Why Sri Lanka is having an economic crisis

A textbook currency crisis, triggered by a bunch of policy mistakes.

Americans often don’t even realize a crisis is happening in a foreign country until they suddenly see videos of angry protesters storming government buildings. That was exactly what Americans saw happening in Sri Lanka on July 9th:

I’m not going to go over the details of the political crisis — you can read about that here, here, here, or a variety of other places if you’re interested. Basically the story here is that Sri Lanka has been badly mismanaged, especially by the Rajapaksa family that has dominated the country’s leadership since 2005. The country’s economy is now in a state of collapse, with spiraling inflation and shortages of both food and fuel.

How and why did Sri Lanka’s economy get so bad? Standard explainers list a timeline of policy mistakes, and a series of sudden bad outcomes — sovereign default, inflation, shortages. But without a basic understanding of what these crises are and why they happen, it can be hard to draw the causal connection from A to B; a lot of observers are sort of left with the vague notion that bad things cause other bad things, and eventually everything is bad.

So to really understand what’s going on here, let’s start with the basics — the idea of a currency crisis.

The basics: import dependence and currency crises

Lots of countries depend on imports in order to maintain their standard of living — or, often, simply to live. Food and fuel are generally the most crucial imports — people can do without the latest iPhone, or a new car, but they can’t really do without food and transportation. And since lots of countries don’t have abundant domestic resources of food and fuel, these must often be imported from abroad.

Sri Lanka is a good example of this. About 22% of the calories Sri Lankans consume come from imported food. And fuel is Sri Lanka’s top import. Without imports, many Sri Lankans will quickly find themselves hungry, stranded, and without power.

How do you pay for imports? With foreign currency. Suppose you’re a Sri Lankan and you’d like to buy some wheat from some American farmer. You can’t pay her in rupees; what’s she going to do with rupees? The American farmer needs dollars, to pay rent, to go out to eat, to pay taxes, etc. So you, the Sri Lankan food importer, need to come up with some dollars. If you don’t come up with some dollars, you can’t import the food. Those dollars (or whatever foreign currency you need to buy your imports) are sometimes referred to as foreign exchange, or “forex”.

So where do you get the dollars? Well, you can do one of three things. Either you can swap, you can export, or you can borrow.

1) To swap means you go to the foreign exchange market and say “Here are some rupees, I’d like some dollars please!” And the foreign exchange market trades you some dollars for rupees at some exchange rate, and now you have some dollars.

2) To export means you sell some tea to an American consumer, you let the American pay you in dollars instead of rupees, and instead of going to the bank and swapping the dollars for rupees so you can pay rent or make payroll or whatever, you keep the dollars in a bank and use them to buy some wheat at some point.

3) To borrow means you go borrow some dollars from someone — either a domestic bank who has some dollars sitting around, or from foreigners.

OK, so far so good. But here’s the danger. If your currency gets really weak, it makes it much harder to pay for the imports you need.

What does it mean for a “currency to get weak”? In this case, it means that the value of the rupee goes down, so that you need to give up a lot more rupees to swap for each dollar in the foreign exchange market. If your income is mostly in rupees — as is true for most Sri Lankans — then this makes imports very very expensive.

A weaker rupee also makes it harder to borrow foreign currency. If you have to pay back dollars, but your income is in rupees, and suddenly the rupee gets a lot weaker, then your debt just got a lot more onerous. (And not just new borrowing either, but whatever you borrowed before that you still owe!)

