At least five interesting things to start your week (#42)

The end of Chevron deference; export controls; jerky American profs; basic income; economics of AI; solar power uses; Global South tariffs; Gen Z wages; Stiglitz

OK, so this post really stretches the “at least five interesting things” concept. Technically, nine is “at least five”!

First, podcasts. Here’s an episode of Econ 102. Most of it is a typical Q&A episode, except in the last 15 or 20 minutes, Erik makes me talk about romantic relationships, and even give relationship advice. Listen at your own peril:

I also went on the Bankless podcast with Vitalik Buterin to talk about my post about why authoritarianism might prevail over liberalism in the age of the internet. Vitalik liked my theory but was pretty bullish that liberalism will overcome these obstacles:

OK, on to this week’s list of…nine interesting things! If you make it all the way to the end you get a prize.1

1. Lawyers are your regulators now

I’m going to write more at some point about the Supreme Court decision reversing the famous “Chevron deference” doctrine. For now, I just want to make one point about it, which is about the balance of power between the bureaucracy and the courts.

Basically, laws are usually ambiguous in some way. “Chevron deference” meant that when they have to adjudicate one of the ambiguous parts of a regulatory law, U.S. courts had to defer to the regulators’ interpretation of the ambiguous part. Now they don’t have to defer. So a lot of the burden of legal interpretation just shifted from the bureaucrats to the courts. Chief Justice John Roberts basically summed up SCOTUS’ thinking when he said “Chevron’s presumption is misguided because agencies have no special competence in resolving statutory ambiguities. Courts do.”

A lot of people in the private sector are hailing this as a fundamentally deregulatory move. In some cases that may be true — for example, Austen Allred describes his experience being given the runaround by civil servants who refused to explain their interpretations of the law. But in many cases, what seems likely to happen is that courts are going to have to adjudicate the minutiae of laws without really having the personnel to do so.

Andy Fois, chair of the Administrative Conference of the United States — the branch of the federal bureaucracy whose job it is to make the bureaucracy more efficient — notes that although this could result in regulators simply backing off and not trying to stop businesses from doing things, it also could easily result in increased workloads for the courts. Basically, if a regulatory agency sues to stop a business from doing something, it’s now the court’s job to figure out exactly what the law allows. This could take a long time, because courts don’t really have the personnel or the expertise to adjudicate complex technical matters.

In other words, there seems to be a possibility that the new doctrine may end up working a bit like the dreaded NEPA and CEQA, except with regulators suing businesses instead of NIMBYs. If regulators want to stop businesses from doing something, their best bet for doing that might now be to just sue and tie up the business for years and years in court. That’s…not the ideal way to do regulation.

Businesspeople who dislike the bureaucracy may now come to remember why they also dislike lawyers.

As Brendan Carr of the FCC points out, this change won’t apply to “questions of major economic and political significance”, which were already not covered under Chevron deference. So it’s possible that this change won’t actually be that impactful. It’s even possible that courts will continue to defer to regulatory agencies’ interpretations out of convenience, even if it’s not legally required.

But one thing seems certain — the end of Chevron deference puts more of a burden on Congress to write very hyper-specific laws. This seems likely to balloon the length of legislation that has already grown almost incomprehensibly long. So that’s bullish for companies that offer generative AI solutions for writing and reading laws.

In any case, the end of Chevron is yet another example how the U.S. slapped together the functionality of a modern state in the 20th century through a series of court decisions, without making the deep and thorough revisions to the Constitution that are really needed to deal with modern economic, social, and technological problems. For a while, we simply pretended that the system we set up in the 1800s to deal with the problems of pre-industrial society had always been set up to deal with the problems of industrial society. Now, thanks to the new conservative SCOTUS, we can no longer pretend. We will either have to revise our system, or live with 19th-century institutions.

