At least five interesting things for the middle of your week (#21)

Saudi oil, delayed economic optimism, the EV revolution, U.S. education performance, Indian industrialization, and Chinese urbanism

First, a quick request. I’ve had a couple of people tell me recently that Noahpinion emails are going to their Promotions folder in Gmail. In case this is happening to you, you can make sure you always get Noahpinion emails by clicking and dragging a Noahpinion email to the “Primary” tab in Gmail, like this:

If you do this, Gmail will understand that you don’t want Noahpinion to go to Promotions!

Anyway, on to this week’s podcasts. First we have a new episode of Hexapodia, where Brad DeLong and I discuss the next phase of globalization, and how it’ll look different from the last phase:

Next we have this week’s episode of Econ 102, in which Erik Torenberg and I discuss the nonprofit-industrial complex, AI tutors, and the politicization of science! Here’s a Spotify link:

And here are Apple Podcasts and YouTube, if you prefer.

Anyway, on to this week’s five…er, six interesting things! I’m really falling behind on these, and the list is piling up!

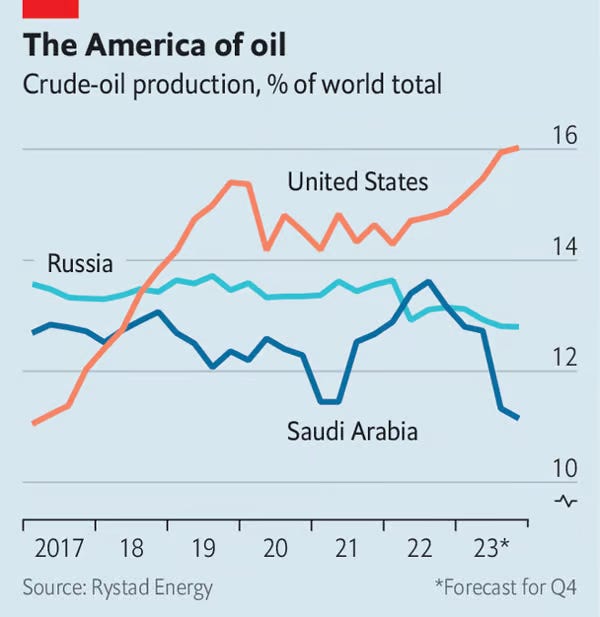

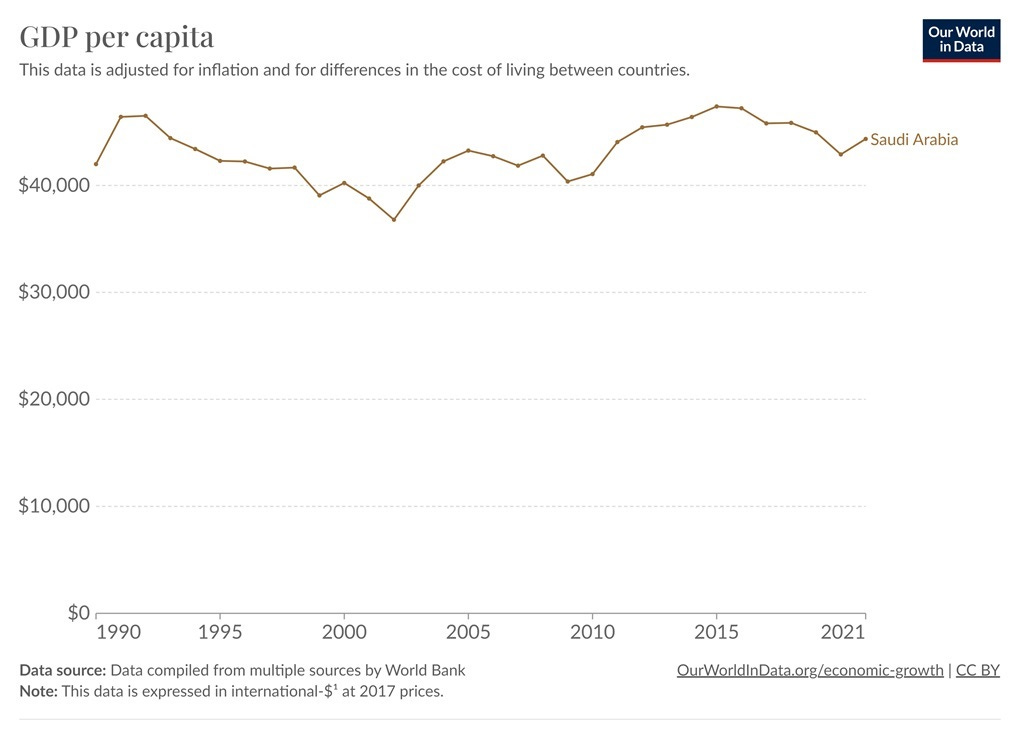

1. Why is Saudi Arabia producing less oil?

Traditionally, people thought that Saudi Arabia was the world’s crucial “swing producer” of oil. The basic idea was that even though Saudi was far from a monopolist in the global oil market, they were the only producer who could increase or decrease production by huge amounts in a very short time frame. And so it was thought that the Saudis could basically control global oil prices, both because global demand is inelastic (meaning that modest swings in production can change prices a lot) and because the other OPEC countries would follow the Saudis’ lead.

But in recent years, another key swing producer has emerged: the United States. Since around 2010, the biggest swing by far has been the rise of U.S. shale oil production. And even as the Saudis have slashed production in 2023, the U.S. has raised its own oil output by almost as much.

And guess which way prices have moved as a result:

The U.S. is winning the tug-of-war. Saudi has cut production, but prices have gone down anyway. The combination of fewer barrels sold and fewer dollars per barrel is dealing a crushing blow to the Saudi economy. The country is now in a recession, with GDP shrinking at a stupendous 4.5% annualized rate in the third quarter.

The Saudis are in big trouble. Their ability to push oil prices around like a monopolist is gone, so cutting production simply impoverishes them. That’s bad news for a country that has seen zero GDP growth in 30 years:

So did the Saudis just make a simple mistake when they cut output? Did they think they were still the swing producer? Or is there some other reason they’re curbing production? Are they even able to maintain production without massively driving up extraction costs? Is it possible that their legendary spare capacity has actually dried up?

If so, that would help explain the country’s eagerness to break into the tech industry. If Saudi oil capacity is weaker than they’re letting on, then diversifying their economy isn’t just a means of resuming growth; it’s necessary to avoid decline.

