Examining an MMT model in detail

A repost from my old blog

MMT, for those who aren’t familiar with it, is a small, cohesive group of people who go around telling the government to borrow more and spend more. It stands for “modern monetary theory”, which implies that there’s a theory of how the economy works. So far, when economists have looked into the MMT literature, they’ve concluded that it’s less of a cohesive theory than a meme — a set of arguments for a specific policy, rather than a fully laid-out description of how the economy works. (The MMT people, whose rhetorical style is heavy on scorn and social media aggression, naturally allege that the economists simply haven’t given them a serious reading.)

In any case, MMT garnered a lot of interest back in 2018, when it won the ear of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and the Sunrise Movement. But recently, interest in the group and their ideas has begun to wane:

In recent months, as inflation has risen, some have started to claim that MMT has been discredited. This is because MMT people generally claim that the only possible negative result of excessive government spending is inflation, and…well, we spent a lot of money and now we’re seeing inflation. The MMT people, of course, beg to differ, arguing that inflation is transitory, that it’s not caused by fiscal policy, and that it’s best addressed through direct government intervention in the markets where prices are rising, rather than through interest rate hikes (This latter piece is where MMT differs from its predecessor, the theory of Functional Finance, which holds that fiscal austerity is the right way to control inflation.)

In any case, I thought this would be as good a time as any to re-up a post from my old blog in which I examined an MMT model in detail. MMT doesn’t make a lot of quantitative, concrete models — it usually relies on a combination of wordy explication and politics-infused online pugilism. But occasionally it does, and taking a look at an MMT model helped clue me in to what the ideology is all about. It also left me with plenty of questions, as I point out at the end.

Warning: This one gets a little wonky.

What is MMT, the heterodox economic theory that has captivated Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, made its way into the Green New Deal discussion, and inspired dozens of thinkpieces and critiques? What does it say? How can we tell if it's a good theory or a bad one?

These are incredibly important questions. Thanks to Ocasio-Cortez and the Green New Deal, MMT has very quickly gone from an obscure heterodox idea to one of the most potentially influential and important theories in all of economics.

Formal Models vs. Guru-Based Theories

These days, most economic theories are collections of mathematical models. If you want to know what the theory says, you can parse out the models and see for yourself. You don't have to go ask Mike Woodford what New Keynesian theory says. You don't have to go ask Ed Prescott what RBC theory says. You can go read a New Keynesian model or a Real Business Cycle model and figure it out on your own.

MMT is different. There are many wordy explainers and videos that will explain some of the concepts behind MMT, or tell you some of MMT's policy recommendations. But that's different than having a formal model of the economy. In a criticism of MMT, Thomas Palley writes:

The critical economic policy question is what does the power to money finance deficit spending mean for government’s ability to promote full employment with price stability? This question can only be answered by placing that power within a theoretical model and exploring its implications...Proponents of MMT have a professional obligation to provide [a simple mathematical] model to help understand and assess the logic and originality of their claims. Yet, [MMT proponents Eric Tymoigne and L. Randall Wray] again fail to produce a model...If MMT-ers did produce a model, I am convinced the issues would become transparent, but readers would also see there is “no there there”.

Now, a lot of people like to criticize mathematical models in economics. And they do have their drawbacks. Economists can sometimes become so entranced by the precision of math that they ignore the need to connect that math with the real world. And the difficulty of hacking through math can lead economists to make the models too simple.

Furthermore, Palley is being a bit too strict in demanding math; formal models can be stated in English or in graphs, rather than in equations.

But formal models have important advantages. For one thing, a good formal model can be compared with quantitative data, to see whether it works or whether it fails. Formal models can make testable predictions.

A second advantage of formal models is that you can figure them out for yourself, without having to ask any gurus. If you have to run to the gurus to ask them what the theory says any time you think you've found a flaw, it becomes almost impossible to skeptics or outsiders to evaluate the theory objectively.

