The end of the "vibecession"?

Maybe people are being irrationally pessimistic. Or maybe it's just all about real wages.

One constant source of frustration for econ writers and economists is that the connection between public perceptions of the economy and the actual state of the economy isn’t clear. That doesn’t mean the connection doesn’t exist, or that people’s perceptions are just vibes. What it does mean is that it’s often hard to design economic policies that make people happy.

For example, take inflation numbers. Economists tend to have two ways of reporting inflation: month-over-month or year-over-year, representing how much prices have gone up over the last month or the last year. When both of these numbers go down, economists throw up their hands and say “Yay! We beat inflation!”

But if you’re a regular person, this may not necessarily be what you care about. After all, prices have still gone up 15% since the start of this inflation two and a half years ago! The price rises now may have moderated, but that increase in prices that we just endured is not going to reverse itself. If you owned any bonds at the start of 2021 (or at least, bonds with a fixed nominal interest rate), those bonds have been permanently devalued. The reduction in the real purchasing power of your paycheck from that burst of inflation might not be fully reversed soon either. Etc.

Now, you may react to this by saying: OK you silly economists, if you’re not measuring what people care about, then dang it, measure what people care about. It’s as simple as that! And yet it’s often very hard to figure out which economic numbers people actually care about; remember, the example above is just a hypothetical. To make matters worse, people’s opinions of the economy may only be loosely or inconsistently related to any actual economic numbers that we can measure.

For example, take the “vibecession”. For about a year and a half now, many commentators, forecasters, businesspeople, and economists have predicted that the U.S. economy was about to head into a recession. In fact, according to the rule of thumb that a recession means two consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth, we did have a recession in the first half of 2022, back when Putin invaded Ukraine and oil prices went through the roof, even though the National Bureau of Economic Research, who is in charge of these things, never officially called a recession. But regardless of what you want to call it, the U.S. labor market barely paused, only to recover in late 2022:

And GDP growth has also recovered. Some people still think that the rate hikes that the Fed did over the past year or so will ultimately push us into a recession, but they’re pushing back the expected date, and some are now saying it won’t happen at all (or at least, not until we get hit by the next unexpected catastrophe).

In a relative sense the U.S. economy is doing better than almost any other developed countries, both in terms of GDP growth since the start of the pandemic, and in terms of bringing down inflation since mid-2022.

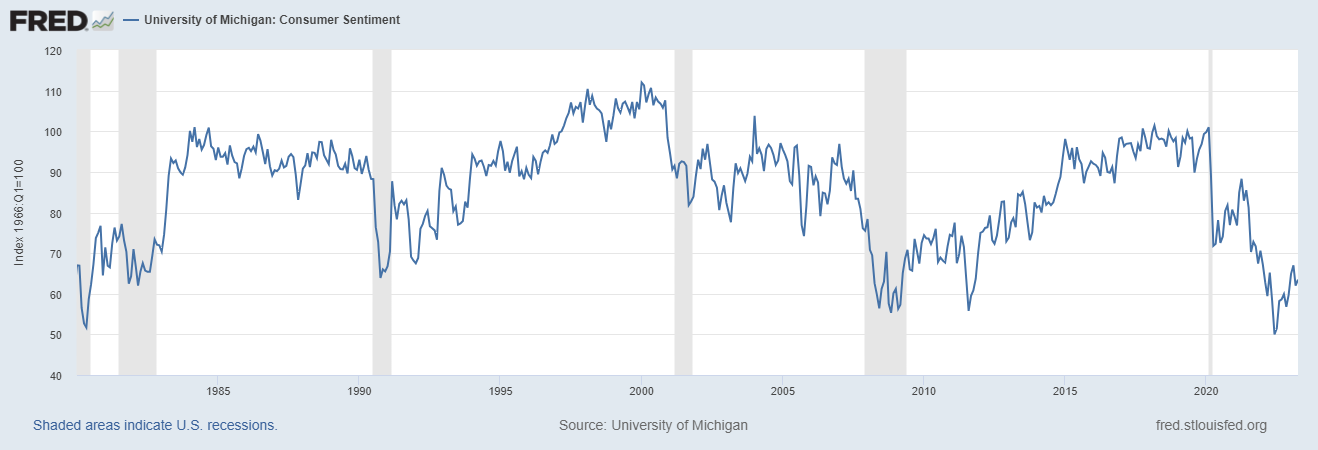

So given all of this encouraging economic data, you’d think most Americans would be pretty upbeat about the economy. In fact, they’re not. Consumer sentiment is just about the lowest it’s been since 1980, and is at about the same level as the depths of the Great Recession. There has been a slight rebound since mid-2022, but it’s tiny:

It’s not just that one survey, either. Pretty much every survey finds that Americans think the economy is absolutely terrible. Here’s Gallup:

How can we make sense of this? We have the best labor market since the 90s, falling inflation, and yet people think we’re in the middle of one of the worst economic catastrophes in modern history? What???

