At least five interesting things for the middle of your week (#22)

Test score collapse, triumph of the vibes, U.S. dependence on China, the benefits of upzoning, immigrants and jobs, and a world at war

I hope you’re enjoying these roundups; the lack of a punchy headline always means they go a bit less viral than my regular posts, but I still love doing them. I’m pretty behind on all the interesting things I want to comment on.

This week we have a special episode of Econ 102 — a crossover with the hosts of the new Age of Miracles podcast, Packy McCormick of Not Boring and Julia DeWahl of Antares! In this episode, we debate the future of energy production — solar vs. nuclear vs. fusion.

And here are links on Apple Podcasts and YouTube.

Anyway, on to this week’s roundup of interesting things! This week, again, there are six instead of five.

1. The collapse of global test scores (it’s probably the phones)

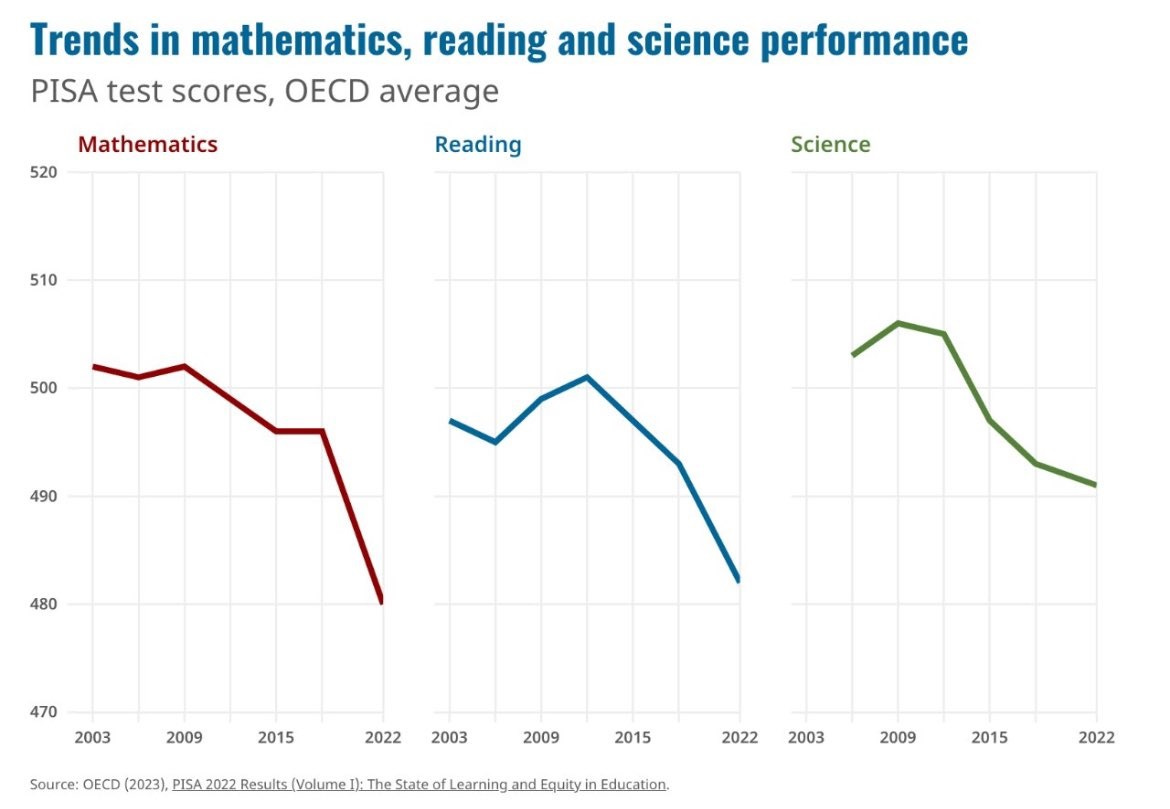

In my last roundup, I pointed out that American kids actually do pretty well on global test scores, except in math. But that’s a relative measure. In fact, test scores have been falling all over the developed world since around 2010:

The U.S.’ good relative performance is partly because we’ve fallen a little less than other countries. In general, students are just not doing well, all over the globe.

Why? When you see an international trend like this, you should automatically be suspicious of political or institutional explanations, because those are country-specific. Woke politics or education funding cuts or whatever are highly unlikely to explain a trend this broad. Instead, we should look at technological trends, since in the absence of a world war, technology is the main thing that affects the whole developed world more or less simultaneously.