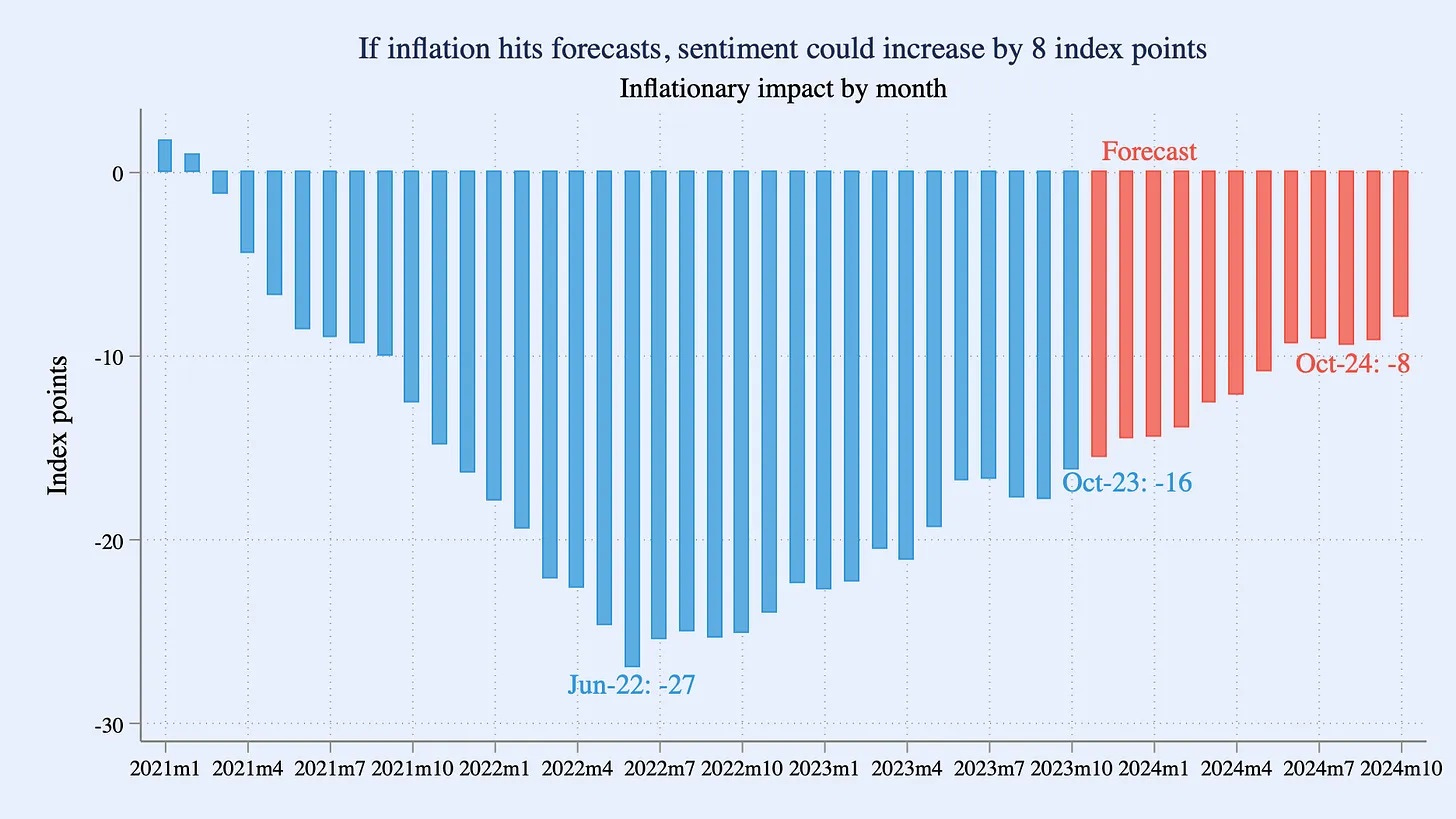

2. Want Americans to be happier about the economy? Maybe just wait a year.

In my post a couple of days ago about “vibes”, I suggested that negative narratives about the economy are causing people to see a lot of data through a distorted, negative lens. And while I think that’s true, I also think that negative sentiment simply responds slowly to improvements in the real economy.

Here’s some evidence for that argument, via economists Ryan Cummings and Neil Mahoney:

Key excerpts:

While prices rose only 3.2 percent this year, they increased by a cumulative 18.6 percent over the last 3 years, and these prior price increases may still be weighing negatively on consumer sentiment.

We…find that the impact [of inflation on consumer sentiment] decays at a rate of about 50 percent per year…If we experience 2.5 percent inflation over the next 12 months, we estimate the cumulative downward drag will drop by another 50 percent.

And here’s the key graph:

This is moderately good news for Biden’s reelection campaign. If inflation fails to spike again, it still won’t quite be “Morning in America” by late 2024, but it’ll be getting there.

In other words, maybe the best answer to the question of why Americans are still so upset about the economy is “Just wait a year and see if they’re still upset.”