Kyla Scanlon has labeled this phenomenon the “vibecession”. People feel like there’s something off about the economy, even though by most of the measures economists use, there’s really not. So far, it’s all just vibes.

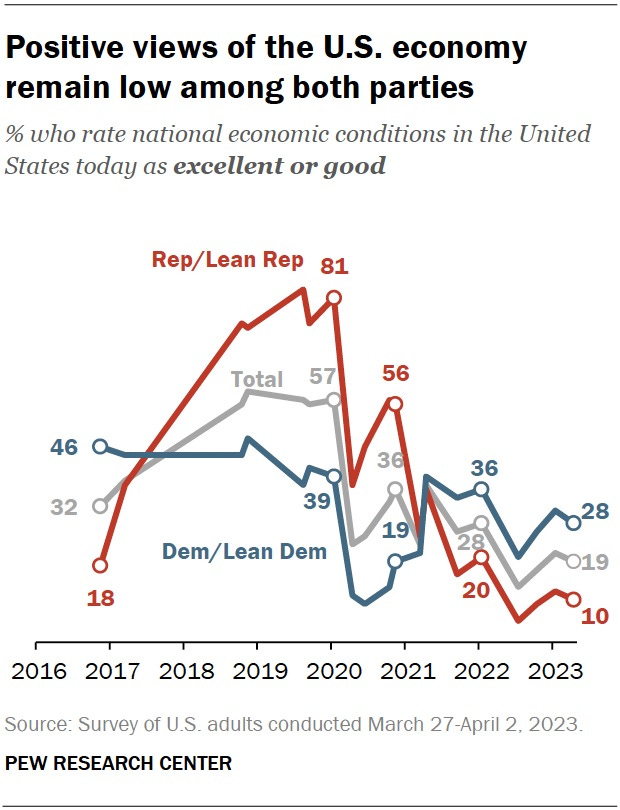

You might think this was a function of partisan gaps — Republicans might simply be unwilling to acknowledge how well the economy is doing when there’s a Democrat in the White House, especially after the bitter unrest of the past few years. But nope. There is a partisan difference, but it’s relatively modest; Dems also think the economy is worse than under Trump:

One complicating factor is that even though they think the economy is going to Hell in a handbasket, Americans tend to feel their own economic situation is pretty good. As Derek Thompson has noted, people tend to be very positive about their own financial well-being, moderately positive about their local economy, and negative about the national economy:

A caveat here is that this kind of survey response can be heavily biased by what people think they ought to tell the survey taker. People may be too proud to admit they’re struggling economically, or they may think it’s bad form to claim personal hardship; instead, they may just express their personal worries in their assessments of the national economy.

Anyway, the vibecession is still a mystery that needs explaining. We could pretty easily come up with a lot of theories — the impact of a negativistic news media, PTSD from the pandemic, lingering pessimism over the state of American society in a time of unrest, and so on. Any and all of these might be real factors, and we may never really know; in fact, some historians like Rick Perlstein believe to this day that economic pessimism in the 70s was more about social unrest than inflation.

Alternatively, it might be something really simple that’s just hard to extract from the available data. For example, negative economic sentiment might be a long-delayed reaction from Covid, or a rational forward-looking prediction of a recession that might fail to materialize out of sheer luck. These explanations might be more to an academic economist’s taste, but they’re every bit as ineffable and unprovable as the vibes-based theories.

But there is actually a fairly simple explanation for the vibecession that broadly does fit the facts, and is supported by some research. Darren Grant has a new paper entitled “The Great Decoupling: Macroeconomic Perceptions and COVID-19”, in which he aggregates a bunch of historical measures of economic sentiment, and correlates these with objective economic conditions. After rejecting a number of hypotheses, he explains economic pessimism in the years since the pandemic as being a function of falling real wages:

A decoupling of real wages from macroeconomic fundamentals could cause economic perceptions to become decoupled from these fundamentals as well…

Across…age groups, the highest wage growth is experienced by the Young, who are generally the most positive about economic conditions. With age comes reduced wage growth and increased pessimism. Similarly, within two of these three groups, Middle and Older, sentiment improves when wages rise faster, with correlations that equal or exceed those quoted above…

During the pre-Covid economic expansion, real wage growth varied substantially from one year to the next, and optimism about the economy varied accordingly, generating points that hug the trendlines fairly closely. In 2020 came Covid, and sentiment plummeted in all three age groups…In 2021 and 2022 unemployment and GDP growth normalized but real wages fell substantially. Economic perceptions fell right along with them…[L]ow real wage growth alone explains most of the drop in sentiment during those two years. This decline is not irrational, but a reflection of the inability of wages to keep up with inflation.

