The conquest of the post-pandemic inflation is proceeding apace. Core inflation — which is very close to what the Fed actually targets — is down to its 2% target in month-to-month terms:

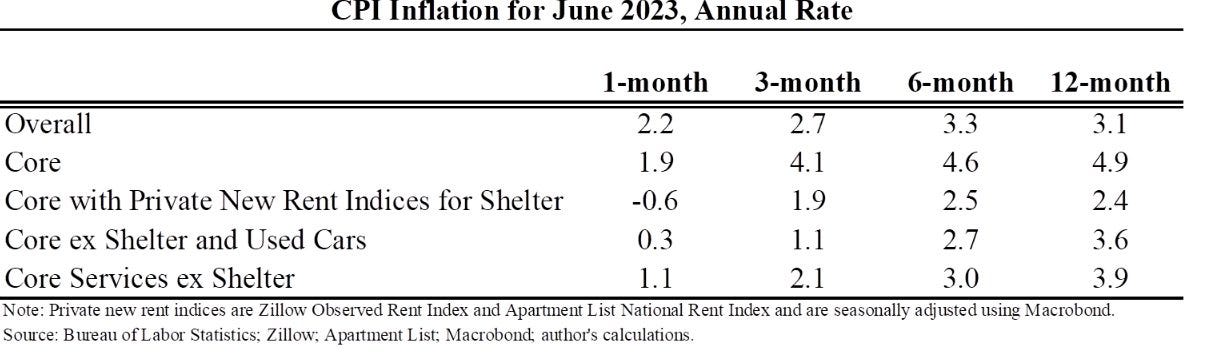

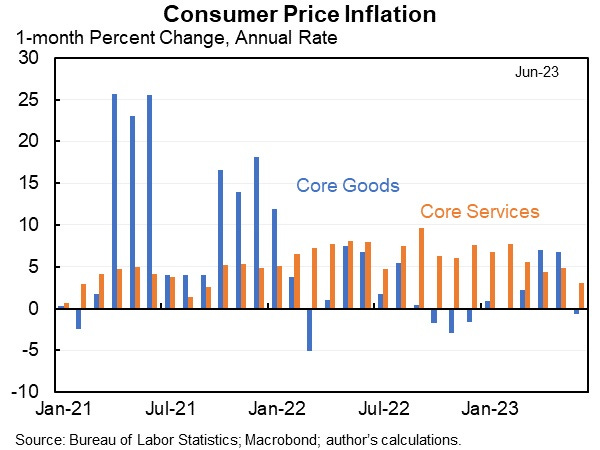

That number will bounce around a bit, but every other inflation indicator we have is also headed in the right direction. Goods actually got cheaper last month, and service price inflation is trending down. Up-to-date rent measures show service prices going down last month as well. Inflation measures that are less sensitive to outliers all show the same trend. Here’s a table showing that basically all inflation measures are headed down, and are nearing the 2% target.:

It’s not clear whether we’ve returned to a low-and-stable inflation regime like what we had before 2020, or whether things will be more volatile for a while. And the scars of two years of high inflation will remain — prices won’t go back down to 2020 levels, and the hit that the American middle class took to their real incomes will take a while to heal. People will continue to be angry about that for a while, I expect.

But I think I’m ready to declare the U.S. successful in terms of halting the wave of inflation that began in 2021. So it seems like it’s time to ask the question: Who got it right, and who got it wrong? Let’s grade the main schools of thought. I’ll go in order from worst to best.

MMT: F

It’s difficult to grade MMT, because it’s difficult to pin them down — their theory studiously avoids making concrete predictions, and instead makes policy recommendations via the pronouncements of a small core of approved guru-like individuals. And of course the MMT people always loudly give themselves a perfect grade; in their eyes, their “theory” can’t fail, it can only be failed. These two things — refusal to write down models that people outside your cabal could test on their own, and insistence that you always got everything 100% right — are giant red flags indicating that a school of thought isn’t backed by solid or interesting ideas.