The timing of the dropoff makes it pretty clear what the chief suspect is here: Smartphones. There are actually a lot of studies measuring the impact of smartphones on student learning, and the consensus is that it’s bad. This is from a meta-analysis by Sunday et al. (2021):

[T]he overarching goal of this meta-analysis was to comprehensively synthesize existing research to investigate the effects of smartphone addiction on learning. The authors included 44 studies…in the analysis yielding a sample size of N = 147,943 college students from 16 countries. The results show that smartphone addiction negatively impacts students' learning and overall academic performance…Further, findings suggest that the greater the use of a phone while studying, the greater the negative impact on learning and academic achievement. Additionally, the results suggest that skills and cognitive abilities needed for students’ academic success and learning are negatively impacted.

That’s pretty unambiguous. And it’s not like these are just correlations, either; it’s very easy to do a controlled experiment on smartphone use in the classroom. And when you do, you find that kids without phones in the classroom learn better.

Now, this doesn’t mean smartphones are bad for learning overall; outside of the classroom, they can have major benefits, such as making it easier for kids to look things up online or ask help from friends. But inside the classroom, smartphones are a distraction that impedes learning. The clear solution is simply to ban phones from schools, as many are now proposing. This might have the added benefit of making kids feel less stressed throughout their day.

Remember, technology ultimately gives humans more power over our world, but it takes time for us to learn how to use it appropriately. And it seems like smartphones in the classroom are just not an appropriate use of that technology.

2. Will Stancil is winning the debate about the economy

If you haven’t been following the saga of Will Stancil on Twitter…well, you’re probably just not on Twitter, which is good for your mental health. But for those who aren’t aware, a liberal social media activist from Minneapolis named Will Stancil got in a giant fight with the entire online left about whether the economy is actually doing well.

Stancil is a big proponent of the “vibecession” theory — the idea that negative perceptions of the economy are due more to negative media narratives than to cold hard economic numbers. The leftists, on the other hand, are pretty committed to saying Biden is a failure as a President, that the economy will always be terrible until we implement Medicare For All and abolish billionaires and so on. Anyway, this has produced some absolutely spectacular battles, since the leftists are numerous and savagely aggressive, but Stancil is utterly relentless and stubborn and has a lot of time on his hands.

Against all odds, Stancil appears to be winning. Where once pessimism prevailed, there has recently been an uptick in positive stories about the economy in major publications like the New York Times and the Washington Post. Consumer sentiment, meanwhile, ticked up this month, as inflation expectations fell:

Even Republicans are feeling a bit less gloomy. And Goldman Sachs’ Twitter Economic Sentiment Index, which may be a leading indicator of overall sentiment, is looking even more positive:

Personally, I feel like this is a vindication for my “Just wait a year” school of thought. There’s econometric evidence that lower inflation takes a while — maybe a couple of years — to seep into people’s consciousness and make them more optimistic. Stancil thinks that media choices drive economic narratives, but I suspect that a lot of it is just the lag between data and popular awareness.

Which means that Stancil was always going to win the debate, because he had the facts on his side, and eventually facts shine through the shouting and B.S. But in any case, as Stancil realizes that the tide has turned in his favor, he has produced a string of absolutely epic tweets. Here are a couple:

As my generation would say, these are pretty metal.

In any case, let’s wait a few more months and see if low inflation continues and economic sentiment continues to improve. I’m feeling pretty optimistic.

3. Interesting facts about U.S. dependence on Chinese imports

In a post last week, I argued that U.S.-China decoupling is slowly but steadily becoming a reality. But if we’re really going to understand decoupling, we need to understand the specifics of how the two economies are “coupled” in the first place. And a recent paper by Richard Baldwin, Rebecca Freeman and Angelos Theodorakopoulos has some very interesting facts about U.S. dependence on Chinese imports.

Importantly, Baldwin et al. look at value-added trade. Remember, what really matters for supply chain dependence is where the value was added, not where the product was shipped from. Knowing this requires data on inputs and outputs, and this takes a long time to gather, so data on value added only comes out with a long lag. Baldwin et al. measure value-added imports (which they call a “look-through” measure), but their data ends in 2018. To be honest, though, I’m not too worried about that, since my rough impression is that 2018 is around when China’s industrial influence reached a peak.