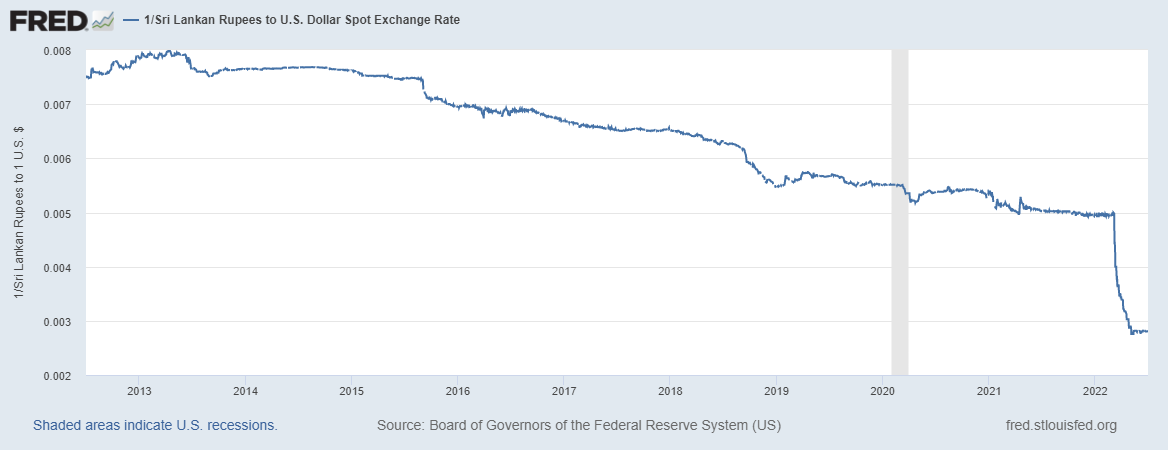

So, this is what happened to Sri Lanka. The Sri Lankan rupee got steadily weaker from 2015 to 2022, and then crashed in March.

A weaker currency makes it much more expensive to borrow and swap to get foreign exchange. That leaves only one good way of getting foreign currency: Exports. If a country runs a trade surplus — that is, if it exports more than it imports — it’s probably OK if its currency gets weaker (we’ll talk about this case another day). But if your country runs a trade deficit, you’re in trouble — you don’t export enough to pay for your imports, and borrowing to make up the difference just got a lot harder.

Sri Lanka runs a large and consistent trade deficit:

So when Sri Lanka’s currency crashed, it was in big trouble. The imports that it relied on for daily life suddenly got a lot more expensive, and because it ran a trade deficit, the only way to get the additional foreign exchange it needed to keep buying those imports was to borrow — but because its currency crashed, borrowing suddenly got a lot more expensive. (This is why a currency crisis is also sometimes called a balance-of-payments crisis.) When the country’s prime minister said last week that the country is “bankrupt”, this is what he meant — it meant there wasn’t enough foreign exchange to pay for needed imports.

So Sri Lankans suddenly couldn’t buy enough food or fuel, and they got mad and toppled the government. That’s really the basic story here, and it’s not an unusual story at all. Currency crises like this are fairly common.

In fact, there are also a couple of other features of crises like these that are very common — and which are present in Sri Lanka’s case. I’ll explain these in the next section.

Macro mistakes: Exchange rate pegs and foreign currency borrowing

There are two things that a lot of countries do in order to get more imports during normal times:

They peg their exchange rates, and

They borrow a lot of foreign currency.

Both of these things are dangerous, because they make a country more vulnerable to a currency crisis like the one described in the previous section. And Sri Lanka did both of these things.

First, let’s talk about exchange rate pegs. An exchange rate peg is a way of keeping the value of your currency at a high level, so your country can easily afford lots of cheap imports. It means the government says “Everyone must trade rupees for dollars at the rate of 200 rupees per dollar”, even if most traders don’t really think the rupee is worth that much.

So what if traders in the foreign exchange market decide to start trading rupees for dollars 350 rupees per dollar? Well then, somehow, the government has to intervene to force the price of the rupee up to 200 per dollar. The way it usually does this is to have the central bank swap a bunch of dollars for rupees in the market every time the rupee gets weaker. This drives the price of the dollar down and driving the price of the rupee up, bringing the exchange rate back to the pegged value. This is called intervening in foreign exchange markets.

Central banks maintain stashes of dollars (actually bonds that they can quickly sell for dollars) in order to be able to intervene. These are called foreign exchange reserves.

Now, if the central bank had to actually intervene in currency markets all the time, it would quickly run out of foreign exchange reserves to sell. But the central bank doesn’t have to actually do this all the time (or at least, not much of it). Usually, traders simply assume that the central bank will do this if necessary, and so they don’t try to trade at a different price. So the exchange rate stays at the pegged level.

But if traders suspect that the central bank is running low on foreign exchange reserves, they may try to “break the peg”, by all selling rupees for dollars at the same time. If the central bank runs out of reserves, it can no longer intervene to support the rupee’s value, and the rupee’s exchange rate crashes very abruptly and you get a currency crisis.

Alternatively, if a whole bunch of people decide to move their money out of the country in a hurry (because they don’t like the way the political/economic situation is headed), they will swap their rupees for dollars or other foreign currencies. This is known as capital flight, also sometimes called a “sudden stop”. Capital flight puts downward pressure on the rupee, and forces the central bank to sell its foreign exchange reserves to maintain the peg. If it runs out of reserves, then bam, the peg breaks, the exchange rate crashes, and you get a currency crisis.

Sri Lanka is a classic case of an exchange rate peg that got broken by capital flight. The country pegged its exchange rate against the U.S. dollar for a long time. Over the last couple of years, capital flight forced the Sri Lankan central bank to spend down its reserves:

The government tried to stop the capital flight, but it failed. When the central bank felt that it no longer had enough reserves to defend the peg, the peg broke, and the Sri Lankan rupee abruptly fell by an enormous amount. This was the currency crisis.