2. Export controls are having a big effect on China’s chip industry

When the U.S. imposed export controls on China’s semiconductor industry, a lot of people thought the controls weren’t going to work. Some semiconductor experts like Dylan Patel thought the controls were way too porous and weak to have the desired effect. Meanwhile, China boosters claimed that the controls would simply spur China to develop its own indigenous chipmaking industry instead of continuing to depend on the West. (This latter argument never made a lot of sense to me, since China was already trying very hard to indigenize its chip industry, but whatever.)

When Huawei came out with a 7nm chip in late 2023, many hailed it as a sign that export controls had failed. Recall that U.S. export controls were designed to make it a lot harder for China to make anything smaller than 14nm. This was followed closely by Huawei announcing that it was testing a way to make 5nm chips — very close to the best that Intel can make — using older equipment not covered by the initial round of export controls. To China boosters, at least, the collapse and failure of U.S. export controls seemed complete.

But in fact, the export controls have quietly been having a significant effect. Huawei’s Ascend 910B chip, an AI-training chip that the company claimed was a rival to Nvidia’s, uses a 7nm process. And according to new reports, fully 80% of the Ascend 910Bs are defective, and China’s foundry SMIC is having trouble making them in large volumes:

Previously, Huawei claimed its second-generation AI chip “Ascend 910B” could compete with NVIDIA’s A100 and was working to replace NVIDIA, which holds over 90% of the market share in China. However, Huawei is now facing significant obstacles in expanding its production capacity. According to a report from ChosunBiz, the chip is being manufactured by China’s leading semiconductor foundry, SMIC, and has been in mass production for over half a year, yet the yield rate remains around 20%. Frequent equipment failures have severely limited production capacity.

The report on June 27 states that despite being in mass production for over half a year, SMIC’s manufacturing of the Ascend 910B is still facing challenges, as four out of five chips still have defects. Meanwhile, due to increased U.S. export restrictions, the supply of equipment parts has been disrupted, causing production output to fall far short of targets.

SMIC initially projected an annual production of 500,000 units for the Ascend 910B, but due to continuous equipment failures, this goal has not been met. Currently, SMIC is unable to introduce new equipment and has to retrofit low-performance Deep Ultraviolet (DUV) equipment to replace advanced Extreme Ultraviolet (EUV) equipment for etching the 7nm circuits of the AI chips.

Recall that the Kirin 9000S, Huawei’s famous “sanction-busting” phone processor chip, that is also made on a 7nm process by SMIC. This raises the question of whether that chip will face similar production problems.

This is exactly how export controls were supposed to work! They were not supposed to immediately shut off China’s ability to make advances in semiconductors; instead, they were supposed to erode the country’s competitiveness, slow it down, and keep it a step behind. So far, it looks like export controls are succeeding at that goal.

Meanwhile, Huawei appears to be pessimistic about its chances of making even small batches of even better chips:

A high-ranking Huawei executive has reportedly made a rare admission that China’s ambitious semiconductor efforts may have peaked. On June 9, during the Mobile Computility Network Conference in Suzhou, China, Huawei’s Cloud Services CEO Zhang Ping’an voiced concerns about China’s inability to source 3.5nm chips because of U.S. sanctions.

Given the difficulties China is facing from U.S. sanctions, Zhang believes Huawei and other manufacturers should make more effective use of the technology that is available. He said, "The reality is that we can't introduce advanced manufacturing equipment due to U.S. sanctions, and we need to find ways to effectively utilize the 7nm semiconductors."

So while analysts like Patel may be right that the controls could use some tightening, even the controls as they exist today are having a major effect on slowing down China’s all-important chip industry.

Of course, this may soon be academic, since Trump seems likely to return to the presidency soon, and China will likely find some way to bribe, bully, or otherwise persuade him to drop or significantly weaken the export controls, much as it got him to flip-flop on TikTok. But for a brief moment, the Biden administration really was beating the Chinese manufacturing machine.

