Book Review: "Freedom's Forge"

How we handled the War Economy a century ago.

I’ve been doing a series of posts on what I call the “War Economy” — how the U.S. will have to transform its economy as a result of geopolitical conflict. A friend suggested that I read a book called Freedom's Forge: How American Business Produced Victory in World War II, by Arthur Herman. I had read a couple of books about U.S. war mobilization in WW2, but my friend did not lead me astray — this one turned out to be my favorite so far.

Freedom’s Forge, published in 2012, tells the story of war production from the perspective of two American industrialists — William S. Knudsen and Henry J. Kaiser. Herman gives Knudsen more attention, which makes sense because has the far more compelling personal story — a poor Danish immigrant who worked his way up from the factory floor, discovered a genius for mass production, and ended up building GM’s Chevrolet division to be even bigger than Ford. When the Roosevelt administration decided to start producing materiel en masse to help Britain fend off the Nazis in 1940 (and to prepare for eventual direct entry into the war), they called up Knudsen to help them get things going. Motivated by his desire to defend the freedom he had found in his adopted land, Knudsen served on an early body called the National Defense Advisory Commission, and later served as the chairman of the Office of Production Management.

Knudsen loved America, and he also loved big business. He had seen first-hand the amazing feats of which private-sector mass production was capable, and he believed that the government should harness this incredible power by simply paying big business to make everything that the military needed. That’s pretty close to what ended up actually happening, but Knudsen eventually got pushed out of OPM — which got reorganized as the War Production Board — in part because New Dealers saw him as too friendly to business as an institution. Instead he received a commission as a general and ended up working as a free-floating consultant for the government, flying around and troubleshooting problems with mass production.

But the basic division of labor between government and business that Knudsen helped develop in those early years lived on. The government decided what would be produced, paid for it, and ensured the availability of the basic materials needed (through rationing and other means). Private business did all of the actual building, including designing weapons, creating the factories to build those weapons, operating those factories, hiring labor, ordering the correct machine tools, and arranging supply chains and subcontracting.

Freedom’s Forge is at its best when it describes, in loving and nerdy detail, how this production chain worked. And work it did — the U.S. managed to out-produce the rest of the Allies combined, while devoting a much smaller portion of its economy to the military than other nations, and even increasing civilian consumption by the war’s end.

Government and business were symbiotic in this process; each institution had its part to play, and it played it well. U.S. companies had had lots of experience producing vast amounts of cars, airplanes, etc. during the big economic boom of the 1920s, while the New Deal bureaucracies had gotten some practice taxing and spending and allocating economic resources to fight the Depression. Thus it was natural to break things down the way Knudsen and the other early members of the NDAC and OPM envisioned.

But what’s interesting is that this division of labor didn’t develop harmoniously and smoothly — there was plenty of jostling between business and government, with Knudsen’s firing being only one small example. Herman relates a case in which Roosevelt’s Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes made a giant list of 70,000 individual cases where Henry Kaiser’s companies had violated labor law. Kaiser simply threatened a publicity campaign against the administration, and Ickes backed off. There are various other examples in the book.

Unions got involved too. There were massive waves of strikes all throughout the war production period. The Roosevelt administration, though initially supportive, eventually had to crack down. But that display of union strength, at a critical time, helped to cement labor’s power and pave the way for the good manufacturing jobs that Americans remember from the postwar boom years (whether that power and those wages were sustainable is another question).

If there’s one weakness of Freedom’s Forge, it’s that Herman clearly takes a side in these conflicts. The author trumpets the achievements of the heroic industrialists, but scoffs at the meddlesome New Dealers, implies that the CIO initiated many of its strikes as a way of subverting the U.S. in the name of communism, and flat-out dismisses Keynesian macroeconomics. It’s possible to see this as a response or a corrective to other historians who make the opposite attribution, crediting government planning while minimizing the contributions of business. But read in isolation, it’s just too one-sided. Without government to put up the cash, the war production never would have happened at all. Government also paid for much of the critical infrastructure the companies used to transport materials for production. Ultimately, government mediation was instrumental in putting a stop to the waves of strikes that Herman decries.

By taking sides in the turf wars between government, business, and labor during WW2, Herman misses the bigger picture of how the war shaped U.S. institutional development. The first Gilded Age and the subsequent Depression didn’t really define the roles the country’s economic institutions — instead, it was a bitter, chaotic, sometimes violent free-for-all. The overriding imperative of WW2 forced business, government, and labor to cooperate for the first time, and proved that such cooperation could achieve incredible feats of production. The minor jostling that Herman documents was ultimately benign — a process of U.S. institutions working out their core competencies.

The big question looming over Freedom’s Forge, as I read it in 2022, is whether the basic division of responsibilities worked out in WW2 still makes sense in the present day. Technology has become far more sophisticated, so that often there is only one company that produces a critical piece of military equipment — Elon Musk’s Starlink being the most vivid example. During the Lend-Lease years, when Bill Knudsen went to Henry Ford and asked him to help build weapons, Ford refused, declaring that supporting Britain’s effort to defend itself against the Nazis would be encouraging war, and encouraging America’s entanglement in war. The two men had a shouting match. But in the end, Knudsen was able to go to other car companies, because there were other car companies to go to. And eventually, shamed and threatened by that competition — and by the outbreak of wider war — Ford chose to join in. In an age where companies control proprietary, unique, indispensable military technologies, simply using competition as a check on individual industrialists’ recalcitrance may not be as effective.

