Biden did stuff, and it looks like it's working so far

Only one President has taken actual concrete steps to address U.S. industrial weakness vis-a-vis China.

For the first time in its entire history, the U.S. is facing a rival that can out-manufacture it. This is a very big deal. George W. Bush and Barack Obama never seemed to recognize how big of a deal this was, and so we lost valuable decades in which we could have addressed this problem.

Donald Trump did recognize it — or at least, he seemed to dimly understand that manufacturing strength was important for national competitiveness, and that China was a threat. But Trump didn’t actually do much about it — his export controls on Chinese companies were modest and partially reversed under pressure, his tariffs did nothing to bring back U.S. manufacturing, and his occasional haphazard attempts to encourage FDI came to naught. Trump brought needed attitude shifts, but was utterly ineffectual in actual real policy terms.

Then Joe Biden came into office, and — with help from appointees like Jake Sullivan and Gina Raimondo — actually made a serious attempt to do something about America’s industrial weakness vis-a-vis China. His approach had four basic pillars:

Industrial policy (the CHIPS Act and the Inflation Reduction Act) to encourage American manufacturing in strategic industries

Export controls on semiconductors and semiconductor manufacturing equipment being sold to China

“Friend-shoring” and reshoring of supply chains, especially of critical minerals

Tariffs on various Chinese products

It’s too early to tell whether tariffs have had an effect, since these were a very late addition to the playbook. Friend-shoring has made some progress, though it will take a decade and a half to really see results, and domestic mining is currently being stymied by land-use regulations. In the areas of industrial policy and export controls, though, we’ve seen some pretty rapid signs of important progress.

Frustratingly, this progress has been mostly ignored by the national political conversation, even though it’s one of the most important things that the American government is doing. A lot of this subject is probably too wonky and technical for most people, and foreign policy tends to get less air time than domestic policy. Even knowing all this, however, I’m a bit frustrated at how few people are talking about how the Biden administration finally did something about America’s industrial weakness, after so many years of inaction.

So anyway, here’s a quick rundown of the results that Biden’s policies are getting so far.

Industrial policy is succeeding in building factories

The idea behind Biden’s industrial policy is that there are external threats — Chinese military aggression, and climate change — that the market will not address on its own. Therefore the government must intervene in order to secure American supplies of technologies that are critical to fighting these threats.

Semiconductors are a crucial input into every form of military technology, and high-end semiconductors will be crucial for the autonomous weapons that are expected to take over the battlefield in the coming years. Green energy — especially solar power and batteries — are crucial in the fight against climate change, but batteries are also the power source for FPV drones, which are becoming the indispensable weapon of the modern battlefield. Energy in general is also an input into every technology, so having U.S. energy supplies dependent on Chinese production is a bad idea.

Thus, Biden’s two big signature industrial policy bills — the CHIPS Act and the IRA — address semiconductors, batteries, and solar power.

So far, both bills have achieved an important result: For the first time in decades, America is now building factories at a rapid rate. Now, it’s important to realize that building factories is different than producing actual stuff. Factories, once built, can sit idle if there’s no demand for their products, or if they can’t find sufficient workers. So there’s no guarantee yet that Biden’s industrial policy will succeed at cranking out actual chips and batteries — it’s just too early to tell. But the factories are getting built, and that’s about all we could hope for at this point.