3. Why are American academics such jerks on Twitter?

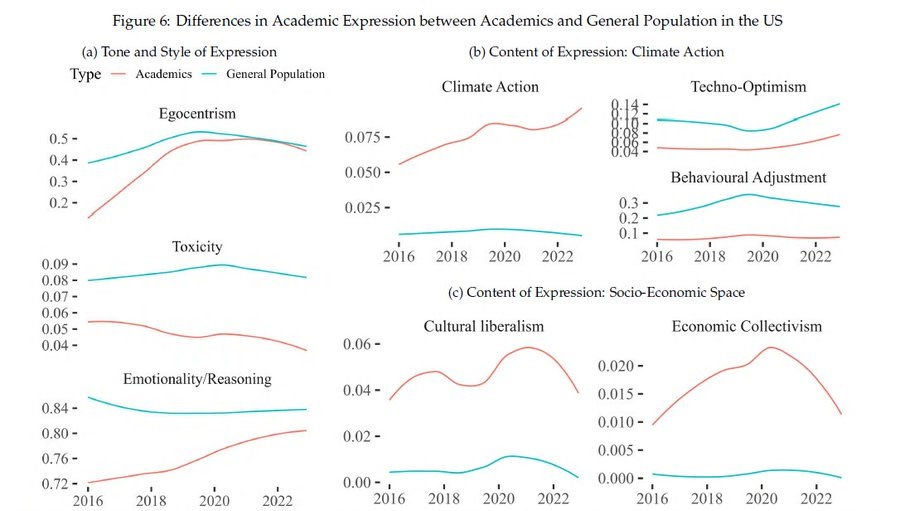

Prashant Garg and Thiemo Fetzer have a fun new paper, about academics who post on Twitter. Here’s a thread where Garg summarizes the results. In general, academics are kind of what you’d expect — more rational, less toxic, less egocentric, more socialist, more culturally liberal, and more concerned about climate change than the general public:

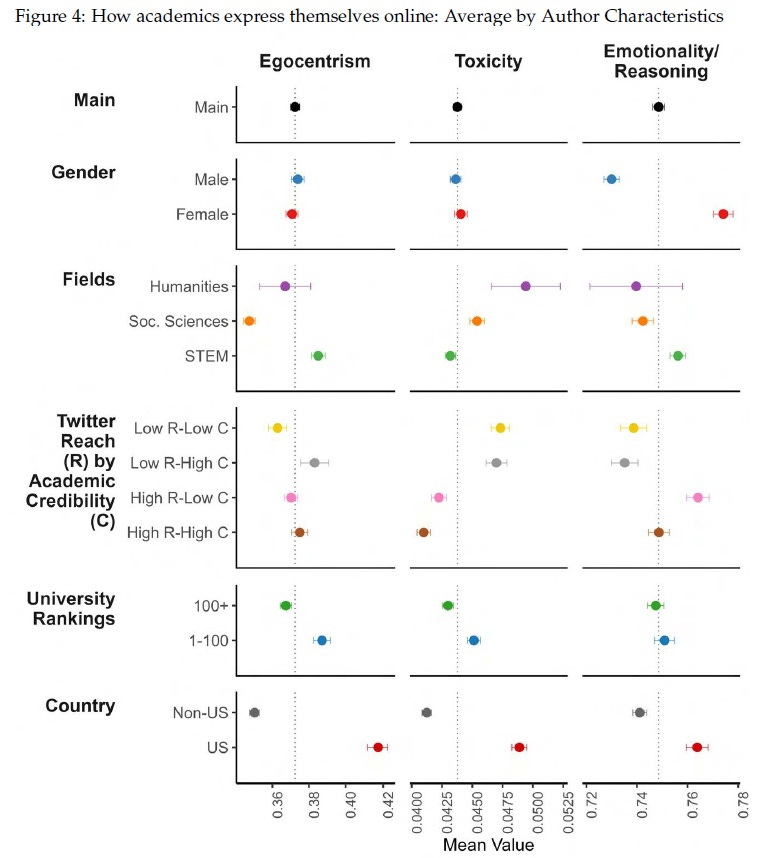

But this is for all academics, including those from other countries. American academics are a little bit different than others. They’re significantly more egocentric, toxic, and emotional:

Why are American academics worse? No obvious explanation leaps out from the other variables here. Academics at top-ranked universities are a little more egocentric than others, but that’s only to be expected. Humanities academics are a bit more toxic and a bit less egocentric than STEM academics; I’m not sure what that tells us.

