump’s strongest issues to one of his weakest:

If Democrats blame the cost of living on corporations with 2% profit margins, their attempts to make life in America cheaper will fare no better than Trump’s, and will lead to similar disillusionment.

Meanwhile, there is a well-deserving target that Democrats could attack instead: Trump’s tariffs. Believe it or not, when you tax imported goods, consumer prices go up:

A new analysis from Yale’s Budget Lab, a nonpartisan economic research group, outlines the sweeping effects of 2025’s trade policies…[F]ood prices are expected to rise, with fresh produce alone projected to jump more than 5% as new import taxes ripple through the food system…The report estimates that recent U.S. tariffs — including new taxes on imports from China, Mexico, and Canada — will raise food prices by 2.6% overall in the short run, with sharper increases expected for categories like fruits and vegetables.

There are some signs that this is happening already. Inflation ticked up last month, and imports saw significantly higher price hikes than other goods. Independent investigations have identified a bunch of consumer goods whose prices are probably being pushed up by tariffs.

Trump’s tariffs are an obvious and well-deserving target for Democratic attacks. But because many progressives have decided that “neoliberalism” is the root of all America’s problems, and that attacking neoliberalism is the way forward — and because tariffs are, without a doubt, an anti-neoliberal policy — some progressive Dems have been hesitant to condemn Trump’s tariffs as harshly as they ought to.

It would be pretty ridiculous if Democrats gave a GOP President a pass on policies that actually are driving up the cost of living, in order to try to gin up a populist crusade against grocery stores that are not driving up the cost of living. That would be, in the parlance of internet slang, an epic fail. Fortunately, it looks like Dems are slowly starting to unite around an anti-tariff message.

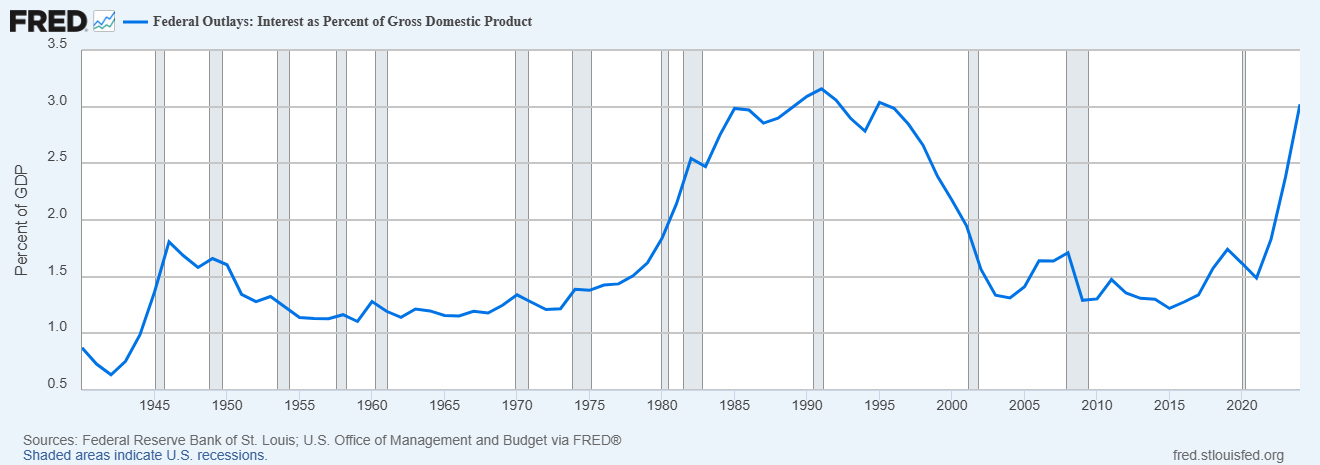

That’s the right thing to do, but it’s going to scare some progressives, because free trade is a pillar of — gasp! — neoliberalism. Nor is it the only area in which a return to the economics of Bill Clinton seems warranted. There’s also the exploding national debt. Trump’s “Big Beautiful Bill”, which will increase deficits by cutting taxes, is highly unpopular with voters. Those new deficits will only add to the problem of rising interest payments that are threatening to swamp the federal budget:

America has too much debt, and it needs austerity — tax increases and spending cuts. Progressive think tanks who pushed the Biden administration to do a bunch of deficit spending in order to stimulate employment are seeing their influence wane, and the radical pro-deficit ideology that calls itself “MMT” has deservedly been disgraced.

And Adam Ozimek is also totally right that in the longer term, deregulation will be an important tool of providing abundance for the people of America. The Abundance agenda isn’t just about deregulation, as its lazier critics allege. But deregulation — especially reforming regulations like NEPA that hold the government back — is definitely an important piece of the equation.