But anyway, MMT really did seem to take a beating in the court of public and intellectual opinion during the current inflationary episode. In the years before Covid, when inflation was low, MMTers often argued that inflation was the true federal budget constraint (because central banks could just create money to overcome any other budget constraint). When inflation was low and stable, this allowed MMTers to argue for unrestrained government deficits, because no one really imagined that inflation would rise again after being quiescent for decades. When inflation came roaring back after the pandemic, the notion that it had been eternally banished went right out the window.

MMT proponents, who had always focused on fiscal policy, also struggled to deal with a world in which monetary policy had once again come to the fore. This led them to at least temporarily embrace the idea that interest rate hikes would increase inflation:

That’s a really bad idea, as Turkey’s President Erdogan showed. And it pinned the MMT people down to a concrete prediction about the consequences of a policy shift. In fact, we did raise interest rates, and inflation did not rise.

I am sure the MMT people will come up with a (verbose and difficult-to-parse) reason why this, too, somehow represented a triumph for their theories, and will stridently denounce anyone who says otherwise. But in the court of public opinion — which is the only court that matters for an untestable theory that lives and dies by its popularity — this inflationary episode was an unmitigated disaster for MMT.

Bitcoiner hyperinflationistas: D

A lot of Bitcoin people think — or at least, hope— that the U.S. dollar and other fiat currencies will collapse and be replaced by Bitcoin. If the value of the dollar collapsed, we’d see hyperinflation — inflation rates in the 1000% range rather than the 9% range (which is where U.S. inflation peaked in 2021). So Bitcoiners, including many in the tech community, were very vocal about predicting imminent hyperinflation:

Obviously, hyperinflation was not actually happening in 2021. Nor did it ever happen. My friend Balaji Srinivasan, one of the most ardent proponents of the hyperinflation thesis, lost a million dollars betting on the outcome:

Why didn’t hyperinflation happen? Well, it wasn’t entirely out of the question, which is why I gave the hyperinflationistas a D instead of an F. Had the Fed continued to keep interest rates at zero, and had the U.S. government not cut its deficit, it’s theoretically possible that the high inflation of 2020 could have eventually created an expectations spiral, in which every company raised prices again and again in the anticipation of every other company doing the same, because no one believed that the government would do anything to stop it.

But that was not the world we lived in. The U.S. political economy was simply not set up to advance an unrestrained hyperinflationary policy — neither the Fed nor Congress nor the President wanted it, so it didn’t happen. And it would have taken very extreme inflationary policy for quite some time to cause people to abandon the U.S. dollar; the U.S. government would have had to be in a very chaotic state, and it just wasn’t.

Furthermore, the Bitcoiners’ model of Bitcoin’s own value was probably wrong as well — the cryptocurrency hasn’t been behaving like “digital gold” or an inflation hedge. Instead its value seems to go up when the economy is strong, like a tech stock. Even in the extremely unlikely event that the U.S. had collapsed into chaos, it’s unlikely that Bitcoin would have benefitted in the long term, because its primary enthusiasts would be impoverished and the digital infrastructure that supports it would be degraded.

Anyway, not much reason to dwell on this one much more. The Bitcoiner hyperinflationista model of the global economy is just not a good model of how things work, and if you believe in that general model, the recent inflation should give you a good reason to reevaluate.

Polycrisis: D

“Polycrisis” is the notion that the world’s economic problems are mutually reinforcing. The concept, popularized by Adam Tooze, has become popular among a wide array of investors, writers, and activists. (Balaji even cited “polycrisis” in his bet with Medlock!) The typical way of representing the supposed “polycrisis” is to draw a detective-board-like chart in which various problems are connected to each other. Tooze did some of these, but the real champion was the World Economic Forum, which released the following chart:

I’ve drawn red boxes around the two “nodes” that I think correspond to inflation. The gray lines on the graph suggest that the WEF believed that inflation was being driven by:

burst asset bubbles

debt crisis

natural resource crises

supply chain collapse

black markets

state collapse

employment crises

the erosion of social cohesion

Now, some of these were real drivers of inflation (which is why I gave “polycrisis” a D rather than an F). Supply chain collapses, increased deficits, and the oil price spike all probably did contribute to the inflation of 2021-22. But some of these connections make no sense. Burst asset bubbles are deflationary; anyone who lived through 2008-9, or who has studied the Great Depression or the Japanese bust of 1990, should know that. Also, the inflation of 2021-22 coincided not with an employment crisis, but with very high employment levels in the U.S. (As for “state collapse” and “erosion of social cohesion”, their inclusion here merely seems to buttress the notion that “polycrisis” is more a form of negative news overdose than a coherent theory.)