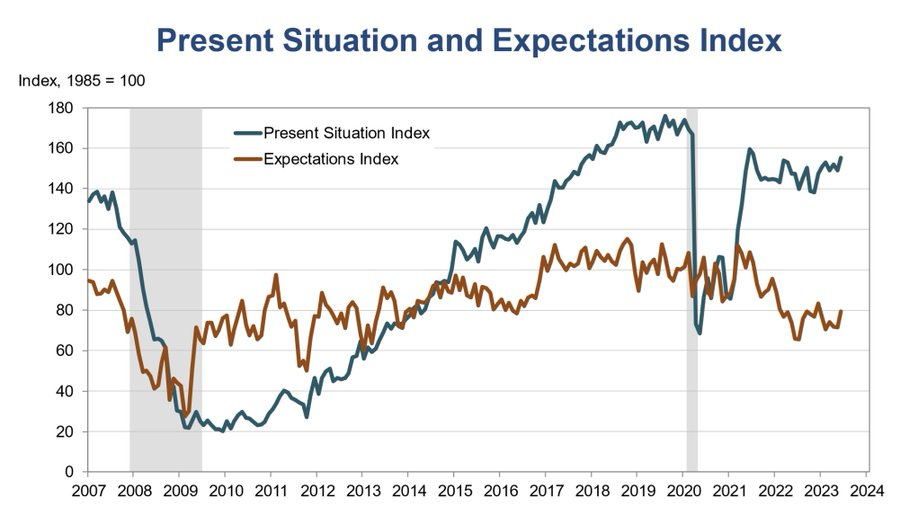

Update: I should have mentioned that a number of economic sentiment indicators are currently rising. For example, here’s a private survey:

And here’s the Conference Board:

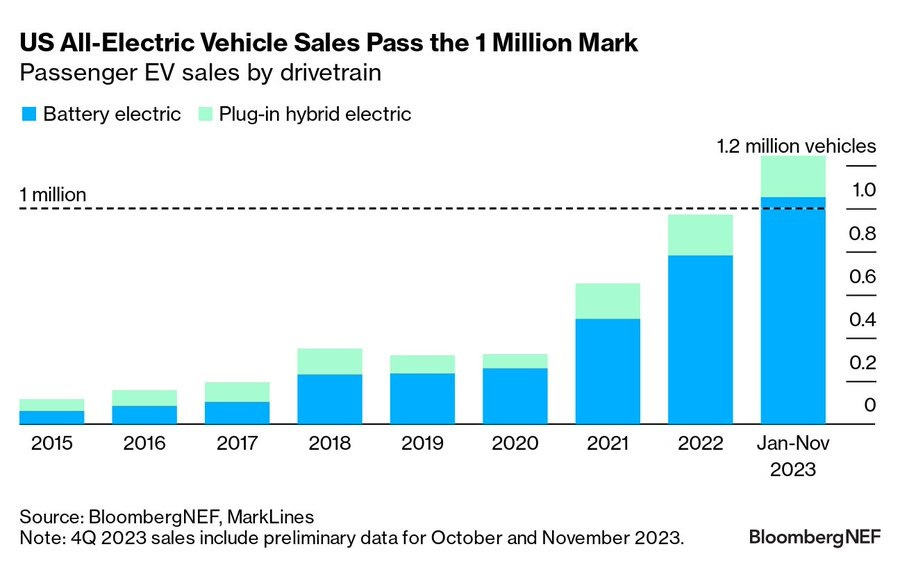

3. The “EV slowdown” narrative is fake

A lot of people claim that the shift to electric vehicles is stalling, at least in America. For example, here’s The Economist from just a week ago, and here’s CNBC from a month ago, here’s Money.com, and so on.

But none of these articles seems to marshal convincing evidence in support of the thesis! The Economist cites a Pew poll showing decreased interest in EVs rather than actual sales, then quickly shifts to comparing the U.S. to China and Europe (where EV adoption has been very rapid). Their graph shows U.S. EV sales still rising! CNBC cites data on how long it takes dealers to sell their inventory of EVs, but given increasing sales, that’s just a sign that dealers got overly optimistic and ordered too many. And the Money.com article compares EV sales to expectations, rather than to the previous year of actual sales.

When you look at actual data, it’s clear that there has actually been no slowdown so far. Americans have already bought more than 200,000 more EVs in 2023 than they did in all of 2022:

I’m sorry, but just because EV sales are less than expected, or less than Europe and China, doesn’t mean the EV transition has “stalled”. It just means that we need to accelerate the transition even more. Yes, it’s worth worrying about the lack of charging stations, and about the fact that some Americans aren’t yet convinced that EVs are the future. But the narrative about the EV revolution “stalling” appears to be a fake trend.