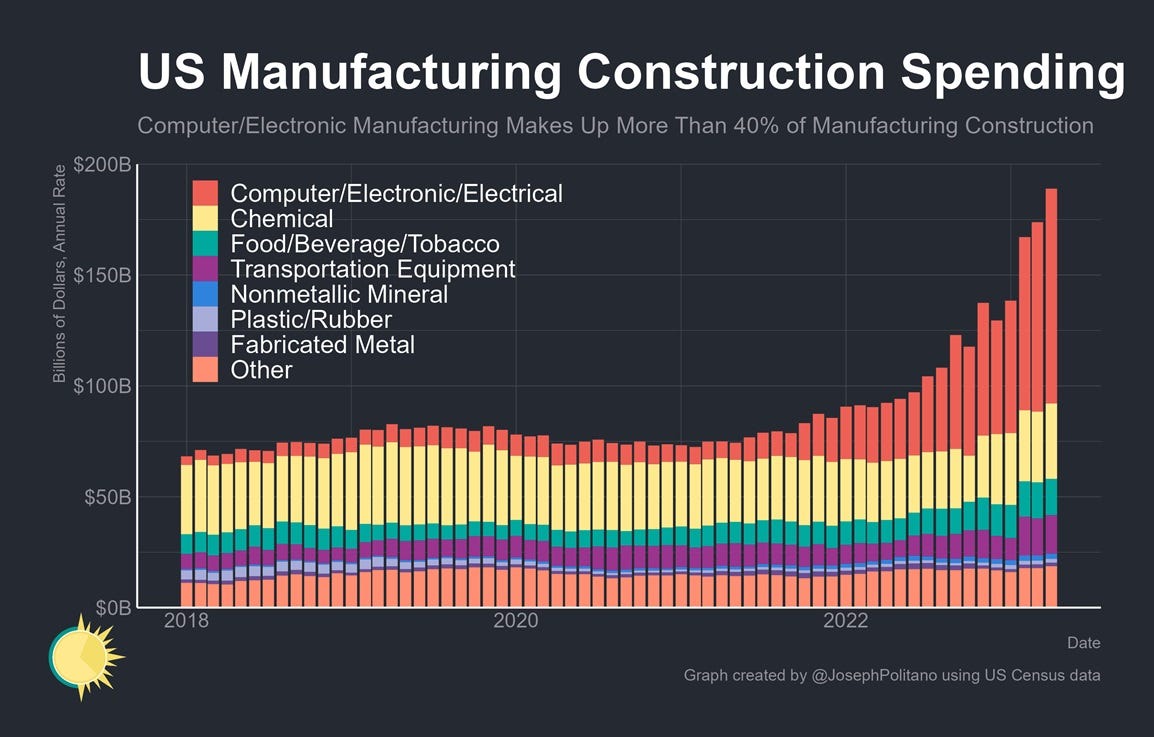

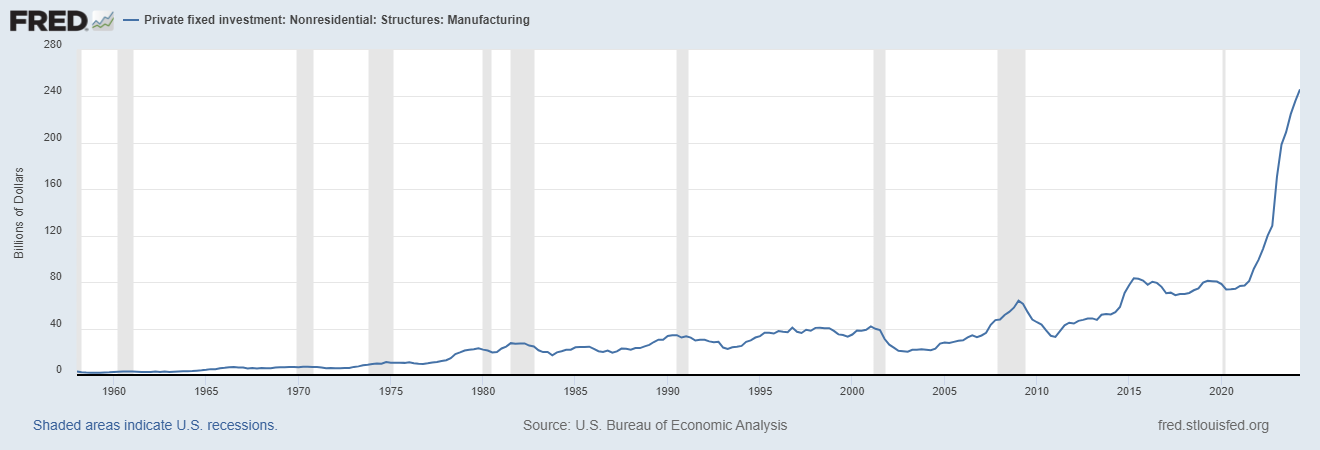

Let’s look at some numbers. First, here’s factory construction spending in the U.S., in terms of actual dollars:

That’s pretty impressive-looking! Of course, some of this is eaten up by the rising cost of building factories in America (which includes inflation). So let’s divide that number by the price index for “new industrial building construction”:

The chart is only since 2008, because unfortunately the price data only goes back that far. But you can see that even after accounting for the increased price of factory construction, the U.S. still spending more than twice as much on factory construction compared to the Trump or Obama presidencies.

That’s a huge change! Now let’s look at what types of factories are being built:

It’s practically all in the “computer/electronic/electrical” category, which includes both semiconductors and batteries — the two main things Biden subsidized. And there’s a smaller bump in the “transportation equipment” category, which mainly means cars — which the IRA also subsidizes.

So this is really a smoking gun. Biden’s industrial policies have created a massive boom of private manufacturing investment in the most strategic industries. In fact, the amount of private investment utterly swamps the amount of actual government spending commitments. Here’s a somewhat helpful chart:

Now, don’t let this chart fool you into thinking America is spending a lot more on chip manufacturing than China — the green bar represents only Chinese government spending, which is more than 3x as big as the CHIPS Act. Chinese private (or “private”) companies are pouring in a lot more. But what this chart does show is that private investment in chip manufacturing in America absolutely dwarfs government spending. For just $52 billion in subsidies — almost none of which has even been spent yet — we got $834 billion in private investment. (Note that that number is over several years, not just one year.)

The revival of American manufacturing is being prompted by the government but not bankrolled by the government. A small injection of subsidies is really all it took.

So far, these factories haven’t come online — they take a number of years to build. We don’t know if they’ll actually be able to find the demand for their products — or the workers. But industry leaders and consultants are predicting an increase in market share for the U.S. in the crucial field of leading-edge chips, as well as more modest market share gains in other areas, even taking China’s own massive investments into account:

That’s from an excellent Bloomberg report by Mackenzie Hawkins on the state of the CHIPS Act, which includes lots of details about the challenges that still lie ahead.

Importantly, the CHIPS Act — which was passed with Republican assistance in the first place — may be gaining durable bipartisan approval. Some GOP lawmakers are embracing the policy, and some conservative intellectuals are thinking about how to put their own spin on the policy if they come to power.