Anyway, the first important fact is about what we buy from China. Americans tend to think of China selling consumer goods to Wal-Mart and such, but this isn’t that important of a story. In fact, China is much more powerful in terms of exporting intermediate goods — parts, materials, and machinery:

China produces around 40% of all the intermediate goods in the entire world! That’s pretty amazing.

And zooming in to the U.S., Baldwin et al. find that China’s importance as a supplier to the U.S. manufacturing sector has skyrocketed in recent decades. In 1995, Japan and Canada were the main sources of U.S. intermediaries for most U.S. industries. By 2018, China was dominant in almost all sectors:

But that being said, the graph above is only about the percent of intermediate goods that U.S. manufacturers import from abroad. In fact, we make most of our inputs ourselves. China only makes about 4.4% of the intermediaries for the U.S. electronics manufacturing industry, 5.1% for vehicle manufacturing, and so on:

What does this all mean? Well, first of all, it means that if the developed democracies want to restore their manufacturing prowess, they need to focus on intermediate goods. And if the U.S. wants to “friend-shore” its supply chains, it should focus on intermediate goods. This means we should use more subsidies and fewer tariffs, since tariffs on intermediate goods are especially harmful to domestic manufacturing (which is a topic for a longer post).

But the fact that U.S. manufacturers don’t actually use that many imported inputs to begin with means that reshoring will probably be a lot easier than the doubters imagine. We’re talking about maybe 3.5% to 5% of inputs here. That’s not a lot, and it won’t be that costly to onshore or friend-shore.

4. How economically important is housing regulation really?

One of the most important economic debates in recent years is over zoning regulation. YIMBYs have focused a lot on upzoning, and have scored some victories, but it’s an open question how much of an economic boost this can actually produce. A famous paper by Chang-Tai Hsieh and Enrico Moretti, published in 2019, claimed that these benefits are extremely large — that if just three major U.S. cities (San Francisco, San Jose, and New York City) hadn’t increased housing restrictions since 1964, the U.S. economy would be 36% larger than it is. That’s a staggeringly high number!

I was always a little skeptical of this paper. It’s a theoretical paper that depends on lots of assumptions — and in economics, that always means it’s subject to a huge amount of uncertainty. The main assumption is that the productivity level of cities is just an inherent characteristic of those cities — that there’s some magical thing about San Francisco that makes workers who live there more productive than workers who live in Cleveland. So under this assumption, simply moving someone from Cleveland to SF would immediately make them as productive as the people who live in SF now. So of course they find huge economic gains — they assume you can just make most of America into San Francisco by literally moving Americans to San Francisco, and that you can just keep doing this and doing this. I doubt this assumption is anywhere close to being true. Clustering effects offer big productivity boosts, but not infinite productivity boosts.

Anyway, Brian Greaney of the University of Washington has a comment on Hsieh & Moretti’s paper that has been attracting lots of attention. Greaney claims that Hsieh & Moretti have major math errors in their paper that result in their estimated effect being about 100x too high. First, he claims to find errors in Hsieh & Moretti’s code. That wouldn’t be too surprising, since others have found some math errors in Hsieh & Moretti’s paper; these errors didn’t end up changing the main result, but they suggest that they weren’t too meticulous about the details. Greaney also claims that Hsieh & Moretti’s result is different depending on what number they use for the total population of the U.S. This is something you do not want a model like this to depend on; you want a result about population distribution to depend only on the fraction of the population that clusters into a city, not on the absolute number of people there.

Hsieh has a response to Greaney, in which he argues that Greaney’s critique about population is misplaced, and that the basic theoretical result doesn’t depend on population size. The reply isn’t really satisfying. First of all, Hsieh claims that Greaney is ignoring general equilibrium effects, but Greaney actually has a simple 2-city version of Hsieh & Moretti’s model in which he shows that the general equilibrium solution leads to the dreaded “unit dependence”. If Greaney has made a math error in this example, it shouldn’t be too hard for Hsieh to find. Second, Hsieh doesn’t even address the coding errors that Greaney claims to find.