I see three potential explanations here. The first is elite overproduction — the U.S. pumps out new PhDs at industrial scale, but its shrinking university sector can only employ a few of them. That gives American academics a reason to be toxic, and it also creates an incentive to be egocentric — even for the people who end up winning the competition and landing the plum jobs.

The second is the activist drift of academia. Steve Teles has a great essay detailing how some academic fields have started emphasizing activism as an essential component of a professor’s job. This is certainly consistent with some of what we’ve seen from the history and sociology fields in recent years.

The third likely explanation is just social unrest. America entered a particularly turbulent time of social unrest in the mid-2010s, and that’s going to tend to make everyone a little more shouty and toxic.

Of course, it’s possible that all three of these factors could interact. Activist academics are more likely to respond to a time of unrest by going out and shouting on social media, and the crappy job market probably just stresses them out even more. In any case, this is one more piece of evidence that something has gone wrong in the culture of U.S. academia.

4. Basic income is good, but don’t expect too much of it

One of the best new ideas of the 2010s was that unconditional cash benefits are a good form of welfare. Basically, mailing people checks and then letting them decide what to do with it is preferable to America’s usual thicket of work requirements and targeted subsidies. This

The most extreme form of this idea is Universal Basic Income. True UBI is a political nonstarter, due to the enormous expense involved, but many people have gotten interested in more modest versions of the idea — for example, giving everyone $1000 a month. Some people have become testing this in the real world — one example is the Denver Basic Income Project, which randomly gave $1000 a month to homeless people (either monthly or as a lump sum) and observed the results.

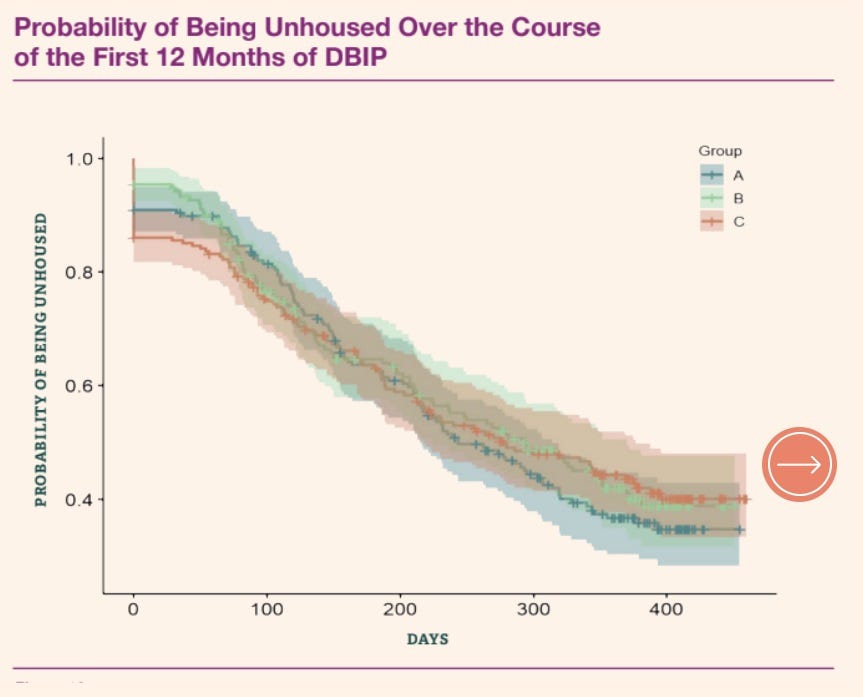

The obvious hope was that $1000 a month would lead to fewer homeless people, but that…did not happen. Here’s a comparison of homelessness levels between the $1000-a-month group and a control group that only got $50 a month:

Homelessness goes down a lot for both groups of the course of the study, since most spells of homelessness are short-term and temporary. But the difference between the groups is clearly not statistically significant. There might be a small effect here, but it’s too small to detect with this sample size.