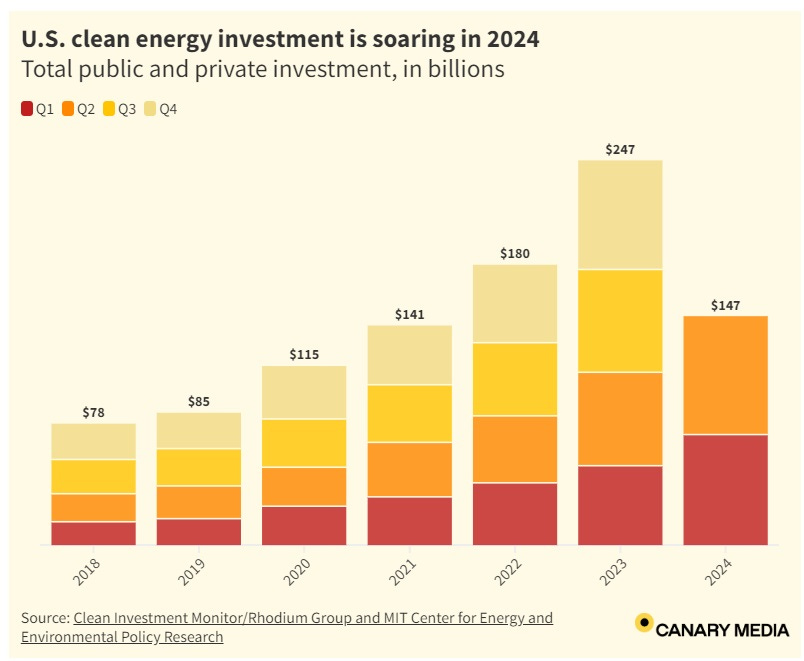

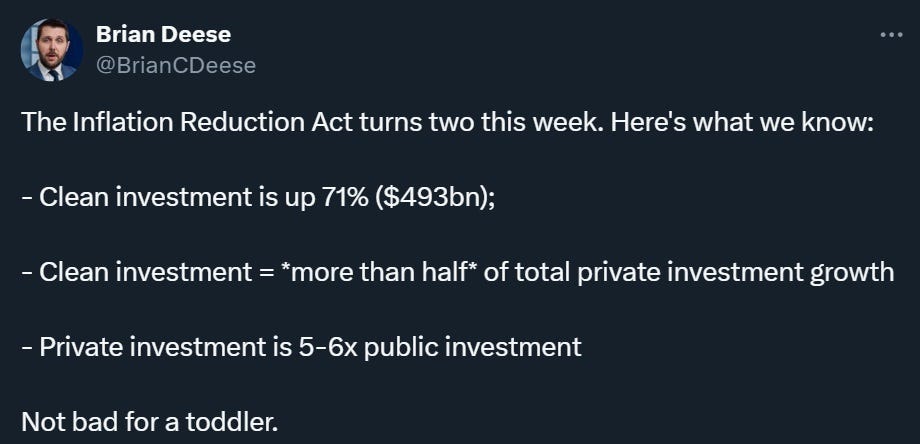

Now let’s look at the IRA and clean energy. U.S. investment in the area was already rising, because solar and batteries just got so darn cheap. But the IRA seems to have supercharged things:

Note that the 2024 bar is shorter because it only includes the first two quarters of the year — observe the growth in the red and orange bars! That’s very rapid growth.

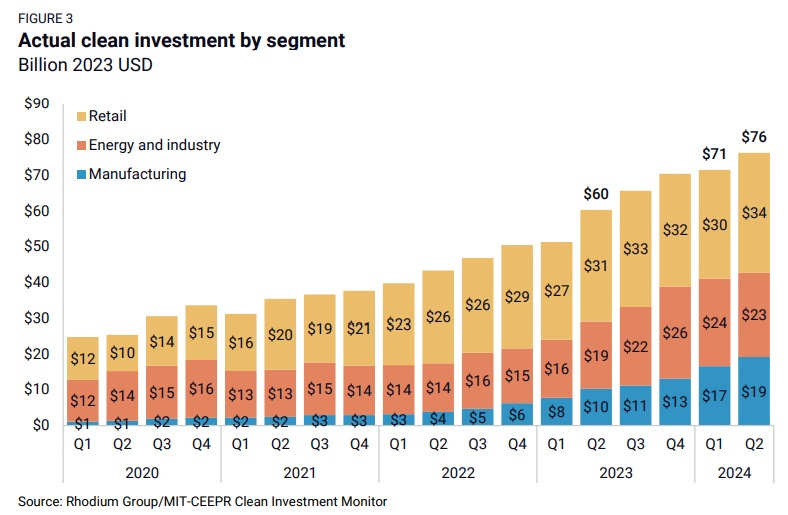

Also realize that this chart doesn’t just show factory construction, like the earlier ones I posted. This is investment in clean energy as a whole, which includes battery factories and batteries, solar panels and solar factories, etc. So that’s a lot. Here’s a breakdown:

These numbers come from a report from the Clean Energy Monitor, entitled “Tallying the Two-Year Impact of the Inflation Reduction Act”. Again, highly recommended.