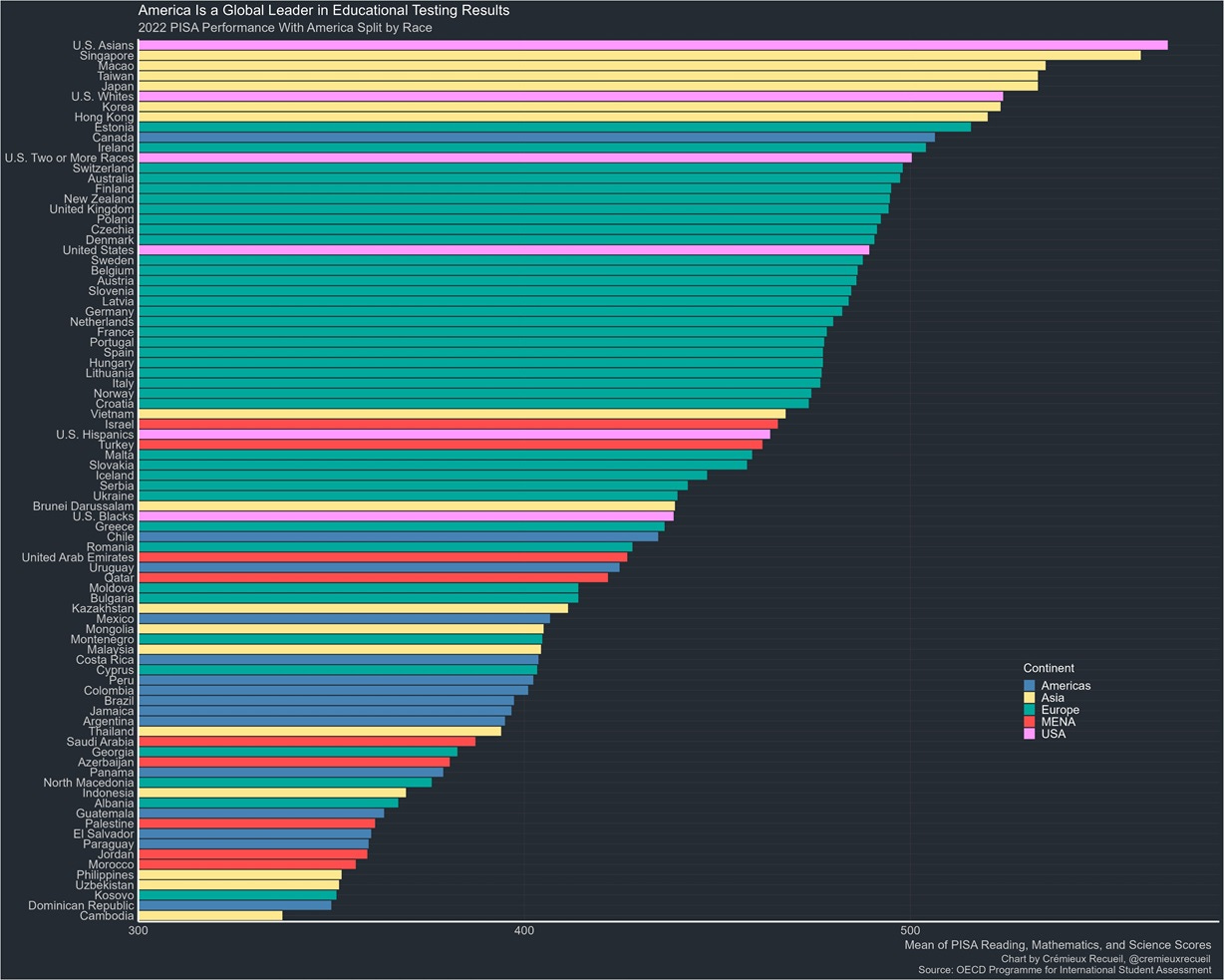

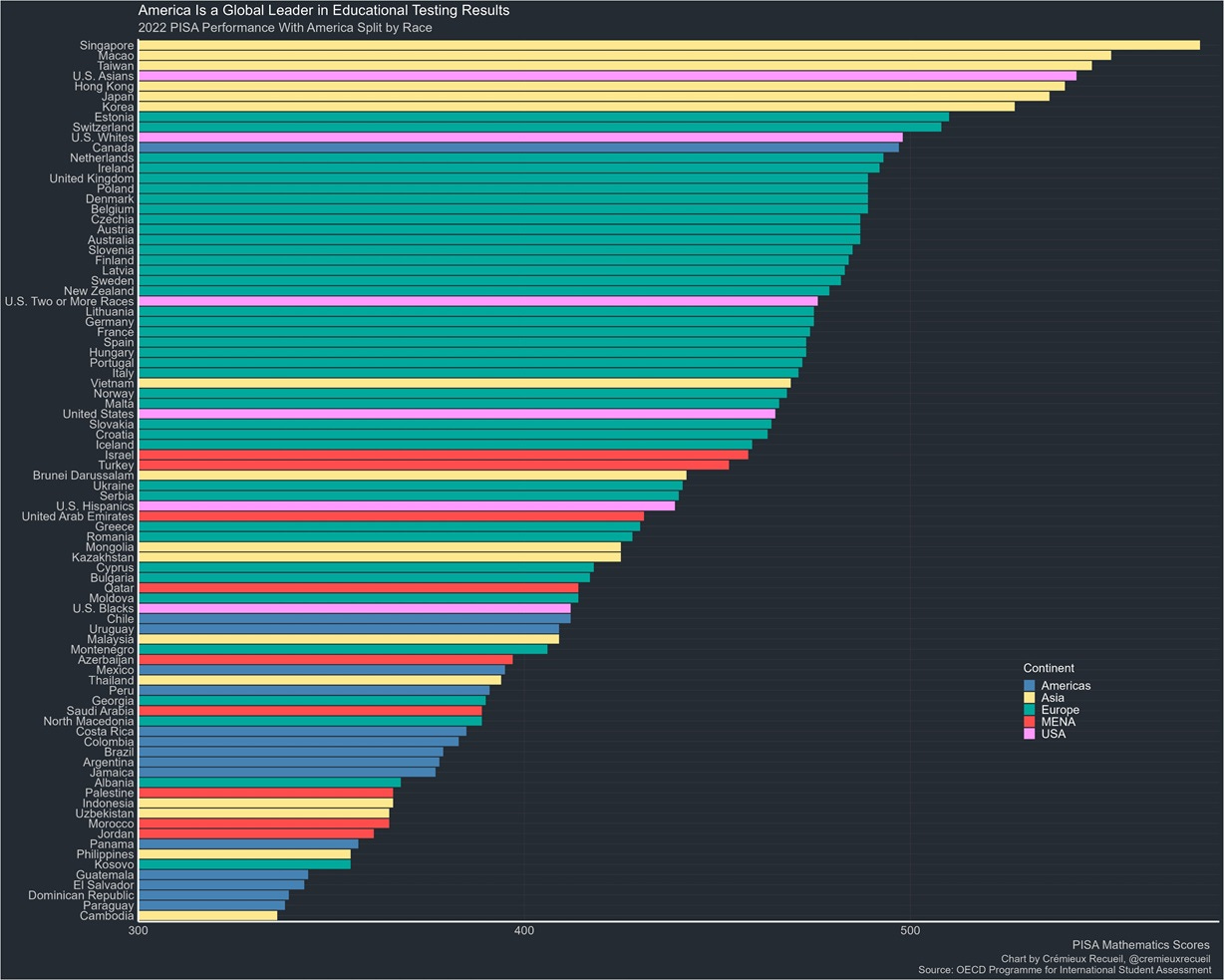

4. American kids are well-educated, except in math

I often complain about the poor quality of math education in the U.S. Math anxiety is pervasive throughout our culture, and we tend to underemphasize the subject. But that said, the overall performance of our education system is not actually that terrible. PISA results are out, and while the U.S. did worse than before — partly as a result of pandemic learning loss — we still come in ahead of the median.