This is a bit disappointing, but not very surprising. If I were homeless, I would not move into a new place based on a temporary income boost that I knew would end in 12 months; instead, I’d use the money for more immediate concerns like food and medical bills. This appears to be what the study subjects did, which is consistent with other evidence about the usefulness of cash benefits.

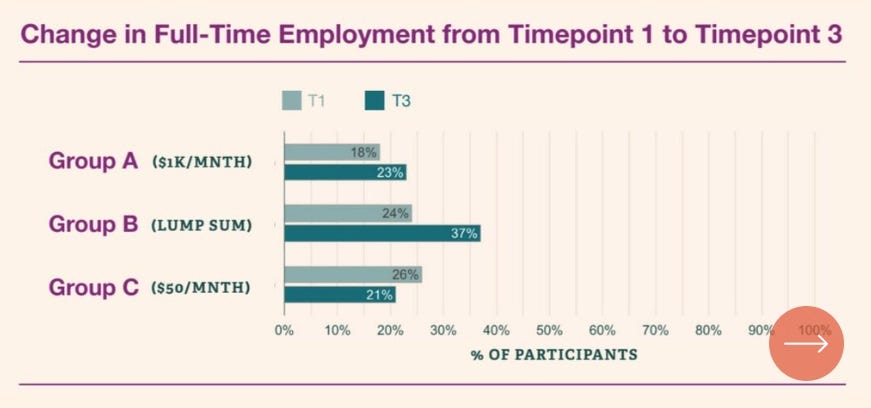

Which is fine! Using free cash to pay bills doesn’t just help people survive in the short term — it also frees them up to improve their lives for the long term. Although the DBIP people apparently didn’t do a formal test to see if the difference was significant, it does look like the groups who got $12,000 in free money were more likely to be employed full-time than the groups that only got $600 in free money:

So while we shouldn’t expect an infusion of cash to solve the homelessness problem, it can help solve lots of long-term problems and get poor people on their feet. And if the benefits were more permanent, who knows — it might even move the needle on homelessness too. (Though in the end, building more supply is a necessary part of any solution to homelessness.)

I think the lesson here is: Don’t expect too much of basic income. It’s good, but it doesn’t magically solve every problem people have.

5. Acemoglu and the macroeconomics of AI

Daron Acemoglu, who is probably the most prestigious and accomplished economist in his prime today, does not like AI. He wrote a whole book about how the development of technologies like AI needs to be regulated to stop them from causing mass unemployment and inequality. I did not like that book at all.

But what’s interesting is that Acemoglu thinks that AI will immiserate human workers without actually boosting economic growth very much if at all. Usually these arguments are framed in terms of “growth vs. inequality”. But Acemoglu thinks AI will increase inequality without improving growth much! He makes this argument in his book, but he also has a new paper making the argument more formally:

So long as AI’s microeconomic effects are driven by cost savings/productivity improvements at the task level, its macroeconomic consequencescan be estimated by what fraction of tasks are impacted and average task-level cost savings. Using existing estimates on exposure to AI and productivity improvements at the task level, these macroeconomic effects appear nontrivial but modest—no more than a 0.66% increase in total factor productivity (TFP) over 10 years. The paper then argues that even these estimates could be exaggerated, because early evidence is from easy-to-learn tasks, whereas some of the future effects will come from hard-to-learn tasks, where there are many context-dependent factors affecting decision-making and no objective outcome measures from which to learn successful performance. Consequently, predicted TFP gains over the next 10 years are even more modest and are predicted to be less than 0.53%. I also explore AI’s wage and inequality effects. I show theoretically that even when AI improves the productivity of low-skill workers in certain tasks (without creating new tasks for them), this may increase rather than reduce inequality.