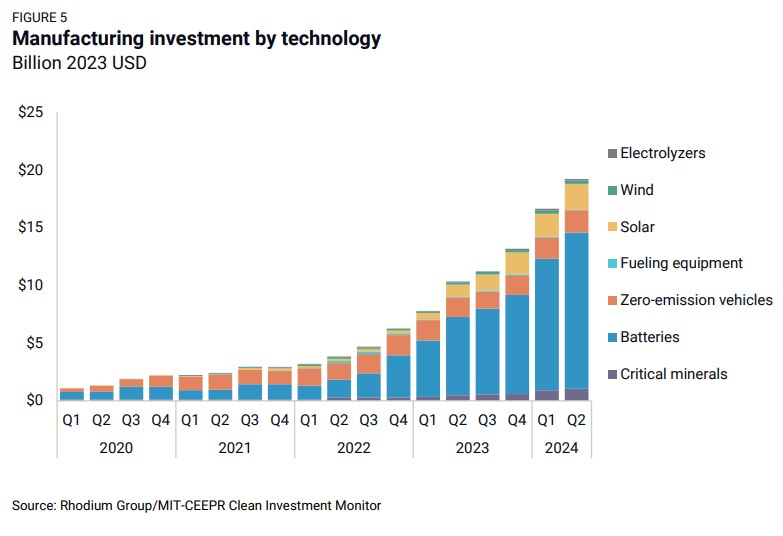

The report notes that while America is spending a lot on battery factories, we’re not spending much on solar factories:

Part of this is because batteries are a much more strategic industry than solar — batteries go into weapons, while solar power doesn’t. So it’s probably OK if we buy our solar panels from China (which is one reason we shouldn’t have tariffs on that product).1

As with the CHIPS Act, we see that a relatively small input of government money has prompted a much larger boom in private investment:

Finding enduring political support for the IRA investments will be harder than for the CHIPS Act, because Republicans tend not to care about clean energy — recall that the IRA, unlike the CHIPS Act, was passed without bipartisan support. But one big reason for hope here is that the IRA is focusing investment in red states:

Even more importantly, the IRA — even more than the CHIPS Act — is creating jobs. Clean energy employment in the U.S. is growing at around 4% a year, faster than overall employment. The boom is concentrated in the car and car parts industries:

A lot of investment plus a lot of jobs for red states will hopefully lead the GOP to want to preserve the policy. Already we’re seeing a few Republicans start to stick up for it.

Biden’s industrial policy has come under criticism from several sectors — from free-marketers who don’t like industrial policy for ideological reasons, from political opponents, and from China boosters who don’t want to see America compete with China. A lot of these critics look fairly silly, because it’s obvious that they’re jumping the gun.

For example, in March, Matt Cole and Chris Nicholson confidently declared that “DEI killed the CHIPS Act”, citing a reported delay in TSMC’s fab construction project in Arizona. But by the time their op-ed came out, TSMC’s dispute with the Arizona construction unions was already resolved. Then shortly after the op-ed came out, CHIPS Act subsidy awards were announced, and suddenly TSMC announced that their Arizona project was back on schedule. The critics were obviously waiting to pounce on a policy they didn’t like, and their poor timing revealed their lack of circumspection.

The truth is that the U.S. is new to industrial policy, and it will take time to get the kinks worked out — the idea is to see what works, and learn from mistakes. That will require a sustained effort and lots of course correction along the way. Fortunately, the government has been closely monitoring the companies it subsidizes, making sure their projects are on track before writing them their first checks, and making sure they’re meeting milestones before sending follow-up checks:

The White House plans to begin disbursing Chips and Science Act grant funds by the end of the year, after finalizing discussions with chipmaker recipients…The talks include seeking reassurance that Intel Corp.'s projects…are moving forward, despite the company’s recent announcement that it’s slashing 15% of its workforce…Payment tranches are based on construction and production milestones…The rigorous, multi-stage application process is meant to ensure projects meet federal requirements and that taxpayer dollars are used wisely[.]