So why is an exchange rate peg a mistake? It’s not necessarily a bad thing — it can help create financial stability. But if you peg your exchange rate at a too-high level, you’re setting your country up for disaster, because any decline in the exchange rate will be sudden and catastrophic instead of slow and gradual. Slow and gradual declines give a country time to reverse course and fix whatever factors are driving down the exchange rate. A sudden collapse gives you no time at all. Thus, exchange rate pegs are very risky.

The second thing a lot of countries do to get more imports is foreign currency borrowing. If you run a trade deficit, you need to borrow to make up the difference — basically if you can’t pay for your imports by selling exports, you have to pay with IOUs instead. Some countries, like the U.S., finance their trade deficits by borrowing in their own currencies — the U.S. borrows in U.S. dollars. This is pretty safe, because even if the dollar’s exchange rate goes down, that doesn’t change the value of the debt relative to the income of the people who have to pay back the debt. Americans make money in dollars and pay debt in dollars, so even if the dollar crashes, that doesn’t make their debts harder to pay off.

But if you borrow in a foreign country’s currency, it’s a lot riskier. If Sri Lankans take out loans in dollars rather than in rupees, they’re taking a big risk. If the rupee gets much weaker against the dollar, it requires many more rupees in order to make payments on dollar-denominated debt.

So why the heck would you ever borrow in a foreign currency? Why wouldn’t Sri Lankans just borrow in rupees in order to pay for their imports? The answer is that borrowing in rupees would be much more expensive. Foreign lenders are afraid that the rupee’s exchange rate will crash and the money they get paid back will then be worth a lot less. So they will charge a much higher interest rate on rupee loans to Sri Lankans, to compensate for this increased risk.

Anyway, Sri Lankans chose to take the cheaper but much riskier option of borrowing a lot of money in foreign currency — mostly in dollars, but also some in Chinese yuan (RMB). This then came back to bite them when their currency crashed. As rupees became worth fewer and fewer dollars/yuan, Sri Lankans had to spend more and more rupees just to make payments on the money they had borrowed earlier:

If you can’t make payments on your debt, what do you do? Well, one thing you can do is default. Private companies can default, and so can the government itself. The Sri Lankan government did exactly this in May, with its first ever sovereign default. But it didn’t default on all its debt, so it may default more in the future.

Another thing you can do to pay off your debt is to print a bunch of money (well, not literally print, but we still use that term). The Central Bank of Sri Lanka can’t print dollars (only the U.S. can do that), and it can’t print yuan (only the People’s Bank of China can do that). The Central Bank of Sri Lanka can only print rupees. But if you print a bunch of rupees, you will probably get inflation. And in fact, Sri Lanka has been getting serious inflation recently:

High inflation makes people very mad, and it also tends to weaken economic growth — making it even harder to pay back debt. Sovereign default also tends to hurt the economy pretty severely for a few years (though countries tend to recover after that). And of course, not having enough food or fuel hurts the economy too. So all these things make it even harder to pay back dollar-denominated debt, prompting more defaults and/or inflation, and the whole thing has a tendency to just spiral for a while.

So far, nothing I’ve described is unique to Sri Lanka. In fact, everything I’ve described here is very common — so common that this type of story is referred to as an “emerging-market crisis”, because this basic pattern happens so often in developing nations (even in weird cases like Cuba). Sri Lanka’s crisis features all of the standard, textbook elements:

An import-dependent country

A persistent trade deficit

A pegged exchange rate

Lots of foreign-currency borrowing

Capital flight (sudden stop)

An exchange rate crash (balance-of-payments crisis)

A sovereign default

Accelerating inflation

If I were writing a hypothetical example of an emerging-market crisis for a textbook, it would look exactly like Sri Lanka’s crisis.

So why then, do most of the stories about the crisis focus on other policy mistakes that Sri Lanka made in the preceding years? Because in the back of their minds, economics reporters already know all the stuff I just explained. Now you know it too! And knowing this will help us understand how those policy mistakes triggered the crisis.

Micro mistakes: The triggers for this particular crisis

The two classic, standard macroeconomic mistakes that Sri Lanka made were to peg its exchange rate too high, and to borrow a lot in foreign currency. Those two errors set the country up for a currency crisis. In addition, there were microeconomic mistakes related to mismanagement of particular sectors of the economy.