In particular, if you break U.S. PISA results down by race, you can see that although our math education system is highly unequal, it’s not as terrible as you might think. Black American kids outperformed Romanian, Greek, and Bulgarian kids, while Hispanic American kids did better than Slovakian, Icelandic, and Serbian kids:

Meanwhile, White American and Asian American kids came at or near the top.

Note that this does not mean that different racial groups should be judged on separate “tracks”. Instead, what it suggests is that the U.S. education system is capable of delivering great results, for kids with the right resources (including parental preparation). Most of our room for improvement comes from uplifting the kids who are not as well-prepared, so that’s where we should concentrate our resources if we want to move up in these rankings.

Math is still a big problem for the U.S., though. American kids generally excelled in reading and in science. But in math, we lag behind:

Underperformance in math is a function of our education system, which is a function of our values. We treat math as an IQ test — a measure of innate ability — rather than a task that anyone can learn through practice and hard work. But if kids can learn to read and do science, they can learn to do basic math. By deemphasizing math and treating it as a test of inborn ability, we are doing our Black and Hispanic kids a disservice, and disadvantaging our country in the race to build modern high-tech manufacturing industries.

5. On the ground with the next phase of globalization

In my last post, I predicted how manufacturing would spread to India and other developing countries in South and Southeast Asia. Basically, India will start out doing low-value assembly work using imported tools and components, and then gradually work its way up the value chain. Right now, in terms of its position in the supply chain, India is about where China was in the early 2000s.

Viola Zhou and Nilesh Christopher have a wonderful article about what Indian industrialization looks like on the ground. They traveled to a Foxconn factory in southern India, where Apple has shifted some iPhone production in order to diversify out of China. They found that many of the engineers that have been brought over to train and supervise the Indian factory workers are themselves Chinese. Much of their reporting focuses on the interaction and culture clash between the factory’s Chinese and Indian workers.

The story that emerges is a very familiar one. The Chinese supervisors think the Indian workers are slow, lazy and undisciplined — just as the British once thought of German and Japanese workers, when those countries were first industrializing. Industriousness is learned; it proceeds from industrialization. The people who first come to work in the labor-intensive factories are mostly women, looking for independence and an escape from rural life (and probably advantaged by having small fingers). The Indian factory girls are recognizably similar to their Chinese predecessors, or their British forebears centuries ago.

This is the universal tale of industrialization, and it’s a beautiful and terrible one at the same time. It’s a story of ruthless labor exploitation, urban ennui, and harsh working conditions. But it’s also the story of workers escaping what Marx called “the idiocy of rural life”, finding their own way in the world, making money and winning their independence. And it’s the story of a country that is primed to become much richer in the near future.

We know how this story typically ends, too. Indian factories will become more automated; salaries will rise and assembly line jobs will become fewer and more technical. Indians will move into higher-paying service jobs with better conditions. Indian companies will move up the value chain, learning how to make tools and components, eventually creating their own brands and competing with China and the rest of the industrialized world. And then Indian engineers will be off to the next poor country — Bangladesh? Ethiopia? Nigeria? — to start the whole process over again.

I was struck by this paragraph:

Li said Chinese engineers sometimes talked about how they were working to make their own jobs obsolete: One day, Indians might get so good at making iPhones that Apple and other global brands could do without Chinese workers. Three managers said some Chinese employees aren’t willing teachers because they see their Indian colleagues as competition. But Li said that progress was inevitable. “If we didn’t come here, someone else would,” he said. “This is the tide of history. No one will be able to stop it.”

Anyway, if you have the time, go read the whole thing.

6. Some thoughts on Chinese urbanism

Videos of Chinese urban skylines are proliferating across the internet. These often consist of drone photography of skyscrapers, bridges, highways and tourist attractions lit up by LEDs. Here is my personal favorite:

Americans, used to their own shabby infrastructure and dowdy downtowns, often view these videos — or their own trips to these cities — as signs that China is “way ahead” of the West.

And so it may be. But there are a couple important subtleties that tend to get missed when people drool over these glowing skylines.