But in any case, the recent fall in inflation seems to buttress my own counterargument against “polycrisis”. I argue that many of the world’s problems mutually counteract each other. China’s recession, caused by that country’s real estate collapse, has reduced demand for natural resources, and thus helped bring down oil prices and reduce inflation around the world. Russia’s war in Ukraine has forced it to keep pumping as much oil as it possibly can, and selling it at cut-rate prices to China and India, who now form a sort of “reverse OPEC” along with the West. This has also helped bring down inflation. And the busts in the stock, real estate, and crypto markets that happened as a result of interest rate hikes have helped restrain demand, further contributing to the conquest of inflation.

So “polycrisis” mostly failed here because its assumption that crises reinforce each other ignored the fact that they often cancel each other out.

Team Transitory: C-

When inflation rose in 2021, there were a number of people who declared themselves “Team Transitory”. They argued that inflation would soon go away without the need for substantial monetary and fiscal tightening, because it was the product of temporary problems with supply chains that had been disrupted by Covid and would work themselves out in short order.

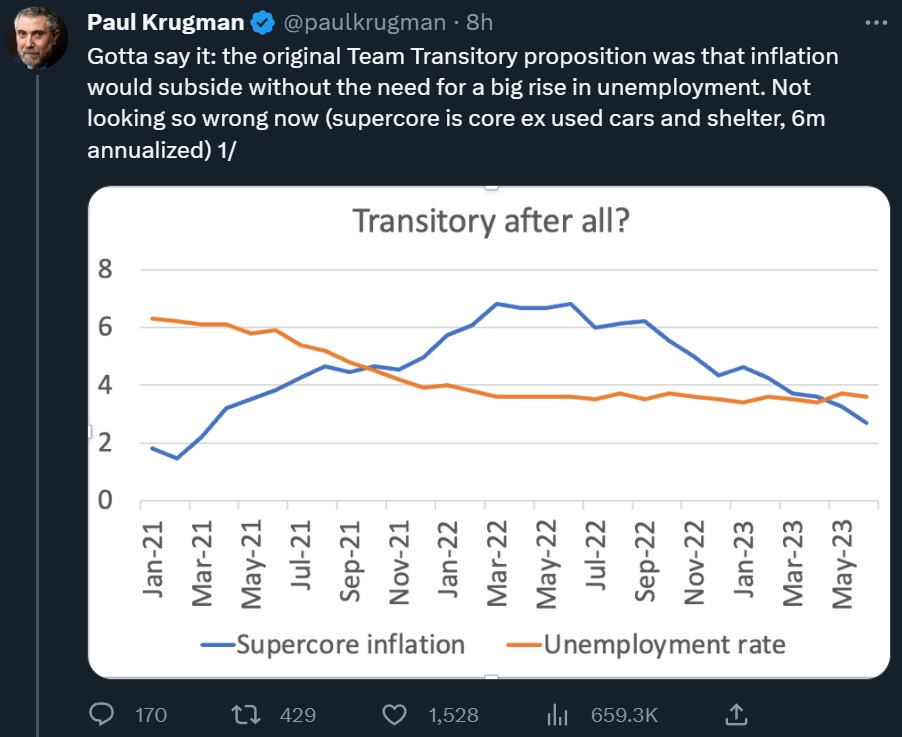

Now, with inflation falling, some of the people who declared themselves Team Transitory are declaring victory. I will pick on Paul Krugman, because as the world’s top econ pundit, he can take it:

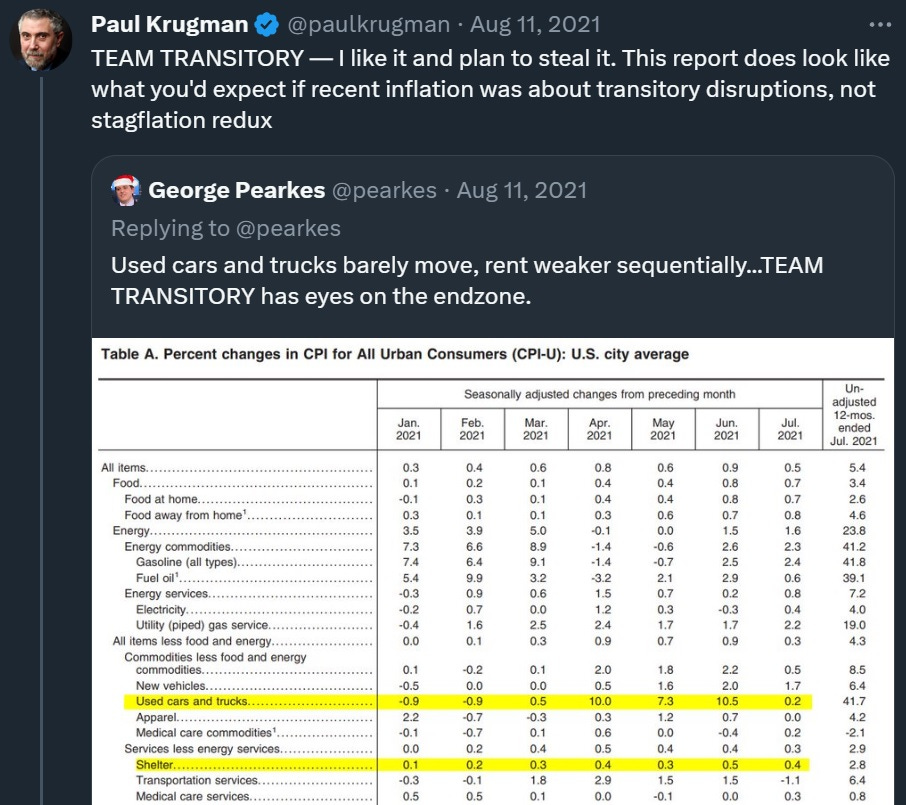

But back in 2021, Team Transitory made much stronger claims than what Krugman is saying here. First of all, they claimed that inflation was limited to a few commodities, and that this was a sign that it was due to supply chain disruptions:

But in late 2021, inflation spread to become very broad-based. Services inflation was always significant, and took over from goods inflation as the main contributor in 2022:

The notion that this was just some transient supply-chain disruptions that was only affecting specific products was absolutely central to Team Transitory’s claims in the summer of 2021. And that was incorrect.

Team Transitory also called the end of the inflation at least a year and a half too soon:

So let’s not rewrite the historical record here. Team Transitory’s claims were a lot stronger than simply the idea that the sacrifice ratio (i.e., the amount unemployment would rise when beating inflation) was low.

Now, to be fair, Team Transitory had no way of anticipating the Ukraine War, which caused a temporary burst of high oil and food prices that contributed a lot to inflation in 2022. And that did turn out to be transitory. And the eventual rationalization of post-Covid supply chains probably did exert some disinflationary effect. So they didn’t entirely whiff here. They just greatly overstated their case. And their complacency in 2021 probably fed into the Fed’s decision to delay the start of rate hikes until 2022, which in retrospect looks like a serious mistake.

Greedflation: C-

I wrote a post about the “greedflation” idea fairly recently, and if you’re interested you should read that:

To make a long story short, “greedflation” proponents believe that monopoly power exacerbated or caused the inflation of 2021-22. This is questionable, since monopoly power was similarly strong in 2014-2019, and yet we saw no burst of inflation despite a strongly growing economy. But it’s possible to claim that monopoly power made the economy less responsive to demand and supply shocks in 2021-22, and thus made the inflation worse than it otherwise would have been.