I was going to write a critique of this paper, but Maxwell Tabarrok beat me to it:

Tabarrok points out the big problem with this paper, which is that Acemoglu only got the results he did by arbitrarily turning off half of his model. Acemoglu assumes that AI can do four things:

Replace labor at existing tasks

Make labor more productive at existing tasks

Make capital more productive

Create new tasks for workers to do

As Tabarrok notes, Acemoglu arrives at his result in this paper simply by assuming that #3 and #4 don’t happen at all:

“Deepening automation” in Acemoglu’s model means increasing the efficiency of tasks already performed by machines…AI might deepen automation by creating new algorithms that improve Google’s search results on a fixed compute budget or replacing expensive quality control machinery with vision-based machine learning, for example.

This kind of productivity improvement can have huge growth effects. The second industrial revolution was mostly “deepening automation” growth. Electricity, machine tools, and Bessemer steel improved already automated processes, leading to the fastest rate of economic growth the US has ever seen. In addition, this deepening automation always increase wages in Acemoglu’s model, in contrast to the possibility of negative wage effects from the extensive margin automation that he focuses on…Transformers are already being used to train robots, operate self driving cars, and improve credit card fraud detection. All examples of increasing the productivity of tasks already performed by machines…

Potential economic gains from new tasks aren’t included in Acemoglu’s headline estimation of AI’s productivity impact either. This is strange since he has written a previous paper studying the creation of new tasks and their growth implications in the exact same model…He doesn’t end up including gains or losses from new tasks in his final count of productivity effects, but this process of ignoring possible gains from new good tasks and making large empirical assumptions to get a negative effect from new bad tasks exemplifies a pattern of motivated reasoning that is repeated throughout the paper.

Tabarrok also points out that Acemoglu gives essentially no justification for assuming away these important pieces of his own model.

This demonstrates how macroeconomic theorists can basically arrive at any conclusion they want by choosing which assumptions to make. Acemoglu wanted to write a paper where AI increases inequality without improving economic growth much, so he simply ignored the parts of his own theory that show how AI could do the opposite.

I don’t think we should regard the results of that sort of exercise as a credible guide to policy.

6. Casey Handmer on the solar revolution

I’ve been touting solar power as part of a technological revolution that will transform the world. But what will we do with all that cheap power? I can think of some ideas off the top of my head, the most obvious being A) do the stuff we do now, but more cheaply, and B) use it for AI and crypto. But Casey Handmer has thought long and hard about this topic, and he has an excellent blog post with a list of suggestions for what to do with ultra-cheap solar. Some of these are a lot more realistic than others, but the whole list is worth reading in full. Some excerpts:

Solar desalination….For less than one cent on the dollar, we can build our own artificial rivers to safeguard our food supply and reduce stress on river ecosystems, all while reducing cost and complexity of legacy irrigation infrastructure. Many people are saying this. In the case of Southern California, we can double our supply from the Colorado, build a global-scale light metal processing industry, and fix the Salton Sea for just $5b/year over 10 years, and that’s without any further improvements in technology or cost…

Environmental and ecological restoration…Why stop at the Salton Sea? A whole bunch of intractable ecological problems, unsolvable in a condition of energy scarcity, can be solved as a byproduct of newly scaled solar PV-based industries. In California, we can restore the Owens Lake and Owens Valley to its pre-scarcity water abundance. We can use the dams on the lower Colorado to enable more irrigation further upstream, including in Arizona and Nevada…