Free-marketers may wince at this sort of close cooperation between the government and the private sector, but plenty of history shows that this how a lot of big manufacturing efforts get done.

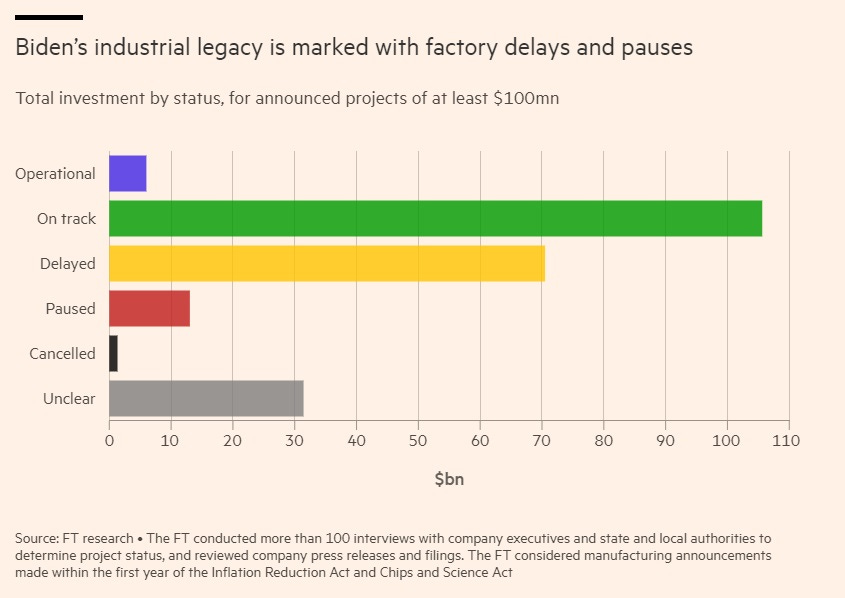

The other big criticism of Biden’s industrial policy is that it will be stymied by America’s insane land-use regulations. This is, admittedly, a big danger. But again, the critics are obviously jumping the gun in their eagerness to declare industrial policy a failure. For example, here’s the Financial Times, a British newspaper:

Some 40 per cent of the biggest US manufacturing investments announced in the first year of Joe Biden’s flagship industrial and climate policies have been delayed or paused, according to a Financial Times investigation…of the projects worth more than $100mn, a total of $84bn have been delayed for between two months and several years, or paused indefinitely, the FT found…The delays raise questions around Biden’s bet that an industrial transformation can deliver jobs and economic returns to the US[.]

But the FT simply set its expectations too high. As economist Jonas Nahm explains, delays are incredibly common for this type of manufacturing effort. The fact that a majority of projects are still on track, and only a few have been paused or cancelled, is actually an extremely good record:

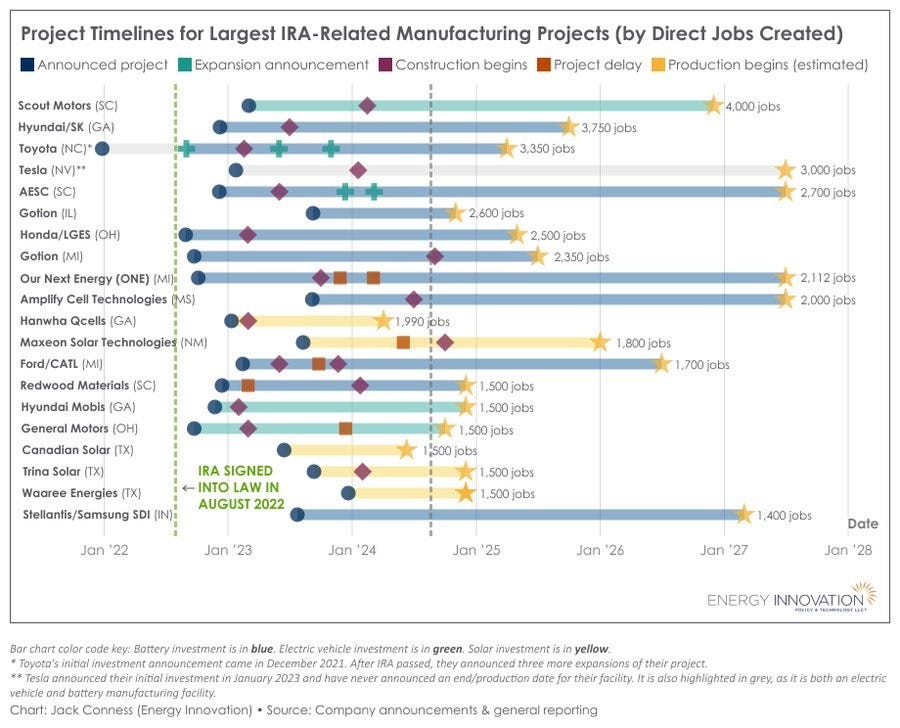

And Jack Conness, who has actually built a dashboard to track IRA and CHIPS Act construction projects, notes that almost all such projects are expected to be completed in a reasonable time frame. Here’s a chart for the 20 largest IRA-related projects:

So far, this is a pretty incredible record of success. I say “so far” because once again, it’s not over until the products are rolling off the lines in large numbers. But things look very much on track, and probably better than anyone would have dared to hope at the start of the effort.

Industrial policy hasn’t yet succeeded, but it looks like it’s succeeding so far.

Export controls are hurting China’s chip industry

Another big piece of Biden’s plan to establish a U.S. industrial edge over China is export controls on chips and chipmaking equipment. Unlike industrial policy, this isn’t the kind of thing that will create American jobs (although it may preserve a few). It’s a destructive policy, aimed at keeping China a step behind the U.S. and its allies when it comes to the all-important autonomous weapons race, and hopefully in the area of precision weaponry in general.

In a roundup back in July, I noted some signs that the export controls appear to be having a major effect, despite the loud boasts of China boosters that the controls would only accelerate China’s indigenous industrial development:

When Huawei came out with a 7nm chip in late 2023, many hailed it as a sign that export controls had failed. Recall that U.S. export controls were designed to make it a lot harder for China to make anything smaller than 14nm. This was followed closely by Huawei announcing that it was testing a way to make 5nm chips — very close to the best that Intel can make — using older equipment not covered by the initial round of export controls. To China boosters, at least, the collapse and failure of U.S. export controls seemed complete.

But in fact, the export controls have quietly been having a significant effect. Huawei’s Ascend 910B chip, an AI-training chip that the company claimed was a rival to Nvidia’s, uses a 7nm process. And according to new reports, fully 80% of the Ascend 910Bs are defective, and China’s foundry SMIC is having trouble making them in large volumes…Recall that the Kirin 9000S, Huawei’s famous “sanction-busting” phone processor chip, that is also made on a 7nm process by SMIC. This raises the question of whether that chip will face similar production problems…

This is exactly how export controls were supposed to work! They were not supposed to immediately shut off China’s ability to make advances in semiconductors; instead, they were supposed to erode the country’s competitiveness, slow it down, and keep it a step behind. So far, it looks like export controls are succeeding at that goal.

Meanwhile, Huawei appears to be pessimistic about its chances of making even small batches of even better chips[.]

The policy still faces its critics. For example, Mary Hui wrote an article in April entitled “Huawei’s sanctions-beating strategy”, noting the company’s resurgent profits and apparent chipmaking success. The WSJ concurred, issuing a report in July entitled “The U.S. Wanted to Knock Down Huawei. It’s Only Getting Stronger.”