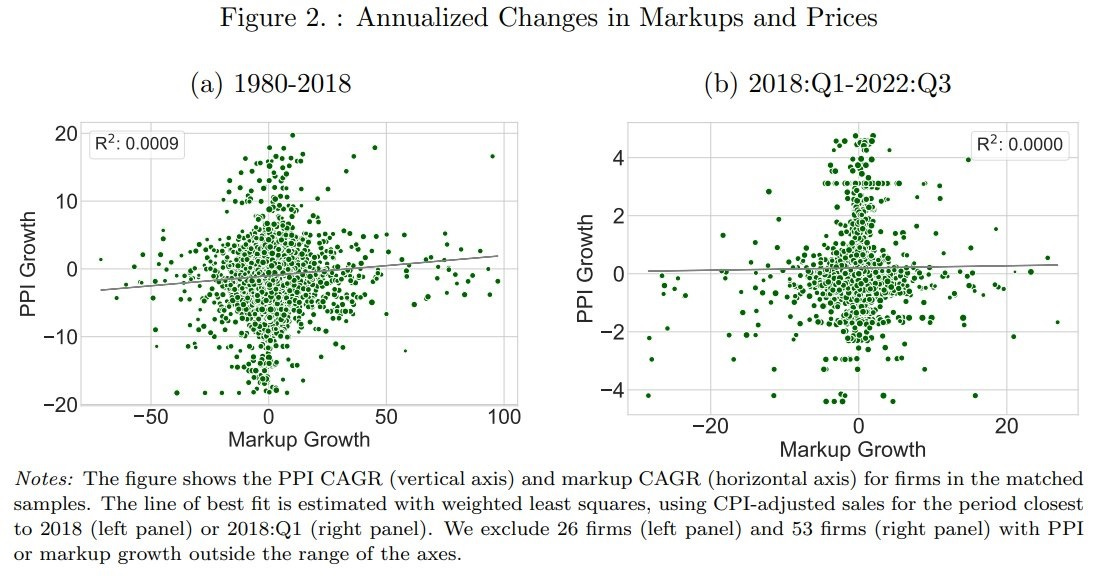

That’s a plausible claim, but so far there’s not much evidence for it. When greedflation proponents say that profits “caused” inflation, they typically just show that both profits and prices rose in 2021-22. But that’s correlation, not causation; it could easily just be that supply and demand shocks drove prices higher, and that companies merely reaped a passive windfall from that, without any change in their behavior or market power. When we look at changes in markups (which are closely related to profit margins), we see that these weren’t correlated with price changes at the industry level:

So the companies doing the most price-raising weren’t more likely to be the companies getting fatter profit margins.

It’s also possible that companies forecast that their costs would go higher in the future, making their surge in profits temporary, and chose to raise prices to offset those future costs. This is the explanation put forward by Glover et al. (2023) at the Kansas City Fed. Oddly, many greedflation proponents have cited that paper as support for their thesis, even though it directly and repeatedly disavows the idea.

But the greedflationistas did get one thing right, and I think they deserve credit for it. The joint U.S.-European price cap on Russian oil has probably been helpful in breaking the power of the OPEC cartel and bringing down oil prices since late 2022. OPEC is definitely a monopoly, and is definitely very greedy. And oil prices have definitely been an important driver of inflation since early 2022. So this one targeted price control on a key commodity controlled by a greedy monopoly did probably contribute to the conquest of inflation.

Mainstream macro: A-

So far, I haven’t given any of these schools of thought a particularly good grade. If none of them got it particularly right, who did? The answer is a bit surprising: It was good old mainstream macroeconomics.

Mainstream macro is basically a synthesis between the ideas of John Maynard Keynes and Milton Friedman. It’s pretty boring, vanilla stuff — it says that when you raise interest rates and/or reduce budget deficits, inflation and economic activity go down, and when you lower rates and increase deficits, inflation and economic activity go up. And it says that you can also get supply shocks like rises in oil prices that make this tradeoff worse, meaning that economic activity will be lower for any given amount of inflation.