Synthetic fuels…Solar green hydrogen’s largest use case is the catalytic reduction of atmospheric CO2 to produce synthetic hydrocarbon fuel – oil and gas from sunlight and air. Solar synthetic hydrocarbons are poised to undercut drilling as the cheapest source of chemical energy for humanity, while solar is already cheaper energy in the form of electricity and heat. Despite the transformational economic effects of retrofitting the entire supply side of the global hydrocarbon supply chain over the next two decades, relatively few companies, including my own Terraform Industries, Rivan, General Galactic, and Turn2X are aggressively accelerating toward this goal…Synthetic fuels are the only way to increase oil supply, cut prices, and slash strategic and security supply chain issues…

Fertilizer…[S]olar green hydrogen undercuts methane, creating opportunities to disrupt legacy fertilizer plants with new, solar powered, modular plants that operate in a solar array. It is also possible to produce nitrate via a direct electric process, such as that being developed by Nitricity…

Mining…[W]e can melt arbitrary rocks and electrocatalytically fractionally separate them into each of their constituent metals plus oxygen which, like synthetic fuels, is vented as a byproduct. This approach, which is ludicrously profligate in its use of power, enables the processing of much poorer ores into metals…[T]here are dozens of electrocatalytic refining techniques in active development, such as the copper process being developed by Still Bright.

A key point here is that a world of abundant cheap solar energy quickly becomes a world of abundant minerals, liquid fuels, fertilizers, and the other physical feedstocks of industrial civilization. Energy really is at the root of everything, and for the first time, we’ve discovered a way to produce electrical energy more cheaply than by burning coal and natural gas. This is going to change the world.

7. Tariffs on Chinese goods spread to the Global South

One thing a lot of people (including myself) have been predicting about Biden’s tariffs on China was that they would start a cascade. Basically, once Chinese EVs and other products are shut out of the U.S., Chinese producers will go looking for other places to sell them. Those places will face an even greater surge of Chinese imports than before, putting even more competitive pressure on their domestic industries. That will motivate some of those countries to erect their own trade barriers against Chinese products, which will force the vast flood of exports onto an even smaller set of countries, and so on.

It looks like this prediction is coming true, and rather quickly. Indonesia just decided to slap huge tariffs on Chinese imports:

Indonesia will soon impose up to a 200-per cent import tariff on Chinese goods to mitigate the effects of the ongoing trade war between China and the United States…Indonesia’s Trade Minister Zulkifli Hasan…explained that the trade war is causing an oversupply in China as their products face rejection by Western countries, forcing them to redirect exports to other markets like Indonesia.

Tariffs for Chinese-made products would range from 100 to 200 per cent, Hasan noted…“The United States can impose a 200-per cent tariff on imported ceramics or clothes; we can do it as well to ensure our MSMEs and industries will survive and thrive,” he remarked.

This follows on the heels of India, Mexico, Brazil, and others. The Global South — if such a thing can be said to exist — is vigorously and actively putting up walls against the great Chinese export flood.

The question now becomes: Where will the Chinese exports end up going? Some of them will go nowhere, of course, exacerbating China’s domestic capacity and putting downward pressure on Chinese domestic prices and profits. But my intuition is that Europe will end up buying a lot of this stuff. Europe’s tariffs on Chinese EVs were far lower than Indonesia’s or the U.S., with a maximum rate of only 38%, and were applied to a much narrower range of goods. In general, the rich consumer markets of Europe are still wide open to the new flood of Chinese exports, and European manufacturers must be sweating.

8. Young Americans’ wages are higher than their parents’ were

The Economic Innovation Group — a great little think tank that often flies under the radar — has a cool new report about the state of American workers. There’s lots in there to read, but I just thought I should flag some results about the young generation. Compared to older generations, the Zoomers’ wages are…well, they’re really zooming!

The effect holds for both young men and young women equally.

Note that both Millennial and Gen X workers initially did no better than older generations, and started to pull away only after age 25 or so. That’s probably due to A) a selection effect from high-earning workers staying in school until their late 20s, and B) the Great Recession. But Zoomers are earning much more than Millennials or Gen Xers right out of the gate. And thanks to the good economy since 2013 or so, even the unlucky Millennials are now doing solidly better than older generations.