Let’s talk about that foreign currency borrowing. One reason Sri Lanka did this was simply to be able to afford more imports — i.e. to live beyond its current means. But another reason was that Sri Lanka borrowed a lot of money from China. China offered Sri Lanka a bunch of cheap infrastructure loans, the biggest of which came as part of the Belt and Road initiative — a major port in the city of Hambantota, which, in what I’m sure is just a coincidence, happens to be the traditional power base of the long-ruling Rajapaksa family. By the 2020s, a pretty decent chunk of Sri Lanka’s loans were from China:

Why does China make loans like this? Well, it results in some pork for Chinese contractors (who come in and actually build a lot of the infrastructure). It probably gets China port access and steady supplies of natural resources. It hypothetically gets China new allies who are grateful for the loans (though this could backfire if the projects go bad). And by lending the money, China limits its risk — unless the borrower country’s whole economy crashes and it has a sovereign default, China gets paid back even if the infrastructure projects don’t pay off.

Well, guess what — the Hambantota port project didn’t pay off. It was an economic failure, mainly just competing (unsuccessfully) with Sri Lanka’s main existing port of Colombo. This forced Sri Lanka to give China a controlling equity stake in the port itself, and left the government saddled with yet more foreign currency-denominated debt. The pundits who confidently warned us that China wasn’t using Belt and Road to create “debt traps” have a bit of egg on their faces right now.

But this was far from Sri Lanka’s only bad business decision under the Rajapaksas. The government dished out a huge tax cut in 2019, hoping that this would stimulate the economy. But it didn’t stimulate the economy very much, and certainly not enough to raise revenues. As usual, Art Laffer was wrong. Falling revenues made it harder for Sri Lanka’s government to pay off its rising foreign-currency debt, setting it up for a crisis.

But the most boneheaded, bizarre mistake that the Sri Lankan government made was a disastrous plan to shift the entire country to organic agriculture. In April of 2021 the government banned the import and use of pesticides and synthetic fertilizers. This devastated Sri Lankan agriculture, since, as it turns out, fertilizer is really really important. Production of tea — Sri Lanka’s main cash crop — fell by 18% in a year. Production of rice — the main food crop — fell by even more.

This debacle did several things. First, by weakening tax revenues, it made the government less capable of repaying debt denominated in foreign currencies. Second, by weakening the economy, it gave Sri Lankans a reason to move their money overseas, which encouraged capital flight and put downward pressure on the rupee. Third, by reducing food output, it forced Sri Lanka to import more food just as foreign exchange was becoming scarce. And finally, because agricultural products are a substantial percent of Sri Lanka’s exports, the devastation of export revenue made it much harder for Sri Lanka to get the foreign exchange it needed to A) keep paying for imported food and fuel, and B) keep making payments on foreign-denominated debt.

I do not understand why Sri Lanka did this very dumb thing. If you want, you can read some backgrounders on why they did this. But what I do know is that this substantially increased the risk of a currency crisis in several different ways.

The organic farming debacle was not the only trigger for the crisis — Covid and a rash of terrorist bombings have combined to devastate Sri Lanka’s tourism industry, another key source of foreign exchange. The war in Ukraine deprived Sri Lanka of yet more sources of foreign currency, since Russia and Ukraine were a big source of tourists for the island nation, and Russia was a big buyer of its tea. Now the economic crisis is hurting tourism even more, of course. And because of all Sri Lanka’s other mistakes that set it up for a textbook emerging-market crisis, Covid, terrorism, and the farming debacle were enough to trigger capital flight, the breaking of the currency peg, the currency crisis, and the downward spiral of default, inflation, and devastating shortages.

So what lessons can other countries learn from Sri Lanka’s crisis? The U.S. isn’t in a similar situation at all, so there are relatively few lessons for us — when we have economic crises, they tend to be of a different variety. But other emerging markets can definitely draw lessons here. First, don’t do boneheaded things like banning fertilizer. Second, be careful about borrowing a ton of money from foreign governments, especially ones like China.

But the best way to make sure you don’t have a currency crisis is to not set yourself up for one in the first place. Don’t run large and persistent trade deficits if you can’t borrow cheaply in your own currency. Don’t borrow a ton of money denominated in foreign currencies. And don’t peg your exchange rate too high. It’s always tempting to play populist and shower your people with underpriced imports in the short term. But in the long term this just never works.

Thank you for this thorough, plain-English explanation of a phenomenon we may be seeing more of in the near term.

> It’s always tempting to play populist and shower your people with underpriced imports in the short term. But in the long term this just never works.

I don't think this is quite true -- I have a feeling the Rajapaksa family is much richer today than otherwise and will continue to be so even if removed from power (just look at the Marcos family in the Philippines or Thaksin Shinawatra in Thailand).

But you'd need to introduce another explainer on the principal-agent problem for that!