But these cries of triumph ignore the corrosive effect that export controls are having on Huawei. As Keith Krach and Jonathan Pelson report, Huawei’s resurgence has mainly come from within China, which may come at the long-term cost of orphaning China’s electronics product standards from the rest of the world — a problem that was known as Galapagos Syndrome when it happened to Japan. Krach and Pelson also note that Huawei’s resurgent numbers are probably the result of heavy — if often secret — government subsidies. Furthermore, as noted above, yields on Huawei’s chips appear very low, meaning that continued subsidies will be needed to keep the production lines rolling.

And recall that Huawei is far from the only target of the export controls. A very large number of Chinese semiconductor companies have been failing over the last few years — most recently, the Chongqing-based Xiangdixian.

These are not happy headlines — it’s sad for Chinese entrepreneurs to see their businesses fail and for Chinese people to be thrown out of a job. And this is not going to yield direct benefits for U.S. businesses, either — in fact, there will inevitably be costs. These include Chinese retaliation, such as the country’s recent export ban on gallium and germanium, which are used in the production of chips and solar panels. Western companies like ASML, Lam Research, and Nvidia will also inevitably suffer a bit from reduced sales to China. Export controls are really more of a military policy than an economic one — and like in war, there will be casualties on both sides.

(China, for its part, probably should have thought about this before launching an all-out multi-decade campaign of government-supported economic espionage in order to destroy all non-Chinese high-tech manufacturing industries and replace them with China’s own, in order to facilitate geopolitical dominance of Asia and the globe. Just saying.)

Anyway, the successes of the export control regime so far don’t mean that the job is done — far from it. The Biden administration has been constantly looking for new ways to tighten up the controls, even as China searches frantically for cracks and loopholes. One new move may be to restrict Western companies from being able to repair and maintain the chipmaking machines that they already sold to China before the export controls went into effect:

The Netherlands plans to limit ASML Holding NV’s ability to repair and maintain its semiconductor equipment in China, a potentially painful blow to Beijing’s efforts to develop a world-class chip industry…The government of Prime Minister Dick Schoof will likely not renew certain ASML licenses to service and provide spare parts in China when they expire at the end of this year…The decision is expected to cover the company’s top-of-the-line deep ultraviolet lithography, or DUV, machines…

The Dutch company’s chip-making equipment, the most advanced in the industry, is sold with maintenance agreements that are essential to keep them running. Withdrawing such support could render at least some of them inoperable as soon as next year…Without ASML’s DUV gear, it will be increasingly difficult for Chinese technology champion Huawei Technologies Co. and its partner Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corp. to make breakthroughs in their current capability[.]

Like industrial policy, export controls are a technique that gets constantly refined over time as the people implementing it learn how to do it more effectively.

And as with industrial policy, export controls seem to be having an effect, even as U.S. leaders prepare to refine the strategy. Biden’s policies haven’t yet restored American manufacturing or beaten back China’s attempts to take the lead in semiconductors, but they look on track to accomplish those goals. If, two years ago, we had predicted what success for these policies would look like as of 2024, this is what we would have predicted.

These successes deserve a lot more attention, and a lot more credit, than they have so far been given.

Also notice that so far, there’s not much investment in electric car manufacturing in the U.S., despite a steady increase in electric car sales. This is probably because American car companies are largely repurposing existing factory lines to make EVs instead of internal combustion cars, which is fairly cheap to do. The big new thing you have to build is battery factories.

Very good post. I especially like the points about government prompting, working the kinks out of new industrial policies, and the impact on Chinese industry.

One question, though, re: "Barack Obama never seemed to recognize how big of a deal this was." Didn't Obama try to pivot to Asia (i.e., against China) from the start, shifting military assets into the region, building anti-China alliances, the TPP, etc? Some of Biden's anti-China policy drew on this, no?

This is a wonderful post! This is exactly why I subscribe to Noah's blog. Without something like this, I would have no way of knowing if Biden's industrial strategy was working or not. This makes me feel better about our trajectory. I can only hope that if Harris wins she will continue with this strategy and maybe even double down on it. The only thing that should also be mentioned is that one of the reasons tariffs and "buy American" provisions in the legislation are important is to prevent leakage of the benefits of the funding to China.