Another looming question is how international supply chains complicate the picture. Herman describes in detail how big companies like GM and Boeing were hyper-efficient in part because they outsourced a lot of key tasks to a huge host of smaller companies. But because the world wasn’t very globalized, those smaller subcontracting companies were almost all in America. In today’s globalized world, many of the crucial suppliers are in China. Those will not be available during a war with China, and export controls, tariffs, and security concerns are making them less available in the current Cold War-like environment.

The U.S. is simply not the manufacturing powerhouse we were in 1940 — the workshop of the world, where anything could be made for the right price. China is that now. So our task may be harder this time around, and may involve more central planning.

The pandemic, however, provides some reasons to think that the American system whose creation is described in Freedom’s Forge is still basically intact. Though we had difficulty manufacturing simpler items like masks and ventilators in the early days — due to pre-pandemic offshoring of suppliers — we eventually ramped up. N95 mask production went from 45 million a month in January 2020 to 180 million a month by the end of the year. And when it came to vaccines, the U.S. effort was even more prodigious, smoothly and quickly producing enough mRNA vaccine doses to immunize every American who wanted a shot, even as China struggled to do the same.

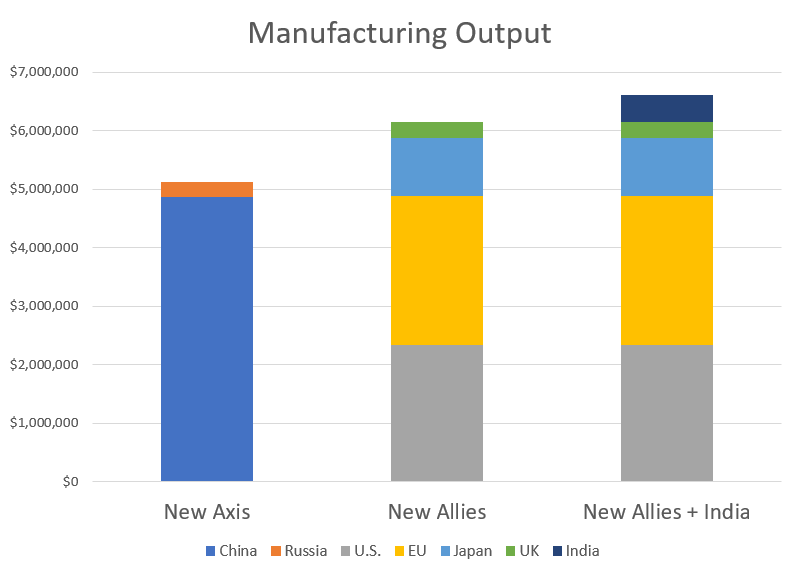

So the U.S. still has some of the old Bill Knudsen magic left. But if we do have a protracted standoff or a hot war with China, our system will be sorely tested. In order for the U.S. and its allies to match China’s output, we will need to coordinate not just within our borders, but whole production chains that stretch from Asia to North America to Europe.

In other words, a successful sequel to Freedom’s Forge will have to include less offshoring of supply chains to China, but more supply chains between U.S. allies. Rhetorically and conceptually, that could be a tough needle to thread.

At the same time, the U.S. is just now beginning to emerge from its Second Gilded Age — a time when government and business no longer considered themselves natural partners, and when “private vs. public” thinking dominated many of our intellectual debates. As in WW2, we will have to learn — or re-learn — how those institutions can complement each other instead of thinking of themselves as competitors. And we will have to do that quickly, even as we navigate the new complexities of advanced technology and globalization.

We sure could use a few people like Bill Knudsen right now.

Thanks Noah. I'm Big Bill Knudsen's great-grandson and it's terrific seeing the story put in front of a new audience. His choice to become a dollar a year man and work for FDR made him no friends at GM, but there was no way he could say no when asked by the president to serve. It's a tough legacy to live up to. I'd add that there was more than one time that he and Henry Ford got into a shouting match.

Good review Noah, I will have to add this book to my list. I might also recommend a very good book by Victor Davis Hanson called “The Second World Wars.”

One oft-overlooked aspect of WW2 was how the Allies worked in concert with each other. They shared technology and tactics in ways that the Axis never did. As a few examples:

(1) The US used navalized B-24s and escort carriers quite effectively with Commonwealth convoy methods and anti-submarine technology to win the Battle of the Atlantic. By late 1943, U-boat service was a death sentence to their crews.

(2) The US and Commonwealth forces timed the Normandy landings in coordination with the Soviets who near simultaneously launched Operation Bagration which caused a general collapse of Axis Europe in less than a year.

(3) The US and Commonwealth collaborated very closely on tanks, aircraft and naval technology as well as military training methods. Some good examples are the Americans’ use of Rolls Royce engines in P-51 mustangs. Or the US use of a British design for tank landing ships. The British use of American amphibious landing craft. The Manhattan Project, etc...Another example is the US training and equipping of Chinese Nationalist forces to fight the Japanese.

The Allies were very good at Combined/Allied operations.