That doesn’t mean Greaney is right. But it does show why policy people and commentators shouldn’t put too much weight on Hsieh & Moretti’s result when making arguments for upzoning. The debate is a reminder that the numerical results that everyone waves around — a 36% increase in GDP from upzoning three cities! — are highly dependent on the features of a theory that’s actually a pretty stylized and abstract representation of the real urban economy. And it’s a reminder that even the smartest teams of economists are prone to making small errors that can completely change their results.

Instead of basing all of YIMBYism on one theory paper, it’s good for YIMBYs to make more modest claims about a wider array of outcomes, based on a large number of papers. New research is coming out all the time — for example, I just noticed a cool new paper by Alex Bartik, Arpit Gupta, and Daniel Milo that uses GPT-4 and other AI algorithms to assess the restrictiveness of zoning codes (a promising example of AI doing science that traditional experimental methods struggle with!). In any case, there’s plenty of evidence that housing restriction is bad; even if Hsieh & Moretti (2019) turns out to be fatally flawed, that shouldn’t affect the overall push for upzoning.

5. Immigrants really don’t take U.S. jobs

I believe that Americans are angry about the chaos at the southern border, where a ton of people are trying to spam the U.S. asylum system. And I believe Americans are rightfully worried about some of the local economic harms a wave of asylum-seekers can cause — a major strain on social services in border counties and blue cities, and competition for housing that pushes up rents. For this reason, I think Biden and the GOP should hammer out a bipartisan compromise to reform the asylum system and bring the chaos to an end.

But at the same time, it’s important to remember that many of the common arguments against immigration are just wrong. For example, lots of people think that immigrants push down wages for U.S. workers. I’ve shown lots of evidence that this doesn’t happen. Now here’s some more evidence, from Michael Clemens and Ethan Lewis. They analyze what happens when companies win a lottery that allows them to employ more low-skilled immigrants. The companies increase production, but don’t decrease their hiring of American workers:

The U.S. limits work visas for low-skill jobs outside of agriculture, with a binding quota that firms access via a randomized lottery. We evaluate the marginal impact of the quota on firms entering the 2021 H-2B visa lottery…[Companies who are] authorized to employ more immigrants significantly increase production…with no decrease or an increase in U.S. employment…The results imply very low substitutability of native for foreign labor in the policy-relevant occupations. Forensic analysis suggests similarly low substitutability of black-market labor.

In other words, companies use low-skilled immigrants for one set of jobs, and native-born Americans for another set of jobs, and these jobs don’t really overlap much. That’s why low-skilled immigration really isn’t competition for the native-born. If labor demand for the native-born doesn’t go down at these companies, that means wages aren’t going to fall either, because immigrants aren’t displacing Americans even at the level of the individual companies where they’re hired.

That doesn’t mean immigration is harmless — there are still the housing and social-service aspects to worry about, as I said. But it means that even if you work in an industry with lots of low-skilled immigrants, those immigrants are not going to take your job.

6. A world at war

I keep worrying that the end of Pax Americana will cause war and conflict to increase all over the globe. Well, the latter does appear to be happening. Max Hastings cites some scary data in a recent Bloomberg article:

This week, the International Institute for Strategic Studies in London published the latest edition of its authoritative annual Armed Conflict Survey…It paints a grim picture of rising violence in in many regions…The survey — which addresses regional conflicts rather than the superpower confrontation between China, Russia, the US and its allies — documents 183 conflicts for 2023, the highest number in three decades…The intensity of conflict has risen year on year, with fatalities increasing by 14% and violent events by 28% in the latest survey…

The increasingly assertive policies of authoritarian states — notably China, Russia, Iran, Turkey and the Gulf states — “is one of the main causes of the demise of traditional conflict-resolution and peacemaking processes…These powers often prop up authoritarian regimes and disregard fundamental principles of international humanitarian law.”

Welcome (back) to the jungle. At this point we should be reasonably sure that the breakdown of global order and the rise of authoritarian powers is not a good thing for global peace and stability. The next question should be how the world’s major democracies can assemble a coalition — which may include some authoritarian powers who are willing to break with the others, as it did in WW2 and the Cold War — capable of restoring order. That will be a difficult task, especially due to China’s manufacturing prowess. But that’s what we should be trying to do.

Biden can’t hammer out an agreement on immigration because the GOP doesn’t want an agreement on immigration--they want immigration as an issue in elections. The right will continue to move the goal posts ever further right.

Keep up your 5 Interesting Things. I love it! And the lack of a catchy title or pithy turn of phrase is actually quite refreshing.