Meanwhile, if we look at what’s happening overseas, market-oriented policy is doing pretty well. Javier Milei’s libertarian program is showing some promising results in Argentina, especially compared to the disastrous Venezuelan socialist regime that some leading American progressives supported. Countries like Poland and Singapore have rocketed up the income charts, thanks mostly to neoliberal policies and foreign investment.

So if Democrats should embrace free trade, austerity, and deregulation, won’t that just make them neoliberals? Well, to some extent, yes. Economic reality — rising interest costs, persistent inflation, the harms from poorly crafted regulation — means that if Democrats want to actually improve the lives of average Americans, they need to return at least partially to the approaches of the Clinton years.

Politically, neoliberalism makes sense too. Trump has seized the banner of anti-neoliberalism for himself, and it’s not going well for him. Simple opposition to Trump’s disastrous ideas will probably earn political dividends for Dems in the short term.

As for progressivism, a neoliberal welfare state centered around things like child tax credits will be a much more effective way of helping the poor and working class than a kludgeocracy of consumer subsidies, rent controls, “everything bagel” contracting requirements, government job provision, share buyback bans, anti-price-gouging laws, and so on. Clinton and Obama made progress toward a simple, effective neoliberal welfare state, with expansions of the EITC and CTC, as well as programs like food stamps. Redistribution isn’t always better than “predistribution”, but in America the former has proven more politically feasible than the latter.

But at the same time, there are important reasons Democrats shouldn’t just copy-paste the Bill Clinton economic approach. For one thing, the country still needs industrial policy if it’s going to stand up to China effectively, both on the economic front, and militarily. Also, a key piece of the Abundance agenda is state capacity — the ability of the government to get things done in-house. The government needs to build infrastructure and energy (and hopefully housing), and continuing to outsource those crucial functions to overpriced consultants and ineffectual nonprofits is not going to cut it. The U.S. needs a bureaucracy big enough and competent enough to be able to carry out projects that the private sector won’t do — or won’t do fast enough and at big enough scale.

So what Democrats need to do is to pivot towards a new economic program that combines Clinton-style neoliberalism and the kind of “development state” common in East Asia. We need fewer ideological crusades and populist kludges, and more competence and capacity. The challenges of today’s world are very different than the challenges of the 90s, and will require some different policies. But Democrats have veered too far away from what worked in the 90s, and that era still has plenty of lessons to teach us.

Basically, if stores are forced to take losses during supply shocks, they’ll have to make more profits during normal times to make up for that. The only way to make more profit during normal times is market power. And the way to increase market power is to increase concentration at the local level, so consumers get charged more. Thus, anti-price-gouging laws will probably exacerbate the very problem they claim to solve.

You really need to do a deep dive on Singapore. I suspect you don't quite understand how it works.

One of my dearest memories was when the head of the American Enterprise institute was invited to give a talk at the National University of Singapore's Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy.

This guy, who was an American, and who had just kind familiarized himself with the vibes of Singapore being a right wing neoliberal place, gave a speech praising its rule of law and laissez faire policy making.

One of the local professors got up and just tore him a new one. Here are the many ways Singapore is very interventionist:

-75% of housing in Singapore is built and owned by the government and only leased to the people.

-Singaporeans have to pay 20% of their income into government mandated savings vehicles. 10% into retirement and 10% into a health savings account.

- ALL Singaporean men have to do National Military Service (or a longer period of Civilian Service) for 2 years

- If you want to buy a car in Singapore, you first have to go and buy a "Certificate of Entitlement" from the government, these are sold by auction and cost about 50,000 Singapore dollars (30-35,000USD) That's just your right to own a car. Then you have to buy the car itself. The car will have to be less than 10 years old to be street legal (There is some small exceptions and rules for classic cars). The TAX on that car will be 100% of the price. This means that if you want to drive a 2023 Honda Accord in Singapore, it will cost you 150,000+ dollars. On the plus side, Singapore's streets have no congestion.

- The government has racial quotas. Things have to happen to keep the ethnic makeup of Singapore consistent (78% Chinese, 12% Malay, 7% Indian, 1-2% everyone else.). Government housing is apportioned in these ratios. New Singapore citizens are naturalized in the same ratios.

-Singapore speech laws are very strict.

- It is NOT ok to be gay legally (Singapore allows it de facto)

Singapore is a very interesting and successful country, but the amount of market interference and government interference is actually very high.

Exactly right. Yes to everything in this excellent piece. When I was the chairman of the Federal Communications Commission 1993 to 1997 our policies exactly fit the prescription here or at least we intended them to.