The first is about China’s style of urbanism. The montages of Chinese cities tend to look very different from montages of other Asian cities like Tokyo or Seoul or Hong Kong or Singapore, where the shots tend to focus on pedestrian spaces. There’s a reason for this; China has generally chosen a different approach to urbanism from other Asian countries. It’s more car-centric, with lots of giant highways and thoroughfares. The retail tends to be clustered in malls or other giant showpiece shopping centers rather than along walkable streets. Residential areas tend to be far from retail and commercial areas, clustered in ultra-high-density “superblocks”. This form of development has sometimes been referred to as “high-density sprawl”.

You can really see this when you look at ground-level videos of Chinese cities. Foot traffic tends to be concentrated in shopping malls or dedicated promenades, while the centers of cities are dominated by huge roads filled with cars. What walkable mixed-use pedestrian-friendly areas do exist tend to be very old, like Shanghai’s Bund and Old City. The skyscrapers and bridges do have plenty of spectacular LEDs on them — LED lighting has become very cheap in recent years — but this is perhaps necessary to break up the imposing, impersonal scale of these cities.

The reason these cities look like they were built for giants instead of people is that…well, they were. The “giants” here are corporations. As Michael Pettis would probably tell you, China over the last three decades has been a producer-centric economy, where the needs of construction companies and developers outweigh the needs of consumers. Giant skyscrapers and highways and concrete promenades and bridges and malls maximized the throughput of Chinese companies, so that’s what got built.

This type of urbanism surely showcases vast production capacity, but that doesn’t mean it necessarily makes Chinese cities amazing places to live, when compared with other Asian cities.

The other thing these videos neglect is capital depreciation. The more you build, the more you have to maintain. In 20 years, these glittering new buildings and infrastructure will begin to show their age; at that point, China’s government will have the choice to spend a lot of GDP upkeeping and rebuilding them (as Japan and Korea do) or letting them start to look a bit shabby, worn, and old on the outside (as Taiwan, Hong Kong, and the United States do).

Depreciation isn’t a mistake on China’s part; every country has to deal with it. But the cycle of new construction followed by depreciation does seem to give a lot of American visitors a very predictably biased impression of whether a country is “rising” or “declining”. In general, a city that looks like the “city of the future” is just one that was recently built.

But anyway, the LED skylines of Chinese cities are still fun, especially when set to some nice music.

Once you get kids reading, all you have to do is to get them to read for pleasure - no / restricted TV / video / screen time. e-screens like the Kindle count as paper. It took a bit to get my son reading, but captain underpants and sponge bob squarepants did it. After that, it was off to the library for him. His mother didn't know that the kindle he had in his bedroom glowed and could be read under the covers.

The deemphasis on math is deliberate. It is also associated with a deliberate deprecation of gifted - talented programs. I believe all in the pursuit of 'equality', in this case by attempting to slow down the learning of more capable and prepared kids. I saw / experienced this 50+ years ago as a student, and I see it repeating for my grandkids. I oversaw my kids education - and when it was insufficient, I supplemented it. They were NOT happy. "Yes, you have to learn how to do it the teacher's way, but you also have to learn to do it dad's way". Mean dad. But a few years later, 'Dad, I don't understand division by polynomials'. "You remember how I taught you long division, we can work it that way." They appreciated my teaching then. I supplemented my daughter's math with correspondence classes in Geometry and Pre-Calculus over the summer before and after 9th grade (she skipped 8th grade).

If you push the math, students can make full use of Running Start / College in High School programs, but at the minimum, they have to be ready for college level calculus in 11th grade. That way they can take the transfer level math classes for STEM majors and transfer to the state university, cutting their college costs roughly in half.

My daughter dropped out of high school after 10th grade and did early admission to the University, where she did her engineering degree. My son did the Running Start path and was able to finish his BS in 7 quarters. He saved himself a lot of money there. They both had their Masters before they turned 22.

"And then Indian engineers will be off to the next poor country — Bangladesh? Ethiopia? Nigeria? — to start the whole process over again."

It will be a great day when manufacturers invade sub-saharan Africa in search of cheap labor. It means their grandchildren will live like South Koreans or Taiwanese.