This should help to debunk the popular narrative that young Americans are falling behind earlier generations. We’ve had a strong economy and a strong labor market for a decade now, and the effects are really adding up.

9. Joe Stiglitz makes a very basic mistake on density

Tyler Cowen is among the best interviewers in the business, and his “Conversations with Tyler” series is always worth reading (or watching, or listening or whatever you people do). His recent interview with the legendary economist Joe Stiglitz is no exception. Much of what Stiglitz says is sensible. For example, Stiglitz is one of the intellectual pioneers of modern Georgism, and he makes a great argument for taxing the value of land:

COWEN: What is it you think of Henry George and George’s economics today?

STIGLITZ: Well, that was another set of articles that I wrote in the late ’70s concerning the land rents associated with the cities…I developed a whole theory of the rents that would arise in that kind of context, as people facing costly transportation would bid up the price of land…Then I asked the question, what is the relationship between the optimal size of the city, the optimal spending on public goods by the city, and the rents that were generated in the way I just described? There was a remarkable theorem that came out, which was that if you have optimal-size cities and you tax the rents 100 percent, that would be exactly the right amount to finance the optimal amount of public goods.

It was a very theoretical idea, but it captured an important idea that Henry George, who was one of the great economists of the 19th century, had enunciated, which was, taxing land rents was the most efficient way for raising revenues.

COWEN: Is that true today? For a given level of taxation, do you think we should take more of it from landlords?

STIGLITZ: Yes, I think the ownership of land still provides one of the most important bases of taxation, and we almost surely do not tax it as much as we should. When the government, say, in New York City, builds a subway, those near the subway have an enormous increase windfall gain from the value of their land. You can actually document the land goes up. The city is paying, all the citizens are paying for it, and yet the owners of the land get a windfall.

But then when Tyler asks Stiglitz about allowing denser housing construction — something he hasn’t personally done a lot of research on — Stiglitz runs completely off the rails:

COWEN: Do you favor the deregulations of the current YIMBY movement — allow a lot more building?

STIGLITZ: No. That goes actually to one of the themes of my book. One of the themes in my book is, one person’s freedom is another person’s unfreedom. That means that what I can do . . . I talk about freedom as what somebody could do, his opportunity set, his choices that he could make. And when one person exerts an externality on another by exerting his freedom, he’s constraining the freedom of others.

If you have unfettered building — for instance, you don’t have any zoning — you can have a building as high as you want. The problem is that your high building deprives another building of light. There may be noise. You don’t want your children exposed to, say, a brothel that is created next door. In the book, I actually talk about one example. Houston is a city with relatively little zoning, and I have some quotes from people living there, describing some of the challenges that that results in.

This is nonsense, for reasons that economist Nathan Goodman explains on Twitter. Yes, of course housing creates negative externalities — crowding, darkness, etc. But it creates plenty of positive externalities too — urban density makes cities more productive, makes it more economical to build efficient mass transit, eases pressure on the environment, and so on.

Both the positive and negative externalities of density have been mostly known since the days of Alfred Marshall, who wrote about them in 1890. If density didn’t have positive externalities, cities wouldn’t even exist in the first place — everyone would just live out in the country. Stiglitz should know about this, but instead he just ignores all the positive externalities and pretends like density brings only harm. It’s sad to see a great economist — even one who’s 81 years old — make such a basic mistake.

The prize is the satisfaction of having spent extra minutes of your life reading economics blogs, which is of course the most valuable and enlightening thing you can do with your time.

My prediction: the end of Chevron deference will result in an absolute flood of case filings in federal courts. If businesses can gain approximately $150 in benefits gained/burdens and taxes avoided for every dollar spent lobbying Congress, think how much they can gain by filing anti-regulatory lawsuits. Unfortunately, I do not have a link for that $150 figure. I read it some years ago and do not remember where.

Here's the real problem: poor people don't have the money to pay for lobbyists or lawsuits.

Loved the section on solar. Don't stop an Owens Lake, fill Mono!