Mainstream macro’s first victory was in predicting that the inflation would happen in the first place. In February 2021, Olivier Blanchard used a very simple “output gap” model to predict that Biden’s Covid relief bill would raise demand by enough to show up in the inflation numbers. His prediction came true. He didn’t get everything right — he thought wages would rise more than consumer prices, and he neglected the lagged effects of Trump’s Covid relief packages and Fed lending programs. But his standard simple mainstream model got the basic prediction right when most people made the opposite prediction, and this deserves recognition.

More importantly, mainstream macro appears to have gotten policy right. We raised the federal funds rate further and faster than at any time since the 70s, and engaged in other forms of monetary tightening as well. And we cut budget deficits sharply from where they were in 2020 and 2021:

These were exactly the things that any boring undergrad mainstream macro textbook would tell you to do in the face of inflation. And…it seems like it worked, didn’t it? We did what the textbooks said, and inflation went down. Hurray!

In fact, the main criticism that people are lobbing at mainstream macro here is that this victory wasn’t costly enough. Unemployment didn’t rise significantly, as many mainstream macroeconomists predicted would happen as a result of monetary and fiscal tightening. But this seems like an odd criticism, doesn’t it? If a general says he can take a city but it’ll cost 2000 casualties, and you grimace and say “OK, go ahead,” and he takes the city with only 100 casualties, do you fire that general? I’d say no, you give him a medal.

Now, you could use the surprisingly good labor market as a reason to doubt that the Fed and Congress had anything to do with the conquest of inflation. You could say “Rate hikes and deficits don’t actually affect inflation that much, and it was all just oil prices, so mainstream macro is a cargo cult that just waves its arms and pretends it’s controlling stuff.” And it would be hard to disprove you, because definitive evidence is very scarce in the world of macroeconomics. Or you could say “Rate hikes do work, but they take 2 years to work, so in another year we’ll have an unnecessary recession.” And in this case we’ll just have to wait til 2024 to see whether your prediction is borne out.

But as of right now, it looks like the Fed and Congress, with an assist from falling oil prices, have pulled off the most elusive and sought-after Holy Grail of macroeconomic stabilization — the costless disinflation. And even if the economy does cool off a little bit in the months to come, it would still be in the goldilocks region of a soft landing. You can’t really ask policymakers — or macroeconomic theorists — to do any better than that.

So if there’s a significant recession next year, then we can reevaluate mainstream macro’s performance in the inflation of the early 2020s. But as of right now, it’s looking far better than any of the alternatives proposed over the last two years, so it gets the highest grade.

Update: Note, by the way, I would caution against identifying “mainstream macro” with Larry Summers, as some people do. I know Larry is someone you see a lot in the news, and he’s mainstream in some ways, but outside the mainstream in others. In particular, mainstream models mostly rely very strongly on the effect of expectations. If policy changes like rate hikes work by changing people’s expectations, it means that if you raise interest rates, you can get a very quick response in terms of taming inflation, possibly without hurting the economy much (because everyone just coordinates on a new, lower rate of price hikes). Whereas I think Larry takes a more “hydraulic” view of the economy, where rate hikes work mainly by throwing a bunch of people out of work, which then weakens demand, and only then do prices come down. Interestingly, Summers’ view on what it takes to defeat inflation is probably closer to that of left-leaning people outside the mainstream; the main difference being that he’s more hawkish than them in terms of how much he worries about inflation.

The fact that inflation started coming down about 6 months after the Fed started hiking rates — which is about what the academic literature would predict — seems like a win for the expectations-based view that I would identify as “mainstream”, rather than Summers’ more hydraulic view. Then again, that’s also about when oil prices started falling, so it could just be a coincidence. Welcome to macroeconomics! Anyway, what Powell and the Fed did was probably closer to what a typical academic macroeconomist would recommend than to the more hawkish path that Larry Summers recommended.

A D is too good for the crypto folks. They're a stopped clock that's been predicting hyperinflation since there was crypto in the first place

I would suggest an F+ for the Bitcoiners, because they actually made a prediction that was falsifiable. As you pointed out the chances of hyperinflation in the United States are vanishingly low. In fact, in my admittedly limited experience, Bitcoiners seem to be wrong about everything all the time.