This latter issue comes up a lot when dealing with MMT. In a recent post, Brad DeLong expresses his frustration with the theory's apparent slipperiness:

"Functional finance" is a doctrine originated and set out by Abba Lerner...When I said that "functional finance" is at the core of MMT, I got immediately smacked down by one of the gurus...Perhaps the key to the eagerness of [L. Randall] Wray to dismiss me (and James Montier) for saying that MMT is Lerner+ is sociological. Perhaps MMT is not model-based ("IS-LM with a near-vertical IS curve") and not idea-based ("Functional Finance") so that it can be guru-based. (emphasis mine)

It wasn't just DeLong and Montier who conflated MMT with Functional Finance. Aryun Jayadev and J.W. Mason did something similar in their attempted write-up of MMT, leading Josh Barro to do the same thing in his own criticism of MMT. Mason, Jayadev, and Barro criticized MMT on the grounds that raising taxes to control inflation - something you have to do in Functional Finance, and which some MMT advocates agree is necessary - is politically very difficult.

But in response to these critiques, Mason, Jayadev, Barro, Montier, and DeLong were told: No, MMT's approach to fiscal policy is not just Functional Finance. It is very very different. On Twitter, MMT insider Rohan Grey declared that MMT has other tools besides fiscal policy for fighting inflation. On his blog, MMT insider L. Randall Wray said that MMT's main tool for maintaining price stability is the federal Job Guarantee:

Yes, MMT does have another tool to maintain price stability. It is the JG approach to full employment. It has always been a core element of MMT. We have never relied the simplistic version of Functional Finance that was presented by Mason. It would take about five minutes of actual research to demonstrate this.

Now that's a perfectly fine rebuttal. People get theories wrong all the time. It's perfectly possible that Mason, Jayadev, Barro, Montier, and DeLong were all very wrong to conflate MMT with Functional Finance, and that five minutes of actual research would have demonstrated this.

But which five minutes? If you want to know how MMT's price stabilization policy differs from Functional Finance, where do you look? Do you trust Wray's blog? Or Grey's tweets? Or an online explainer? Or a video explainer? Or in one of the many papers written by MMT proponents? Which one?

Because MMT doesn't often include formal models, the question of how MMT thinks inflation works is very difficult to answer for yourself. The same is true of a number of other questions, such as how MMT's Job Guarantee would create full employment with price stability. You have to go ask the MMT People themselves.

But "few formal models" doesn't mean "no formal models". Occasionally, MMT people do write down a formal description of how they think the economy works (or might work). One example is "Monopoly Money: The State as a Price Setter", by Pavlina R. Tcherneva.

Examining an MMT Model (or, "Pavlina Tcherneva and the EMPL of Doom")

"Monopoly Money: The State as a Price Setter" explains the idea of how a Job Guarantee would work. The formal model begins on p.130 (page 7 of the PDF).

Here is the model's "conceptual framework":

The government demands that people pay taxes in dollars, which you can only get by working for the government. So people work for the government because that's the only way they can pay their taxes.

Now let's look at exactly how people work for the government and pay their taxes:

Already I can see one potential problem with this model, which is that everyone in the entire economy dies.

Note the part that I've marked with a red arrow. This economy produces only one service, which is firefighting. But you can't eat firefighting. So if that's literally the only thing anyone does in this economy, everyone will starve to death.

LOL OK, so that's probably too harsh. Maybe the people in this economy are doing other stuff on the side that's not in the model - farming, manufacturing, etc. After all, Tcherneva does mention that T could be "a property tax", and the model doesn't include property. So let's assume there's other stuff outside the model too, so that people don't starve, or freeze, etc.

But that still leaves the question of why the government needs firefighting services in the first place. What if there aren't any fires? If the government hires more firefighters than it needs to actually fight fires, then it's just wasting resources - making people labor in useless toil, taking them away from subsistence farming, or whatever. The more useless firefighters it hires, the poorer each person is. (In the limit, if every person has to spend all their time and effort doing unproductive work for the government, they actually do starve to death!)