If there’s one economic measure that has been unprecedentedly bad in the years since the pandemic, it’s real wages. Since the end of 2020, real hourly compensation has fallen by more than it has in America’s entire postwar history. Not even in the inflation of the 1970s or the Great Recession of the late 2000s and early 2010s did compensation fall so much:

As Matt Yglesias recently noted, this decline may now have been arrested. The compensation data is quarterly; average hourly earnings, which don’t include benefits, are monthly, so we’re able to see some more recent details. And we can see that the fall in real hourly earnings halted after summer 2022, when inflation started to come down and growth recovered. But still, if you just sort of draw a line to extrapolate the pre-pandemic wage trend, real wages are way below what they would have been if that trend had continued.

In other words, despite a very recent, very slight recovery, Americans have seen themselves working more and more for less and less money over the past two years. Darren Grant’s data, along with older surveys by Robert Shiller, suggest that real wages declines are what people really really really hate about inflation.

We can theorize about the psychology of the vibecession all day long, but maybe in the end it was just a wagecession.

And if so, maybe we should be cautiously optimistic, because real wages seem to be rising again, even if only slowly. But in the meantime, we shouldn’t be surprised if people continue feeling grumpy about a seemingly booming economy for a while to come.

In Germany, our public TV 8 pm news show always ends with reading out the German equivalent to the Dow Jones, and sometimes gives one or two "explanations" on why it changed, like "the DAX closed 0,6% down today. Experts consider this a consequence of tumultuous oil prices". It does this more than 2 hours after the stock market has closed, so this procedure has only one purpose: send grandpa Joe to bed with a good vibe. "Hmm, the DAX is up, that's probably good (for me)".

This is precisely how I feel about the GDP. I am not gross, I am barely domestic and I don't make products. This has nothing do with me. My wage hasn't increased in 6 years, and wages have uncoupled from productivity 50 years ago.

Real wages are a much better attempt at trying to approximate how I am actually affected by the economy, but it irks me to see that even top economists consider it appropriate to use line graphs here. Why are you lacking the ambition to work with distributions here? The real problems are always in the top and bottom percentiles. To put it vulgarly, starving single mothers don't average out.

I am sick and tired of these line graphs, it's like trying to figure out how a football match went by listening to the noise-levels from outside the stadium. Yeah, you will probably notice all the goals and maybe even figure out which team won, but coaching a team solely based in this information? Good luck.

Give distributions or nothing please. We have the data, and economists are both smart enough to work with them, and to properly explain them to their audience. Well, maybe not to the bottom 10%, but those guys will average out.

Well, knock me over with the feather! Real wages are what really matter?! I'll be damned!

You mean when my social security check Remains the Same or grows only a few percentage points and the price of gas goes up like it suddenly did and at the same time I go to the grocery store and broccoli and apples are way up and landlords are jumping on the opportunity to raise rents and blame it on bidenomics that I get negative about the economy? A 15% drop in real wages has the same effect on my mood as if prices stay the same in the boss cut my wages by 15%.

Meanwhile we have a party that refuses to lay any plans on the table because Mitch is afraid that people will pick them apart but they have a lot to say about what actually happened under a democratic Administration. Mitch, the purpose of laying those plans on the table is so that we can take advantage of the first amendments provisions and talk about it. Talk about what's happening talk about how it feels talk about what we might be able to do about it.

I'm sure it's a lot more fun to talk at the top of our lungs about hunter's laptop and culture wars than to calmly and rationally discuss real issues, like immigration policies, climate change, preparing for another pandemic, social justice and equal opportunities for women and minorities.

Hopefully a time will come when we can realize that a culture is only as useful as the environment it is trying to adapt to and Nostalgia is not a policy and the fifties are over. Let's take advantage of our diversity and get as many perspectives as possible on all our problems, because that's the only way we're going to solve them. And the biggest problem of all right now is a threat of an authoritarian government taking over and sidelining all those voices and turning it all over to one person who's main Talent is marketing when we are a nation of immigrants with their new ideas and new energy and appear to love America more before they ever get here and some people who are born here and don't realize that democracy is how we got here.