Anyway, let's go on.

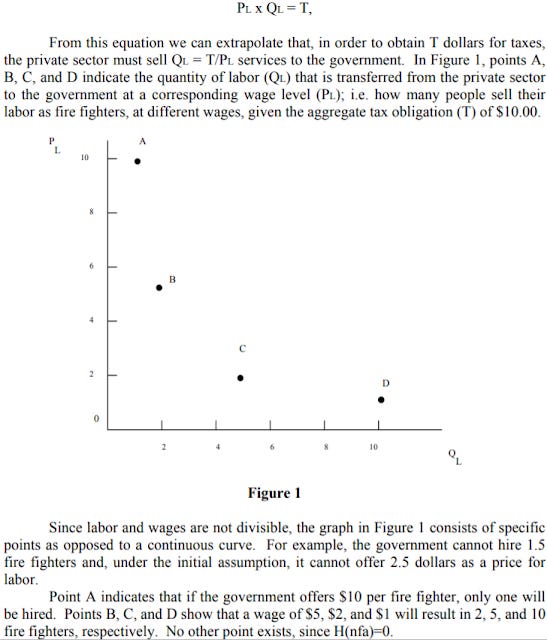

So the government can hire 1 firefighter for $10 or 10 firefighters for $1 each, etc. (cents apparently don't exist in this world, so you can't hire 4 firefighters for $2.50 each, which is weird but OK).

Another question arises: Why is anyone willing to work as a firefighter in this model? According to Tcherneva, they need dollars to pay their taxes. But who pays the taxes? Tcherneva specifies that the tax bill "for the entire community" is $10. But how is this tax bill paid? Does the entire community file taxes jointly?

Suppose the government chooses to hire only one firefighter - call her Susan. She gets $10 for firefighting, and everyone else gets $0. Does the government tax Susan $10 and tax everyone else $0? Apparently so. Because Susan has $10 and everyone else has $0, so the only way the government can get its $10 is to tax Susan $10.

So why does Susan go fight fires in the first place? Firefighting takes work. If instead she decides to be one of the 9 people who don't work as firefighters, she can relax and watch Netflix, or farm food, or go do whatever it is that people in this model do when they're not firefighting. Someone else will get the dollars, someone else will pay the taxes. Because if you don't work as a firefighter your tax bill is zero, because you don't have any dollars to tax!

So taxation in this model doesn't make a lot of sense, because the model doesn't explain who actually pays the taxes. Without knowing that, it's hard to know why people would accept the government's prices for their firefighting services.

But OK, there must be some reason they work. Maybe the government makes people work at the price it offers. In this case, people are effectively doing slave labor for the government.

That sounds bad...right? It sounds a bit like colonialism, when European governments would send their armies to Africa or Latin America or India and make the locals labor for their overseas masters.

At this point you may be saying "Noah, you jerk, why are you slandering the MMT people by equating their ideas with colonialism? That's not fair!" But I have a good reason for drawing this comparison: Tcherneva makes it herself, earlier in the paper! European colonialism in Africa is explicitly held up as a successful example of a "tax-driven currency":

On p.135 (page 12 of the PDF), Tcherneva explicitly states that the case where the government sets prices for firefighters "is the African example." So yes, it's explicit that in the model where the government sets prices, it also sets quantities - i.e., it forces people to work.

I don't want to editorialize too much here, but "the African example" seems bad. Forced labor, potentially to the point of genocide, does not sound like the kind of "job guarantee" I would want.

Does Tcherneva offer any alternative? Yes. In her "case 2b" on p.134 (page 11 of the PDF), she relaxes the assumption of forced labor, and allows the price (and therefore also the quantity) of workers to be set by the market. She also allows for the possibility that labor unions might organize to reduce the amount of labor they do in exchange for their tax dollars:

In this model, the government can't determine how much labor it gets or how much each laborer gets paid; it can only determine the total number of dollars it pays for labor. In fact, as Tcherneva suggests, labor unions might even allow workers to get all the government's dollars for a very small amount of labor - good for workers, but bad news if there really is a fire!

Anyway, this new model sounds much less horrifying, but it still doesn't answer the fundamental questions of "why do we need all these firefighters" or "who exactly pays the taxes". But at least it does allow for the possibility that either market forces or organized labor could minimize the amount of potentially-useless labor people were compelled to perform for the government in exchange for the money they need to pay their taxes. Colonial Africa, but with labor unions.

(Tcherneva also develops some further cases, including one where the government purchases park benches and another in which desired net saving is nonzero. But none of these cases answer the basic questions either. But don't take my word for it; check the paper.)

Anyway, this formal model is very useful, because it allows careful, precise, explicit analysis of MMT ideas. It allows us to identify potential problems with the theory, such as the question of whether a job guarantee would represent unproductive toil, and whether that's something we would want as a society.

Further Questions for MMT

There is much I do not yet understand about MMT, that I would like to understand.

For example, suppose the government implements a job guarantee and sets deficits, credit policies, etc. at the appropriate level to ensure price stability, but we still have more inequality of income and wealth than we would like? What policies should then be used to reduce inequality, without interfering with the goals of price stability and full employment?

Also, I would like to know how to test MMT empirically. What concrete predictions - about macroeconomic aggregates or other quantities - does MMT make that would allow us to determine whether it describes the economy better than, say, Old Keynesian IS-LM models, or New Keynesian models with financial frictions?

Also, how does MMT model productivity in the economy? It seems like hiring a bunch of firefighters in the absence of fires would negatively impact productivity and reduce living standards. Does MMT assume that productivity is exogenous, does it assume that productivity reductions will always be of secondary concern relative to the importance of full employment, or does it have some other way of dealing with potential hits to productivity?

I'm not confident in my ability to answer these and other important questions by reading L. Randall Wray blog posts, or long online explainers, or wordy MMT papers. I want to be able to read a concrete, formal, well-specified model like the Tcherneva model above, and answer these questions myself. And the rest of the non-MMT econ deserves this as well.

Man, I hadn't heard that a serious MMT-er had held out African forced labor as an example. This reminds me of Scott Alexander's fairly persuasive argument that a "job guarantee" almost certainly leads into a scenario where you have second-class citizens who are stuck working those guaranteed jobs in order to survive at subsistence, while the first-class citizens continue to work in the normal market.

This is why we should have UBI, not a jobs guarantee. UBI says that you're allowed to live at subsistence while NOT working -- which you might just do indefinitely, but it won't be comfortable, so most likely you'll still be looking for work. The point of UBI is precisely to make sure that nobody faces the choice between tolerating a shitty, coercive employer, and suffering some dire consequences (homelessness, hunger, or even worse, their children experiencing the same).

As an occasional MMT dabbler I might be able to explain some of the stuff around taxation you were wondering about above. I think the usual MMT way of thinking here is that things work like this:

1) government says all ten people in the economy will need to pay $1 in taxes each (for a total of $10).

2) We hire Susan as a firefighter and pay her $10.

3) The other 9 people in the economy need to provide some good or service to Susan in order to get the $1 they owe the government.

4) boom, now you've got a market economy.

I think in reality you'd want to spend more money into the economy than you plan to tax back out, at least until you achieve the right level of liquidity. So the government might hire two people to do firefighting, injecting $20 into the economy, but still only tax $10 out, leaving the extra $10 behind to continue circulating.

My understanding (maybe wrong) of the idea here though is that we think of government spending as creating money, and taxes destroy money. So the government doesn't pay for things with taxes - in an MMT model, taxes are simply collected and burned in big bonfires, and then as a completely separate action, the government prints new money and spends it into existence.